This Democracy Works podcast from Penn State’s McCourtney Institute for Democracy is a conversation between me and Chris Beem about my 2022 book What Should Do? A Theory of Civic Life. I enjoyed our discussion!

Monthly Archives: February 2023

sabbatical update

I’m in Granada, Spain, for three months, as part of a sabbatical. We’re living in a “carmen,” which is a “a type of urban housing” typical of two specific neighborhoods in this city, “with an attached green space, both garden and orchard, that constitutes an extension of the dwelling, according to the classic definition of Seco de Lucena. A Carmen is a space closed to the outside, surrounded by walls about two meters high, usually whitewashed, with lush vegetation” (per Wikipedia).

That describes our rented house quite well. We’re located near the summit of the Albaicin, the neighborhood of which the young Lorca wrote, “[El] tiene sonidos vagos y apasionados y esta’ envuelto en oropeles suaves de luz oscura” (“It harbors vague and passionate sounds and is wrapped in soft tinsels of dark light”). I see what he meant, but the views are usually crisp and vivid–with the snow-capped Sierra Nevada rising behind the sharp angles of the Alhambra–and the birds that provide most of the soundscape seem raucously cheerful rather than wistful for the lost world of al-Andalus.

I’m busy with several research projects that will benefit from concentration, including an interesting collaborative study that involves trying to diagram the logic of open-ended responses to a political survey. I appreciate the quiet hours when Americans are asleep, although I’m glad to hear from people once dawn breaks in the USA.

Although I’m certainly learning about Granada and Spain, I feel too much of a novice to post much about those topics yet. I presume I will blog normally about civic engagement and related matters.

politics without metaphysics?

During three recent talks on What Should We Do? A Theory of Civic Life, I received interesting questions of a similar type.

In the book, I argue that human beings must come together in a whole variety of groups in order to learn what is right by discussing and acting together. I claim that this is our best way of pursuing wisdom.

The questions I received were about animals and/or the divine. Does my account presume that people are the only beings that fully count? That assumption could be cashed out as a metaphysical view–for instance, that human beings alone have free will and therefore represent the sole intrinsic goods. As such, it would conflict with many other metaphysical views–for instance, that all sentient beings have been given harmonious roles by their attentive creator.

My answer (hardly an original one) is fundamentally pragmatic. I think that discussing and acting with other human beings is the best way we have to make ourselves wise. We don’t have the option of including animals in our discussions because they can’t talk. And we don’t get direct and explicit divine instructions, unless perhaps very rarely.

This does not mean that animals don’t count or that there is no higher power. Perhaps we have very important duties toward other sentient creatures (which may require close attention to their expressed needs) and toward God or gods. But we must define and honor these duties by interacting with other human beings.

John Rawls is the most famous advocate of the idea that politics does not require metaphysics (see “Justice as Fairness: Political not Metaphysical,” 1985). I am saying something similar, except that my view is much more polycentric.

The main focus of Rawls’ thought is a constitutional democracy as the sovereign power in a nation. He sees a legitimate government as the mechanism for deciding what justice demands. Because its citizens have the right to hold their own religious and other fundamental views, a legitimate state must be neutral in relevant ways, which makes it “liberal” in a certain sense of that term.

I view any religious denomination as one of the venues in which people come together to decide what is right to do together and to learn from one another. It may be defined by certain metaphysical premises that all its members endorse (although that is not uniformly true of religions). Unlike Rawls, I do not see the liberal state as one uniquely legitimate umbrella organization set over the religious denominations and other groups. Rather, a society is a panoply of associations that have diverse purposes and assumptions, and the liberal state is simply the association that is charged with settling a range of issues that involve public law. The society as a whole generates wisdom (and folly, in various proportions).

Most of our associations have no need to be neutral about metaphysics. They are entitled to take strong positions about the divine, about nature, and about other philosophical questions. Still, all of them are necessarily groups of human beings, and the topic that interests me is how to design them to bring out the best in their members. That topic does not seem to require getting the metaphysics right.

Objection: When some groups of human beings gather to decide what they should do, they consult non-human sources. They pray, they study texts of revelation, or they commune with nature and try to learn from non-human animals. Must we not decide whether their beliefs are correct in order to assess their behavior? For instance, perhaps it is wise to pray to a divinity that exists but not otherwise. In that case, metaphysics must come before politics.

