Visualizing Pareto Fronts

As the name implies, multi-objective optimization problems are a class of problems in which one seeks to optimize over multiple, conflicting objectives.

Optimizing over one objective is relatively easy: given information on traffic, a navigation app can suggest which route it expects to be the fastest. But if you have multiple objectives this problem become complicated: if, for example, you want a reasonably fast route that won’t use too much gas and gives you time to take in the view outside your window.

Or, perhaps, you have multiple deadlines pending and you want to do perfectly on all of them, but you also have limited time and would like to eat and maybe sleep sometime, too. How do you prioritize your time? How do you optimize over all the possible things you could be doing?

This is not easy.

Rather than having a single, optimal solution, these problems have a set of solutions, known as the Pareto front. Each of these solutions is equally optimal mathematically, but each represents a different trade-off in optimization of the features.

Using 3D Rad-Viz, Ibrahim et al. have visualized the complexity of the Pareto front, showing the bumpy landscape these solution spaces have.

Chen et al. take a somewhat different approach – designing a tool to allow a user to interact with the Pareto front, visually seeing the trade-offs each solution implicitly makes and allowing a user to select the solutions they see as best meeting their needs:

prospects for civic media after 2016

Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice is a new book edited by Eric Gordon and Paul Mihailidis. I contributed the introductory chapter, “Democracy in the Digital Age.” On Nov. 16, I joined Eric, Paul, Ethan Zuckerman (MIT), Colin Rhinesmith (Simmons), Beth Coleman (University of Waterloo), and Ceasar McDowell (MIT) for a book-launch discussion that focused on the role of media in the 2016 election and the prospects for civic media in the near future. Here’s the video.

Any Cook Can Govern: Populism and Progressivism

I have lots of feels and lots of arguments about these two pieces by Peter Levine on an alt-left populism:

n a year when we’ve watched a wave of populist elections sweep through the industrialized world on the back of nationalism, Islamophobia, and anti-elitism. Though the left frequently makes populist appeals as well–especially when we’re criticizing agency capture by industry or the undue influence of the very rich–it’s not always obvious to me that progressive political goals are compatible with populism’s mass movements and drive towards uniformity. Progressives tend to be pluralist and cosmopolitan in their egalitarianism.

Is Populism Inherently Nationalist?

For these critics, populist impulses tend towards the violent elimination of difference. Put another way, populist movements tend to become mass movements. Populists appeal to a mythical common good that renders class and geographical interests uniform, and usually identifies an evil or corrupting Other as the people’s enemy. For populism’s critics, the kind of anti-racist and grassroots intellectualism Peter has been describing is something else if it’s possible at all: class solidarity that re-organizes antagonisms without suppressing internal disagreements.

Is Populism Inherently Anti-Intellectual?

Famously, the Progressives of the early 20th Century were quite hostile to the Populists that had gone before. Populist hostility towards elites often swept up intellectuals as well, and the Populists–being farmers–had targeted urban dwellers, financiers, and Jews as their enemies. There is a tendency to lump the rich and the knowledgeable together, so efforts to raise the status of regular working people sometimes try to lower the status of scholars, teachers, and upper-middle class professionals. That’s a worrisome tendency.

But Peter quotes the JCI Scholars Program website, a group I helped found, on our motivations for working with traditionally excluded groups: we do

as collaboration between teachers and students, and to make classes free-ranging discussions and workshops more than lectures.

But is that populist? Even at the JCI Scholars Program, we’re working with the talented tenth: at most 150 students, in a prison that has between 1400 and 1800 prisoners. The main question among prison educators is the extent to which we are engaged in a truly populist project, and the extent to which we are cultivating what Antonio Gramsci called “organic intellectuals.”

My co-founder, Daniel Levine, likes to invoke CLR James’ Every Cook Can Govern on this question. Pulling from Greek sortition, James praised the capacity of ordinary folks to take up the tasks of governance. Of course, this required a much simpler state, and much shorter periods of governance before passing the responsibility on to another. But perhaps our state has become so complex precisely as a result of–and perhaps as justification for–elite domination.

The deeper problem is that sortition required institutional safeguards as well as agreement. And it’s probably relevant that it didn’t survive, suggesting it wasn’t sustainable. As I’ve written elsewhere, Greek sortition depended on a number of institutional factors to function:

The three norms of isonomy are mutually reinforcing: equal participation requires that the office-holder act with the understanding that she might be replaced by any other member of the community. She cannot abuse her office without being held to account at the end of her term. For the same reason she must regularly give reciprocally recognizable justifications for her actions, without which her decisions might be reversed by the next office-holder, or even punished when her office no longer protects her from prosecution. The ideal result of such a regime is a strong preference for deliberation, consensus, and mutual respect, alongside a cautious honesty and transparency with regard to potentially controversial decisions.

really

Populism cannot fall into demagoguery. If facts are relevant to a decision, they must be given proper weight, even if facts cannot be a substitute for values. But though I doubt that populism is inherently anti-intellectual, the problem is that too often our society mistakes credentials for knowledge, which means that anti-elitism requires the motivation of a certain kind of anti-intellectualism.

