Monthly Archives: February 2016

what the Sanders youth phenomenon means for the future

(En route from NYC to DC) Early reports from the New Hampshire exit polls suggest that Sen. Sanders won about 8 in 10 voters under 30. Follow CIRCLE tomorrow for exclusive estimates of the size of the youth turnout. That will be important for helping to sort out whether Sen. Sanders’ dominance so far is a sign of his appeal–or of Hillary Clinton’s weakness.

I drew the latter conclusion while talking about Iowa last week on WGBH’s Greater Boston show with Jim Braude. Here’s the video clip. He and the other guests were very excited about Sen. Sanders’ large lead among young voters, both in the Iowa results and the Nrw Hampshire polls. Although I should try to avoid the role of the graying curmudgeon, I drew attention to Hillary Clinton’s poor showing in Iowa. Less than 5,000 young people caucused for her in the whole state, which seems to me an alarming sign both for Democrats in November and for anyone who cares about youth participation.

Just to put my comments in a broader context, I do think that Sanders’ youthful following is important. True, only about 35,000 youth voted for Sanders in Iowa. That is about one percent of the state’s population, and it was favorable terrain for him. Still, thousands of young people are having formative experiences as activists on the American left through his campaign (even as others come up through Black Lives Matter or the Dreamers’ or Marriage Equality campaigns). We know from extensive research that such experiences leave lasting imprints. A classic work is Doug McAdam’s Freedom Summer. It’s amazing how many leading figures of the left went to Mississippi in 1964, and McAdam shows how that summer shaped them for decades to come. I suspect when we read the biographies of leading progressive activists in 2030, many will say they worked for the Vermont senator in the winter and spring of 2016.

In the short term, the American left will struggle if Hillary Clinton is elected president (as I expect her to, unless a Republican beats her in November). While a centrist Democrat holds the ramparts against a Republican House, Republican statehouses, and a conservative judiciary, people to the president’s left will face constant pressure to pipe down. Concretely, the organized left may face a shortage of money, paid positions, media attention, technological innovation, and other forms of capacity–much as I recall from the Bill Clinton years, when I myself was young.

This is not ground for despair. Young activists can find solutions. For some of them, experiences with the Sanders Campaign will prepare them for the next four or eight years. Their activism will help President Hillary Clinton to do a good job, because (as FDR said) leadership is deciding who to cave to. She’ll need some pressure from that side.

All of which is to say that the youth support for Sanders is a real phenomenon that is worth following and caring about. But if one is interested in who will win the 2016 presidential election, I am afraid the Sanders phenomenon is likely to be something of a footnote as the primary campaign moves to larger and more diverse states. In that context, the important question is whether Senator Clinton can improve her showing with youth, whom she will absolutely need to win in November.

Gender and Politics

Women, historically, can’t seem to get a fair shake.

For centuries, women in the west have been subjected to a sinner/saint duality. That is, any woman who fails to live up to an idealized construction of womanhood must automatically be relegated to the lowest depths of depravity – there is no middle ground, no subtly to society’s judgement of femininity.

As one author puts in examining this trend in Victorian literature, “When a woman deviated from the Victorian construction of the ideal woman, she was stigmatized and labelled. The fallen woman was viewed as a moral menace, a contagion.”

A contagion. For a woman, that’s how serious any momentary personal failing – or perceived failing – might be.

In modern times, this duality has haunted women seeking positions of leadership and power. Female leaders must be confident but not assertive; nurturing but not emotional, dedicated mothers and dedicated employees. In short, women must fulfill masculine ideals of leadership without losing an ounce of idealized femininity.

This is not challenging: it is downright impossible.

Victoria Woodhull was the first woman in the U.S. to run for president. She ran in 1872, a good 50 years before U.S. women won the right to vote. Woodhull, who was married twice and held the radical notion that women ought to have the right to marry and divorce as they choose, was widely accused of being a prostitute.

No doubt, this was simply a term for a woman who spoke her mind.

Ultimately, Woodhull spent election night in jail, arrested with her husband and sister for “publishing an obscene newspaper.”

“Obscene” in this case meant highlighting the “sexual double-standard between men and women.”

That is the history that has led us here. To the second president run of the most viable female candidate our nation has ever seen.

(I would, of course, be remiss here if I didn’t mention the dozens of other impressive women who have run for this office.)

