In 2010, the Florida Legislature unanimously adopted the Justice Sandra Day O’Connor Civics Education Act, which created a new statewide emphasis on civic learning. It required (1) that all middle school students complete a required course in civics; (2) that all middle school students (approximately 200,000 per year in Florida) take the statewide End-Of-Course Assessment (EOCA) at the end of 7th grade, which determines 30 percent of their grade for the year; (3) that civics content be included in the reading portion of the state’s English and Language Standards at every grade level from kindergarten through 12th; and (4) that student scores on the civics EOCA be incorporated into the computation of school grades under Florida’s School Accountability System (CS/HB 105, 2010). The EOCA is a multiple-choice assessment with approximately 60 questions aligned to the Florida middle school civics benchmarks. The four reporting categories that make up the middle school civics course include Origins and Purposes of Law and Government; Roles, Rights, and Responsibilities of Citizens; Government Policies and Political Processes; and Organization and Function of Government. Since the implementation of the assessment, student achievement has risen across all demographics, and 71% of all students taking the assessment during the 2017-2018 testing cycle passed the assessment with an achievement level of at least 3 (on a scale of 1 through 5).

The Four Reporting Categories

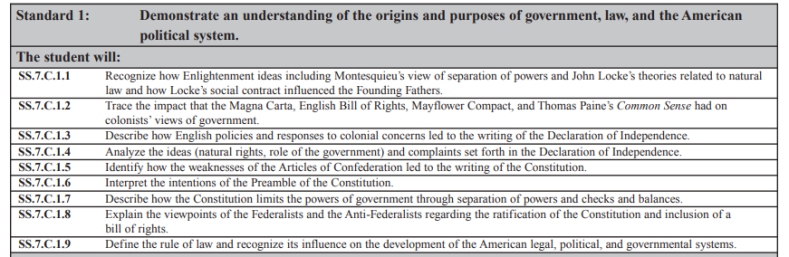

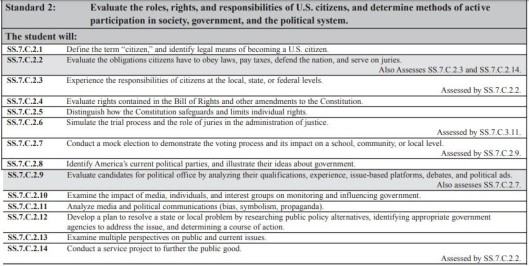

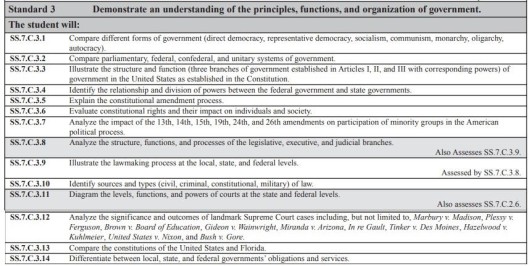

The four reporting categories within the civics course were developed by a committee of stakeholders to address areas of importance within civic learning while also seeking to differentiate the course from US History and, to a lesser degree, US Government. While the number of benchmarks in each category differ, there is clear evidence of a focus on the workings of government, the roles and responsibilities of citizens, and what we refer to as ‘Founding Documents’, particularly the US Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the Declaration of Independence.

Within each reporting category are a number of benchmarks that address the content to be taught. It is important to note, however, that these benchmarks are further broken down in the FLDOE Civics Test Item Specifications into Benchmark Clarifications, Content Limits, and Content Focus Terms. It is important to keep in mind that the Civics EOCA Test Item Specifications were created after the release of the Sunshine State Standards for Civics, which occurred in 2008. As such, the clarifications, limits, and content focus terms build on what may be left out of or be unclear in relation to the original standards and benchmarks.

The Benchmark Clarifications

The Benchmark Clarifications, it could be argued, are perhaps the most important element of the Civics Test Item Specifications. These clarifications provide deeper guidance to stakeholders on what to teach. Consider for example, Benchmark SS.7.C.3.12, which covers significant court cases that students should be familiar with. Table 1 provides an overview of the benchmark and related clarifications.

| Benchmark |

Analyze the significance and outcomes of landmark Supreme Court cases including, but not limited to, Marbury v. Madison, Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown v. Board of Education, Gideon v. Wainwright, Miranda v. Arizona, In re Gault, Tinker v. Des Moines, Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, United States v. Nixon, and Bush v. Gore. |

| Benchmark Clarification 1 |

Students will use primary sources to assess the significance of these U.S. Supreme Court cases. |

| Benchmark Clarification 2 |

Students will evaluate how these U.S. Supreme Court cases have had an impact on society. |

| Benchmark Clarification 3 |

Students will recognize and/or apply constitutional principles and/or rights in relation to the relevant U.S. Supreme Court decisions. |

