My remarks last week at a small conference on “Tolerance, Citizenship, and the Open Society” at the Tisch College of Civic Life …

We human beings did not evolve to take a broad view of justice, to collect information from diverse sources, to reason impartially, and to be responsive to other people who differ from us. These acts do not come naturally to us.

But we are capable of building prosthetics. For instance, we did not evolve with the skill to tell time precisely, which is now useful for coordinating behavior in mass societies. So we wear wristwatches, hang clocks on our walls, and display the current time on most of our electronic devices. A clock or a watch is a prosthetic device that extends our natural capacities.

An invention (in this case, a clock) will not suffice on its own. Many people must use it. That requires some kind of system that creates incentives or requirements for producing the devices and using them widely. A market with supply and demand can work; so can a state mandate. Either one is an institution.

We have created institutions that extend our ability to deliberate about justice. An example was the metropolitan daily newspaper from ca. 1910 to ca. 1990. Always very far from perfect, it nevertheless delivered important, mind-broadening information to about 80% of Americans every day in the year 1970. They (and advertisers) paid for the local press because it also provided sports, classified ads, comics, and whole package of goods–but with the most important news on the front cover, where it could not be missed.

A university is another institution that supports inquiry and discussion about important matters. It is more complex than a newspaper. Its revenues may include tuition, government aid, grants, gifts, intellectual property transfers, and clinical fees, among other sources. The goods it produces include skills and knowledge of value to each learner; virtues and skills that have public value; the pure public goods of basic knowledge and culture; monetizable forms of knowledge, such as patents; services, such as meals, art exhibitions, and clinical care; and credentials and entry to the middle class.

The skeptical view of such institutions is that their underlying economic motivations determine the ideas and discussions that they support. For example, newspapers are owned by tycoons or faceless corporations that just want to maximize profits. Universities sell social stratification and individual advancement. This analysis always merits attention and explains some of the phenomena. But it is one-sided, because these institutions are also the result of human artisanship–of people creating the means to sustain better thinking at a large scale.

For instance, the metropolitan daily newspaper can be interpreted as the product of the media industry, but it should also be seen as the product of the press. Traditional newspapers tried to distinguish the two by separating the newsroom from the publisher’s suite, but those subsystems were connected. For instance, plenty of publishers were former shoe-leather reporters. Their motives were mixed. That is good because mixed motives produce scalable public goods.

Too simple a theory would yield two predictions about newspapers that both proved incorrect. In 1900, you might predict that millions of people would never spend their own money voluntarily to purchase relatively impartial and challenging daily news. But they did–in part because they were also buying comics and box scores. In 1970, you might predict that we would always have a press, because it meets a social need. But the press has collapsed (half as many people work as reporters today compared to ten years ago) because the Internet has killed its business model.

As with other forms of artisanship, nothing is for certain. Ingenuity, commitment, and perseverance are required. The institutional structures that support broadened understanding depend on intentional work.

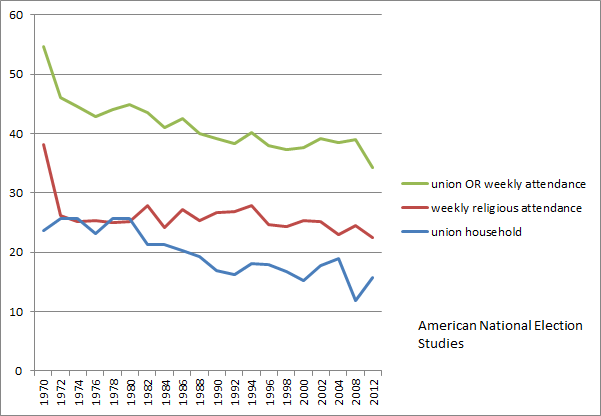

The results are always flawed. The recent scandals with college admissions just bring home the flaws of universities, for instance. We should have a free, open, informed, and consequential discussion about how to improve them. But no discussion can occur outside of a viable forum that depends on an institution. We don’t spontaneously gather to discuss; the discussion always happens in a university or a school, an op-ed page of a privately-owned newspaper, Facebook, a union hall, a church basement, a party convention, the state legislature–somewhere that draws resources and assembles users.

These institutions then structure and limit the discussion. There is no view from nowhere, only a permanent struggle to discuss as wisely as we can in various forums. We don’t create these forums deliberatively; most of them arise as the result of accident, power, or leadership. Because they are all flawed and limited, it is essential to have many of them, with diverse forms, competing and checking one another.

This is a “civic” perspective because it emphasizes our ability to shape the world of discourse through artisanship. And it broadens our attention so that we consider not only the rules for speech within an institution (e.g., campus speech codes) but also–and usually more importantly–the underpinnings of the institution itself.

See also a civic approach to free speech; Sinclair and Bezos: media ownership and media bias; don’t let the behavioral revolution make you fatalistic; prospects for civic media after 2016; China teaches the value of political pluralism; polycentricity: the case for a (very) mixed economy.