I would answer this objection from two different perspectives. First, as an individual, I must put myself in groups to learn from others and keep myself accountable to them. To some extent, I can choose which groups to join. Their core philosophical commitments are relevant to my decisions about membership. I should be less likely to join a group that I fundamentally disagree with, and some of those wouldn’t want me in the first place. However, core philosophical commitments represent one kind of consideration among others. Plenty of people are good members of religious communities despite doubts. In short, I can critically assess groups and join only my favorite ones, but I shouldn’t be too fastidious about these choices.

Second, as a citizen, I should be glad that there are many different groups. They reflect freedom of association and diversity. They contribute to the society-wide discussion. Not only should I fight for their First Amendment rights and tolerate their presence, but in many cases, I should actively learn from them. Even if I disagree with their metaphysics, they may have insights that would benefit me. From a different perspective: even if I am foolish in doubting their articles of faith, their divine inspiration can speak to me through their human members.

I often return to John Dewey’s formulation of “the democratic idea in its generic social sense” from The Public and Its Problems (1927). He proposes three principles. Everyone should belong to many groups, which must “interact flexibly and fully” with each other. These groups should derive the full benefit of all their members’ contributions. And people should be involved in “forming and directing the activities of the groups” to which they belong. This vision is all about human beings, but I don’t think it challenges either religious beliefs or deep concerns for nature. It is rather an idealistic account of how people–who may hold diverse fundamental views–should govern ourselves, because that is something we must do.

See also: modus vivendi theory; bootstrapping value commitments; what if people’s political opinions are very heterogeneous?; social justice from the citizen’s perspective; what secular people can get out of theology; the I and the we: civic insights from Christian theology; latest thoughts on animal rights and welfare, etc.

a Ukraine War timeline

I have no expertise or personal experience in military affairs and a shallow knowledge of Eastern Europe, but I have been following the Ukraine war avidly on a daily basis. This summary might have some value for those who are following matters less closely than I–as long as you remember the caveats about my amateurishness.

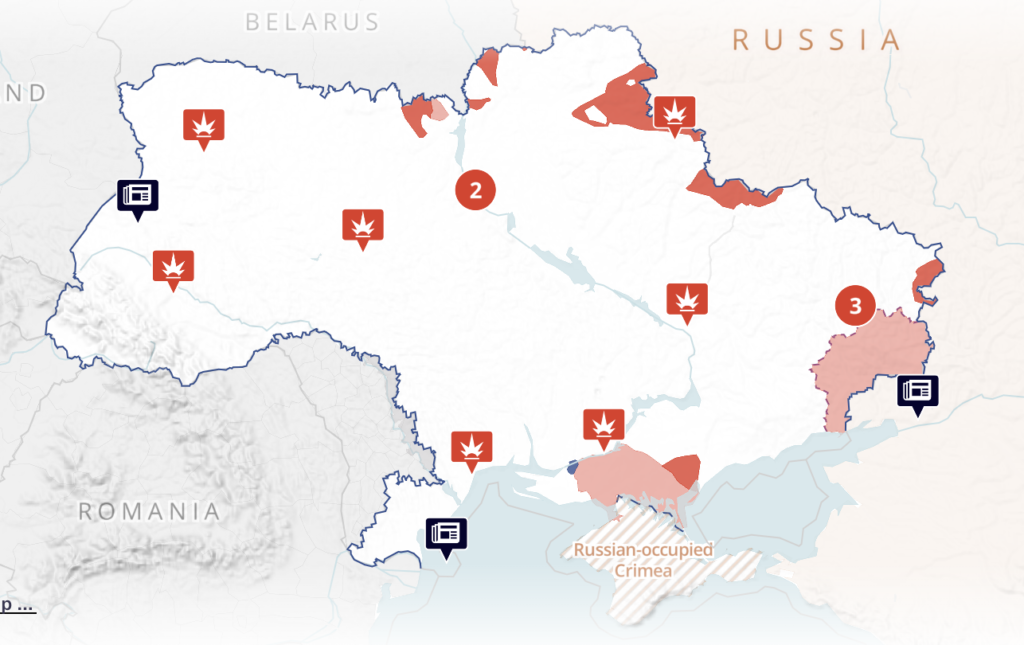

I illustrate this timeline with maps from the Neue Zuericher Zeitung (the Swiss newspaper), because they work well graphically. The NZZ helpfully explains how and why their maps differ from some other credible ones.

Russia’s armed conflict with Ukraine begins in 2014. By February 24, 2022, Russia and its proxies occupy substantial (but disconnected) portions of Ukraine. The current war begins with strikes against military targets, denoted with the icons of explosions below.