So that’s the version of populism I can support: one that celebrates the even distribution of insight and institutionalizes a fear of the even distribution of ignorance and arrogance. A populism that is pluralist and cosmopolitan. But I have to admit that this doesn’t really sound much like populism; I usually call it “democracy.”

A Look Back at NCDD 2016 on Storify

With so much that’s happened since October, it’s a little hard to believe that the NCDD 2016 national conference was less than two months ago! Since the gathering, Bridging Our Divides has only become more relevant, and we want to remind our D&D community of the powerful conversations and experiences we had and the commitment we made when we were together.

So we’ve released an awesome Storify page for the NCDD 2016 conference! This compilation of the best photos, quotes from evaluations, links, and other gems from this engaging event will be great for seeing how it was if you missed out, or remembering some of the best moments if you were there.

We encourage you to check out the NCDD 2016 Storify below, and don’t forget that you can always continue the conversation by participating in NCDD’s ongoing #BridgingOurDivides campaign.

Why Some Progress Is Slow for Accessibility

“What’s with that?” a student asked me. Our classroom this semester was on the third floor of Barker Hall at the University of Kentucky. The flights are tall and there is no elevator. “How is that allowed?”

The young woman was asking about accessibility. It’s 2016. Don’t campus buildings have to be accessible?

Before moving to Lexington, I advocated for certain accessibility issues at the University of Mississippi. In the process, I learned a lot about what people say when you push on such issues. There were many disappointing responses at times, the most upsetting of which was being ignored for nearly a year. That’s another story.

Before moving to Lexington, I advocated for certain accessibility issues at the University of Mississippi. In the process, I learned a lot about what people say when you push on such issues. There were many disappointing responses at times, the most upsetting of which was being ignored for nearly a year. That’s another story.

The experience in Mississippi revealed to me some interesting challenges to consider even when an organization means to do its best to make a social space maximally accessible.

If you want to advocate for change, critical thinking textbooks will tell you, you have to understand your opposition and address it head on. Finding the weakest arguments that oppose your mission and laughing at them won’t convince people who disagree with you. Identifying the smartest things people say in their defense and responding to those might.

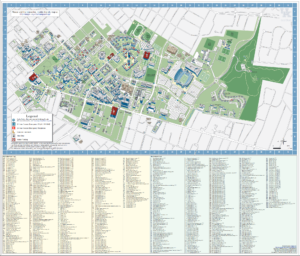

How many buildings are on a university campus? It will vary significantly, but let’s imagine that there are 200 at a major research university. If the campus has been around a long time, many of the buildings will have been built long before the Americans with Disabilities Act. Some will be historic buildings. Others in need of repair. Some will be priorities and others won’t.

How many buildings are on a university campus? It will vary significantly, but let’s imagine that there are 200 at a major research university. If the campus has been around a long time, many of the buildings will have been built long before the Americans with Disabilities Act. Some will be historic buildings. Others in need of repair. Some will be priorities and others won’t.

Classroom space tends to be at a premium in most institutions. When all of the most commonly used spaces have been taken up, you look for further spots not yet in use. My courses were added far later than is usual this past summer, so they were located in classroom space still available. It so happens that that means Barker Hall.

Barker Hall is historic, built in 1901. The first photo of it is how it looks now, although it is actually surrounded by construction of the new student center at present. The next photo showcases what we mean when we call it historic.

Barker Hall is historic, built in 1901. The first photo of it is how it looks now, although it is actually surrounded by construction of the new student center at present. The next photo showcases what we mean when we call it historic.

So why isn’t it accessible?

- Making spaces accessible as you build them is cheaper than retroactively. So, it’s more expensive than making other, perhaps more spacious new buildings accessible.

Making historic buildings accessible generally adds cost, because it is desirable to preserve the beauty of historic buildings, while retrofitting. It’s harder, so it costs more.

Making historic buildings accessible generally adds cost, because it is desirable to preserve the beauty of historic buildings, while retrofitting. It’s harder, so it costs more.- It probably is not the only remaining space that needs retrofitting.

- Money is always limited and judgments are made all-things-considered about where to spend it.

