In a museum not far from our house, there is a painting entitled “Zen Saying” by the great teacher Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768). Author of the koan “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”, Hakuin “was the most influential Rinzai Master in Japanese history” (Kasulis 1981, p. 105), and Rinzai is one of the three traditions of Japanese Zen.

The label translates the calligraphed words as: “Verdant mountains usually walk, barren women give birth at night.” The label also explains that the character for “usual” or “normal” (tsune) is here elongated in an unusual way–indeed, to the very “limits of legibility.”*

When I try to think about verdant mountains walking, I can form inferences. For example: if verdant mountains walk, we’d better stay out of their way! I cannot picture them walking without resorting to a cartoonish image. This is a limitation of my imagination, of language, or of the possible.

I can imagine that Hakuin–after decades of practice–had a different experience from mine when he thought of walking mountains and barren women giving birth. I can picture him having that experience without sharing it.

(By the way, he might equally have seen statements such as “The self exists” and “There is no self” as senseless paradoxes.)

I cannot read Hakuin’s brushstrokes. I could, however, learn to read Japanese calligraphy, and I already know (roughly) what this text means. The characters are across a border of understanding from me, yet I can know what lies over there and can even shift the border by learning more from scholars and intermediaries.

I cannot feel what it was like to be the artist who painted this image, but I can learn many facts about his life, his genre, the koan he represents here, the tradition of koans, and his context. Again, Hakuin stands across a border, but I can indefinitely continue learning about what is on his side.

Right now, I am looking at a photograph of the painting, having recently seen the original. My mental state is reasonably calm but perhaps a bit distracted, since I am also typing. I know that I could see the same image while anxious or bored, and the whole experience would be different. I could even deliberately induce a state of anxiety. Then I would know that I had experienced the image while I was calm, but I would no longer be able to feel it the same way.

In short, there is a border around my current state of mind. I know what lies beyond it and can say (roughly) how it feels over there, but I cannot feel it now. I do know that the world for me always has a certain mood, which can change. In that sense, I know that my condition is temporal.

Expanding the scale of time, I can recall (sometimes vividly) what it felt like to be a child or a young parent with a child in arms. But those are memories rather than experiences. There is a border around my identity as a middle-aged person. I can see over it but cannot cross it.

I can imagine the permanent end of my own consciousness. But experiences turn instantly into memories, and not so with death. There is a border around the whole of a life. We can know what the world will be like without ourselves in it but cannot feel that absence. Hakuin experienced the end of his consciousness and left something for us that he can no longer know.

I am sitting and typing next to my dog. We each know and care a lot about the other. But Luca has no idea about Japanese Buddhist calligraphy, not even enough to form questions that are beyond his ken. He doesn’t know that he doesn’t know. I understand barely enough about Zen that I do know some of what I don’t know, but my dog’s example shows that there can easily be things entirely beyond any being’s capacity to grasp.

The Japanese word kyogai is important in Zen practice. It is often translated as “consciousness.” It turns out that it literally means “boundary” or “bounded place,” and it derives originally from the Sanskrit word visayah, in the sense of a pasture that has a boundary.

Think of an animal grazing in a space surrounded by hedges. Or think of Hakuin, with his specific language and mood, writing about verdant mountains that walk. The mountains are outside his pasture, and he is outside mine.

Mumon Yamada (1900-1988) taught:

This thing called kyogai is an individual thing. Only a sparrow can understand the kyogai of a sparrow. Only a hen can understand the kyogai of a hen and only another fish can understand the kyogai of a fish. In this cold weather, perhaps you are feeling sorry for the fish, poor thing, for it has to live in the freezing water. But don’t make the mistake of thinking it would be better off if you put it in warm water; that would kill it. You are a human and there is no way you can understand the kyogai of a fish (in Hori 2000)

This is not precisely true. We can understand a vast amount about the fish, including its ideal water temperature and details about its sensory organs and neurology. There is a sense in which we can understand the kyogai of the fish and the fish cannot. It presumably has no grasp of the category of kyogai (or to draw from a different tradition, Umwelt). However, it is correct that we can never know how it feels to be a fish. We can’t even feel as we ourselves do in a different mood. And who knows what kyogai we cannot even imagine?

