While NCDD member org, Everyday Democracy, shared this article on the importance of civics education a while back, we wanted to lift it up because it is still so relevant. The article talks about how education in this country has shifted from preparing students to be more civically engaged, to training students for the workforce. While the latter is important, our democracy suffers when the people are not trained on how to be civic agents. The article stresses that in order for our democracy to thrive and for our communities to be stronger, people needed to have civics a part of modern education. You can read the article below or find the original on Everyday Democracy’s site here.

The Decline of Civic Education and the Effect on our Democracy

When I was five years old, my parents dropped me off at Radnor Elementary School for my first day of Kindergarten. This was the first day of many years of public education for me.

When I was five years old, my parents dropped me off at Radnor Elementary School for my first day of Kindergarten. This was the first day of many years of public education for me.

My high school, like so many in our country, steers students towards science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. Personally, I was lucky enough to have great teachers who encouraged me to look beyond this narrow focus and find subjects that interested me, but my story is the exception rather than the rule.

In the past few decades, the focus of our public education system has turned sharply toward STEM as part of a broader reconceptualization of the role of public education. Whereas education was once seen as a public good designed to prepare students to participate in our democratic system, it is now seen as a primarily individual pursuit intended to help people develop employable skills and prepare to contribute to the workforce.

A little bit of history on the public education system

To better understand this monumental shift, it is important to understand where our public education system comes from. The history of public education in the U.S. is inseparable from the history of our nation, and I believe that their futures are intertwined as well.

Before the American Revolution, school was primarily for the lower and middle classes. Wealthy families hired tutors for their children, so only parents who could not afford tutors sent their children to school. A few colonies had experimented with state-supported education in the 17th century, but these early public education systems had mostly died out by the middle of the 18th century.

Under British rule, colonists had no reason to care whether or not their neighbors were sufficiently educated. There were plenty of ways for people with very little education to support their families and average colonists had very little political power.

The Revolution changed that: we fought a war for the idea of republican government, and now we needed citizens who could sustain it. In a letter discussing the soon-to-be-held Constitutional Convention, John Adams wrote that “the Whole People must take upon themselves the education of the Whole People and must be willing to bear the expenses of it.” This belief was widely shared amongst the founding fathers, who recognized that a people transitioning from subjects to citizens would need to be educated in order to serve the many functions required of them in the new republic.

After the Revolution, American citizens would need to decide who would represent them, know when their representatives had violated their trust, serve on juries, and possibly decide on Constitutional Amendments. Education had to reflect this reality by teaching history, rhetoric, and government in addition to literacy and arithmetic.

While some states headed the call of the founding fathers and created state-supported public education systems, most states needed more persuading. This persuading came in the form of widespread demographic changes.

From 1820 to 1860, the percentage of Americans living in cities nearly tripled. Caring for the poor residents of these cities was expensive, and the fact that many of them were Irish and German immigrants bred resentment. To cities looking to reduce poverty, assimilate immigrants into American culture, and keep people out of trouble, institutionalized education systems made a lot of sense. In 1918, Mississippi became the last state to embrace compulsory education; and no state has abolished its public school system since.

Civic education

The rise of public education was motivated by the need to prepare students to participate in American life as citizens, workers, and community members. While the early public education system took all three dimensions of their mandate very seriously, the rhetoric surrounding public education today has a very different focus.

You have probably heard some variation of the argument that American students are falling behind the rest of the world and we need to invest in science and math education so that our economy can stay competitive. You may have seen college majors ranked by post-graduation earning potential, or read about how educational attainment is a “signaling device” to employers, or heard some of the arguments for and against the “Common Core Standards.” These opinions are well-intentioned, but they all focus on a single educational outcome: career success.

To be clear, I believe that education ought to prepare students to participate in the workforce. I recognize that the increased economic opportunity that comes with educational attainment is a primary motivator for many students to attend school, and I am not suggesting that career success is not an important focus of our public education system. Instead, my argument is that our obsession with the economics of education comes at a substantial cost in terms of civic health, which in turn introduces new risks to our economic stability.

According to a 2015 study conducted by the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania, only 31% of Americans can name the three branches of government (and 32% cannot name a single branch). In 2011, when Newsweek administered the United States Citizenship Test to over 1000 American citizens, 38% of Americans failed. This widespread civic illiteracy is not just shameful, it is dangerous.

How can we expect people to hold their representatives accountable when 61% don’t know which party controls the House and 77% can’t name either of their state’s senators? How can we expect Americans to exercise their rights when over one third can’t name any of the five rights protected by the First Amendment (freedom of speech, religion, the press, protest, and petition)?