- Without many people calling for Barker to change, it won’t any time soon. Though, there may be plans in the works to update it at some point.

But wait, “Isn’t it the law?!”

- No, it’s not technically the law that every space has to be accessible to every person. The law says that institutions like mine have an obligation to make reasonable accommodations for people who need them. That means that if any of us had a broken ankle or if a student who uses a mobility device were to have added the course, the university would have had to find some solution to move the class meetings.

This last point is delicate, though. How would it make you feel if 30 other people had a change to their meeting location for a semester because of you? It’s something that couldn’t help but make someone feel singled out. Maybe the first classroom was conveniently located for certain people. Barker Hall is a hop away from Patterson Office Tower, where my office is. So, in the end, this answer is not terribly satisfying.

My point here is not that I think it’s fine to have inaccessible buildings. Hell, the window unit air conditioners made it hard to hear each other in August, a problem for people with hearing impairments, not to mention anyone trying to engage in a classroom discussion.

No, this professional baseball team executive has nothing to do with the story here, except that he’s struggling to hear someone, as I often did this semester.

So, at some point I’ll gently start to ask questions about what the structure is here for decisions and initiatives regarding accessibility. It was refreshing, I must say, to hear disdain in the student’s voice. I heard passion and initiative in it. You can’t change much for the better without high expectations. At the same time, the challenges are real even when good people are trying to do many things right with limited resources.

Next semester, I’ll be teaching on the second floor of a building with several elevators. And central air.

Follow me on Twitter @EricTWeber and on Facebook @EricThomasWeberAuthor.

separating populism from anti-intellectualism

I’m a populist, yet I advocate the life of the mind. I’d like to see less elitism (of certain kinds) along with more intense and widespread intellectual inquiry. Unfortunately, the most prominent varieties of populism today are anti-intellectual. This is a problem rooted in social structures. Some of the solutions involve changing the way formal educational institutions work. Others involve enhancing intellectual life in informal contexts.

Let’s define “anti-intellectualism” as a rejection of advanced, specialized, complicated thought, which is viewed as antithetical to common sense. According to Mark Fisher (The Washington Post 7/17), Donald Trump is an explicit anti-intellectual:

He said in a series of interviews that he does not need to read extensively because he reaches the right decisions “with very little knowledge other than the knowledge I [already] had, plus the words ‘common sense,’ because I have a lot of common sense and I have a lot of business ability.” Trump said he is skeptical of experts because “they can’t see the forest for the trees.” He believes that when he makes decisions, people see that he instinctively knows the right thing to do: “A lot of people said, ‘Man, he was more accurate than guys who have studied it all the time.'” … Trump said reading long documents is a waste of time because he absorbs the gist of an issue very quickly. “I’m a very efficient guy,” he said. “Now, I could also do it verbally, which is fine. I’d always rather have — I want it short. There’s no reason to do hundreds of pages because I know exactly what it is.”

Presumably, Trump’s anti-intellectualism was more of a political asset than a liability in the campaign, and that tells us something about our culture. (On the other hand, one of the most curious and thoughtful political leaders in modern America–and a very fine writer–won the two previous presidential elections, so politics is not a vast wasteland.)

Let’s define “anti-elitism” as a rejection of the superior position, entitlement, and power of some privileged group. This is different from anti-intellectualism because an elite needn’t be defined by knowledge or expertise: the business class, for instance, usually is not. However, the two ideas often come together, not only in Trump’s rhetoric but in many other examples from American history. For instance, in Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963), Richard Hofstadter wrote:

The kind of anti-intellectualism expressed in official circles during the 1950’s was mainly the traditional businessman’s suspicion of experts working in any area outside his control, whether in scientific laboratories, universities, or diplomatic corps. Far more acute and sweeping was the hostility to intellectuals expressed on the far-right wing, a categorical folkish dislike of the educated classes and of any thing respectable, established, pedigreed, or cultivated. The right-wing crusade of the 1950’s was full of heated rhetoric about “Harvard professors, twisted-thinking intellectuals … in the State Department; those who are “burdened with Phi Beta Kappa keys and academic honors” but not “equally loaded with honesty and common sense”; “the American respectables, the socially pedigreed, the culturally acceptable, the certified gentlemen and scholars of the day, dripping with college degrees .. . the “best people” who were for Alger Hiss”; “the pompous diplomat in striped pants with phony British accent”; those who try to fight Communism “with kid gloves in perfumed drawing rooms “; Easterners who “insult the people of the great Midwest and West, the heart of America; those who can “trace their ancestry back to the eighteenth century or even further” but whose loyalty is still not above suspicion; those who understand “the Groton vocabulary of the Hiss-Achcson group.”

