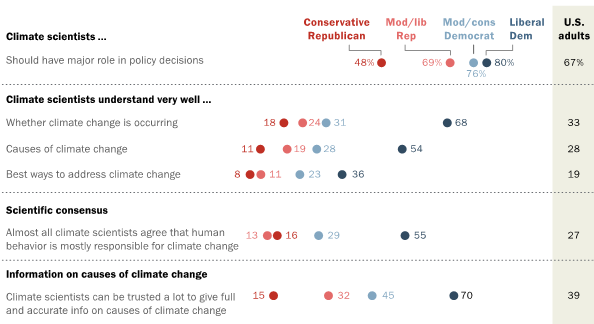

According to Pew’s new survey, only about one third of Americans care “a great deal” about climate change. That might be a matter of values: some citizens may set a higher priority on liberty or growth than on environmental protection, or they may not trust the government plus scientists to protect the climate.

But the public is also divided on a key matter of fact. In reality, there is near-universal scientific consensus that humans cause global warming, but only 27% of Americans perceive that consensus, including just over half of liberal Democrats.

If I thought that scientists were divided on the basic question of whether humans cause climate change, I would be much less confident that the problem is worth combating.

Two fairly obvious but crucial lessons:

- Giving an impression that a topic is contested is a great way to sew doubts about it. Once just a few people who claim expertise criticize the mainstream scholarly view, the issue looks debatable. Then everyone has permission to be skeptical.

- Scientists must take more responsibility for how their work is communicated, debated, received, and used by the public. There’s not much point to specific studies of climate change if a large majority of the public remains unconvinced about the basic problem. If the traditional division of labor–scientists conduct research; reporters cover it–ever worked, it doesn’t work now. Scientists and their institutions (including universities) must develop better ways of engaging in public life.

See also Five Strategies to Revive Civic Communication; science, democracy, and civic life.