And make no mistake, Hillary Clinton has suffered from the same old-fashioned double standards which have plagued women for generations. But solidarity on that issue is not enough to determine a vote.

When Clinton entered the 2008 race her campaign miscalculated a core fact about her base. Women, she expected, would be with her. Women of all ages.

This was not true.

As Abraham Unger, Assistant Professor of Government & Politics at Wagner College, wrote of the 2008 primaries, “Senior women, who came of age during the pioneering period of the feminist movement, did vote for Clinton, while younger women were drawn to Obama. Women in the middle were split between the two.”

With Barack Obama running a historic campaign of his own, it became impossible to disambiguate the effects of race, gender, age, and class in determining a person’s political affiliation. A vote for someone other than Clinton wasn’t a vote against womanhood; it was a vote for something more.

Women, it seemed, would have to wait.

When Clinton launched her current bid for the White House, I wondered what tactics she would take to close the age gap. Surely, she had learned that young women weren’t unquestionably in her court.

And yet here we are – watching the surprising rise of an old, white man – matching Clinton beat for beat; capturing the hearts, minds, and votes of younger voters.

Again, we see young people – men and women alike – drawn to the upstart, outsider candidate. The one who encourages us towards hope; towards radical change of a broken system.

Clinton supporters are not impressed.

I’ve been floored by some recent comments. Gloria Steinem said that young women supported Sanders because they were thinking “Where are the boys?” Meanwhile, Madeline Albright warns that “there’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other.”

Is this the feminism we are supposed to be defending?

To be clear, we’d do well to be mindful of the subtle impact of sexism. Anyone who doesn’t support Clinton should do some careful thinking about their reasons and motivation, watching out for the impulsive and flippant urge to deride her voice, pantsuits, or (lack of) emotions.

At least we can take comfort in the scrutiny of Marco Rubio’s boots.

But let’s never use gender as litmus test – one way or the other.

The truth, I suppose, is that feminism is changing.

I can’t truly appreciate the feminism of women who are older than me. Women who were mistreated or outright fired explicitly because of their gender; much less the feminism of women who were pushed into loveless marriages, who were forced upon by their husbands and who had no voice or recourse in the matter.

We should not forget the fight of Victoria Woodhull, nor of countless other women who have pushed relentlessly towards gender parity. There has been much to fight for, and the fight still goes on.

But right now, right here in this moment, thankful for all the women who have come before me – I am not looking for boys nor concerned about hell. I am simply looking for the candidate who most closely speaks to my diverse political concerns.

In this race, for me, it happens that person is man. But how lucky for me – I have a vote in the matter.

And no one can take that away.

Seeking Nominations for Inaugural Civilution Awards by 2/14

We want to encourage NCDD members to consider submitting nominations for the inaugural Civilution Awards, hosted by the Bridge Alliance – an NCDD member organization. NCDD was one of the founding members of the Alliance because we respect their efforts to foster ” transpartisan” politics in the US, and the Civilution Awards are a way to recognize those leading the way. We’d love to see an NCDDer win this year, so be sure to submit your nominations before the deadline on Feb. 14th! Learn more about the Civilution Awards in the Bridge Alliance announcement below, or find the original here.

Civilution Awards

Civilution Awards

Get out your tux. Your designer gown. Start preparing your acceptance speech.

We’ll see you on the Red, White, and Blue carpet!

The inaugural Bridge Alliance Civilution Awards, presented by the “Academy of Civility and Bridge-Building Arts & Sciences,” will honor one individual and one organization for truly embodying the Civilution Declaration and exemplifying best bridge-building practices.

Civilution Declaration

- Engage in respectful dialogue with others, even if we disagree.

- Seek creative problem solving with others.

- Support elected officials and leaders who work together to address and solve our nation’s challenges.

All nominees – both individuals and organizations – will be considered based on the following core principles and criteria:

- Collaborative partnership: Excellence in collaboration with other individuals or organizations, finding creative ways to work together.

- Innovative solutions putting country before party: Creatively addressing even the most challenging of problems across political divides or special interests.

- Display of curiosity and inquisitiveness in political conversations: Demonstration of openness and curiosity, display of respect and civility.

Nominations for this prestigious award will be accepted February 1st through February 14th with a culminating virtual awards ceremony to recognize excellence in our field on February 28, 2016.

