This is the audio of my friend Andrew Seligsohn, the President of Campus Compact, interviewing me earlier this week about the election, what it tells us about civic life, and what we should do next. I enjoyed it and appreciated the opportunity. Follow Campus Compact for other #CompactNation podcasts.

modus vivendi theory

I am preparing for a weekend conference on modus vivendi–on how people can coexist peacefully even if they do not like each other one bit. The conference was planned a long time ago and has a global scope. Nevertheless, it feels timely to an American after the 2020 election.

Some of the papers are works of abstract political theory, with references to Hobbes and modern liberal or communitarian philosophers. Some are empirical, discussing the possibilities of trust and agreement when people differ. Some of them are about consociational and polycentric governance arrangements–when there isn’t one centralized state or one big market but several heterogeneous entities govern simultaneously. And some of the readings are about concrete situations. For instance, I highly recommend Informal Order and State in Afghanistan, by Jennifer Brick Murtazashvili.

I think one of the unresolved issues is whether to reduce interaction in order to preserve peace and liberty or to encourage interaction by decentralizing power so that people who dislike each other can still negotiate intensively without feeling that one group might use the state to dominate the others.

Murtazashvili depicts local governance in Afghanistan as a complex network of local leaders who have overlapping and limited powers and who collaborate quite often and compete for public support. This implies a lot of negotiation and communication. The overall system is adaptive, not rigidly traditionalist. One of the advantages of polycentrism, Paul Dragos Aligica emphasizes, is its openness to local experiments that others can observe and imitate (pp. 66-69). In short, polycentrism is helpful for learning, and we might expect people in a polycentric order to converge about what they learn over time. They would become more similar.

A different model is a classic consosiational arrangement, such Belgium, which allows different religious and linguistic communities to manage their own affairs independently and without much interaction. Shadi Hamid is convinced that religions are divided by fundamental normative assumptions, and when such divisions arise, it can be wisest to reduce interaction–to send the parties into their respective corners. “Sometimes, reducing contact between opposing sides and allowing for autonomous communities are ways of accepting that some differences cannot be bridged” (p. 36).

In the US context, it seems plausible that reducing the imprint of the national government might lower the temperature of partisan division. The problem with that solution is that some of us have strong commitments to federal intervention, whether on climate change, racial equity, or responses to COVID-19. Telling everyone to disengage at the national level so that the states and localities can do their own thing is biased toward some of the states and localities–the ones that vote for less rather than more social welfare. And it leaves minorities in each state exposed. I don’t think you can predict that progressives will stop demanding national policies, and I am not sure that we should stop.

But we could think about ways to address genuine common problems with a minimal footprint on the values that divide us most deeply. And you can think about that even when the values (e.g., racial or gender equity) are very worthy. I have long favored emphasizing cash transfers over behavioral interventions for this reason. I think that trying to change people’s behavior threatens liberty. It also provokes distrust that undermines the capacity of the national government. This is true even when the goal of an intervention is most worthy, such as educating against racism.

A strategy of lowering partisan polarization by reducing the explicit footprint of the national government may or may not work. And it doesn’t necessarily tell us clearly what we should actually do. For instance, you could argue that if the Supreme Court overturns Roe v Wade and allows states to ban abortion, the partisan temperature will fall as more people become satisfied by the policy in their own state. (This is the decentralized-democracy argument.) But you could also argue that if the government (at any level) is forbidden to ban abortion, the choice becomes personal, which is much more decentralized and prevents battles over state laws. (This is the liberal argument.) So far, we can see that Roe had worsened polarization, but we don’t know whether repealing it would reduce polarization or take it up another notch.

Another example: Tufts is going through an intense conversation about anti-Black racism. Very few people in our campus community evidently supported Donald Trump. Trump voters appear as an out-group, characterized either as complicit with racism or as people to be understood better–but not as part of the community. If people who voted for Trump were better represented at Tufts, the temperature might rise through the roof. I do not believe that the already complex conversations would survive that extra dimension of plurality.

Modus vivendi theory might say: It’s good that we have a heterogeneous, voluntary system of higher education. Let Tufts people go to their corner and have their own hard, important conversations, while Trump voters assemble in other places if they want to. Or modus vivendi theory might say: We need pluralism within institutions devoted to learning. Places like Tufts are relatively homogeneous ideologically. That is bad, and the solution is for the institution to say less in its own name so that a wider variety of views feel fully welcome. (Or maybe there are other ways of addressing this issue that don’t require modus vivendi at all.)

