Monthly Archives: November 2016

recent commentary by our team

I am not sure I have anything new to offer to the cacophony of Election Day, but I’ll cite some recent summary articles by our team or by reporters who have delved deeply into our research:

Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, “Climate change could be a unifying cause of millennials, but will they vote?,” The Conversation, Nov. 7.

Peter Levine with Abby Kiesa, “Why American Urgently Needs to Improve K-12 Civic Education,” The Conversation, Oct 30, 2016

Noorya Hayat and Felicia Sullivan, “Civic Learning and Primary Sources,” The School Library Connection, Nov. 7.

Peter Levine, “Teach Civic Responsibility to High School Students,” The New York Times (“Room for Debate” feature), Oct. 17, 2016

In the Parent Toolkit, “One Week Away: Why You Should Talk to Your Kid About the Election”

Zachary Crockett, “The Case for Allowing 16-Year-Olds to Vote,” Vox, Nov. 7.

Asma Khalid, “Here’s Why Hillary Clinton’s Troubles Aren’t Millennials’ Fault,” NPR News, Nov. 4.

Catherine Rampell, “Parallel Universes, Even Among the Young,” The Washington Post, Oct. 28.

Get Ready for Messy Democracy: Public Officials on Participatory Budgeting

The Day After Tomorrow

People keep asking me how I feel about tomorrow’s election.

I’m not quite sure how to answer that question.

I feel relieved that the endless cycle of repeating political ads will be finally be broken. I feel excited at the prospect that a woman may be elected president for the first time; 240 years after this country’s founding.

But mostly, I feel an impending sense of doom.

Not so much about the election itself, but about the day after the election – about how we move on after this nasty, divisive campaign season in an increasingly polarized country.

I don’t mean to glorify the past, here – politics has always been messy, scandalous, and far less ideal than we might hope or pretend. But with my limited life time of experience, it seems like things have gotten particularly bad.

In All the Truth Is Out: The Week Politics Went Tabloid, political journalist Matt Bai tracks the fall of Gary Hart. The dashing young Democrat who in was on the road to becoming his party’s Presidential nominee until a sex scandal took him down in 1987.

Today, that story seems unremarkable – what politician hasn’t been taken down by a sex scandal? But Hart’s story is remarkable because it was the first. As Bai argues, the Gary Hart affair marked a turning point in American political journalism, a moment when public life ceased to allow a private life.

And perhaps this is being over dramatic, but it feels like we are hitting another tide right now. A point where we’re all accustomed to being entrenched in our own point of view, where the line between fact and opinion has become irreparably blurred.

In the field of Civic Studies we don’t just complain about the many failings of civic society, but rather we ask “what should we do?”

As I ponder the future on this election-eve, my best answer to that question is to first get out and vote, but to then get out and talk – to your friends, to neighbors, and to strangers. Or perhaps, I should say: next, get out and listen.

No matter who wins this election, the hardest work – the work of reuniting folks across this great land and the work of finding space in our hearts to respect everyone in it – that work will fall to us.

Tomorrow, we perform a small civic duty and vote. The day after that the real work begins.

Strategic Global Intervention

Method: Strategic Global Intervention

Participate in NCDD’s #BridgingOurDivides Campaign

As the election winds down, ballots are counted, and the debates about the many decisions on the ballot finally have clear outcomes, we have arrived at a time when we as a field need to take stock of what we should do next. A major theme of our NCDD 2016 conference in Boston was how D&D practitioners can help repair our country’s social and political fabric, both after this bruising and bitter election year, but also in light of many of the longer-standing divisions in our country.

As the election winds down, ballots are counted, and the debates about the many decisions on the ballot finally have clear outcomes, we have arrived at a time when we as a field need to take stock of what we should do next. A major theme of our NCDD 2016 conference in Boston was how D&D practitioners can help repair our country’s social and political fabric, both after this bruising and bitter election year, but also in light of many of the longer-standing divisions in our country.

NCDD has made an ongoing commitment to answering that question, and as part of that commitment, we are calling on our members and others to enlist in our new #BridgingOurDivides campaign!

In this new effort, NCDD is asking our members to help us collect information about the projects, initiatives, or efforts that you and others are undertaking to help our nation heal our divisions and move forward together, with a special focus on collecting the best shareable resources that folks are using to support or spark bridge building conversations in the aftermath of the election and beyond.

collecting the best shareable resources that folks are using to support or spark bridge building conversations in the aftermath of the election and beyond.

To do that, we ask that you share about those efforts and resources in the comments section of this post – post your links, write ups, reports, and descriptions that will help NCDD and others learn about divide bridging efforts you’re connected to, whether they are election-related or not.

