Citizens experience the state in the form of people–teachers, social workers, police officers, nurses and doctors. These may be public employees or just subsidized by public funds, as when doctors get reimbursed by Medicare or professors get some of their salary from federal financial aid and grants. They help, serve, and protect; they also advise, cajole, assess and select, and discipline.

If we expand distributive justice (taxing richer people and spending the money on “government”), then relatively needy people will be confronted with human representatives of the state. These interactions will be friction points, sites of cultural conflict and resistance.

This is a well-known problem that has been discussed for a century. Traditionally, it has a strong class dimension: the state sends mostly college-educated people to both help and discipline working-class people. The state represents norms and ways of life embraced by the dominant social class. (I think this was even the case in the USSR.) In the US, the friction also has a racial dimension, even though white people have always been recipients of government support and surveillance in the US.

I think four strategies have often been proposed to reduce the friction:

- Make the state more demographically representative of the people it relates to. For instance, work to enhance the racial diversity of public school teachers, especially when their students are people of color.

- Design programs and laws–also train the “street-level bureaucrats” who deliver services–to minimize unnecessary moral superiority, reduce patronizing attitudes, and shift the balance to helping people versus disciplining them. For instance, educators are taught to be sensitive to their students’ backgrounds; social workers have norms against being judgmental.

- Organize or train the recipients of government services to stand up for their own rights and values.

- Expand cash transfers and other detached forms of redistribution that don’t involve monitoring and changing behavior (as education, policing, public health, and social work do).

None of these strategies has ever been fully successful. But we now see a new dynamic. A significant segment of the population identifies strongly as middle class and culturally mainstream. These are white, Christian people who may have attended college (often without completing BA degrees) and who may own small businesses or work in white-collar settings. They live in smaller towns, exurbs, and rural settings that represent a vision of respectability.

Traditionally, they identified with the state, particularly since they were very well represented in Congress, the state legislatures, and the military. Their typical question was whether or not to spend money on the government, which might waste their tax dollars but might also protect their national security, might genuinely help them without a lot of lecturing (think of agricultural extension workers or locally-controlled public schools), and would discipline other people.

Now this class—white, non-urban, Christian, and petit-bourgeois rather than working class–is in trouble. Obesity, opioid abuse, and suicide are rising to the point that their life-expediencies are falling. In some cases, their communities are losing population. Their traditional economic roles are in peril, and they’re told that their children must live and learn differently to retain their class position.

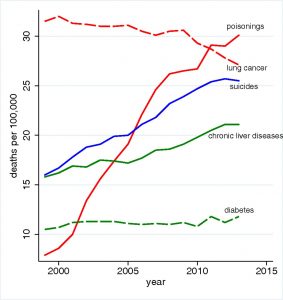

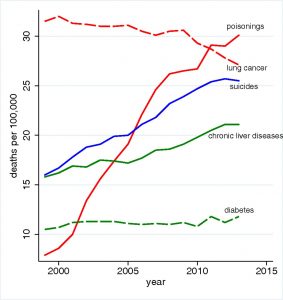

“Mortality by Cause for White Non-Hispanics Ages 45–54,” from Anne Case & Angus Deaton, PNAS December 8, 2015 112 (49)

The very bad trends depicted in this figure are concentrated among white people without college experience, but those with some college show increasing mortality. It’s only people with BAs or more who have escaped that pattern.

The state arrives to tell them to eat different foods, not to smoke, to raise their children differently. It may seem that the state disagrees with the messages that they hear in church, which they attend to live good lives. The state tells them to send their kids to the state university if they want to stay in the middle class. Their taxes and tuition dollars will pay for people who relate to them as the state has traditionally related to the poor and working class. Professors and student-affairs workers will steer their kids into a new culture that the coastal bourgeoisie has created. From the same universities come the k-12 teachers, nurses, and others who lecture them back in their own communities about food and exercise and carbon emissions. (Here I am indebted to Kathy Cramer, among others.)

