Ukrainian friends have been telling me for a decade about the value of decentralization in their country. Some have even argued that it helped prepare Ukraine for an effective and motivated military defense.

A new paper by Arends, Brik, Herrmann and Roesel (2023) offers relevant quantitative evidence. The authors explain that, in “2014, the Parliament of Ukraine amended the budget code to entitle villages and cities which amalgamated voluntarily into larger local governments, so-called ‘territorial hromadas’ …. Hromadas therewith become independent from local branches of the national administration. The newly created local governments also qualified for a 60 percent share of the personal income tax collected within their jurisdiction.”

In 2015, the hromadas gained power over schools, libraries, hospitals and health centers, local roads, and fire and emergency services. In 2018, they were also given “ownership of formerly state-owned land within their jurisdiction.”

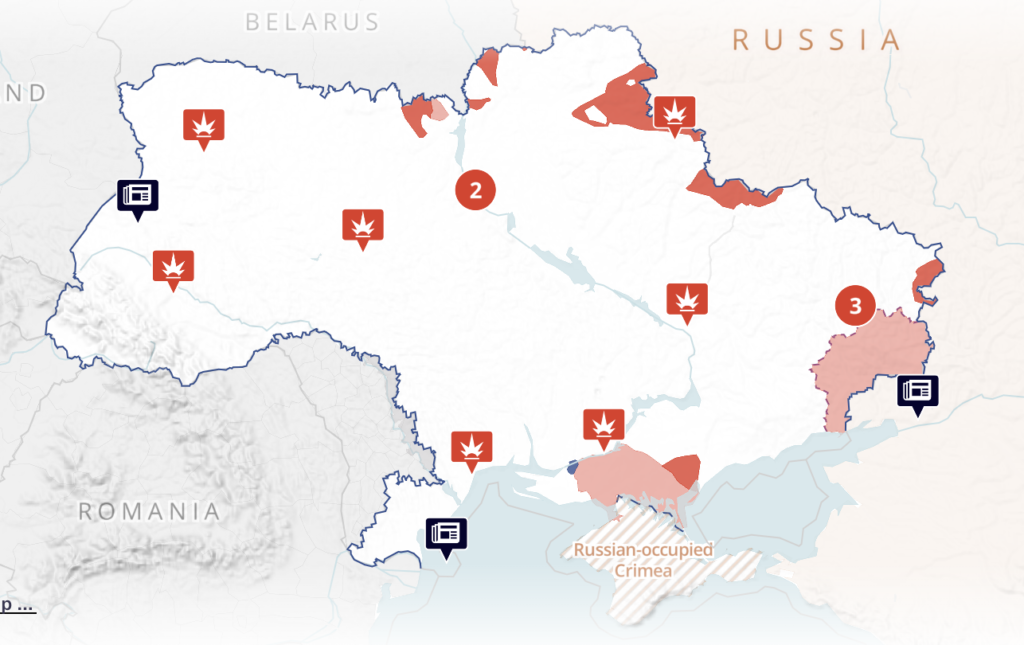

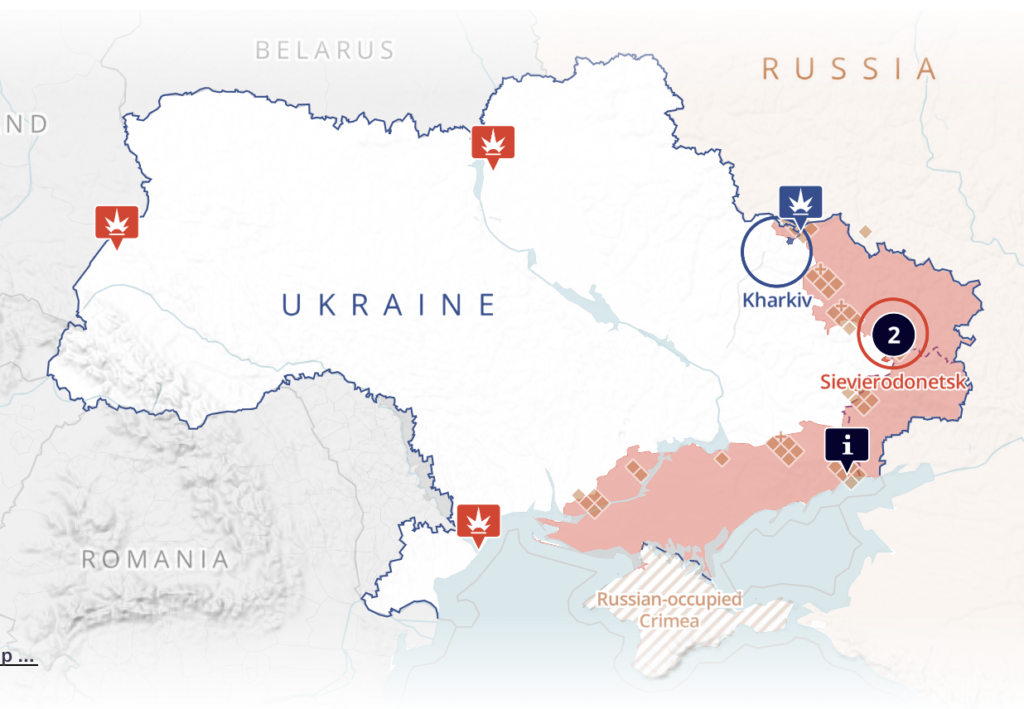

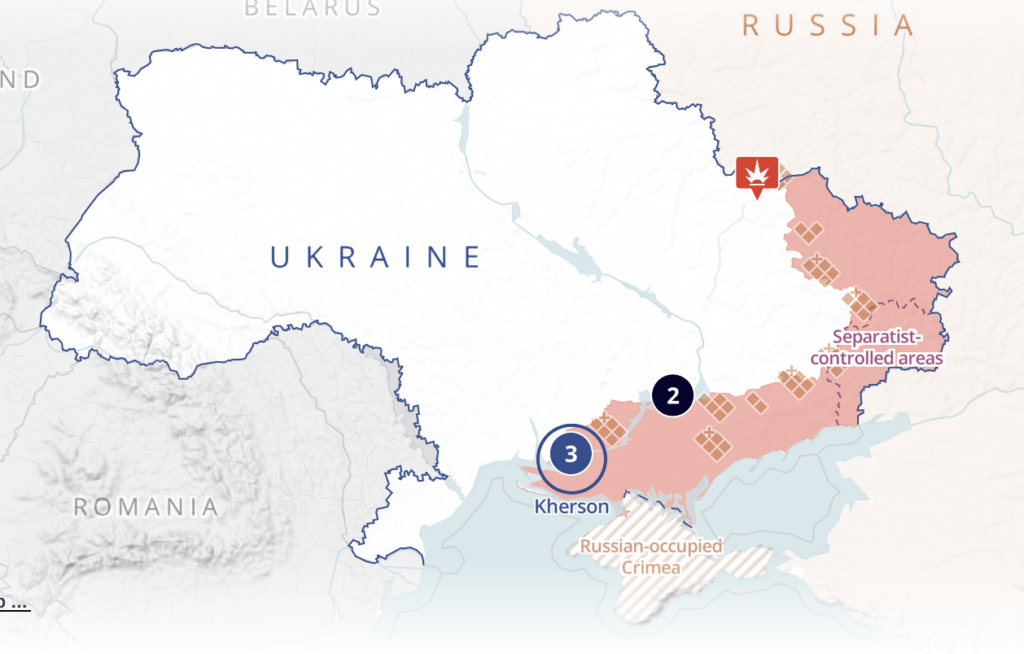

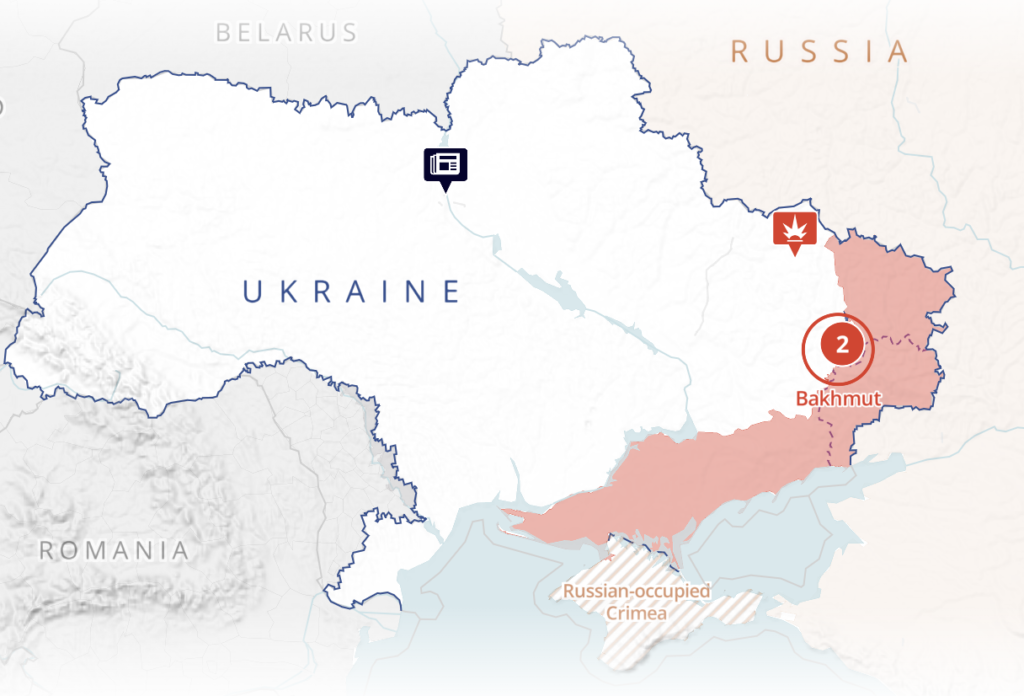

The process was popular and widespread. By 2020, “more than 10,000 Ukrainian villages, settlements and cities were amalgamated into 1470 new hromadas now enjoying considerable autonomy over local affairs.”