The idea of modus vivendi theory can be opposed to democratic, liberal, social-welfarist, and deliberative theories, but it’s also possible that negotiating a modus vivendi is the best way to advance those values when antipathies run high. In any case, I think there is much to be learned from this body of thought.

Cited sources: Paul Dragos Aligica,

EP Offers Four Weeks of Post Election Healing Support

With the elections behind us, Essential Partners, an NCDD sponsor member is offering post-election support. This assistance arrives straight to your inbox in the form of one newsletter per week over the course of the next 4 weeks. Each newsletter comes with guiding prompts and resources from the pool of experts and 30 years of experience of EP to better assists in continuing the work of healing and caretaking in all of our community circles. Click here to sign up to the EP email newsletter list! Read below to find the upcoming themes and for the original post here.

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? EP OFFERING 4 WEEKS OF POST-ELECTION SUPPORT

![]() The election is finally here. Years of campaigning, media coverage, social media shares, and protests have culminated in this one event.

The election is finally here. Years of campaigning, media coverage, social media shares, and protests have culminated in this one event.

Now we all turn to the pressing question: what happens next?

During this time of extreme polarization, fear of an uncertain future, and a general reticence to speak with people about what matters most, many dialogue organizations are bringing folks together for post-election conversations.

But we think there is a lot of work to be done—on a personal level, in our trusted circles, and in our larger networks—before our communities are healthy enough to come together again for that kind of dialogue.

Essential Partners will spend the next four weeks doing what we do best—empowering you to repair the fabric of your community, piece by piece. In one email each week over the next four weeks, we will draw on 30 years of experience to offer guidance and resources in support of this crucial work. Click here to sign up to the EP email newsletter list. Here’s what we have planned.

Week 1: Your Best Political Self

We’ll begin with ourselves, taking some much-needed time and space to reflect on what matters most to us and who we want to be.

In this first week, we’ll share a tool to help you think about the stories that inform your political values, the people who influenced you, and the places where you grew into yourself.

We want to help you become curious about who your best political self is—and how that connects to what you decide to do now that the election season is over.

Click here to download the free Week 1 resource.

Week 2: A First-Draft Conversation

Next, we’ll give you a resource to have an intentional conversation with someone who knows you best, someone you trust and feel fully yourself with.

It has been hard to escape the polarizing forces of this election cycle and easy to lose yourself in the campaign. Our resource will help you reflect deeply, with someone close to you, on how you’re doing as this election season comes to a close and on what matters most as you think about the challenges you’ll face next.

This is a first draft conversation. It might be messy. Our hope is that you will be able to worry less about speaking carefully in this first conversation because you’re already so well understood by the other person.

We want to invite you to practice talking about your values and priorities in ways that feel connecting, valuable, and important.

To be published: Tuesday, November 17

Week 3: Building Community

With three weeks of reflection, and some space from the election, try connecting with someone in your life who might feel isolated because of the outcome. This could be a family member, colleague, fellow parishioner, or an acquaintance.

That person doesn’t have to believe something different than you (although they might). They might feel like they’re the only person with their beliefs in the room, the only one who hasn’t responded in the way others have, that they aren’t welcome in conversations, or have felt excluded in the past.

You’ll be given guidance on how to help that person feel heard, fully and seriously. It’s a chance to build or re-build relationships on a foundation of trust and understanding.

To be published: Tuesday, November 24

Week 4: A Group Conversation

Finally, we want you to think of this series as culminating in group conversations. In the last week, we’ll provide tools for you to lead a group discussion that welcomes different perspectives and begins to repair your community after the divisive 2020 election.

This doesn’t have to be a formal dialogue. Maybe it’s a family conversation over a holiday dinner, part of a check-in during your weekly team meeting, or part of a classroom discussion.

To be published: Tuesday, December 1

Whatever the circumstances are, know that better conversations don’t happen overnight. It takes work and time for people to bring their best selves to a discussion across different perspectives—especially in the wake of a polarized conflict like this. But these are necessary conversations if we want to move forward together.

Click here to sign up to the EP email list if you want to receive post-election resources.

If you feel like you need help urgently, you can also reach out to us for a free consultation. We are here to help all those who do the hard work of tending to the health of their community.

