What a thrill to learn that Cecosesola (Central de Cooperativas de Lara) -- the Venezuelan network of community organizations from low-income areas – has won the 2022 Right Livelihood Award! Cecosesola is a federation of co-operatives and other groups that has created its own distinct social and economic ecosystem. Since 1967, the group has relied on commoning to develop a humane provisioning system that meets the needs of more than 100,000 families across seven Venezuelan states.

The Right Livelihood Award cites Cecosesola for "establishing an equitable and cooperative economic model as a robust alternative to profit-driven economies." It has achieved this in the face of serious problems in Venezuela – a financial crisis, food shortages, hyper-inflation, and a massive out-migration of 7 million people.

Cecosesola doesn't simply provide competitive market prices for food, healthcare, loans, and cooperative funeral services, among other ventures. It changes well below normal retail prices. You could say that Cecosesola has learned how to ignore the market and set its own terms for providing goods and services. Its economic activities are almost entirely self-financed, and its internal governance and culture of solidarity and trust reject the standard management practices of businesses and bureaucracies.

Over five decades Cecosesola has made it a priority to develop a culture of transparency and mutual support. It is committed to an ethic of fairness and concern for well-being. These values and practices have flourished through the group's radically horizontal system of collaboration that pointedly avoids hierarchical control. The culture enables Cecosesola to deal with changing circumstances and crises in highly efficient, flexible, and adaptive ways. "We are just one big conversation," as one of its members said in an interview.

My late colleague Silke Helfrich first alerted me to this fantastic organization after she met with many of its members in the early 2010s. Her interview with them was published in our book Patterns of Commoning in 2014. We later wrote an interpretive summary of Cecosesola in our 2019 book Free, Fair and Alive, seeing Cecosesola as an "omni-commons" because it serves as a hosting infrastructure for all sorts of experimental, niche ventures in commoning. Silke last year nominated Cecosesola for the Right Livelihood Award.

Cecosesola's food operations have become so large and socially sophisticated that they set their own prices, independent of markets. They operate their own trading spaces — four huge marketplaces, one in each section of the state capital, Barquisimeto, a metropolis of 1.25 million people in the northwest of the country.

When we published the piece about Cecosesola, it was selling some 700 tons of fresh produce at a single price per kilo, which is significantly lower than the prices charged by conventional grocers. The net effect was to driven down market prices in the region, allowing about 700,000 people to enjoy both lower prices as they secure half of the food they need.

When Silke interviewed a few of the hundreds of members of the federation in 2011, here are a few things that members shared:

- "We are less interested in producing 'something that's ours' than creating 'us.' We want to understand and change ourselves. That generates a kind of collective energy….We try to conceive of Cecosesola as a personal process of development, not as work."

- "We don't pay ourselves wages. Instead, we pay an advance on what Cecosesola will presumably make. But we don't work in order to make a profit or to accumulate goods. That isn't what drives us, and that's why our surpluses are relatively modest."

- "Everybody gets paid the same amount. The cook earns the same as the bookkeeper, but we also take different needs into account, for example, if someone has just had a baby. The only exception is the physicians. They get about twice as much…"

- "The decisive factor is that we don't follow the market or the market price. If prices for tomatoes and potatoes go up someplace, that doesn't mean that we'll raise prices, too. What matters for us is that we earn what we need."