The businessmen who distrusted independent intellectuals represented one elite quarreling with a different one–Wall Street and Detroit struggled for influence with the Ivy League and the State Department. But the “far right-wing” rejected elites that they defined in terms of social privilege rather than intellectualism. For these people, the problem with Groton School alumni was not their sophisticated ways of thought but their social pedigree and arrogance. These right populists were against Wall Street and Harvard. Although Hafstadter is writing here about the right wing, some left populists share the same targets.

I think anti-elitism and anti-intellectualism come together because educational institutions serve two functions simultaneously.

On one hand, schools and colleges are spaces for intellectual inquiry. They are the most prominent and best supported places where people address unanswered questions of public importance, conduct deep and sustained conversations about unresolved topics, and model and teach the skills and values required for those pursuits.

At the same time, schools and colleges confer social status. A college degree is a prerequisite for occupying many of the advantaged slots in our social order. Educational institutions at all levels teach not only intellectual skills, but also manners, modes of social interaction, and ways of writing and speaking that mark out the advantaged class. And despite their protestations that they admit students fairly, they are dominated by children of privileged groups. For reasons that I’ve explored in some length, I don’t think this situation is likely to change markedly.

To make matters even more fraught, the genuine search for knowledge can be conducted arrogantly or else responsively. One can pursue the truth by studying other people and their problems in order to change those people (for good or ill), or one can listen and create knowledge together. Finally, claims to advanced knowledge can be trustworthy or not. After all, highly credentialed experts are the ones who told us to blast highways through inner cities, minimize fat consumption, and invade Iraq.

I think several trends worsen the conflation of populism with anti-intellectualism today.

First, although advanced intellectual inquiry occurs in some spaces that aren’t educational institutions–community organizing groups, online magazines, some religious communities, and hip hop–the state of “informal” intellectual life does not seem to be strong today compared to the past. Most of the people who can spend a lot of their time reading, writing, and talking about complex issues work as teachers or professors.

Second, tools for data collection, analysis, and influence are giving frightening amounts of power to people who possess and deploy information.

Third, in a post-industrial economy, the workforce is increasingly divided between people who work with their hands in low-status roles, and others who work with symbols and data. The former understandably wonder why they must pay for the latter, whether directly or via taxation. University of Wisconsin professor Kathy Cramer describes how she would visit small towns in her state and introduce herself “as a public opinion scholar from the state’s flagship university.” When she asked citizens what concerned them most, they often “expressed a deeply felt sense of not getting their ‘fair share’ …. They felt that they didn’t get a reasonable proportion of decision-making power, believing that the key decisions were made in the major metro areas of Madison [where Kathy works] and Milwaukee, then decreed out to the rest of the state, with little listening being done to people like them.” It became clear to Cramer that when they complained about people who didn’t work hard enough, they were “talking about the laziness of desk-job white professionals like me.” Why did their tax dollars have to pay for someone to drive around the state asking people political questions so she could write her books?

Finally, today seems like a time of growing deference to high-status people. As I wrote last fall:

We live at a time when billionaires, celebrities, and CEOs are given extraordinary deference, especially in comparison to run-of-the-mill elected officials, civil servants, union leaders, and grassroots organizers. Politicians, for instance, are constantly in contact with their wealthiest constituents. First-year Democratic Members of the House are advised to spend four hours per day of every day calling donors. Meanwhile, many advocacy groups are funded by rich individuals, not sustained by membership dues, so their leaders are also constantly on the phone or at conferences and meetings with wealthy people.

One solution is to identify, strengthen, and lift up informal spaces where people who haven’t attended college–at least, not recently–engage in intense intellectual work. When I interviewed the great community organizer Ernesto Cortés, Jr. (Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) co-chair and executive director of the West / Southwest IAF regional network), he told me this was his organization’s strategy:

Building talented, committed, enterprising relational organizers through recruitment, training, and mentoring. We develop their capacity to be reciprocal, relational organizers. Ask–what do Aristotle and Aquinas say? Explore the different traditions. Offer all kinds of seminars with a wide range of scholars from left, right, center. Develop their intellectual capacity, which is the capacity to be deliberative. Help them to understand labor, capitalism, the various faith traditions, strategic thinking. We offer what amount to postgraduate-level seminars in how to create effective leaders in an institutional context–not lone celebrity activists–people who build institutions that can then be networked together. …

Another example is the impressive array of liberal arts programs now being taught in prisons on a pro bono basis by professors. For instance, the Jessup Correctional Institution Scholars Program explains:

Our Program is dedicated to a simple concept: no one in society should be deprived of access to ideas. This has led all of us, through different paths, to seek opportunities to teach and learn outside the walls of the academy, built to keep people out on the basis of their social standing and financial means. And it has ultimately led us to bring intellectual discussion inside the walls of the prison, a space that too many people consider radically separate from society. We see society as a whole riddled with locked doors and those of the prison are just one more set that we hope to open.