You can find the original version on this on the Essential Partners’ site at https://whatisessential.org/what-happens-next-ep-offering-4-weeks-post-election-support.

upcoming public events

Now that all of life occurs on Zoom, it’s easy to join events like these:

Tufts 2020 COVID-19 Research Symposium: Research. Policy. Solutions. Nov 17-18, 9:00-2:00. #TuftsCOVIDResearch

The Tufts 2020 COVID-19 Research Symposium will be two half-days of panels and talks on many aspects of the pandemic: biomedical, public health, economic, political, and more. I have served on the planning committee and will moderate the panel on “Equity in the COVID-19 Pandemic” (Nov 18, 1:00pm – 1:45pm). People who read this blog may also be interested in the panel on “Cultural and Political Impacts of Disinformation in the Pandemic,” Nov. 18, 10:00am – 10:40am. The keynote speakers for the event as a whole are Dr. Soumya Swaminathan, Chief Scientist, World Health Organization and Dr. Eric Rubin, Editor-in-Chief, New England Journal of Medicine. All of the presentations will be open to the public. Register here.

The Upswing: How America Came?Together a Century Ago and How We?Can Do It Again, November 18, 5:30 PM

Join Tisch College for a conversation with author, professor, and thought-leader Robert Putnam, and co-author and social entrepreneur Shaylyn Romney Garrett to talk about their latest book, The Upswing: How America Came?Together a Century Ago and How We?Can Do It Again. The Upswing is an analysis of economic, social, and political trends over the 20th century, demonstrating how we have gone from an individualistic society to a more communitarian society—and then back again. How we can learn from that experience to become a stronger, more unified nation?

I will interview Putnam and Garrett and moderate the discussion. Register here.

Mass. Humanities “Let’s Talk about our Democracy” series, “Threats to our Democracy in Historical Context,” Thurs., Nov. 19: 7:00-8:00 pm

Peter Levine, an expert on civic engagement, will moderate a conversation and audience Q & A with Suzanne Mettler and Robert Lieberman, authors of the new book Four Threats: The Recurring Crises of American Democracy. By studying previous periods in history when our democracy has been in peril, they discovered four recurring threats: political polarization, racism and nativism, economic inequality, and excessive executive power. Today, for the first time in American history, all four threats are present at the same time, a convergence that marks a grave moment in our democratic experiment. Yet history also points the way to imagine a path toward repairing our civic fabric and renewing democracy. Register here.

Mass. Humanities “Let’s Talk about our Democracy” series: The Promise of Civic Renewal to Revive our Democracy, Dec. 10, 2020: 7:30-8:30

Peter Levine, an expert on civic engagement, will talk with Program Officer Jennifer Hall-Witt about a promising vision for reviving our democracy, focusing on the role that ordinary citizens can play in fostering more deliberative, collaborative, and engaged communities. This conversation will be based on the findings in his book, We are the ones we have been waiting for: the promise of civic renewal in America, which advocates for a new, citizen-centered politics capable of tackling problems that cannot be fixed in any other way.

This event will include small-group discussion in breakout rooms amongst members of the audience. Please come ready to listen and participate. Register here.

Reporting on All Narratives/ Hidden Common Ground in Unprecedented Times

The growing sense of division in our country has been felt strongly this year in conjunction with the physical separation of pandemic life and elections right around the corner. This article published on USA Today, written by David Mathews, President of Kettering Foundation, explores a narrative that is rarely reported on. USA Today networks and America Amplified, a public media collaborative, equipped with research provided by organizations including Public Agenda and the Kettering Foundation want to uncover the common ground. The main findings reported demonstrate more common ground exists than we realize, and sustains the possibility of collaboration as divergent narrative for Americans and journalists alike.

To read the op ed in detail read below and for the original posting on USA Today click here.

How Americans can learn once again to solve our nation’s problems together

To solve really difficult problems, people realize that they have to work with others who may be different.

The year 2020 will go down in history as extraordinary. Americans, by most accounts, are deeply divided. They can’t even talk to those they disagree with.

Many people appear traumatized by fear. Some insist that change is long overdue. Some see the country sliding into moral chaos and want to preserve what they value in the American way of life. But there is little agreement on what needs to change or what needs to be preserved.

That’s the dominant story. But it isn’t the only one.

In covering the 2020 election, some journalists are telling another story. The group includes the USA Today Network and America Amplified, a public media collaborative. They are drawing on nonpartisan research provided by organizations including Public Agenda and the Kettering Foundation, where I work.

Kettering’s research draws on nearly 40 years of results from local deliberative forums held by a nationwide network known as the National Issues Forums. Here are the main findings from our research:

►There is more common ground on policy issues than is recognized. People favor such policies as increasing economic opportunities, providing for affordable childcare and keeping jobs in the U.S. But the thing Americans agree on most is that there is too much divisiveness — even if they contribute to it sometimes.

►Citizens and government officials often talk past one another, which makes the loss of public confidence in government grow even greater. For instance, on health policy, those in government are naturally concerned about the cost to their budgets. But NIF forums show that people are most concerned about a health care system so complex it is almost impossible to navigate.

►Despite the tendency to favor the likeminded, in some circumstances people will consider opinions they don’t like. There is a space between agreement and disagreement, an arena in which people decide, “I don’t particularly like what we are considering doing about this problem, but I can live it — for now.”

This is the arena of pragmatic problem-solving. Observers of National Issues Forums have seen people move into it even on explosive issues like immigration. Described as a pivot, it changes the tone of decision making. When it happens, problem solving can move forward, even without total agreement.

This pivot occurs when issues are described in terms of what people find deeply valuable — not “values” but age-old imperatives like safety and being treated fairly. When issues are described in this way and framed with several options for solutions, with both advantages and disadvantages clearly laid out, people will confront tensions between what they prefer and consequences they may not like.

Recognizing that everyone is motivated by the same basic imperatives removes barriers to listening to others who may not be like us or even like us. Even if people disagree, they become aware of greater complexity. They explore the tradeoffs inherent in difficult decisions. That opens the door to understanding the experiences and concerns of others.

the highest turnout ever

“Turnout” is usually defined as the percentage of legally eligible people who actually vote. So defined, turnout was higher back in 1900, when no women and few African Americans were permitted to vote. But if we want to measure how democratic the society is, it’s better to ask how many people voted out of the whole population. By that measure, 2020 will be the best year in US history.

This graph assumes that 149.5 million Americans voted in 2020, although that number may actually be higher. It implies that 45 percent of the people voted. That beats the previous high of 43.9 percent in 2008. Note that the ideal rate would not be 100%, because the population includes people of all ages, even babies. But 45 percent is not high enough.

Population estimates from the decennial Census, with my own linear estimates for the intervening years. Number of votes cast from Dave Leip.

National Civic Review Fall Edition Recently Released with Kettering Foundation

NCDD member org, The National Civic League released the 2020 Fall Edition of the National Civic Review, published in collaboration with NCDD member, the Kettering Foundation. This esteemed quarterly journal offers insights and examples of civic engagement and deliberative governance from around the country. Friendly reminder that NCDD members receive the digital copy of the National Civic Review for free! (Find the access code below.) We strongly encourage our members to check out this great resource and there is an open invite for NCDD members to contribute to the NCR. You can read about NCR in the post below and find it on NCL’s site here.

National Civic Review Fall Edition 2020 – Access Code: NCDD20

As this edition of the National Civic Review goes out, our nation is approaching a crucial presidential election, dealing with a terrible pandemic and grappling with vexing racial disparities. An article by Martín Carcasson discusses approaching the challenge of public deliberation as a “wicked problem,” in other words, an issue or challenge with conflicting underlying values and no technical solution. Perhaps at this juncture we are in a wicked time, a period with similar attributes of conflicting values and complexity. This edition of the Review was published in collaboration with Charles F. Kettering Foundation. We hope the articles in the edition will provide some ideas and tools to rally communities across the country to address complex issues and thrive.

You can access this edition by going directly to the table of contents and entering your access code (NCDD20) when prompted.

One of the Nation’s Oldest and Most Respected Journals of Civic Affairs

Its cases studies, reports, interviews and essays help communities learn about the latest developments in collaborative problem-solving, civic engagement, local government innovation and democratic governance. Some of the country’s leading doers and thinkers have contributed articles to this invaluable resource for elected officials, public managers, nonprofit leaders, grassroots activists, and public administration scholars seeking to make America’s communities more inclusive, participatory, innovative and successful.

how did we respond? what next?