Our democratic system depends on citizens to take an active interest in the affairs of our government, develop informed opinions about how our government should act, and chose representatives who share their beliefs about the direction our country should take. When legislators know that their constituents do not know or care what they are doing, it gives them an incentive to cater to the lobbyists and special interest groups who are scrutinizing the legislators’ actions. From 1964 to 2012, the percentage of Americans who believed that government is “pretty much run by a few big interests” increased from 29% to 79%, while the percentage of Americans who believed that it was run “for the benefit of the people” decreased from 64% to 19%.

Citizens of a Democracy do not have the luxury of refusing to care about their government. We the People are ultimately responsible for what our representatives do on our behalf using our collective power. Willful ignorance does not absolve us of this responsibility.

Civics education teaches students how to fulfill this essential responsibility, which is why the public pays for it. If education were all about training people for jobs, we would expect employers to pay for the basics and individual students to pay to train for more advanced jobs. Instead, we recognize that citizens need a certain amount of education to carry on our democratic traditions and that it is in the public’s interest to ensure the future stability of our country. Part of that stability is preparing people to get jobs and contribute back to society financially, but the main part is ensuring that people understand the role they play in our system and are able to play that role.

Strong civic health means stronger communities

There is also a growing body of research that suggests that communities with strong civic health have stronger economies, were more resilient during the financial crisis, and have higher rates of employment. When people come together with their neighbors to identify, discuss, and solve community problems, they build relationships and develop skills that ultimately help all of them economically as well as personally.

Nobody will make us be citizens. If we do not want to understand how government works or what it is doing, we can give our political power to someone else. There are plenty of countries who have vested that power in a monarch, party, oligarchy, aristocracy, technocracy, emperor, etc. Subjects in these countries have no need to trouble themselves with public affairs, and we could be like them; but, as Plato once wrote, “the heaviest penalty for declining to rule is to be ruled by someone inferior to yourself.”

In the United States, we the people have decided to take responsibility for governing, and we temporarily delegate some of that responsibility to our elected representatives and the unelected officers they select. We benefit tremendously from living in a democratic republic, but these benefits are not without cost.

For the last several decades, the focus of our education system as shifted from civics to job training, and we have all paid a steep cost. Special interest and lobbying groups have unprecedented power over our political system. A lack of knowledge about public affairs has made citizens more susceptible to political advertising, which has given the wealthy tremendous power to shape politics through campaign contributions and ad spending. So few Americans trust the political system that nearly half of 2016 primary votes went to candidates promising anti-establishment revolutions.

If we really care about preserving our democracy for future generations, we will stop treating civics education as secondary to math and science instruction and put it back at the core of our school curricula.

You can find the original version of this article on Everyday Democracy’s site at www.everyday-democracy.org/news/decline-civic-education-and-effect-our-democracy.

To kick off the first week of the Local Civic Challenge, we want you to learn more about the ins and outs of your city government! That includes how it operates, who’s involved, and ways you can give feedback. Once you’re done, you’ll be more familiar with how the system works, and you might even have some ideas on the ways things could be improved.

To kick off the first week of the Local Civic Challenge, we want you to learn more about the ins and outs of your city government! That includes how it operates, who’s involved, and ways you can give feedback. Once you’re done, you’ll be more familiar with how the system works, and you might even have some ideas on the ways things could be improved.