Table 1: 2012 FLDOE Civics End-of-Course Test Item Specifications (FLDOE, 2012, p. 65)

In looking at the benchmark and clarifications provided in Table 1, note that it explains not only what aspects students need to know, but how they will be expected to demonstrate it. These emphasize the use of primary sources, critical thinking, and constitutional principles; indeed, this is reflective of the Test Item Specifications as a whole.

The Content Limits

‘Content Limits’, as defined by the Test Item Specifications, “define the range of content knowledge and degree of difficulty that should be assessed in the test items for the benchmark” (FLDOE, 2012, p. 16). In other words, they provide the teacher (and the students!) information on what they do not have to know in order to meet the expectations of this benchmark. For our sample Benchmark SS.7.C.3.12, for example, the Content Limit states that “Items will not require students to recall specific details of any U.S. Supreme Court case (FLDOE, 2012, p. 65). Within this context, then, students need to know the broad parameters and underlying constitutional principles about a particular case, but not specific details.

Content Focus Terms

‘Content Focus Terms’ address content not necessarily referenced in the benchmark or benchmark clarifications but should be known in order to demonstrate proficiency within the limits of that benchmark. Table 2 provides an example of the content focus for SS.7.C.3.12.

| Benchmark |

Analyze the significance and outcomes of landmark Supreme Court cases including, but not limited to, Marbury v. Madison, Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown v. Board of Education, Gideon v. Wainwright, Miranda v. Arizona, In re Gault, Tinker v. Des Moines, Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, United States v. Nixon, and Bush v. Gore. |

| Benchmark Clarification 1 |

Students will use primary sources to assess the significance of these U.S. Supreme Court cases. |

| Benchmark Clarification 2 |

Students will evaluate how these U.S. Supreme Court cases have had an impact on society. |

| Benchmark Clarification 3 |

Students will recognize and/or apply constitutional principles and/or rights in relation to the relevant U.S. Supreme Court decisions. |

| Content Focus |

These terms are given in addition to those found in the standards, benchmarks, and benchmark clarifications. Additional items may include, but are not limited to, the following: District of Columbia v. Heller, juvenile rights, rights of the accused, and segregation. |

Table 2: 2012 FLDOE Civics End-of-Course Test Item Specifications (w/Content Limit) (FLDOE, 2012, p. 65)

Within the context of this benchmark, then, students are also expected to be familiar with specific terms that connect to constitutional principles (such as the rights of the accused), specific case language (segregation and juvenile rights), and an additional significant court case that occurred between the adoption of the Next Generation Sunshine State Standards for Social Studies and the drafting of the Civics End of Course Assessment Test Item Specifications.

Taken together, the Benchmark Clarifications, Content Limits, and Content Focus Terms provide an explicit and detailed overview of what teachers are expected to teach and what students are expected to know for civics in Florida. So let us turn our attention to the four standards and consider what areas are covered throughout this course.

The Four Standards

The four main standards provide a course-long overview of what needs to be taught throughout the course. Each standard contains a particular number of benchmarks. All told, there are 40 benchmarks across 40 standards, and of these, 35 are directly assessed. A close review of the standards demonstrates the breadth of Florida’s approach to civics and the heavy emphasis placed on the Constitution and the structure and function of government.

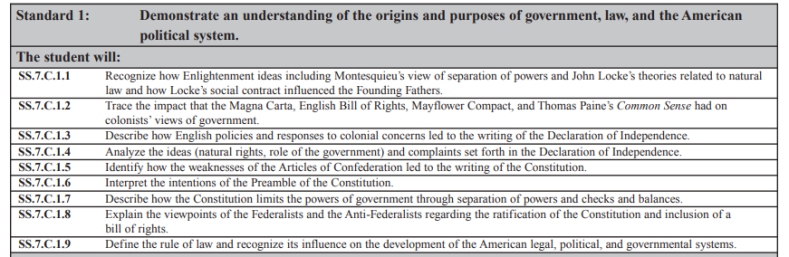

Origins and Purposes of Law, Government, and the Political System

Table 3: Overview of Standard One

The first standard addresses the path towards the development of the US Constitution, beginning with the Enlightenment ideas that influenced the Framers and continuing through the drafting and implementation of the US Constitution. Generally speaking, students are expected be able to understand the arguments of the Declaration of Independence, know how the ideas of Montesquieu and Locke influenced the Founding Fathers, identify the problems with the Articles of Confederation, contrast the views of the Federalists and Anti-Federalists, explain the responsibilities of government as described in the Preamble, and understand separation of powers and checks and balances. There is a heavy focus in this standard on early principles that shaped an approach to American representative government.