Judges will review submission, media stories, blogs and websites. Judges are volunteers and staff of the Bridge Alliance.

Please include contact information for your nominee. If you would like to make more than one nomination, email info@bridgealliance.us.

Selim Berker on moral coherence

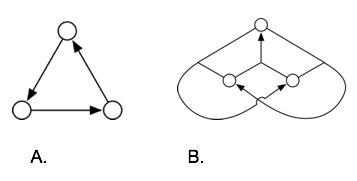

In “Coherentism via Graphs,”[i] Selim Berker begins to work out a theory of the coherence of a person’s beliefs in terms of its network properties. Consider these two diagrams (A and B) borrowed from his article, both of which depict the beliefs that an individual holds at a given time. If one beliefs supports another, they are linked with an arrow.

Both diagrams show an individual holding three connected and mutually consistent beliefs. Thus traditional methods of measuring coherence can’t differentiate between these two structures. However, Graph A is pretty obviously problematic. It involves an infinite regress—or what has been called, since ancient times, “circular reasoning.” Graph B is far more persuasive. If someone holds beliefs that are connected as in B, the result looks like a meaningfully coherent view. If you find coherence relevant to justification, then you will have a reason to think that the beliefs in B are justified—a reason that is absent in A.

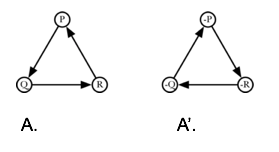

Berker also proposes a subtler but more decisive reason that B is better than A. Below I show A again, now with the component beliefs labeled as P, Q, and R. If the law of contraposition holds, than A implies another graph, A’, that is its exact opposite. A’ includes beliefs -P, -Q, and -R, and the arrows point in the reverse direction.

But that means that if belief P is justified because it is part of a coherent system of beliefs, then the same must be true of -P, which is absurd.[ii]

The overall point is that coherence is a property of the network structure of beliefs. That should be interesting to coherentists, who argue that what justifies any given belief just is its place in a coherent system. But it should also be interesting to foundationalists, who believe that some beliefs are justified independently of their relations to other ideas. Foundationalists still recognize that many, if not most, of our beliefs are justified by how they are connected to other beliefs. Thus, even though they believe in foundations, they still need an account of what makes a worldview coherent.

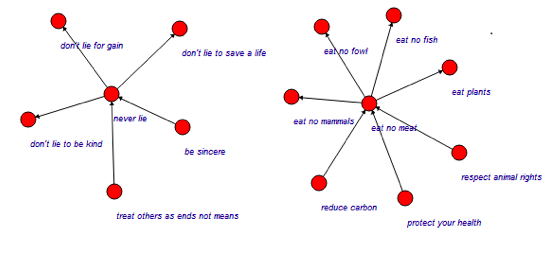

I have been developing a similar view, with a narrower application to moral thought (and without Berker’s deep grasp of current epistemology). I am motivated, first, by the sense that what makes a moral worldview impressively coherent cannot be seen without diagramming its whole structure. Imagine, for instance, a person who holds two major moral beliefs: “Never lie” and “Do not eat meat.” Assume that this person has not found or seen any particular connection between these two main ideas.

His or her set of maxims is perfectly consistent: there is no contradiction between any two nodes. And every idea has a connection to another. But if we wanted to judge the coherence of this worldview, we would not be satisfied with knowing the proportion of the components that were consistent and directly connected. It would matter that the person holds two separate clusters of ideas—two hubs with spokes. This person’s network is fairly coherent insofar as it is organized into clusters rather than being completely scattered; but it would be more coherent if the two clusters interconnected via large integrating ideas. You can’t see the problem without diagramming the structure.

I also have another motivation for wanting to explore moral worldviews and political ideologies as networks of beliefs. In moral philosophy and political theory, constructed systems are very prominent. Although diverse in many respects, such systems share the feature that they could be diagrammed neatly and parsimoniously. In utilitarianism, the principle of utility is the hub, and every valid moral judgment is a spoke. That theory is so simple that to diagram it would be trivial. Kantianism centers on several connected principles, and Aristotelian, Thomist, and Marxist views are perhaps more complicated still. But in every case, a network diagram of the theory would be organized and regular enough that the whole could be conveyed concisely in words.