Putin probably thinks that he is sending about 200,000 well-equipped soldiers into Ukraine under officers who have gained combat experience in Syria and elsewhere. He probably assumes that the Ukrainian government is almost a joke: unpopular, corrupt, propped up by the CIA, and led by a comedian. He orders an ambitious attack on multiple fronts and expects the conflict to conclude in days.

That multi-front offensive has culminated by mid-March, with massive Russian casualties and atrocities against civilians, especially on the route south from Belarus. It is becoming clear that the Russian force was hollow, due to corruption and falsified reporting up the line, whereas the Ukrainians are motivated and prepared. Russian occupied territory teaches its maximum extent around March 15.

By April, the Russian columns in the north and northeast have withdrawn in defeat, and the focus is a bloody battle to control a devastated port city of Mariupol in the southeast. The Russian offensive is now very slow, but Russia controls a continuous band of Ukraine that includes much of Ukraine’s industrial east and its seacoast and ports.

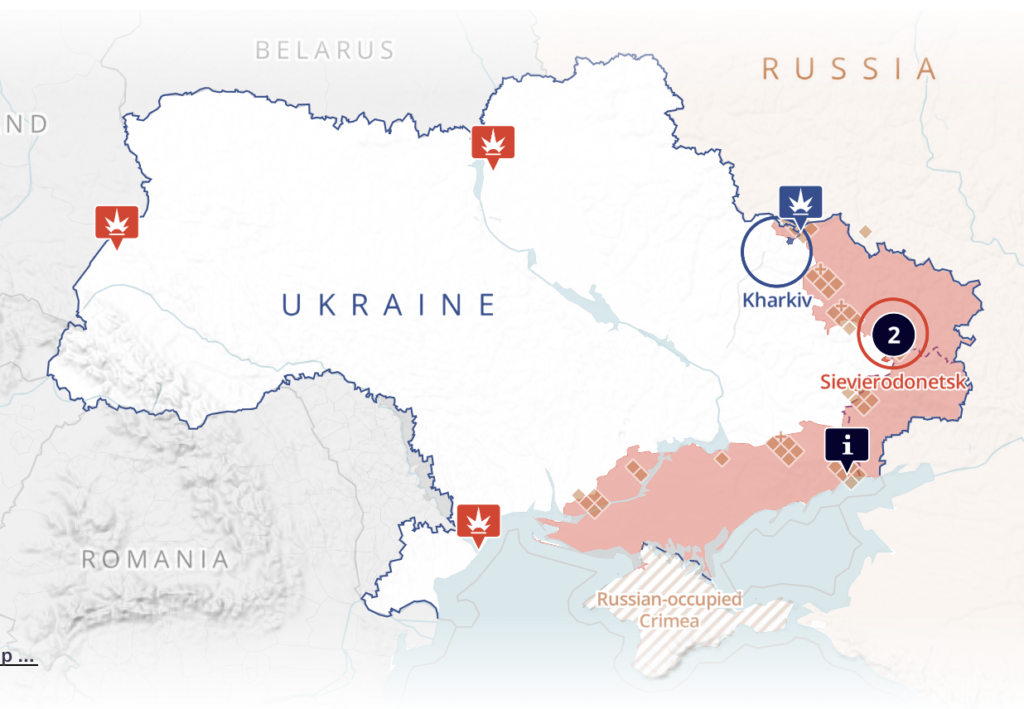

Mariupol falls by early May. Ukraine’s second city, Kharkhiv in the northeast, is close to the front and constantly bombarded. The next phase is a slow Russian advance in the the eastern zone, enabled by massive artillery support. Major fighting centers on the cities of Sievierodonetsk and Lysychansk, which have little military value, according to independent military experts. Still, Russia wants to claim that it retains offensive goals. (On April 14, Ukraine sinks the Russian battleship Moskva, an episode in the ongoing naval campaign.)