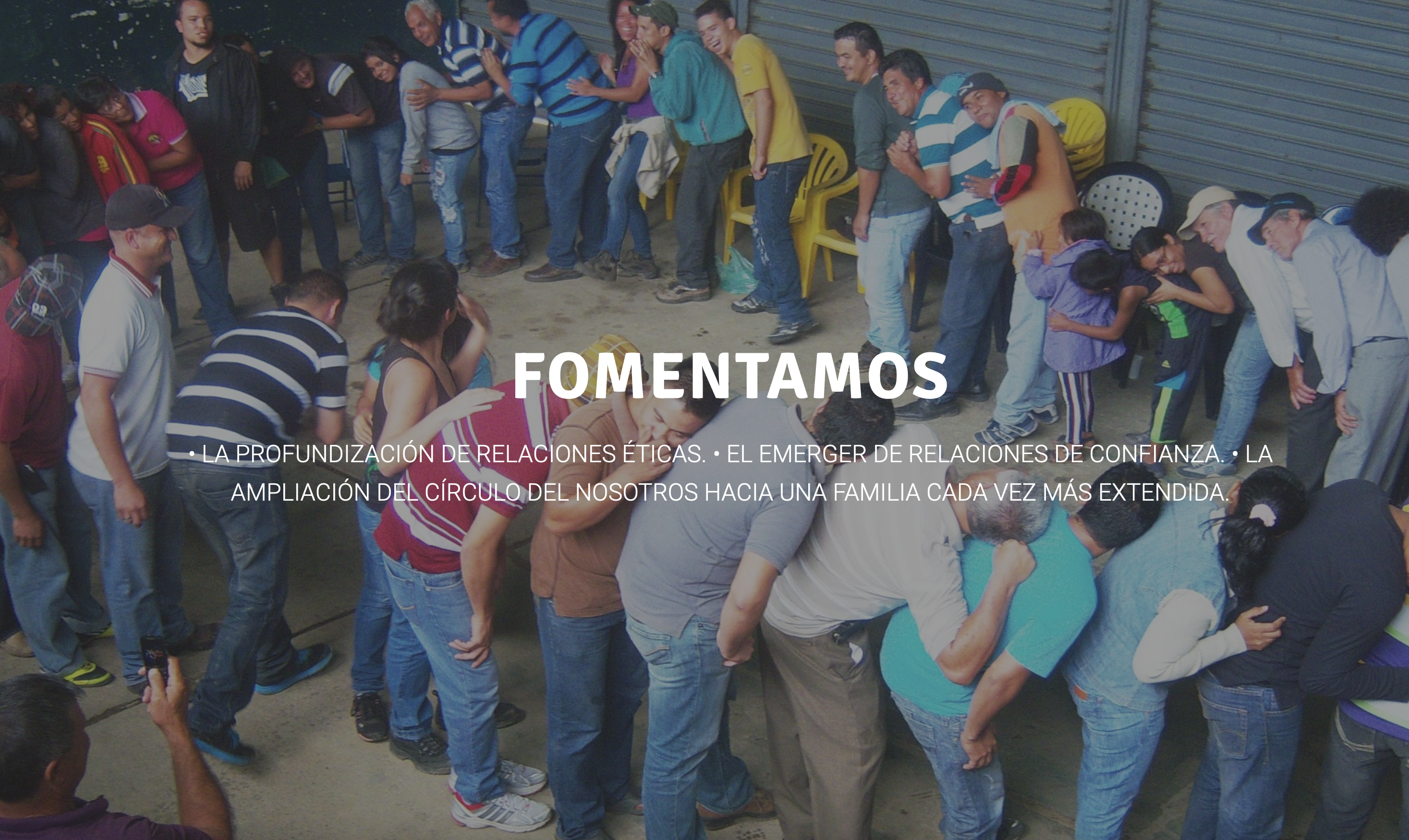

The Spanish above translates as: "The deepening of ethical relations. The emergence of trusting relationships. The widening of the circle of "we" towards an increasingly extended family.

In Free, Fair and Alive, Silke and I returned to consider the Cecosesola experience:

Cecosesola asks a simple question to its farmers and service providers, all of them members of the federation: what do you need to produce the harvest that you do? (It is exactly the same question some CSA members ask the CSA farmer so that they can share the risk of provisioning.) The rural cooperative members working in the fields, and Cecosesola members who coordinate the federation or sell at markets in Barquisimeto, gather in the shadow of a tree. While sitting on simple wooden benches, their casual chat slowly turns to the serious work of estimating what is needed for production: So many days of work, this much seed, that much fuel, enough irrigation pipes, and so forth. The more experienced members remind the less experienced ones that things may fall apart and need to be repurchased, or that more mule fodder may need to be bought because the last 800 meters up steep hills will increase transportation costs. Bit by bit, members bring their situated knowing to bear. Together, they identify the very concrete costs for production in their specific conditions of life and farming. Producers and distributors (people from Cecosesola’s central office in the city; traders or middlemen in the conventional economy) coordinate together.

This is price-making, right in front of everybody’s eyes – but not in any anticompetitive, monopoly-driven sense! Each cooperative within the Cecosesola system does its own calculations, and in the end, the federation sums up the results of all the meetings, adds in some additional sums for extras and losses (yes, tomatoes get spoiled on their way to the capital and some get stolen at the market).

Then Cecosesola takes a radical, counterintuitive step: “We decouple the price of vegetables from the time and effort we put into them,” as coop member Noel Vale Valera explains. “We add up the number of kilograms produced across the entire produce range, on the one hand, and we add up the costs on the other hand. Then we divide one by the other to figure out our average price per kilogram. Our yardstick is simply the production costs including what the producers need to live …What matters for us is that we earn what we need.” Cecosesola members don’t think of producers, traders, and consumers as separate, each having separate interests. They think of everyone as a whole in which everyone has to meet their needs along with the entire enterprise.

Vale’s colleague Jorge Rath insists, “This system saves people quite a lot of money … Our price per kilogram reduces red tape, we don’t work with middlemen, and seasonal fluctuations don’t make a difference, either.” The single per-kilo price for all produce emerges from open discussion among all those who produce and the many others who collaborate with them. In the end, it is no surprise that costs and therefore prices are significantly lower than those of conventional markets. There are no hidden costs, thanks to the trust and transparency within Cecosesola. There are no costs for marketing and advertisements. There are no intermediaries charging inflated prices to act as a wholesaler or distributor. Cecosesola is able to show money efficiency and price sovereignty.

The really stunning fact is the remarkable strength of Cecosesola as a provisioning system in times of political and economic crisis. It is basically due to the federation’s capacity to react quickly to dramatically changing circumstances.

A hearty congratulations to Cecosesola for the recognition made by the Right Livelihood Award! May your work be an inspiration and model to others seeking better ways to meet needs in fair, participatory, and effective ways!

The point of a world electrical grid is to re-engineer hub-and-spoke transmission networks designed for central power plants so that electricity can be easily transmitted between daytime to nighttime regions of the world, and between the Global North and South. The infrastructure would make it more feasible for countries to rely on renewable energy because the grid would solve the problem of intermittent energy flows (no solar energy can be generated at nighttime; the wind is not always blowing).

The point of a world electrical grid is to re-engineer hub-and-spoke transmission networks designed for central power plants so that electricity can be easily transmitted between daytime to nighttime regions of the world, and between the Global North and South. The infrastructure would make it more feasible for countries to rely on renewable energy because the grid would solve the problem of intermittent energy flows (no solar energy can be generated at nighttime; the wind is not always blowing).