In addition, we want to foster a broad conversation about what our field is doing and offering to bring people together to discuss difference and find common ground, so we are encouraging everyone to join the conversation on social media by sharing those comments, resources, links, and thoughts about this work using the hashtag #BridgingOurDivides. This will be a great way to increase the visibility of our field’s work, and we hope it also increases support for NCDD, so we encourage you to include a link to NCDD’s “Get Involved” page at www.ncdd.org/getinvolved, too! (You can also use the shorter bit.ly/ncddinvolve for tweets.)

There are already some great efforts to bring people together across divides in the NCDD network now:

- The Utah Citizen Summit is being convened by the Salt Lake Civil Network and the Bridge Alliance as part of the ongoing effort to help bridge partisan divides

Essential Partners is working to start forward-looking, post-election conversations on social media with their #AfterNov8 hashtag, which we encourage everyone to participate in alongside the #BridgingOurDivides conversation

Essential Partners is working to start forward-looking, post-election conversations on social media with their #AfterNov8 hashtag, which we encourage everyone to participate in alongside the #BridgingOurDivides conversation- The Americans Listen project is calling on everyday people to have empathetic, one to one listening conversations with Trump supporters about both what they find appealing about his message and what keeps non-supporters from really hearing their concerns

These are just a few examples of projects that are #BridgingOurDivides, and we know that the NCDD network is full of thoughtful, creative people engaged in many more. So tell us – what are you doing or planning to do that is bridging our divides? Not just the divides exposed or widened during the election, but the ones that were there before as well? Share all about it in the comments section below and on social media!

Our nation’s divides, whether related to the election or not, didn’t emerge over night, and they certainly won’t be bridged overnight either. But we at NCDD believe they can be healed – one conversation at a time. Join us in helping the world see how, and support us in this effort.

Joseph Schumpeter and the 2016 election

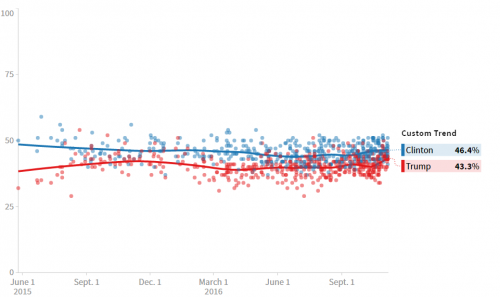

The graph below depicts the 2016 campaign as I see it. When all the polls are displayed on a graph with a y-axis from 0-100% and a fairly strong “smoothing” algorithm is applied, it becomes evident that hardly anything has changed for 18 months. Hillary Clinton has been ahead of Donald Trump by about 4-5 points nationally all along, and she leads by a mean of exactly four points in the major final polls released by this point on the last Monday. The ups and downs revealed by zooming in are best understood as temporary responses to news that may influence who participates in surveys–or who feels enthusiastic on a given day–but very few people have actually changed their minds; and most of those switches have been random and have canceled each other out.

I think this means that Clinton is likely to win the national popular vote by about 4 points, although GOTV operations could change result that (in either direction).

It’s hard to know whether different nominees would have performed differently. A reasonable guess is that if both parties had nominated politicians with typical levels of popularity who used typical methods of campaigning, the Republican would have an edge. That implies that Trump v. Clinton costs the GOP maybe 4-6 points, net–but that is not much more than a guess.

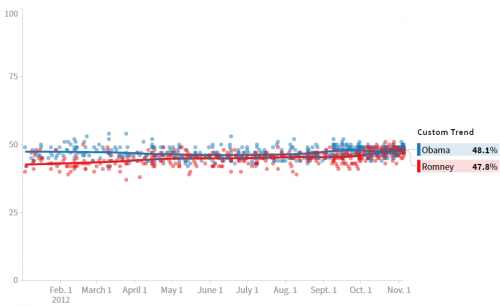

By the way, 2012 looks about the same, except Romney ran closer to Obama all the way along.

But 2008 was different: McCain was ahead at first but slipped behind Obama to lose pretty badly.

For me, the interesting question is what this means about our civic culture and the purpose of campaigns and elections. The presidential candidates have raised about $1.3 billion so far and spent most of that on such activities as advertising, canvassing, and events. The press has spent untold billions on campaign coverage and commentary. All kinds of remarkable events have occurred. As all that has played out, citizens have been exhorted to pay attention and to change their opinions in response to arguments and information. But it looks as if almost everyone already had enough data 18 months ago to make up their minds. That includes me: nothing has transpired since June 2015 that has altered the probability of my voting for Clinton versus Trump by even one thousandth of a percentage point.

I used to subscribe to the view that the actions of candidates and campaigns matter, but they usually cancel each other out because all presidential nominees of major parties are effective campaigners. This year, we have one truly incompetent candidate, yet the trend remains flat. Unless you think that Clinton’s weaknesses cancel out Trump’s incompetence, it looks as if campaigns hardly matter at all. Once citizens know the candidates’ party labels, demographics, and basic facts about their biographies, they are ready to vote.