In contrast, my own moral worldview has accumulated over nearly half century as I have taken aboard various moral ideas that I’ve found intuitive (or even compelling) and have noticed connections among them. My network is now very large and not terribly well organized. A narrative description of it would have to be lengthy and rambling. Many of my moral beliefs are nowhere near each other in a network that sprawls widely and clusters around many centers.

I suspect this condition is fairly typical. No doubt, individuals differ in how large, how complex, and how organized their moral worldviews have become, but a truly organized structure is rare. (I have asked a total of about 60 students and colleagues to diagram their own views, and only one of the 60 gave me a network that could be concisely summarized.) That means that such constructed systems as Kantianism and utilitarianism are remote from most people’s moral psychology.

Further, I think that having a loosely organized but large and connected network is a sign of moral maturity. It is a Good Thing. That is obviously a substantive moral judgment, not a self-evident proposition. It arises from a certain view of liberalism that would take me more than a blog post to elucidate. But the essential principle is that we ought to be responsive to other people’s moral experiences.

Berker includes experiences as well as beliefs in his network-diagrams of people’s worldviews.[iii] In science, it should not matter who has the experience. An experience of a natural phenomenon is supposed to be replicable; you, too, can climb the Leaning Tower and repeat Galileo’s experiment. But in the moral domain, experience is not replicable or subject-neutral in the same way. Since I am a man, I cannot experience having been a woman my whole life so far. Thus vicarious experiences are essential to moral development.

If we are responsive, we will accumulate sprawling and random-looking networks of moral beliefs as we interact with diverse other people. These networks can be usefully analyzed with the techniques developed for analyzing large biological and social networks. It will be illuminating to look for clusters and gaps and for nodes that are more central than average in the structure as a whole. The coherence of such a network is not a matter of the proportion of the beliefs that are consistent with each other. Its coherence can better be evaluated with the kinds of metrics we use to assess the size, connectedness, density, centralization, and clustering of the complex networks that accumulate in nature.

On the other hand, if someone adopts a moral view that could be diagrammed as a simple, organized structure, he has not been responsive to others so far and he will be hard pressed to incorporate their experiences in the future. At the extreme, his simple graph is a sign of fanaticism.

See also: envisioning morality as a network; it’s not just what you think, but how your thoughts are organized; Stanley Cavell: morality as one way of living well; and ethical reasoning as a scale-free network (my first thoughts along these lines, from 2009).

Notes

[i] Berker, S. (2015), Coherentism via Graphs. Philosophical Issues, 25: 322–352. doi: 10.1111/phis.12052

[ii] “Coherence, we have been assuming, is a matter of the structure of support among a subject’s beliefs, experiences, and other justificatorily-relevant mental states at a given time.” But we can use directed hypergraphs (in mathematics, networks in which any of the nodes can be connected to any number of the other nodes by means of arrows) to represent all of those support relations. That is, we use directed hypergraphs to represent all of the relations that have a bearing on coherence. It follows that coherence is itself expressible as a graph-theoretic property of our directed hypergraphs (p. 339).

[iii] “Many theorists hold that a subject’s perceptual experiences are justificatorily relevant (in these sense that they either partially or entirely make it the case that the subject is justified in believing something).”

Listening for, and Finding, a Public Voice (Connections 2015)

The four-page article, Listening for, and Finding, a Public Voice by Bob Daley was published Fall 2015 in Kettering Foundation‘s annual newsletter, “Connections 2015 – Our History: Journeys in KF Research”.

The article describes how the design of deliberative democracy by David Mathews, president of Kettering Foundation, and Daniel Yankelovich, president of Public Agenda; sought to address what it meant to have “a public voice”. From this inquiry came a series of deliberative forums around some of the more important current issues, and the results were then shared with policymakers. Kettering Foundation created, A Public Voice, a nation-wide broadcast that would act as the annual report of these deliberative forums, which first aired April 1991 and continues to today. Below is an excerpt from the article. Connections 2015 is available for free PDF download on Kettering’s site here.

From the article…

The question was: If the public doesn’t offer infallible wisdom for policymakers, what does it offer? The exchange between Henry and Cheney marked the beginning of the foundation’s inquiry into a public voice—not, mind you, the public voice, but a public voice—that continues today.