Arends et al show that areas with and without hromadas started with similar levels of trust in local and national government, but the ones that created hromadas saw substantial increases in trust for local (but not national) government. This empirical evidence is strongly suggestive that the reform caused trust to rise.

Here are a few reflections based on theory and studies from other countries.

First, I don’t read the paper as a general argument for decentralization, per se. Independent Ukraine had inherited a highly centralized system from the Soviet Union, and it was wise to moderate that by strengthening the local layer. The study does not imply that more power should necessarily be devolved to localities if they are already strong.

More important, I suspect, was the way the reform was designed. Contiguous communities were permitted to assemble themselves voluntarily into hromadas. This was a bottom-up process, requiring substantial agreement at the local level. One advantage was avoiding corruption: politicians and bureaucrats could not extract benefits by deciding which new local units to create or by conferring autonomy on favored local leaders. Another advantage was civic experience. Quite a few local stakeholders had to come together to negotiate and present each plan for a new hromada. They would later be able to use their network-ties, deliberative experience, and confidence for other purposes.

Second, trust in government is not intrinsically desirable. People should distrust bad governments. Some have argued that “trust” is not quite the right word for an attitude toward the state, which should rather inspire “confidence” if it functions well.

But we have survey data on trust, and the authors make good use of it to support a valuable empirical case. Still, the really interesting question is whether governance improved as a result of the reform. For example, did corruption fall? Trustful opinions may indicate improvement, because citizens are well placed to assess government, but I think the accuracy of their opinions deserves further attention.

At the same time, trust in government is often found to be a component of the construct labeled “social capital.” And social capital is a resource that communities can use to address problems–including corruption. But although trust in government is empirically a component of social capital (meaning that it correlates with the other components), it doesn’t suffice. It would be interesting to know whether Ukrainians in hromadas also developed other aspects of social capital, such as habits of participating in discussions and meetings and helping each other voluntarily.

Reference: Helge Arends, Tymofii Brik, Benedikt Herrmann, Felix Roesel,

Decentralization and trust in government: Quasi-experimental evidence from Ukraine,

Journal of Comparative Economics, 2023. See also: two approaches to social capital: Bourdieu vs. the American literature; social movements depend on social capital (but you can make your own); civilian resistance in Ukraine, revisited.