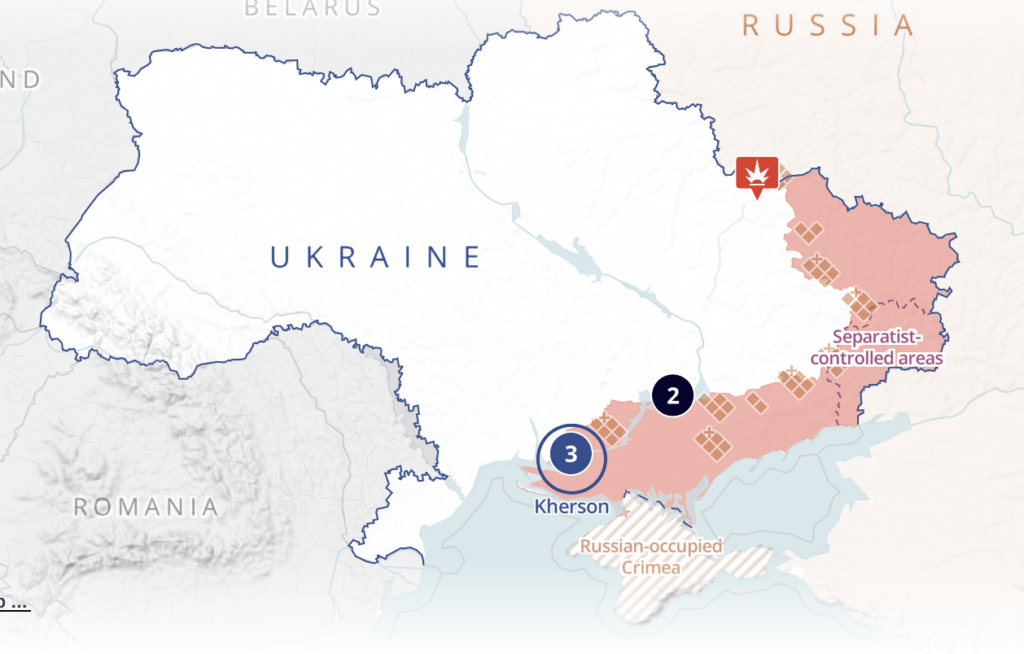

The map in late August looks similar, because Russian forward movement has essentially stalled. At this point, Ukraine is sending all kinds of signals that it will counterattack along the southern tier, targeting the city of Kherson on the right (western) bank of the Dnipro River. By this time, it is possible that Russia is already planning an organized retreat from Kherson, which is difficult to defend because of the wide river.

The southern counteroffensive was a feint. Ukraine manages a rapid surprise advance in the north and then down into the north-center, while Russia withdraws from Kherson anyway (with light losses, in one of Russia’s under-recognized successes). Ukraine regains Kherson, Izium, Lyman, and other cities and territory.

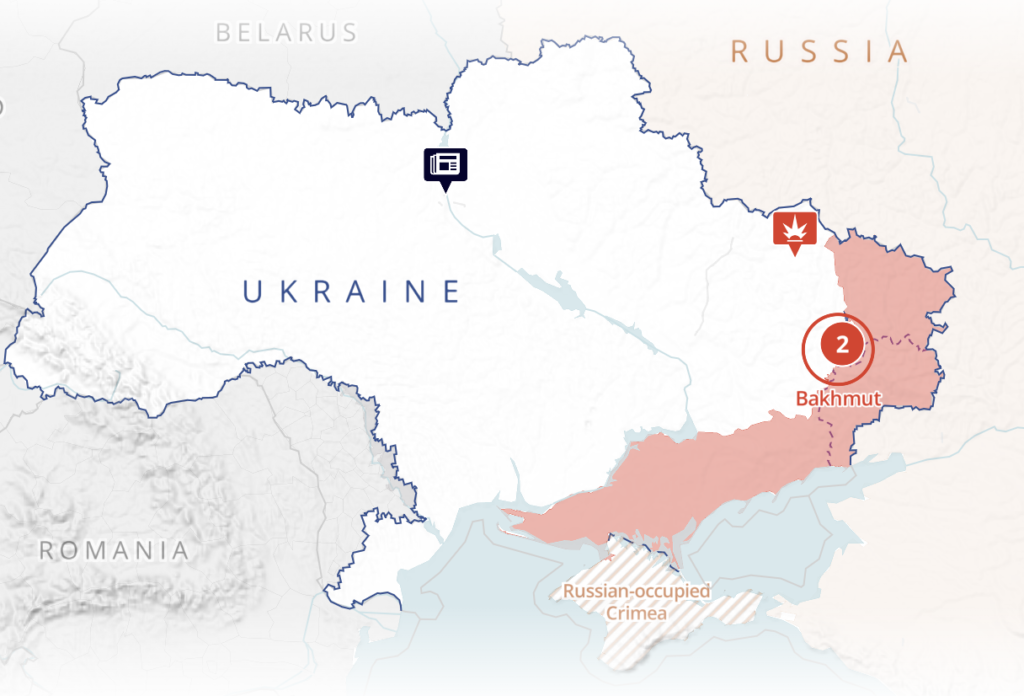

As the Ukrainian counteroffensive culminates, attention turns to the small city of Bakhmut, which both sides seem eager to award symbolic significance. For the Ukrainians, the goal may be to entice Russians into a Pyrrhic campaign for a target of little strategic importance. In any case, the map for Jan. 10, 2023 (below) looks very similar to that for late August (above). But these maps do not depict the constant strikes against Ukrainian civilian targets as far west as Lviv–or the Ukrainian attack on the Kerch Bridge, a vital Russian supply route, on Oct. 8.