Everyone in the program is a scholar, and we think of ourselves as on equal moral and intellectual footing – we strive to create course content as a collaboration between teachers and students, and to make classes free-ranging discussions and workshops more than lectures.

Another solution is to do the intellectual work of the university in ways that better engage laypeople. Guided in part by Albert Dzur, I argue that the way to accomplish this is not to teach graduate students and PhD researchers to be more modest and humble. That message never sticks with an ambitious group, and it’s not really the ideal, anyway. We actually need more courageous and enterprising research. Instead, we can recognize that engaging members of the public in creating and using knowledge requires highly advanced skills–it’s a form of democratic professionalism. We should teach, evaluate, and reward excellent democratic professionalism in the academy.

A third solution is for the academy to take more responsibility–at the institutional level–for communicating research and intellectual life. It used to make some sense to assume that academics conducted research and professional reporters selected and translated the most relevant findings for their readers or listeners via mass media. If that model ever worked, it doesn’t work now that 30% fewer people are employed as professional reporters. Just as institutions of higher education created public broadcasting, so they must now launch new forms of communication.

None of these three strategies will solve the underlying problem completely. The social underpinnings are problematic and require reform. Meanwhile, there are tempting political payoffs for politicians who demonize intellectual life. But these are three ways of fighting back.

Engaging Ideas – 12/9

Call for Deliberative Campus Forums on Abortion

We want to encourage our higher ed members to take notice of the announcement below from Dr. Robert Cavalier of the CMU Program for Deliberative Democracy, an NCDD member organization. The PDD has been testing and refining a set of resources for deliberative forums on abortion, and is inviting others to join them in hosting such forums on their respective campuses this Spring. You can learn more about the project in Robert’s announcement below or learn more about their resources here.

Announcement for Campus Conversations on the Issue of Abortion

Over the past several years the Program for Deliberative Democracy has been developing ways for citizens to have a civil and constructive conversation on the issue of abortion in America. We are pleased to say that we have put these materials online for use by campuses across the country. I am writing to you today because your organization has worked in the field of deliberative democracy and is well placed to announce this opportunity to your community.

Over the past several years the Program for Deliberative Democracy has been developing ways for citizens to have a civil and constructive conversation on the issue of abortion in America. We are pleased to say that we have put these materials online for use by campuses across the country. I am writing to you today because your organization has worked in the field of deliberative democracy and is well placed to announce this opportunity to your community.

Our materials dealing with the issue of abortion are designed to be used in a campus discussion that follows the general protocols of deliberation (well vetted background material, trained moderators, expert panels, and pre- and post-event surveys). As with our other materials (such as “Climate Change and the Campus”), the college discussions on abortion will also focus on specific campus issues i.e., reproductive services.

Please use the following announcement for dissemination purposes:

Beyond the Picket Lines: A Campus Conversation on the Issue of Abortion, Clinic Regulations and Campus Reproductive Resources

Forty years after the Supreme Court Decision on Roe v. Wade, the political debate over the issue of abortion continues. The most recent arguments before the Supreme Court, in the case of “Whole Woman’s Health et al. v. Hellerstedt,” have provided yet another way to look at and to discuss the topic.

The Program for Deliberative Democracy is releasing materials that will enable campuses across the country to run their own versions of a Deliberative Forum. Guidelines materials for hosting these events are available at http://hss.cmu.edu/pdd/iaia. At the host sites, the sampled individuals will gather in small, moderated groups to discuss the topic. They’ll formulate questions to be asked during a plenary session with experts and then gather once again to respond to a post-survey.

The data drawn from these surveys will have ‘consulting power’ and could be used by stakeholders to influence concrete campus policy, including feedback on campus reproductive services.

Our experience in developing these kinds of events convinces us that we can not only address this issue in a civil and constructive manner, but that the very process of informed, well structured conversations itself demonstrates the advantages of a more deliberative, less divisive democracy.

In our beta tests over the past 2 years, the survey results on campus reproductive services policy have been found most useful. We hope that you will find a use for this important discussion on your campus this Fall or next Spring.

For further information and free consultation, please contact Dr. Robert Cavalier at rc2z@andrew.cmu.edu. Please join us in this important project.

More background on the project in the video below: