In public debates about issues and problems, we typically consider institutions in two ways. On the one hand, we discuss their explicit purposes and missions, as reflected in the laws that create and govern them or (if they are autonomous) their mission statements and express goals. We ask whether these purposes are good and, if not, how we should change them. On the other hand, we discuss the institutions’ outcomes: what they actually achieve.

For instance, in public debates about public schools, we debate what they explicitly strive for (producing citizens? boosting the economy?) and what they really accomplish in terms of outcomes for students.

We are then frustrated because institutions do not seem to produce their intended outcomes, nor do reforms move them in the intended directions. This may be because of a set of well-known phenomena:

- Path-dependence: Once an institution has developed in a certain way, shifting it is expensive and difficult.

- Principal/agent problems: People in institutions have their own interests and agendas (which need not always be selfish); and there is a gap between their assigned roles and their actual goals.

- Institutional isomorphism: Even when institutions are set up to be self-governing, they come to resemble each other. Witness the striking similarities among America’s 50 state governments or more than 5,000 colleges and universities.

- Rent-seeking: People within existing institutions often extract goods from others just by virtue of their positions. Economists call these payments “rents.”

- Bounded rationality: The individuals who operate within institutions have limited information about relevant topics, including the rest of their own institution. Information is costly, and it’s rational not to collect too much.

- Voting paradoxes: No system for aggregating individual choices by voting yields consistently defensible results.

- The Iron Law of Oligarchy: Even in organizations explicitly devoted to egalitarian democracy (the classic examples are socialist parties), a few highly-committed and tightly networked leaders almost always rule.

- Epistemic Injustice: Knowledge is produced by institutions–not (for the most part) by individuals–and institutions favor knowledge that is in their own interests.

New Institutionalists emphasize and explore these phenomena. Their findings suggest either that citizens (meaning everyone who deliberates about how to improve the social world) should become much more attentive to these features of institutions, or else that we are incapable of social analysis because it is just too hard for millions of people to deconstruct millions of institutions. In the latter case, we should abandon ambitious theories of public deliberation and democracy.

New Institutionalism is heterogeneous. For one thing, it is ideologically diverse. Scholars who write about rent-seeking and voting paradoxes are often coded as right-wing, and sometimes they attribute rents mainly to governmental entities as opposed to markets. (Still, those of us on the left should take this issue seriously if we want to design governments that work for people). Scholars who write about Epistemic Injustice are often coded as left-wing; this idea emerged in feminism. The Iron Law of Oligarchy originated on the left, too, with Robert Michels.

New Institutionalism is diverse in other ways apart from ideology. For instance, the version that emerged from Rational Choice Theory is methodologically individualist. It models institutions as the result of interactions among individuals who have distinct goals and limited information. Some other versions of New Institutionalism are explicitly critical of methodological individualism. They attribute causal roles to institutions as opposed to individuals.

There is also a debate about determinism versus chance and choice. Historical institutionalists often emphasize the contingency of outcomes. Due to a random confluence of circumstances at a pivotal moment, an institution gets on a “path” that persists. In contrast, institutionalists who use rational-choice analysis often try to demonstrate that a given institution is in equilibrium, which implies that it almost had to take the form that it does.

Given this heterogeneity, we might begin to wonder whether New Institutionalism is a thing at all. Here is an alternative view: Institutions matter, but so do ideas, values, climates of opinion, identities, technologies, demographic changes, and biophysical feedback (e.g., climate change). Because many factors are relevant, there is often a moment when someone needs to say, “We have been neglecting institutions!” This person usually fails to find adequate resources in the “old” institutionalist authors: Weber, Veblen, Michels, et al. So she naturally calls herself a “New Institutionalist.”

In that case, New Institutionalism is not a movement or a phase in intellectual history. It is a recurrent stance or trope in debates since ca. 1900. As Elizabeth Sanders writes:

Attention to the development of institutions has fluctuated widely across disciplines, and over time. Its popularity has waxed and waned in response to events in the social/economic/political world and to the normal intradisciplinary conflicts of ideas and career paths. … Some classic works that analyze institutions in historical perspective have enjoyed a more or less continuous life on political science syllabi. Books by Max Weber, Maurice Duverger, Alexis de Tocqueville, John Locke, Woodrow Wilson, Robert McCloskey, and Samuel Beer are prominent examples.

Elizabeth Sanders, “Historical Institutionalism,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions (2008)

Still, a case can be made that we are in the midst (or perhaps the wake) of a New Institutionalist Movement. Sanders observes that classic theories of institutions were “increasingly sidelined … with the rise of behaviorism after the Second World War, particularly with the emergence of survey research and computer technology. …. However, after a hiatus of several decades, the study of institutions in historical perspective reemerged in political science in the 1970s, took on new, more analytical, epistemological characteristics, and flowered in the 1980s and 1990s. Why this reemergence?”