The question was: If the public doesn’t offer infallible wisdom for policymakers, what does it offer? The exchange between Henry and Cheney marked the beginning of the foundation’s inquiry into a public voice—not, mind you, the public voice, but a public voice—that continues today.

In his 2012 book, Voice and Judgment: The Practice of Public Politics, Kettering Foundation senior associate Bob Kingston said researchers wanted “to learn more clearly how the public might find and exert its will in shaping its communities and directing its nation (which sometimes seems, paradoxically, more oligarchy than democracy).”

The research plan included a series of deliberative forums held throughout the country on urgent national issues followed by reporting outcomes to policymakers…

…

In 1990, it was suggested, Kettering could build NIF’s influence in Washington, and its underlying vision of politics, through a widely distributed, annual report of the forums not much different from the National Town Meetings.

To envision the celebration’s annual national town meeting as a program televised from coast to coast was an incremental step forward. Kettering’s goal was to reach political and media leadership with a message about deliberative democracy and the public voice. To attract congressional attention, the reasoning went, NIF had to be of interest to a significant public audience in congressional districts.

The best way to ensure congressional attention to a public voice, it was felt, was to have congressional participation in the video. The second best way, it was further felt, was to ensure that the discussion was widely seen by elected officials’ constituents.

After reviewing several options, public television—considered to command a reasonable, national audience—was targeted. The foundation’s senior associate Bob Kingston was executive producer; Milton Hoffman, experienced in public affairs, public television programs, was the producer; and senior associate Diane Eisenberg handled distribution.

A Public Voice ’91, a one-hour public affairs television program was taped on April 15, 1991, at the National Press Club. It was the first time A Public Voice was used formally to describe forum outcomes. Bob Kingston was the moderator. Four members of Congress, four members of the press, and four members of the public joined him.

By September 5, 1991, 123 public television stations and 49 cable systems had broadcast the program and it was being distributed by community colleges to their local public access channels. The program continued to be produced in much the same format as the first one from 1991 through 2007. At its peak, A Public Voice was broadcast by nearly 300 public television stations across the country every year.

The program was seen as the central thrust in the foundation’s campaign to bring a new sense of politics to the consideration of the nation’s political and media leadership. The video had a single purpose: to show that there is something we can call “a public voice” on complex and troubling policy matters. And this public voice is significantly different from the debate on these issues as it is recorded in the media and significantly different from the debate “as we hear it through the mouths of political leaders.”

About Kettering Foundation and Connections

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

Each issue of this annual newsletter focuses on a particular area of Kettering’s research. The 2015 issue, edited by Kettering program officer Melinda Gilmore and director of communications David Holwerk, focuses on our yearlong review of Kettering’s research over time.

Follow on Twitter: @KetteringFdn

Resource Link: www.kettering.org/sites/default/files/periodical-article/Daley_2015.pdf

How Do We Show Dialogue’s Risks are Worth its Rewards?

Last month, NCDD Board member John Backman sparked lots of thoughtful conversation on our NCDD Discussion Listserv with the article below, and we wanted to share it on the blog too. His piece examines the fear we feel sometimes have around engaging in dialogue that could shift our stance on strongly-felt issues. He points out that for many average people, the idea of dialogue with “the other side” presents a risk – maybe real, maybe imagined – that allowing our opinions to shift might hurt some of our important relationships.

John’s article prompts us dialogue workers to take seriously what it sometimes means for us to ask people to take a risk like that, and it asks us how we can demonstrate that the risk is worth the reward. We encourage you to read John’s article below (original here) and let us know what you think about his questions in the comments section.

Guns, Changes of Mind, and the Cost of Dialogue

My opinion on government gun policy is starting to shift. That shift fills me with dread – and the reason, I think, may say a lot about why dialogue is such a hard sell.

Let’s start with my own biases. Temperamentally, I am as close to pacifist as you can get without actually being pacifist. Guns hold no appeal for me whatever (beyond the curiosity I have about pretty much everything). I grew up on Bambi. For most of my life, then, my thoughts on gun control were pretty much a default on the pro side.

But recent events have nudged me into more reflection. My experiments with gun dialogue (last month and in 2012) put me in contact with gun owners and their stories about why they value their guns, the enjoyment of pursuits associated with guns, the security they feel in owning a gun and knowing how to use it. Moreover, after pondering the Second Amendment, I can see how the standard gun owner’s interpretation may have some merit.