Victor Sogen Hori adds:

Kyogai can be said to change and develop, for it is a product of human effort. Thus one can say “His kyogai is still unripe” (Mada kyogai ga mijuku) or “His kyogai is still shallow” (Mada kyogai ga asai), implying that even though the monk has been working at overcoming his indecision, or fear, or pride, he still shows traces of self-consciousness. Finally, kyogai bears the quite personal imprint of the particular individual. One person’s way of acting in a fire drill, cooking in the kitchen, carrying on the tasks of daily life may be energetic and impassioned; another may do the same tasks coolly and methodically. Yet each may in his own fashion be narikitta in the way he acts. Thus one can say of monk Daijo’s way of performing some task, “That is typically Daijo kyogai.” (Hori 2000, p. 293).

If we can change our kyogai, how should we go about that?

We can ignore the boundaries (including the boundary of death) and graze in our respective pastures. This may be wise.

We can explore our own pasture and its boundaries to come to understand it fully. That is what Kant meant by a “critique” of reason–not a criticism of it, but an analysis of its structure and limits.

We can interact with people who have crossed our own boundaries. I am fortunate that a painting from the hand of one of the most famous Zen masters is in my neighborhood. To study that painting is to observe someone from a different time and context–and specifically someone who wrote about things “whereof one cannot speak.” Hakuin wrote koans not for himself but to benefit others, living and not yet born.

And we can try to cross the boundaries. A koan is a tool for doing that. The painting by Hakuin represents a verbal koan in Japanese characters. It is also a physical object that can work as a koan.

Dogen (1200-1253) comments on the koan, “Who can hear insentient beings speak dharma?” He says:

Only the insentient know the dharma they speak of,

just as walls, grass, and trees know the spring.

Ordinary and sacred are not hemmed in by boundaries,

nor are mountains and rivers; sun, moon, or stars.

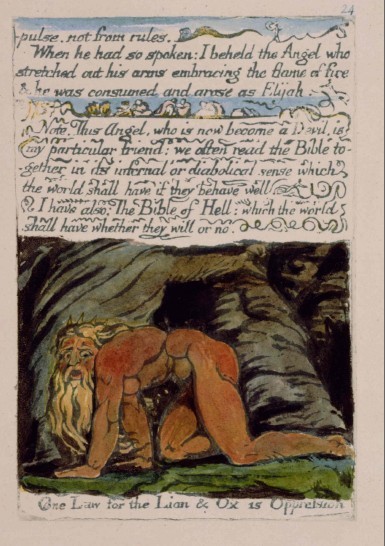

“Zen Saying” is an insentient object that hangs on the wall of the museum. During a few seconds more than 250 years ago, Hakuin took a stick of hardened soot and glue, ground it with water, dipped a brush into the mix, and spread some of the blackness downward across the paper to make a long, imperfectly straight, sometimes translucent line that is unmistakably a brushstroke. That line is a bit of earth, a thing. It depicts nothing, but it means “usual,” contributing to a sentence about something so unusual that we cannot envision it.*

The line is a trace of the act of a specific man who long ago became insentient soot himself. The other insentient things around this work look different in its presence, as–according to Heidegger–a Greek temple that stands on the earth and presents itself as the home of a god makes a world appear:

The luster and gleam of stone, glowing by grace of the sun, first makes manifest the light of the day, the breadth of the sky, the darkness of the night. The temple’s firm towering makes visible the space of air. The steadfastness of the work contrasts with the weaving of the flowing sea, and in its own repose brings out the latter’s turmoil. Trees and grass, eagle and bull, snake and cricket first enter into their contrasting shape and thus come to appear as that which they are (Heidegger 1964, pp. 669-70).

Standing in the presence of the “Zen Saying,” I sense my contrast with it and feel myself appearing as that which I am.

References: T.P. Kasulis, Zen Action, Zen Person (University Press of Hawaii, 1981); Victor Sogen Hori, “Koan and Kensho in the Rinzai Zen Curriculum,” in The Koan. Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism (2000); The Essential Dogen, edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi and Peter Lovitt (2013), p. 170; and Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” trans. Albert Hofstadter, in Philosophies of Art and Beauty, ed. Albert Hofstadter and Richard Kuhns (New York: The Modem Library, 1964). See also: thinking both sides of the limits of human cognition; ‘every thing that lives is holy’: Blake’s radical relativism; a Heideggerian meditation; nostalgia for now; Ito Jakuchu at the National Gallery; and on inhabiting earth with inaccessibly beautiful things

*I got that information from the label, but a friend tells me that the character that is so boldly elongated stands for “walk.”

The post Verdant mountains usually walk appeared first on Peter Levine.