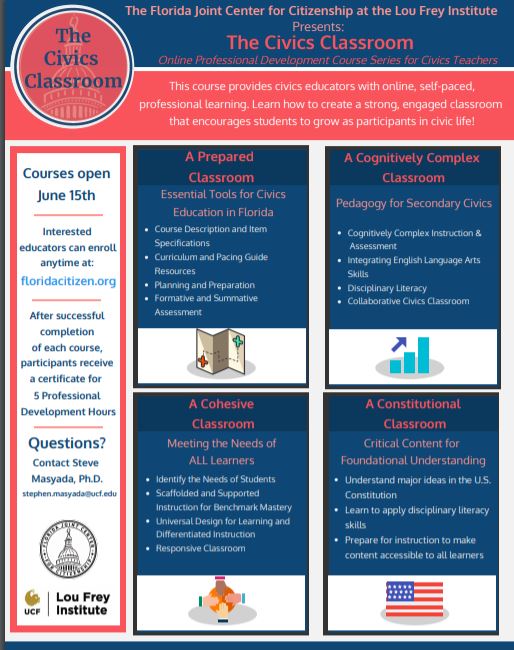

Good evening, friends! Are you looking for free online professional development? You may be interested, then, in our The Civics Classroom series.

A Prepared Classroom provides teachers with an understanding of:

- Course descriptions and the Civics End-of-Course Test Item Specifications,

- How to utilize curriculum and pacing guides,

- The value of strategic planning and preparing for instruction, and

- Making informed decisions about instruction based on formative and summative data.

A Cognitively Complex Classroom provides teachers with an understanding of:

- The role of cognitive complexity when facilitating instruction and assessment,

- Utilizing strategies and structures, and

- Developing learning activities that integrate English Language Arts and disciplinary literacy skills.

A Cohesive Classroom provides teachers with an understanding of:

- identifying the needs of students for scaffolded and differentiated supports aligned with the Universal Design for Learning and,

- how to develop a responsive civics classroom that builds academic and social-emotional competencies.

The fourth course in the series, developed in collaboration with our partners at Bay District Schools, explores the underlying ideas of the US Constitution and is ‘hosted’ by Dr. Charles Flanagan of the National Archives’ Center for Legislative Archives!

A Constitutional Classroom will provide teachers with an understanding of:

- Major ideas in the U.S. Constitution,

- How to apply disciplinary literacy skills, and

- Preparing for instruction to make content accessible for all learners.

You can get info to register for these courses and download the syllabi, over at Florida Citizen!

We have also completed and are now launching the first course in what we hope will be a strong and long series for high school US history! The High School US History: The Civil War and Reconstruction Era is, like A Constitutional Classroom, hosted by our friend Dr. Charles Flanagan from the National Archives’ Center for Legislative Archives and was developed in collaboration with our partners at Bay District Schools.

The High School US History: Civil War and Reconstruction course will provide teachers with pedagogy, content, and resources for:

- the major ideas of the cause, course, and consequences of the Civil War and Reconstruction Era

- primary sources and disciplinary literacy

- strategies and structures for accessible learning

But what about you folks in high school US Government? We have a new course for you as well!

The High School Government Classroom: Building Critical Knowledge course will provide teachers with pedagogy, content, and resources for:

- lesson planning and preparation in social studies

- the principles of American democracy

- the US Constitution

- Founding Documents

- Landmark Cases

For Florida teachers, this course is intended to help you prepare students for the new Civic Literacy Assessment. However, it also provides a basic foundation in US government content, pedagogy, and resources and aligns with the newHigh School US Government modules on Civics360!

We hope that you find these new courses beneficial!

Amani came to study in the United States from a middle-eastern country. She was on a government scholarship and had to meet specific academic benchmarks to keep it. Her freshman year consisted primarily of general education courses plus freshman English. Amani did well in her courses except for the parts that were discussion-based.

Amani came to study in the United States from a middle-eastern country. She was on a government scholarship and had to meet specific academic benchmarks to keep it. Her freshman year consisted primarily of general education courses plus freshman English. Amani did well in her courses except for the parts that were discussion-based.