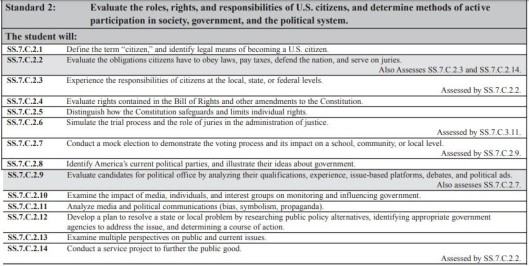

Roles, Rights, and Responsibilities of Citizens

Table 4: Overview of Standard Two

The second standard dives deeper into elements of citizenship and civic engagement with government. It is a relatively broad category, covering elements of citizenship, our obligations, rights, and responsibilities under the Bill of Rights and our representative democratic system, elections, the media, and multiple perspectives. This standard also includes benchmarks that have students engaging in the practices of civic life, including elections, the justice system, and public policy. It should be noted here that much of this standard does indeed draw on the idea that the responsibilities of citizenship are just as important as the rights of citizenship.

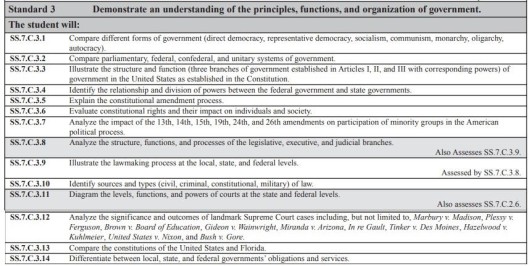

The Principles, Functions, and Organization of Government

Table 5: Overview of Standard Three

The third standard goes heavy into the US Constitution, particularly Articles I, II, and III. In order to demonstrate proficiency within this category, students must learn how government is supposed to function, the powers of the three branches, the lawmaking process, the role of the courts, significant cases, and how federalism works. This standard also covers the expansion of rights through the amendment process and students also touch on the Florida Constitution. Again, however, we continue to see a heavy emphasis on the US Constitution.

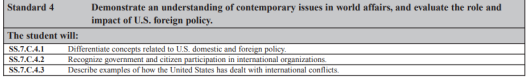

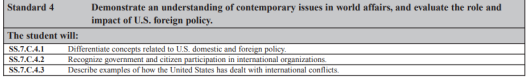

US and the World

Table 6: Overview of Standard Four

The final overarching standard within Florida’s civics course dives into US foreign and domestic policy. This includes having students consider US foreign conflicts throughout the 20th and 21st century and understand the different ways each was addressed. Students are also expected to understand the difference and relationship between US foreign and domestic policy and citizens can engage with international organizations of various stripes. Interestingly, this standard’s focus on US foreign policy goes beyond the expectations of civics courses in many other states.

The Civics End of Course Assessment

Florida’s civics end of course assessment is a selected response assessment, developed in collaboration with Pearson, and has been a mandatory assessment for middle schoolers in Florida since 2013. The Justice Sandra Day O’Connor Civic Education Act does not require students to pass the exam, but it does require schools to count the exam as 30% of a student’s final grade in the course. The exam itself draws directly on the learning expectations and content found in the Civics End of Course Test Item Specifications, which itself includes sample items that preview the assessment. Teaching to the standards, benchmarks, and benchmark clarifications will best prepare students to succeed. So what does this assessment look like?

The Structure of the Civics End of Course Assessment

The End of Course Assessment contains 52-56 items, on average, with some small variable number of these items being piloted in each testing cycle, thus not counting towards the final score. While the expectation is that students will complete the test in 160 minutes, in practice most schools provide students with as much time as they need to complete it. Each item on the assessment has a question and four options to choose from; the Civics End of Course Test Item Specifications provide item writers (and really all stakeholders) with clear instructions on how to construct said items, including appropriate wording, the use of plausible distractors, parallelism, and types of stimulus (FLDOE, 2012, pp. 2-4). At the same time, the item specifications make clear that the “… reading level of the test items should be grade 7, except for specifically assessed Civics terms or concepts” (FLDOE, 2012, p. 2).