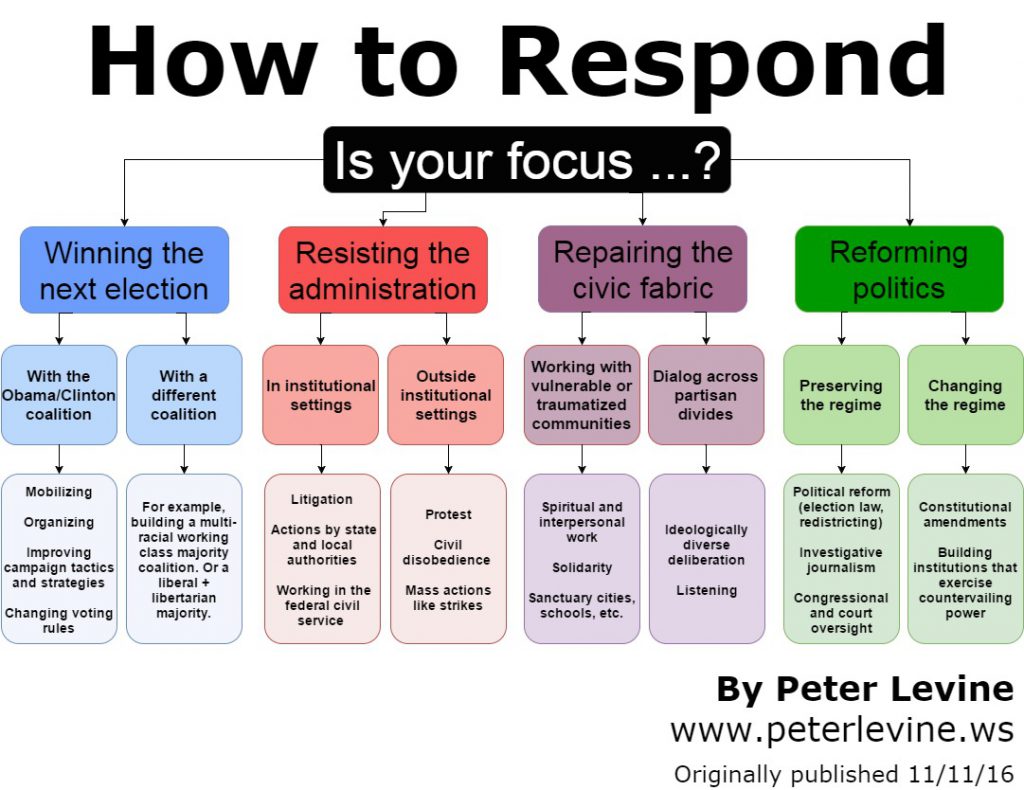

A few days after the 2016 election, I posted a flowchart with options for responses. It was by far my most-shared post in decades of blogging and was used a fair amount in grassroots meetings between 2016 and 2018.

This is a better version of the same graphic:

Two questions: How much was done in each of these boxes in 2016-18? And what is most important now?

The anti-Trump side did win the next two elections, although by a closer margin in ’20 than some might have expected. I think we observed a complex mix of all the ideas in that column, from changing some voting rules to building new coalitions. However, at the national level, the majority coalition is mainly the same as the one that elected Obama, and not larger as a percentage of the population.

Characterizing Black Lives Matter and climate mobilization as “resistance to Trump” is reductive: those movements were already underway before his election and will continue after, frequently targeting Democrats. Still, the combination of protest and litigation has been pretty effective.

Under “repairing the fabric” are two importantly different paths. Many people have worked hard on both. For examples of work in the cross-partisan lane, see Braver Angels, the Bridge Alliance, the Civic Health Project, and many other groups. Meanwhile, institutions and communities are paying attention to vulnerable people.

Both strategies are very hard, and the main trends are against them. Trauma and affective partisanship have intensified, which doesn’t take anything away from the people who are combatting either or both. The situation might well be even worse without these people, but now is a time to reflect on larger-scale strategies.

The last column is about preserving or changing the “regime.” I didn’t mean that word as pejorative; it’s just political-science talk for the government plus the other institutions that connect to it, such as parties and the media. The current regime survived but is surely fragile–see a recent piece of mine for some reasons.