During this period, it is likely that Russia is focused on mobilizing, training, and equipping a new cohort of 300,000 reservists and redirecting its heavy industry for prolonged war. Putin may have no short-term offensive hopes between August and January, and you’d have to squint to see the differences between these maps.

But acknowledging that the Russian offensive has stalled would embarrass Putin politically and could embolden Ukraine’s allies. Therefore, the Kremlin encourages irregular proxies to continue fighting, especially for Bakhmut. These proxies include the “People’s Militia of the Donetsk People’s Republic,” “the People’s Militia of the Luhansk People’s Republic,” Chechen forces under Ramzan Kadyrov, and especially the “Wagner Private Military Company” under billionaire Yevgeny Prigozhin, which recruits/pressgangs Russian prisoners as troops. Political ambitious motivate these groups to continue fighting (and quarreling amongst themselves), even when the costs are extraordinarily high. They serve the Kremlin’s propaganda needs and cause Ukrainians to die, while Russia strives to restore its regular Ministry of Defense forces. By today, Prigozhin has probably outlasted his welcome and is being marginalized. I would not be surprised to see him in jail soon.

The UK Ministry of Defense and Institute for the Study of War both believe that an attempted Russian advance–using its reconstituted, regular forces–began in mid- to late-January, 2023. This offensive was not announced, probably because of anxiety about whether it would succeed. The fog of war is thick, and conditions may change rapidly, but there is no sign of Russian success so far.

One possible outcome is no advance at all, which would be hard for Putin to conceal from domestic audiences. At that point, I think his only option would be to dig in and try to retain currently occupied Ukrainian territory long enough for Western support to wane–a bit like Germany’s decision to hold fortified lines across Belgium and France from 1916-18.

A rainy, wet season is expected that will frustrate advances by either side. Ukraine expects deliveries of Western tanks and other equipment by late spring. Thus the most likely next phase is an attempted Ukrainian counter-offensive focused wherever the Ukrainian General Staff chooses.

If that counteroffensive succeeds, I think Putin’s options will become quite unpleasant for him. Then Russian would be in a similar position to imperial Russia in 1917.

If the Ukrainian advance should falter, then the war may enter a new stalemate phase, during which the main drama will be diplomatic. Would the US and European countries continue to support Ukraine or else start pressing for an armistice, which would give Putin time to rebuild for another invasion later? And where would players like China’s President Xi stand?

Call for Papers: Generous Listening in Organizations

The Vuslat Foundation and Tufts University’s Tisch College of Civic Life

Date and location: July 16 (dinner) until July 18 (lunchtime), 2023 Tufts University in Medford, MA

Propose contributions here: https://easychair.org/cfp/GLO23

Practicalities: We invite proposals on the theme of “Generous Listening in Organizations.” Proposals of up to 500 words are due on March 24, 2023. Draft materials based on accepted proposals will be due on July 3, 2023. Authors will be expected to read all the materials in advance and be prepared to discuss them at a symposium in Boston in July 2023. We will accept proposals for articles (defined as 7 pages or longer), shorter written briefs, posters, or exercises/experiments that can be piloted during the symposium. The content of proposed contributions may include new research findings, reviews of specific bodies of existing research, conceptual arguments, descriptions of interventions, empirical measures, and/or plans for new research. We will not accept previously published work.How to publish and disseminate these materials will be discussed during the conference. Whether a given contribution is included in any publication or public-facing website will be a joint decision by the Vuslat Foundation and the author.

Vuslat Foundation offers to pay travel expenses. Participants who offer articles (or comparable contributions in other formats) will be eligible for honoraria of $1,200. Those who offer briefs and other shorter contributions will not receive honoraria.