Perhaps Joseph Schumpeter was right, at least about presidential politics. It’s all about rendering a verdict on the status quo and choosing either the incumbent elites or an outsider. Schumpeter adds:

The reduced sense of responsibility and the absence of effective volition in turn explain the ordinary citizen’s ignorance and lack of judgment in matters of domestic and foreign policy which are if anything more shocking in the case of educated people and of people who are successfully active in non-political walks of life than it is with uneducated people in humble stations. Information is plentiful and readily available. But this does not seem to make any difference. Nor should we wonder at it. … Without the initiative that comes from immediate responsibility, ignorance will persist in the face of masses of information however complete and correct. It persists even in the face of the meritorious efforts that are being made to go beyond presenting information and to teach the use of it by means of lectures, classes, discussion groups. Results are not zero. But they are small. People cannot be carried up the ladder. …

Thus the typical citizen drops down to a lower level of mental performance as soon as he enters the political field. He argues and analyzes in a way which he would readily recognize as infantile within the sphere of his real interests. He becomes a primitive again. His thinking becomes associative and affective.

Since Schumpeter’s view of democracy is unattractive, we must either reform presidential politics or (if that seems impossible) write it off and focus on other aspects of our political system, where more people can show more “immediate responsibility” for collective decisions.

Pragmatic Local Intervention

Method: Pragmatic Local Intervention

Humanistic Data Visualization

Yesterday, I participated in “Visualizing Text as Data,” the inaugural discussion series from Northeastern’s NULab for Text, Maps, and Networks. We discussed Data Visualization in Sociology, by Kieran Healy and James Moody and Humaniti

Drucker writes:

…Graphical tools are a kind of intellectual Trojan horse, a vehicle through which assumptions about what constitutes information swarm with potent force. These assumptions are cloaked in a rhetoric taken wholesale from the techniques of the empirical sciences that conceals their epistemological biases under a guise of familiarity. So naturalized are the Google maps and bar charts of generated from spread sheets that they pass as unquestioned representations of “what it.”

Data visualizations – just like statical techniques – are an interpretation of the data, not a realization of the data. In the statistical world, there are known problematic techniques such as p-hacking where you find something significant only because you tried so many thing something (randomly) had to be significant. This is part of the art of data analysis – data fundamentally needs to be interpreted, but we should always be clear on what we’re interpreting, what assumptions we’re making in that interpretation, and what biases go into that interpretation.

Using a humanist lens, Drucker seems to apply a similar argument to visualizations. We are too accustomed to taking a visual representation of data as a ground Truth of what that data can tell us and to unaccustomed to thinking of visualization as a interpretation.

That’s not to say that visualization has no purpose, or that the fact that visualizations are interpretation is irreparably problematic.

There’s a great classic example of from Francis Anscombe – Anscombe’s quartet, as it’s appropriately called. Four data sets which appear comparable from their basic statistical properties, but which are obviously different when visualized.

But I don’t think that Drucker wants to throw visualization out all together. I read her article as a provocation – a reminder that visualizations, too, are interpretations of data.

Arguably, this reminder is even more important when were talking about visualizations rather than narrative or statistical descriptions. Those later modes almost inherently force a user to engage – to think about what they’re reading and what it means. Though there’s still plenty of misleading interpretation in the statistical world.

The real concern – and the one Drucker highlights so poignantly – is that we accept visualizations without question – we don’t spend enough time thinking about what boundaries a visualization should push.

In many ways this makes sense – we expect a visualization to be quickly and easily interpretable. But we are at risk of letting our biases run wild if we don’t question this. It may be easy for someone to interpret gender in a visualization if colors indicate pink for women and blue for men.

But please, please, don’t use this color scheme to encode gender. It may be interpretable, but it carries with it too much baggage of social norms. Far better to shake things up a bit.

Drucker pushes this argument to the extreme. Changing the gender color scheme is a relatively minor act of subversion, what happens if you take this questioning further? Make the user really work to understand the data?

This argument reminds me of the work of Elizabeth Peabody – who created intricate mural charts which could only be understood with a significant amount of time and energy. These visualizations were not “user friendly,” but at a time when women had few rights, they pushed the boundary of who gets to create knowledge.

This also reminds me of the arguments of Bent Flyvjerg, who argues that social science should stop trying so hard to be computational and should instead focus on phronesis – emphasizing a humanities, rather than computational, approach.

I’m not sure the two approaches are as mutually exclusive as Flyvbjerg fears, but his argument, like Drucker’s, raises a crucial point: it is not enough to ask “what is,” it is not enough to take computation as ground truth and – in terms of visualization – to take what is easy as what is good.

Regardless of field, we should be hesitant to put humanistic concerns aside, to think that facts can stand isolated from values. Values matter. Our assumptions and interpretations matter, and it may not always be most appropriate to try to bury our biases and try to pretend that they don’t exist.

Rather, we should bring them to the fore and examine them critically. Instead of asking “do I have any biases?” perhaps we’d do better ask ourselves, “do I have Good biases?”