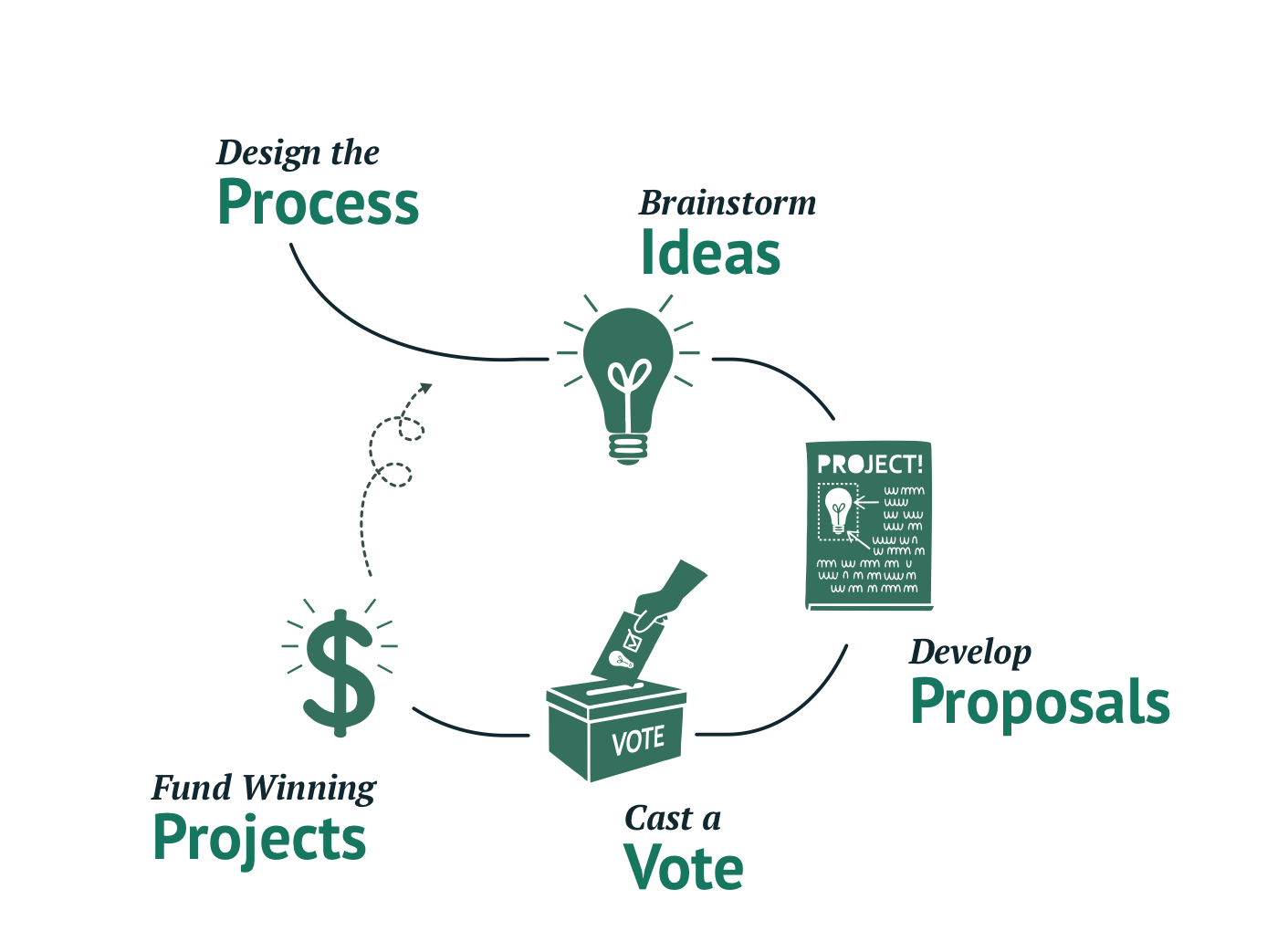

To create truly inclusive PB processes, low-income residents and people of color must be well represented on the steering committee and as budget delegates. The steering committee sets the rules for a PB process, and these rules ensure an inclusive and fair process. When low-income people and people of color are not in the room, steering committees miss valuable ideas on how to create a fair process.

To create truly inclusive PB processes, low-income residents and people of color must be well represented on the steering committee and as budget delegates. The steering committee sets the rules for a PB process, and these rules ensure an inclusive and fair process. When low-income people and people of color are not in the room, steering committees miss valuable ideas on how to create a fair process.

Government representatives should make themselves open and available to their community. Simple changes in tone and body language can mean the difference between intimidating residents and engaging them.

Government representatives should make themselves open and available to their community. Simple changes in tone and body language can mean the difference between intimidating residents and engaging them. Some residents told Celina that they would not have voted for surveillance cameras had they known that the community would not have had control over the footage. It’s critical that PB participants understand the ramifications of what they are voting for so that they can make an informed decision.

Some residents told Celina that they would not have voted for surveillance cameras had they known that the community would not have had control over the footage. It’s critical that PB participants understand the ramifications of what they are voting for so that they can make an informed decision.

This week, our new cohort of Nevins Fellows will start working with organizations around the country that advance democracy in a variety of areas.

This week, our new cohort of Nevins Fellows will start working with organizations around the country that advance democracy in a variety of areas. On the call, John Gable and Jaymee Copenhaver of Allsides started off the conversation by sharing how polarization has shifted here in the US and that our country has never been as polarized as it is now. They pointed out the dangerous combination of the 24 hr news cycle, massive polarization, and increasing tendency for people to live in bubbles has people more extreme in their beliefs and significantly less tolerant.

On the call, John Gable and Jaymee Copenhaver of Allsides started off the conversation by sharing how polarization has shifted here in the US and that our country has never been as polarized as it is now. They pointed out the dangerous combination of the 24 hr news cycle, massive polarization, and increasing tendency for people to live in bubbles has people more extreme in their beliefs and significantly less tolerant.