Bottom line: I can still support commonsense measures like background checks and waiting periods. But now, whenever cries to reduce gun ownership permeate the public square, I can’t quite join in – as much as my Bambi instinct still wants me to.

But this post is not about guns. It’s about why the shift scares me.

There are several reasons, but one towers above them all: some of the most important people in my social network – dear friends, immediate relatives, colleagues who might influence the course of my career – are vociferously anti-gun. I can think of a family member whose wisdom and love I would not do without… a colleague whose family has suffered several murders due to gun violence… a Catholic writer who shares many of my sensibilities but whose wrath grows with each mass shooting.

Will they abandon me now that I’m expressing a different opinion, even if just slightly different?

You might argue that it’s unlikely, and you’d probably be right. But in our current culture, friends and colleagues do part ways over disagreements like this. Consider the “harmonious” traditional family that fractures when a daughter comes out as gay, or good neighbors who find themselves on opposing sides when a casino comes to town. The notion that “if they abandon you over this, they weren’t real friends (or colleagues, or loved ones) anyway” is far too simplistic.

Now consider that I feel this dread strongly enough to hold my tongue around certain people – and I’m a dialogue person. How can I expect folks who are unfamiliar with dialogue to enter in when the risk is so high: when they might lose not only their basic convictions, but even their friends? How can those of us who care deeply about dialogue demonstrate that, in fact, the reward is worth the risk?

You can find the original version of this piece by John Backman on his blog at www.dialogueventure.com/2016/01/12/guns-changes-of-mind-and-the-cost-of-dialogue.

One Week in Manila: Democracy, Development, and “Transforming Governance”

Motiemarkt “Motion-Market”

Method: Motiemarkt "Motion-Market"

Video: US Judge Carlton Reeves on “Race and Moral Leadership”

Now that I’m finally catching up with my grant reporting obligations, I’m returning to work from October of 2015. We snagged some nice pictures of Judge Reeves while he was here and we recorded the video of the open forum discussion we held. U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves of Mississippi’s southern district caught my attention in particular with the speech he delivered at the sentencing case of a racially motivated murder in Jackson, MS. NPR called his speech “breathtaking,” and it certainly is.

When I read it I was so moved that after a period of absorbing his deeply thoughtful remarks, I felt compelled to write to him and tell him how much what he said meant to me and to Mississippi. On a whim, I ventured to invite him, were he willing and ever able, to come talk with one of my classes, particularly on the Philosophy of Leadership. He got back to me the same day to say that he would be delighted to come. That’s the kind of guy this now famous judge is. [Video is at the bottom of this post]

Here’s the bio on Judge Reeves that NPR put together after his speech had garnered over a million downloads. It was a profound honor to have Judge Reeves meet with my students and me for lunch, my class soon after, and then the campus and Oxford community members who came to hear and speak with him. Judge Reeves is also famous and to some controversial for his judgments on prayer in school and on same-sex marriage. Progressive Mississippians came to meet the judge to thank him for his leadership and several called him a hero to them. Judge Reeves explained at our lunch and to my class that when he was growing up, his moral heroes in Mississippi were federal judges.

Photo by Thomas Graning/Ole Miss Communications

The interesting thing about Judge Reeves’s position is that people think that judges must not be activists. Does that mean that they should not really speak up much on public issues? Judge Reeves thinks that they should. A judge should not be prejudiced in making his or her judgment on a particular case, but may, and Reeves argues should, voice their concerns about larger social issues and movements. I asked Judge Reeves whether he had been criticized for delivering the speech that he did at the sentencing for the murder of James Craig Anderson. Judge Reeves said just the opposite happened. If anything, people had issued threats because he upheld the Constitutional prohibition on governmental establishment of religion in public schools. For speaking up as he had, he explained, he had only received very positive feedback.

Photo by Thomas Graning/Ole Miss Communications

A judge holds a complex and interesting kind of leadership position, which is why I was eager to hear Judge Reeves talk about “Race and Moral Leadership in the U.S. Judicial System.” I certainly gained a great deal from his visit, and I welcome you to watch this video of the forum we held with Judge Reeves. Here it is:

Follow me on Twitter @EricTWeber and “like” my Facebook author page to connect with me there.