Which of these paths should we emphasize next? My predictable answer is: all of them. I thought that a Biden administration would face a genuine dilemma: either fighting for valuable political reforms that would be seen as partisan or else reducing partisanship. GOP control of the Senate may simply preclude political reform at the national level, which might be an argument for focusing a four-year Biden administration on lowering the partisan temperature. That doesn’t mean that political reform is dead, because it has potential at the state and city level.

I remain interested in policy approaches that could possibly expand the majority while disrupting partisanship by assembling strange bedfellows. For instance, libertarians should be (and often are) appalled by Trump and can find substantive common ground with left-liberals on some policies, e.g., criminal justice reform.

A related strategy is to emphasize certain bread-and-butter policies that involve the government less in people’s lives while still boosting economic equity. A minimum wage referendum passed in Florida even as Trump won the state. The reason could be that there’s a latent majority for left-economic policies that the Democrats missed by nominating a moderate. (That’s the “Bernie would have won” argument.) A different explanation is that people don’t like the government or taxes, partly because they see the government as the representative of hostile cultural values, but they’re happy to pass unfunded mandates on the private sector. This kind of social policy has promise if the outcomes are actually beneficial.

See also white working class alienation from government; promoting democracy and reducing polarization; some remarks on Elinor Ostrom and police reform; political reform in Massachusetts, etc.

post-election resolution #3: don’t argue on the basis of election counterfactuals

On Tuesday night, when things looked dimmest for Biden-Harris, I saw plenty of “Bernie would have won” tweets, and also some arguments that the Democrats would gave done better if they had been more moderate on immigration. On the GOP side, too, there will be arguments about whether the party would have performed better if all their candidates were more Trumpian or whether Trump cost them the White House despite strong economic fundamentals.

It is important to argue about: (a) what is valuable and (b) what is politically feasible. The union of those two circles is what we ought to support. People disagree about both questions, and discussion can be helpful.

Our values can influence our estimates of what would win. If you are further left, you may be biased to believe that leftist policies would win–and the same for people all across the spectrum.

However, disciplined political thinkers try to separate the two matters in case what they want may mislead them about what they can win.

It almost never helps to argue with counterfactuals about past elections. The problem with “Bernie would have won” is not that it’s false. It’s unfalsifiable, untestable. It provides no analytic clarity.

I acknowledge that social science often seeks to estimate counterfactuals. For instance, a regression model estimates what would happen to the dependent variable if the independent variable changed from what it actually is. (If we spent more on preventive healthcare, the data may suggest, fewer people would get sick.) This kind of reasoning is essential for thoughtful planning. However, to make counterfactual inferences, we need the right conditions: usually lots of cases, each with many variables, from which we can infer trends. Natural experiments also work nicely. A given election is one ambiguous datapoint that can fit countless theories.

So my resolution is: I will argue about what I value and whether it can win the next election, but not what would have won in 2020. I think that’s a recipe for confusion. In any case, I am not looking forward to that particular form of debate.

post-election resolutions #1 and #2 (less forecasting and less hobbyism)

Today seems an auspicious occasion to begin posting resolutions for becoming a better person and citizen after the 2020 election.

The first and second resolutions are simple:

- Less forecasting, more living in the present. Surveys are valid research tools, but they are particularly hard-pressed to predict future behavior with precision. The polling error that shows up in forecasting sites like FiveThirtyEight reflects the complexity of screening for likely voters–it doesn’t invalidate survey research. But why are we checking FiveThirtyEight in the first place? All the sages teach that we should live in the present or work to change the future. Forecasting violates that advice, but it is almost literally addictive: you get a little dose of pleasure every time a prediction is favorable, and when it isn’t, you can go back for another fix. I hope I can use the methodological limitations of electoral forecasting as a reason to pry myself away from the habit of forecasting everything (COVID-19, the stock market, my own life expectancy).

- Less “political hobbyism.” People gave $100 million to Amy McGrath. In many cases, they were doing something to harm Mitch McConnell after he did or said something that made them mad. It didn’t work; he won by 20 points. One hundred million dollars is a lot of money. You could start a new college for that. Part of the problem is a profession–political consultancy–whose interests align poorly with the public interest. Someone made a fortune by fundraising for McGrath. (I wrote an article about this in 1994.) Expressing anger by giving money also has an allure; it’s an easy thing to do after observing something that makes you angry. I actually didn’t donate to Amy McGrath (ironically, I was too aware of the skeptical forecasts for her), but I exhibited other symptoms of political hobbyism in this cycle.