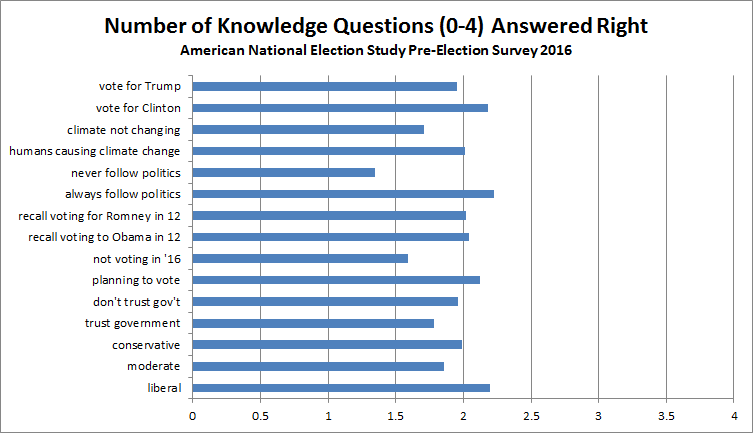

When asked whether the government should “do more” (1 on the scale below) or “is trying to do too many things that should be left to individuals and private business” (5 on the scale), white men have traditionally tilted against government. However, they caught up with white women in their support for government between 2014 and 2016, perhaps because they needed it more. We don’t have 2018 data yet, but we know they voted for Trump that year. This is consistent with needing government but not liking it.

The conflict between petit-bourgeois white people and the state is gendered, because many of the front-line representatives of the government are female, and many of the people with the most counter-normative behavior are men. The conflict is also racial in two respects. First, white, middle class people traditionally distinguished themselves from Americans who needed government aid and guidance, whom they viewed disproportionately as people of color; but that distinction is erased if the middle class also needs help. Second, representatives of the state–especially those who appear on TV–look at least somewhat more racially diverse than white communities do. At the very top of the state structure for eight years was a Black man.

I think these tensions are at the heart of current US politics. Focusing on them challenges both the “economic insecurity” and the “racial resentment” explanations of the 2016 election and its aftermath. A somewhat different premise is that lower-middle-class rural and exurban white Americans are now experiencing the state roughly as poor urban people are used to experiencing it. They need it but don’t like it, because it is always telling them they must change.

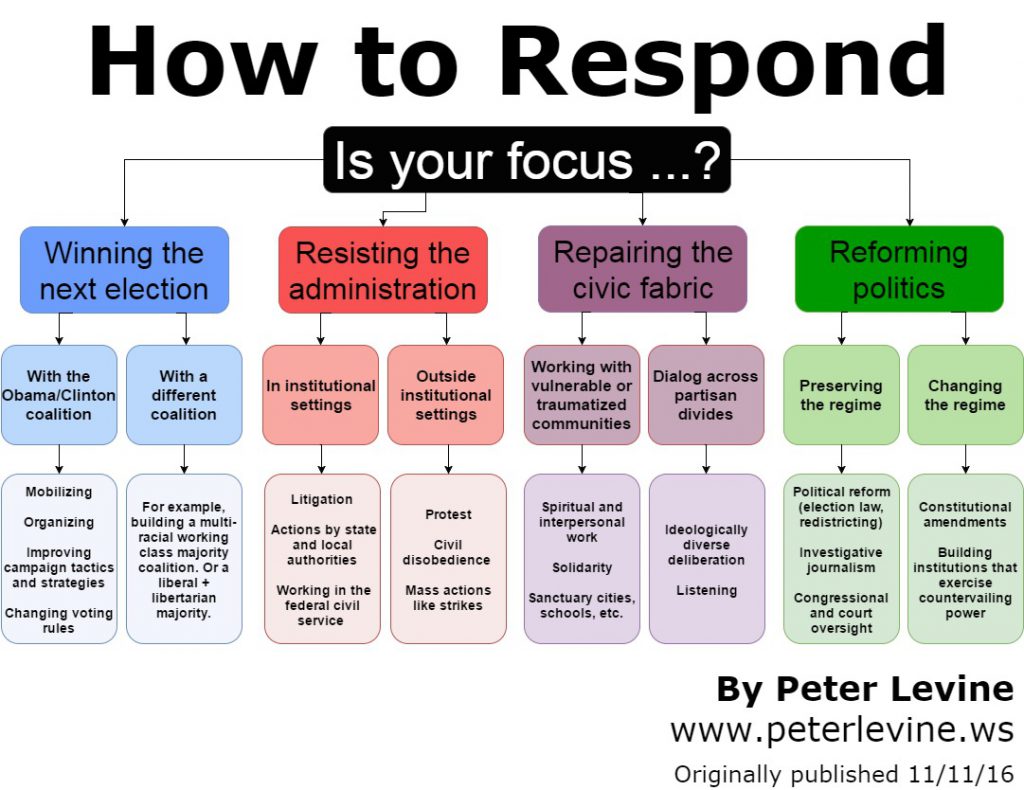

I’m not saying that most of them are responding appropriately or wisely, but we might want to dust off our tools for repairing the welfare state: make sure the government employs people who talk and look like those it affects, train them for sensitivity, organize those most affected by the state to push back, and try to shift to cash redistribution instead of invasive behavior-modification.

See also: why the white working class must organize; responding to the deep story of Trump voters; what do the Democrats offer the working class?