About one in four Americans supports reparations for slavery. There is a racial split on that question, with up to three in four African Americans–but only 15% of whites–in favor.

If you think that justice demands reparations, you should support them. You might not make reparations your main criterion for choosing candidates in a given political contest, because you might vote on other grounds, but you should endorse proposals that you believe are just.

Here I want to address a different issue. I’ll offer an explanation (not a justification or a critique) of the importance of reparations in the mentality of left-leaning Americans.

I think that many Americans on the left are torn between two political positions, each coherent on its own but in tension with the other:

1. A strong version of New Deal/Great Society liberalism and/or social democracy, in which the nation-state intervenes assertively in the economy to promote equity and environmental sustainability. This stance is compatible with enthusiastic support for voting and democratic processes. It requires a lot of trust in the state and a willingness to entrust state actors with the ability to, for example, investigate how much wealth (not just annual income) you have, which schools your kids will attend, and which health treatments will be paid for, given data about your body.

Martin Luther King, Jr., provides a classic statement of this view when he recalls the launch of the Great Society: “A few years ago there was a shining moment in that struggle. It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor — both black and white — through the poverty program. There were experiments, hopes, new beginnings.”

2. A deep suspicion of the United States government as white-supremacist, patriarchal, and colonialist: as a continuous entity that has played a leading role in genocide, enslavement, and apartheid, in part because those policies have sometimes been popular among the white majority of the country.

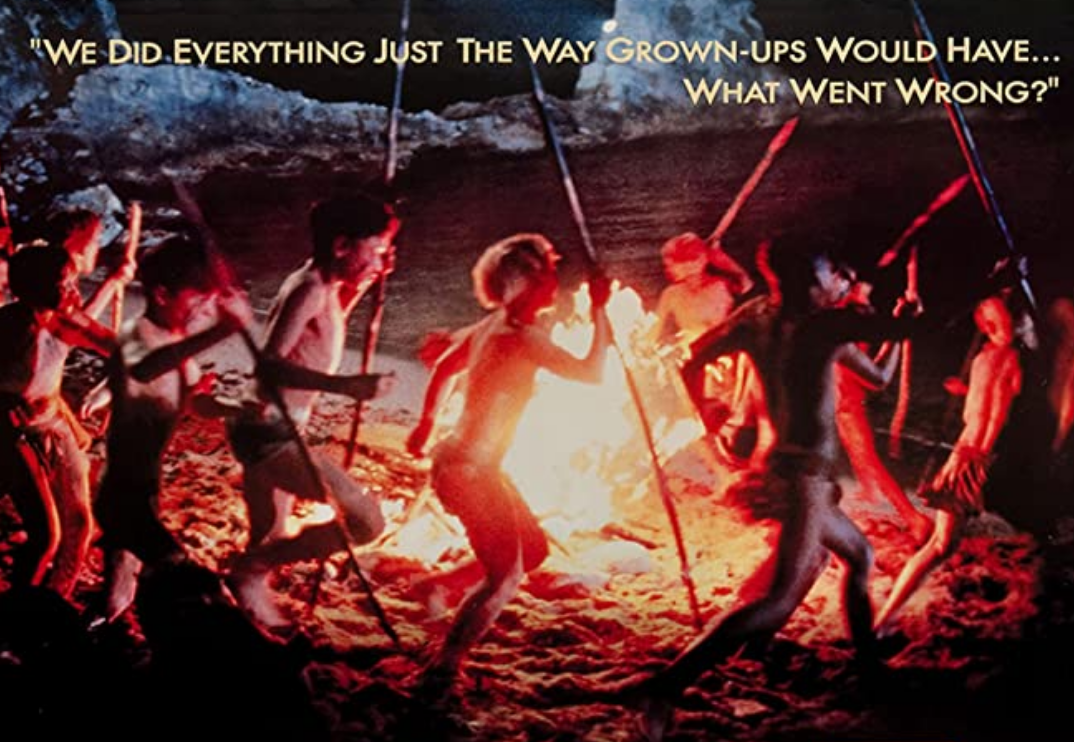

It’s debatable what positive program follows from the second position, but in practice, it can mean support for local initiatives, nonprofits, women- and minority-owned businesses, and autonomy at the neighborhood level. Malcolm X provides a classic text for this view:

The white man, the white man is too intelligent to let someone else come and gain control of the economy of his community. But you will let anybody come in and control the economy of your community, control the housing, control the education, control the jobs, control the businesses, under the pretext that you want to integrate.

… we haven’t had sense enough to set up stores and control the businesses of our community. … But the political and economic philosophy of black nationalism…the economic philosophy of black nationalism shows our people the importance of setting up these little stores, and developing them and expanding them into larger operations. Woolworth didn’t start out big like they are today; they started out with a dime store, and expanded, and expanded, and expanded until today they are all over the country and all over the world and they getting some of everybody’s money. …

So our people not only have to be reeducated to the importance of supporting black business, but the black man himself has to be made aware of the importance of going into business. And once you and I go into business, we own and operate at least the businesses in our community.

Note that this position is compatible with certain forms of libertarian thought but not with social democracy.

It is not embarrassing to be drawn to two incompatible views. The social world is complicated, and there are good reasons in favor of many positions. However, when you feel the pull of two incompatible ideas, a deciding factor becomes very important.

Reparations play that role for the American left. If the United States government were to pay reparations, that would tilt many left-leaning people from the second position to the first: from Malcolm to Martin, if those labels are helpful. The impact would be especially strong if Congress and the president decided to pay reparations of their own volition–not by grudgingly negotiating with a social movement–and if the payment were substantial.

The underlying theory here is similar to Homer-Dixon et al (2020). An ideology is a complex system that consists of numerous ideas with logical links among them. It cannot be described adequately by placing it on one left/right spectrum, nor even several such continua at once. It is not a point in logical space but a structure of ideas.

In complex systems, we frequently see multiple equilibria, and specific nodes have surprisingly large impact because of their location. A single node can tilt the system from one equilibrium to another.

My conjecture is that reparations plays such a role in the system of the ideology of the American left. Left-leaning people may not rate it as the most important issue. They may not even endorse it whole-heartedly. But it (perhaps uniquely) can tilt them from a libertarian equilibrium to a social-democratic equilibrium.

This is an empirical conjecture for which I do not have data. To test it, we would have to explore the epistemic network of left-leaning Americans, either by analyzing large bodies of text or by surveying individuals about their ideas and perceived connections among their ideas.

See also: on Hillary Clinton and Julius Jones of #blacklivesmatter; ideologies and complex systems; and unveiling a systems map for k-12 civic education (for a methodological analog).

Earlier in the pandemic, NCDD hosted conversations to help the dialogue, deliberation, and public engagement community explore how to respond to the needs arising immediately in our own communities. These conversations primarily focused on how to continue our work in a virtual format and how to help our communities stay connected while physically distanced. Now, two months into this experience, we would like to launch a conversation on what we are learning about our communities, and how we might help community members recognize what they see as important to sustain or nurture going forward.

Earlier in the pandemic, NCDD hosted conversations to help the dialogue, deliberation, and public engagement community explore how to respond to the needs arising immediately in our own communities. These conversations primarily focused on how to continue our work in a virtual format and how to help our communities stay connected while physically distanced. Now, two months into this experience, we would like to launch a conversation on what we are learning about our communities, and how we might help community members recognize what they see as important to sustain or nurture going forward.