One of the issues that often causes confusion for stakeholders is the difference between item difficulty and item cognitive complexity. Simply put, the cognitive complexity of items is stable from year to year, while at the same time, item difficulty might change depending on the students that take the test in a particular testing cycle. The psychometricians that deal with validity, reliability, and scoring of the assessment cannot identify item difficulty until after students have taken the test. Figure 1 illustrates the determination of item difficulty.

Figure 1: Item Difficulty

Item difficulty, then, refers to how many students might get a question correct; it can change with each administration of the assessment. Cognitive complexity, on the other hand, remains consistent and is identified at the formal item review that takes place each fall to review new sets of items provided by Pearson. Cognitive complexity, in simple terms, refers to how many mental steps students must go through in order to answer a question. The Florida Civics End of Course Assessment uses Webb’s Depth of Knowledge as a complexity framework, and items are classified as being low, moderate, or high complexity items. It should be noted, as well, that you can have an item that is low complexity and high difficulty; remember that difficulty is about how many students get the question correct. Page 12 of the Florida Civics End of Course Assessment contains an overview of activities across cognitive complexity levels in order to provide teachers with guidance on both instruction and assessment. A large part of each assessment is made up of moderate complexity items; table 7 provides a breakdown of cognitive complexity in relation to test construction.

Table 7: Percentage of Points by Cognitive Complexity Level for Civics EOC Assessment

The Development, Review and Revision Process

Since the beginning of the Civics End of Course Assessment development process, items have been provided to the Test Development Center (a division of the Florida Department of Education) by Pearson. Each year, Pearson provides approximately 150 to 200 new items for review and eventual piloting across upcoming testing cycles. These items are developed in a collaboration between Pearson and state assessment personnel, and follows a generally fixed process, and are generally intended to provide new items across every benchmark.

At the start of the development cycle, Pearson provides item writers (none of whom are practicing Florida teachers in order to avoid conflicts of interest) with a set item order of anywhere between 15 and 25 items on average. Writers are provided with the benchmark, benchmark clarification, content focus term (if applicable) and cognitive complexity level they are asked to write to. These are then submitted to Pearson for internal review and approval and provided to the state for the next phase of the review process. There are a number of steps within that process that involve a back and forth between the Social Studies Test Development Coordinator and Pearson, but eventually, items go out to a committee of community members and eventually educators.

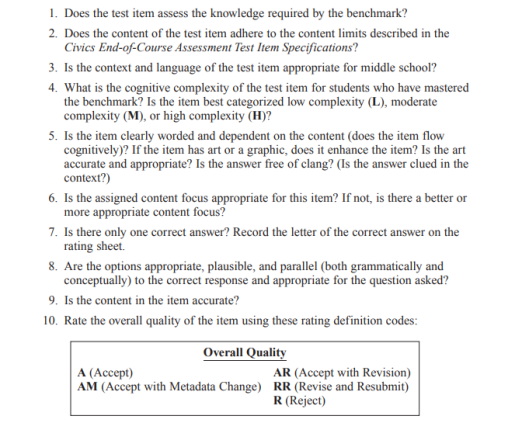

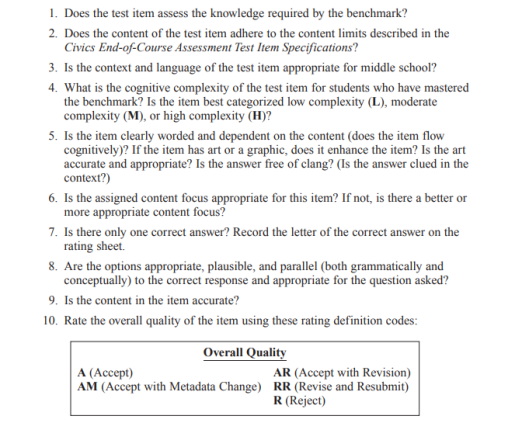

The Bias and Sensitivity Committee reviews items for areas of concern that could cause potential issues for students and provide a report on identified issues to the Social Studies Test Development Coordinator and to Pearson. This report is then shared with Item Review Committee. This last committee is made up of practicing civics teachers, teacher leaders, district social studies supervisors, and content area experts, and their main task is to review the penultimate draft of items for a number of areas. Figure 2 provides an overview of what these item reviewers are looking for.