I’d give a slightly different answer from hers. I would note that several ideologies were influential from ca. 1945-1980. Here I don’t define an “ideology” as a form of invidious bias, nor as a mere basket of ideals. It is a more-or-less harmonious combination of ideals, causal theories, grand narratives, exemplary cases and models, and favored institutions. It makes sense of the world and motivates change, including positive change.

By that definition, liberalism, wealth-maximizing utilitarianism, democratic socialism, deliberative or participatory democracy, and Leninism were all ideologies. But none took sufficient account of the phenomena listed above. None was Institutionalist, in that sense. And all have been set back on their heels by the increasing strength and plausibility of Institutionalist research.

This my basis for claiming that New Institutionalism is a movement with consequences. Almost all of the ideological options available in 1968 or 1980 are less confident, less coherent, and less prominent today, thanks in significant measure to Institutionalist analysis conducted since then.

This account applies strongly to the stance that I grew up with: deliberative democracy. It originated in normative political philosophy plus small-scale voluntary experiments that succeeded in their own terms. It never attended enough to Institutionalism, and it now looks increasingly naive.

The main exception is classical liberalism/libertarianism. In the political domain, this ideology faces at least as much trouble as the others do. The libertarian-leaning (but never consistent) Republican Party has been taken over by authoritarian nationalists. However, in the intellectual domain–in the classroom–libertarianism has offered a coherent answer to New Institutionalism. It holds that all the flaws of institutions are worse in monopolistic state organizations than in markets. It can even explain why this insight is not more broadly understood: state schools and nonprofit colleges are run by rent-seekers who oppose libertarian ideas.

I dissent on several grounds (as do thoughtful classical liberals), but I’d still venture that classical liberals weathered New Institutionalism better than their rivals did, which explains a certain confidence in their ranks from ca. 1980-2008.

But now classical liberalism faces the same threat as all the other ideologies. The movement that is being called Populism (although I’d apply that word to other traditions, too) is perfectly calibrated for a world explained by New Institutionalism. Populism begins by denouncing all the institutions around us as corrupt because they unaccountably fail to generate their promised outcomes. It attributes this failure to the treason of elites: people well situated within existing institutions. It describes a homogeneous “us” (usually a racial or national group) that has been betrayed by “them,” the elites and foreigners. And it endorses a strong leader who fights for us against them. It dismisses specific institutional analyses as mere excuses and envisions a simple system that avoids all such Institutionalist problems. In this system, the authentic citizens constitute a unified majority; they select a leader in an occasional vote; and the leader rules.

In the face of this challenge, what are our options?

- We could embrace the right-wing authoritarian populism. That is morally repugnant. Also, it won’t actually work over the long run.

- We could ignore the findings of New Institutionalism and barrel ahead with an ideology like deliberative democracy or social democracy. I don’t think that’s smart.

- We could count on elites to address the flaws of the institutions they lead. I don’t think that will happen, not only because elites are untrustworthy but also because these flaws are hard to fix.

- We could beat the right-wing populists in other ways: by revealing their corruption, seizing on their missteps, or just running better candidates. This is important, but what happens after a Putin, an Orban, or a Trump?

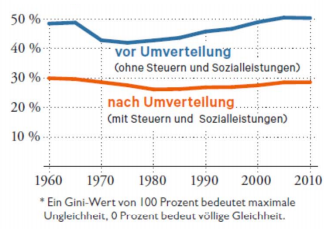

- We could re-engineer the institutions we care about by giving more attention to New Institutionalist insights. I think European social democrats have done so, to a degree. Social welfare programs in the Eurozone reflect concerns about path-dependence, feedback loops, principal/agent issues, etc. Deliberative democrats could, likewise, build deliberative institutions that take more account of such problems. This is a worthy approach but it requires compromises. For instance, social democratic systems may have to be less egalitarian to enlist the support of wealthy constituencies. And deliberative democratic forums may have to be made less democratic, for similar reasons.

- We could enlist a wider range of people than just “elites” to work on the problems of specific institutions. We could make the solutions democratic. That is valuable but a long and slow process.

- We could educate the public about the inner workings of institutions, their pathologies and solutions. That is important but hard.

I see our work in Civic Studies as a combination of the last two responses.

See also: teaching about institutions, in a prison; a template for analyzing an institution; decoding institutions; a different approach to human problems; fighting Trump’s populism with pluralist populism; separating populism from anti-intellectualism; against methodological individualism.

Now available for pre-ordering is Charles S. White (ed.),

Now available for pre-ordering is Charles S. White (ed.),