Background and Topic: We define “generous listening” as the skill of listening to oneself, to one another, and to nature with generosity, which enhances human connection. Listening is defined broadly, as meaning more than hearing words. It engages both the heart and the mind. Generosity implies values like openness, courage, curiosity, and responsiveness. The phrase “generous listening” is not widely used in published literature, but it relates to ideas like attentive listening, empathetic communication, and others. The purpose of generous listening is to reach vuslat, the freedom reached by reuniting with those estranged parts of the bigger whole.

Generous listening occurs in all human contexts, including political processes, families, classrooms, psychotherapy, the arts, and religion. For the purpose of this symposium, the focus is generous listening in firms and other organizations that have employees and explicit missions. The focus encompasses listening between managers and subordinates, among colleagues, or between employees and outsiders, such as customers or clients.

We are interested in whether and how generous listening can be enhanced by improving the skills of individuals and/or creating and altering physical and digital spaces, norms, or policies. We are also interested in whether and how generous listening improves outcomes for the individuals who are directly involved and for their organizations. Among the possible questions that papers might address (as an illustrative and non-exhaustive list):

- What are the components and elements of generous listening, including its essential skills?

- What are the challenges and barriers to generous listening?

- How should generous listening culture be measured in organizations?

- Can people be evaluated as generous listeners? How?

- Are survey questions about generous listening valid and valuable?

- How does feeling listened-to affect individuals?

- Which tools/means for generous listening are used in organizations today?

- Can generous listening be learned? Is learning and teaching it necessary?

- Does generous listening promote desirable processes within organizations, such as effective, inclusive, and innovative collaboration, communication, decision-making, and/or teamwork?

- How can organizations institutionalize generous listening at scale?

- Does generous listening relate to outcomes for organizations, such as employees’ satisfaction and retention and the organization’s strength and results and/or impact?

Advisory Committee

- Peter Levine, the Associate Dean of Academic Affairs and Lincoln Filene Professor of Citizenship & Public Affairs in Tufts University’s Jonathan Tisch College of Civic Life

- Dr. Çagri Hakan Zaman, the Director of MIT Virtual Experience Design Lab and a Lecturer in Design and Computation at the MIT Department of Architecture

- Lawrence Susskind, Ford Professor of Urban and Environmental Planning at MIT and the Director of the MIT Science Impact Collaborative

- Avi Kluger, professor of Organizational Behavior at School of Business at the Hebrew University

- Julia Minson, an Associate Professor of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government

- Vuslat Dogan Sabanci, Founder, Vuslat Foundation

- Selçuk Sirin, Professor in the Department of Applied Psychology at New York University

About Vuslat Foundation

Vuslat Foundation is a global initiative that fosters a deeper appreciation of listening as the essential element of all our connections. Established in Switzerland in 2020, Vuslat Foundation partners with academia, civil society, and the private sector to generate knowledge and research, develop methodologies and tools and build awareness and inspiration on generous listening.

About Tisch College

Tufts University’s Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life is a leader in civic education and engagement that sets the standard for higher education’s role in advancing the greater good. Tisch College combines education, research, and practice to serve as a hub for students, faculty, and community members who are committed to civic engagement and to its ability to change the world for the better.

impact of policies on COVID

We know some very important facts about COVID-19, including that vaccines work well. I do not think we understand as much as we should about the effects of government policies on the pandemic. For instance, any medical professional would wear personal protective gear while treating a patient with COVID, but it is less clear that requiring a population to wear masks has any effect. There is often a big slippage between voluntary behavior by trained professionals and large-scale mandates.

I did my own light modeling last April and found no effects of state masking and vaccination mandates on COVID mortality rates. I did find that COVID deaths by US state reflected the percentage of the population who had been in poor health before the pandemic, GOP vote share (Trump support meant higher death rates), Black/White segregation, economic inequality, the percent of the population over age 65, the incarceration rate, and a lower college graduation rate. (Statistically significant correlates: the first three. Adjusted r-square of the whole model = .699).

A new paper by Sun & Biseti examines the effects of state policies on county-level COVID death rates during the first 39 weeks of the pandemic, i.e., before vaccines were available and before masks were being widely recommended. They create a “stringency index” composed of “closures of schools, closures of workplaces, cancellations of public events, restrictions on gatherings, closures of public transport, stay-at-home orders, restrictions on domestic movement, and restrictions on international travel.”