Figure 2: The Item Review Process

Each individual at the table during item review brings with them experience in or expertise with civics instruction and content as addressed by Florida’s benchmarks, and is assigned one particular role during the process. One person may be tasked with identifying the cognitive complexity (which may differ from that identified by the original item writer), for example, while another may be asked to ensure that the content of the item is accurate. However, following the initial table response on an item, each reviewer is allowed to provide a perspective across each of the 9 areas addressed in Figure 2. Pearson ensures that they have staff present to assist in revising items that may require some additional work. Once items have been accepted, they are then sent on to the psychometricians, who will determine validity and reliability through piloting them items on upcoming assessments.

This brings us, then, to instruction. What does all of this look like in the classroom?

What Gets Taught in the Civics Classroom?

Research done under the auspices of the Lou Frey Institute and the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement following the 2015-2016 testing cycle provides a general perspective on teaching the civics benchmarks in Florida classrooms. The research summarized in this section is provided in greater detail in a report authored by Dr. Racine Jacques and provided at the Lou Frey Institute website (http://loufreyinstitute.org/reports/2). The reader is encouraged to review the report available at the provided link.

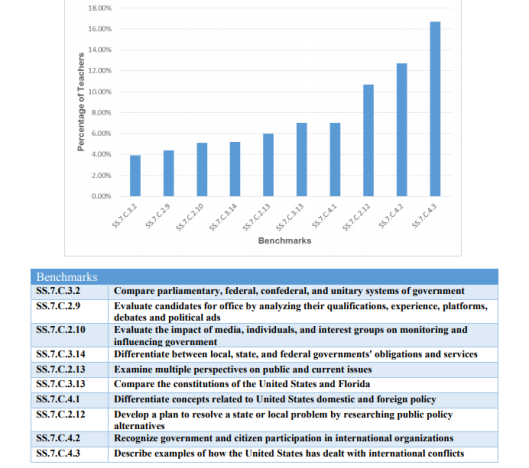

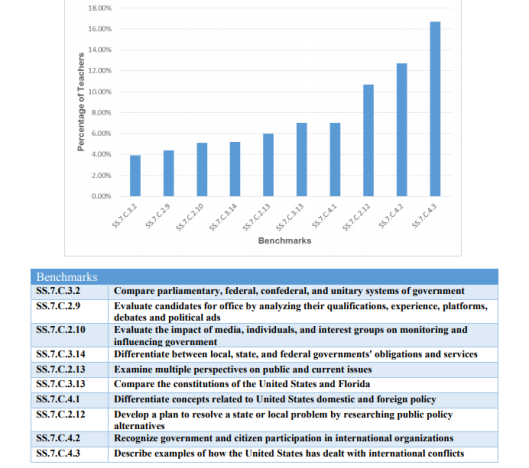

As mentioned earlier, 35 of the 40 benchmarks are directly assessed by the end of course assessment. The other 5 are grouped with connected benchmarks and assessed through them. According to research, coverage is a significant issue and an area of concern. Approximately half of the more than 400 civics teachers that were surveyed felt that they were unable to adequately cover all assessed benchmarks over the course of the school year. Looking at the data, the average number of omitted benchmarks was 3. One of the most common groups of benchmarks that were omitted come from Standard 4 and related to a consideration of US foreign policy within a civics education context. This was likely less because of difficulty and more because they simply ran out of time to cover the material. Figure 3 provides and illustration of which benchmarks were most often omitted from instruction.

Figure 3: The Most Common Omitted Benchmarks

At the same time, respondents felt that they had some significant issues in adequately instructing students in some benchmarks. SS.7.C.2.12, for example, is an action civics oriented benchmark that asks students to involve themselves in considerations of public policy. Other areas of concernfrom a recent survey of Florida social studies district supervisors include SS.7.C.2.5, around individual rights; SS.7.C.2.10, around the ways in which media, individuals, and interest groups impact government; SS.7.C.3.4, around federalism; and SS.7.C.3.5, around the amendment process. Anecdotal observations by FJCC staff, gained through work with practitioners, also indicate significant instructional concerns around the many Supreme Court cases and constitutional principles contained in SS.7.C.3.12.

As described in the survey, the reasons for both difficulty of instruction and lack of instruction generally boiled down to 3 main explanations: student responsibility, teacher responsibility, or structural constraints. Student responsibility often boiled down to the supposed inability of the student to learn the material, while teacher responsibility pointed to issues with teacher content knowledge. Structural constraints could, in short, be retitled as ‘Issues with time’; for the most part, respondents who identified structural constraints as an issue struggled to cover the material adequately in the time provided. For more information on this aspect of the research survey, please read the original report available at http://loufreyinstitute.org/reports/2.