Their model incorporates some similar contextual factors to mine but assesses different policies. It suggests that if every state had employed the maximum of all the stringent measures, the national death rate would have fallen by about 7% in 2020, but the benefits would have been greater “in counties with fewer physicians and larger shares of older adults, low-educated residents, and Trump voters” as well as “in rural areas and counties with higher social capital and larger shares of uninsured residents,” while the benefits would have been smaller “in counties with larger shares of [non-Hispanic] Black and Hispanic residents.” Although I don’t think we can tell from their model itself, it’s plausible that closing schools and businesses had no effect on deaths from the disease in big cities, although the closures were very hard on people.

An older but still valuable article (Sharma, Mindermann & Rogers-Smith 2021) looks at similar measures across subnational units (such as regions or states) of European countries. Their model finds significant benefits from stringent measures such as school closings, but smaller benefits during the pandemic’s second wave than its first. That finding illustrates that we are not in the domain of scientific laws here; we are in a messy zone of rapid change.

In my view, democratic governments and other legitimate institutions have a right to impose many kinds of restrictions to combat a disease. They must do their best to make decisions in the face of uncertainty and conflicting interests. No one’s fundamental human rights have been violated if a government closes schools for months or makes one wear a mask during a pandemic.

On the other hand, this does not mean that the most stringent measures are always effective or that we should be overly confident that we know what works. On the contrary, the lessons of this pandemic appear murky to me, and humility is warranted by all.

A lot of people are very sure what should have been done and are certain their opponents are badly motivated or fools. I think most of us did our best and still don’t have a firm basis to know what we should do next time.

Sources: Sharma, M., Mindermann, S., Rogers-Smith, C. et al. Understanding the effectiveness of government interventions against the resurgence of COVID-19 in Europe. Nat Commun 12, 5820 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26013-4; Sun, Y., & Bisesti, E. M. (2023). Political Economy of the COVID-19 Pandemic: How State Policies Shape County-Level Disparities in COVID-19 Deaths. Socius, 9, 23780231221149902. See also: what explains state variation in COVID-19 mortality?; we must be able to disagree about pandemic policies; vaccination, masking, political polarization, and the authority of science.

Bill of Rights Institute MyImpact Challenge

This post features outreach from our friends at the Bill of Rights Institute.

As you may know, research shows that students who participate in service-learning projects have higher academic achievement and awareness of current issues (Smith, et al 2019). However, it can be a struggle for teachers to offer innovative service-learning opportunities on top of everything else they do. At the Bill of Rights Institute, we have a plug-and-play solution!

Our MyImpact Challenge contest and curriculum direct students who want to give back in a way that increases academic outcomes, AND they can win prizes!

The contest, open to students aged 13-19, asks entrants to undertake a service project in their communities and send us a project report and an essay on how their project aligns with Founding Principles and Civic Virtues. We offer up to $40,000 in prizes to students and teachers, with a student grand prize of $10,000.

In addition, we offer a free, six-lesson service-learning curricular supplement that shows students how to design a service project targeted to local issues.

We are looking for partners in the following efforts:

- Advertising this year’s contest to students already involved in community service. We want to make sure that civically engaged students find out about the contest in time to enter by May 21. That means getting out the word to districts, teachers, and guidance counselors.

- Getting our service-learning curriculum into schools for 2023. Our six-lesson supplement helps students design local service projects tailored to the needs of their communities. It is a great addition to social studies courses ranging from 8th Grade Civics to AP Government. We’re happy to meet with any state or district that has an interest, and we want to make sure we’re reaching smaller districts as well as large ones.

- Setting up local civics fairs. Our long-term plan is to evolve the contest to include state-level competitions that filter up to the national contest. We are seeking local partners to launch in-person civics fairs either at the end of this school year or sometime in the 2023-24 cycle. Planning for several of these events is already underway, but we are hoping to significantly scale up activity in the coming year.

If you are interested in any of these initiatives, email Adam Brickley at abrickley@mybri.org to set up a meeting.

This is an exciting opportunity and a worthwhile effort, and we appreciate the work that our friends at BRI are putting into student civic engagement!

Celebrating Eagles During the Super Bowl

Today’s post comes to us from Dr. Terri Fine, our content specialist and the Associate Director of the Lou Frey Institute, in honor of Super Bowl Sunday (though I confessm, being a lifelong Patriot fan, I was not aware the Super Bowl was still played anymore). It looks at the American Bald Eagle as our national bird!

One of the great unofficial American holidays is Super Bowl Sunday. In 2023, the Super Bowl matchup brought together the Kansas City Chiefs and the Philadelphia Eagles. Philadelphia represents so much about U.S. civics, government, and history because the U.S. Constitution was written in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. But what about the team mascot, the American Bald Eagle? Why is the American Bald Eagle the national bird, and why does the image of the American Bald Eagle appear on so many government documents and artifacts including the Great Deal of the United States, the president’s flag, the mace of the U.S. House of Representatives, dollar bills and coins?