How Does Civics Get Taught in Florida Classrooms?

One of the areas of interest that the aforementioned study asked respondents to consider was how they actually approach civics instruction. Perhaps not surprisingly considering the content of the civics course, more than 90% of teachers claimed to address current events a number of times throughout the year, which 3/4ths of all teachers claiming they address current events every week. A similar fraction of teachers also involved their students in civic learning through the use of computer games, primarily using the popular ‘iCivics’ platform (https://www.icivics.org/). Almost 40% of teachers said they involved students in debates at least once or twice a month. It should be noted here, however, that how they involve students in debates what these debates look like is not clear. Involving students in ‘lived civics’ does occur to at least some degree. Mock elections, mock trials, service learning, and classroom discussions and debates all had some level of participation.

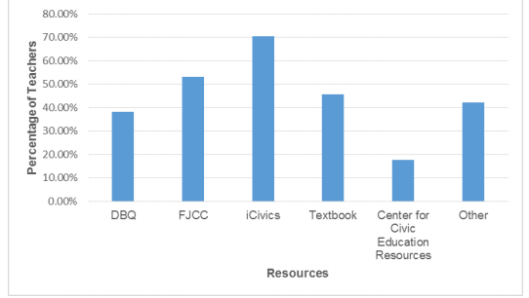

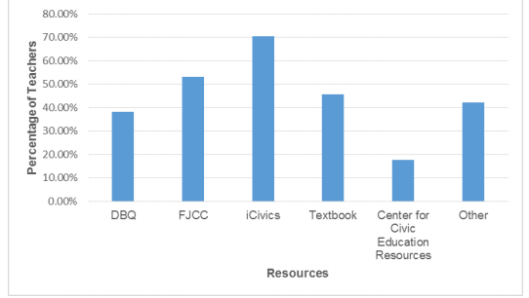

When it comes to resources, Figure 4 provides a good overview of the most used resources among respondents to the survey.

Figure 4: Primary Instructional Resources

Based on the data, resources from iCivics and the Florida Joint Center for Citizenship (FJCC) are the most commonly used resources for civics instruction. iCivics is perhaps best known for its games, while FJCC (http://floridacitizen.org/) offers a more diverse collection of tools, including lesson plans, content videos, practice assessments, and more. More recently, FJCC launched Civics360 (http://civics360.org/), with more than 100,000 registered users and a student-oriented approach to instructional tools (note that Civics360 did not exist at the time of the original research summarized here). For a deeper discussion of resource selection and implementation, please read the original report available at http://loufreyinstitute.org/reports/2.

A Word on Florida’s National Reputation

Any summary of civic education in Florida would be lacking without some mention of Florida’s national reputation for civic learning and instruction. Since the passage of the Justice Sandra Day O’Connor Civics Education Act, national attention has focused on Florida as one of the few states with a mandatory and comprehensive civics course at any level, let alone one with a high stakes assessment attached to it. The CivXNow Coalition, made up the nation’s leading philanthropic, academic, and instructional supports of civic education, has identified Florida’s model of success as one for states to emulate:

“If every state enacted a policy like Florida’s–and consistently supported that legislation with funds for professional development, materials, assessment, and other interventions–America’s young people would be on course for more active and informed civic engagement throughout their adulthood as well. That means that pronounced civic deficits in Florida to date–low levels of voter turnout, membership in groups, trust, and volunteering–will begin to improve, and civil society will be stronger.” (Levine & Kawashima-Ginsberg, 2017, p. 14).

More information on Florida’s national reputation, and the lessons it provides the nation, is available at CivXNow ( https://www.civxnow.org/).

Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement (PACE) has launched a pilot funding and learning initiative to invest in and promote engagement at the intersection of faith and democracy. The

Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement (PACE) has launched a pilot funding and learning initiative to invest in and promote engagement at the intersection of faith and democracy. The * NEW – National Civic League looking to hire Civic Engagement Program Director (in Denver office). Read more

* NEW – National Civic League looking to hire Civic Engagement Program Director (in Denver office). Read more

Tuesday, June 4th

Tuesday, June 4th Wednesday, June 5th

Wednesday, June 5th

Wednesday, June 12th

Wednesday, June 12th Wednesday, June 12th

Wednesday, June 12th