In 1789, the year that the U.S. Constitution took effect, the American Bald Eagle was chosen by Congress to represent the United States. What is unique about the American Bald Eagle that influenced Congress (and, likely, the Philadelphia professional football team) to select it as the national bird?

The American Bald Eagle is uniquely American—it is found only in North America and is seen as a symbol of strength and freedom. It has no predators and is not a bird that is typically eaten unlike, by contrast, the turkey, which is both hunted and eaten. When turkeys do fly, it is for short distances only, and generally not nigher than 50 feet, which is quite different from the American Bald Eagle, which flies solo and does not travel in flocks. Consider these symbols in the context of the emergence of the United States as an independent world superpower, “flying above” other nations that seek to emulate the United States in their government and economic systems.

Providence College talk on What Should We Do?

This is the video of my Jan. 31 presentation about my recent book, What Should We Do? A Theory of Civic Life at The Providence College Humanities Forum, along with a Q&A session with good questions from the audience. The presentation should make sense and, I hope, have some value for people who don’t read the book. I am grateful to my Providence College friends for the opportunity.

The Civil Rights Movement and the Sixties

I am visiting Wake Forest University today, mainly to speak at the Program for Leadership and Character. I will also visit a course on political activism in the 1960s. There, I’m planning to contribute a few remarks about the influence of the Civil Rights Movement.

By the time student radicalism became common on predominantly white college campuses in the Sixties, the Civil Rights Movement had already been underway for almost a decade. It was an inspiring model for Americans from the center-left to the far left. Specifically, about 1,000 mostly white, Northern students participated in Freedom Summer 1964, registering Black voters in Mississippi. As Doug McAdam shows, they returned radicalized by direct exposure to militant white supremacy. The summer changed them in many other ways; for instance, they turned bluejeans into the unofficial uniform of students in the Sixties by imitating rural Black organizers, who wore denim. Alumni of Freedom Summer became disproportionately influential in the left movements that followed. They also tended to exit the Civil Rights Movement itself–for a variety of reasons, including (appropriate) discomfort about their role in a Black-led struggle.

We misread the Civil Rights Movement if we assume that it had a coherent, centralized leadership structure–epitomized by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.–and a consistent message, as expressed in his “I Have a Dream Speech.” It was always a hotbed of debate and difference and always had many leaders. These facts would have been more evident to young radicals in the Sixties than they are today, because the King myth had not yet formed. However, young radicals also observed some actual features of the Civil Rights Movement that they increasingly disputed as the decade progressed, and these matters remain contested today.

First, the Movement developed and honored leaders: not one, and not just the Big Six (James Farmer, Philip Randolph, Whitney Young, Roy Wilkins, John Lewis, and King), but a cadre or layer of leaders across the country, including women. Leadership itself became more controversial after 1964 or so.

Second, the Movement treated the government as a target of demands. The goal was almost always to negotiate with government officials, from the police commissioner of a Southern city to Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daly to LBJ. The Movement eschewed two alternatives. It could have sought to become the government by winning elections or fomenting a revolution, or it could have shunned the government as illegitimate or un-reformable. Some Black leaders of the time advocated each of those strategies, but not the core leaders of the Movement. They wanted to be independent of the government and to influence it actively. The two alternatives (replacing or avoiding the government) became more popular in the student left as the Sixties enfolded.

Third, the Movement used existing social capital: organizations and associations. Churches were most important, but unions, businesses, newspapers, colleges, and fraternities and sororities also contributed. The genius of the original generation of Civil Rights leaders was to redirect inherited forms of social capital to new (political) purposes–for instance, by encouraging people already assembled in pews to boycott buses. Social capital had always been different in the urban North, it changed rapidly in the late 1900s, and leftists became critical of its major components, such as churches. Subsequent movements have sometimes tried to do without much organization or to create social capital almost from scratch, as with the communes, collectives, and consciousness-raising groups of the later 1960s.

Clearly, other changes also unfolded during the Sixties (which lasted until 1974 or so), including new causes, crises, ideologies, and constituencies. But I think the issues I’ve mentioned here still echo for today’s activists.

See also: social movements of the sixties, seventies, and today; why the sixties wore jeans; a different explanation of dispiriting political news coverage and debate; What is the appropriate role for higher education at a time of social activism? etc.