Monthly Archives: April 2015

Life or Death

Last week, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was found guilty on 30 counts related to the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

The penalty phase of the trial begins today and may last for another four weeks. But the speculation has already begun: will Tsarnaev get the death penalty or life in jail?

To be honest, the death penalty seems unlikely.

I was surprised it was even an option since the State of Massachusetts found the practice unconstitutional in 1984.

Interesting, the reason given by the state supreme court at that time was that the death penalty “unfairly punishes defendants who choose to go to trial, since the death penalty could only be used after a guilty verdict at trial and not after a guilty plea.”

But, regardless of state policy, the Marathon bombing is a federal trial – making capital punishment an option.

In Boston, it’s not a popular option, though. A recent WBUR poll found that “only 31 percent of Boston area residents said they support the death penalty for Tsarnaev.”

Bill and Denise Richard, parents of the bombing’s youngest victim penned a compelling op-ed for the Boston Globe: “to end the anguish, drop the death penalty,” they wrote.

And they are not alone in speaking out in opposition to the death penalty. Jessica Kensky and Patrick Downes, who both lost limbs in the blast, issued a joint statement on the topic, writing, “If there is anyone who deserves the ultimate punishment, it is the defendant. However, we must overcome the impulse for vengeance.”

So no, death is not popular.

And given that the jury needs to be unanimous in its call for the death penalty, that result seems unlikely.

But is that enough?

Should those of us who fancy ourselves New England liberals, who pride ourselves on our compassion and informed rationality – should we breath a sigh of relief if the Tsarnaev verdict comes back: LIFE IN PRISON.

Is that enough to calm our restless spirits? To convince ourselves that while Tsarnaev may be a monster, we are not monster enough to kill him.

Life in prison. A just sentence for a 21-year-old kid who killed four people and wounded dozens of others.

Or is it?

160,000 people are currently serving life sentences in the United States, including about 50,000 who have no possibility for parole.

The Other Death Penalty Project argues that “a sentence of life without the possibility of parole is a death sentence. Worse, it is a long, slow, dissipating death sentence without any of the legal or administrative safeguards rightly awarded to those condemned to the traditional forms of execution.”

The ACLU of Northern California states that “life in prison without the possibility of parole is swift, severe, and certain punishment.”

Mind you, that’s an argument for why life sentences should replace the death penalty. The death penalty is outdated – even barbaric by some standards. Life without the possibility of parole is cleaner, neater.

A death sentence comes with “years of mandatory appeals that often result in reversal” while life sentences “receive no special consideration on appeal, which limits the possibility they will be reduced or reversed.”

And best, yet, a life sentence allows us to pat ourselves on the back for a job well done: our judgement was harsh but humane.

Our prisoner will get no appeals while he lives in extreme isolation – cramped in a 7 x 9 cell and fed through a slot in the solid steel door.

But at least he will have his life. We are progressive after all.

There is something wrong with this dynamic.

I’m not sure what to recommend in the Tsarnaev trial – whether life or death is ultimately a worse fate.

But more broadly we need to rethink our options. We need to recognize the deep, systemic failures of our prison system and identify new strategies and options for reparation and justice. If we want to be harsh, we can be harsh, but let’s be honest about what we are and what we want from our punishments.

After all, if we’re quibbling over whether someone should die slowly or die quickly – we’re hardly arguing about anything at all.

signal

Eight with twenty-one zeros. That’s how many

Letters and numbers, dots, jots, tittles and clicks

Our chatty species sent around this year–

More than in a score of generations past.

Into that wind-whipped Sonoran, I cast

These sixty grains, these quiet sounds I hear,

In hopes their mood or sense or purpose sticks

In the swirl that obscures so much and so many.

The post signal appeared first on Peter Levine.

New Research on Public Engagement Practitioners

This blog post was submitted by NCDD supporting member Caroline W. Lee, associate professor of Sociology at Lafayette College and author of Do-It-Yourself Democracy: The Rise of the Public Engagement Industry…

There has been a recent explosion of research interest in public engagement practitioners, much of which uses qualitative research methods and ethnography to capture the rich practices and processes in the field (see, for example, Oliver Escobar’s work here). In this vein, I wanted to share with readers of the blog about a symposium on public engagement professionals I participated in at the International Political Science Association conference in Toronto in July.

There has been a recent explosion of research interest in public engagement practitioners, much of which uses qualitative research methods and ethnography to capture the rich practices and processes in the field (see, for example, Oliver Escobar’s work here). In this vein, I wanted to share with readers of the blog about a symposium on public engagement professionals I participated in at the International Political Science Association conference in Toronto in July.

Organized by Canadian and French researchers Laurence Bherer, Mario Gauthier, Alice Mazeaud, Magalie Nonjon and Louis Simard in collaboration with the Institut du Nouveau Monde, the symposium was unique in that it brought together international scholars of the professionalization of public participation with leading practitioners of public participation from the US, UK, and Canada like Carolyn Lukensmeyer.

You can find the program schedule and more details about how to access the papers here. Topics covered participatory methods and strategies in a variety of public and private contexts in North and South America and Europe.

The organization of the symposium made use of participatory practices such as Open Space and a dialogic round table format bringing the scholars and practitioners together to comment on each others’ work. There was honest discussion at the symposium over the areas where practitioners and researchers might collaborate with and learn more from each other, and the areas where the goals and aims of researchers and practitioners may diverge. Of course, there was also acknowledgment that some researchers are also practitioners, although there seemed to be near universal rejection of the term “pracademic”!

Despite some tough criticisms of the results of participation efforts on the part of scholars, practitioners were extremely generous and open to debate. Simon Burall from INVOLVE and Peter MacLeod from MASS LBP in Canada both inviting interested researchers to study their organizations, practices, and processes in-depth (grad students, take note of this amazing opportunity!). Public engagement practitioners are eager to talk about the larger politics and micropractices of the field—even when some of the symposium attendees acknowledged that being subjects of ethnographic study was an odd and sometimes uncomfortable experience.

Despite the overview of exciting international research on participation, I left the conference with the sense that our work thus far has just scratched the surface of what it is like to be a democracy practitioner in a world of deep inequalities. The opportunities for additional research in the field and dialogue between researchers and practitioners are expanding—and even more essential at a time when participatory practices are proliferating across the globe.

For those interested in studies of the impacts of the public engagement field, many of the researchers at the IPSA Symposium have books on participation and deliberation coming out in 2015. Jason Chilvers has a volume coming out from Routledge with Matthew Kearnes entitled Remaking Participation: Science, Environment, and Emergent Publics. Genevieve Fuji Johnson’s book, Democratic Illusion: Deliberative Democracy in Canadian Public Policy, includes comparative case studies of “best case” deliberative efforts and their sometimes disappointing outcomes.

My own book, Do-It-Yourself Democracy: The Rise of the Public Engagement Industry, focuses primarily on participation professionals in the U.S. and how they manage D&D processes that are increasingly popular at times of economic crisis and retrenchment. For more on the prospects of all kinds of democratic participation in a landscape of economic and social inequalities, see my edited volume with Michael McQuarrie and Edward Walker, Democratizing Inequalities: Dilemmas of the New Public Participation.

The work of Laurence Bherer, Alice Mazeaud, and Magalie Nonjon presented at the conference looks more broadly at participation professionals in Europe and Canada, and is a valuable complement to prior work focused on Australian practitioners by Hendriks and Carson. Bherer is even organizing an edited volume with Mario Gauthier and Louis Simard on participation professionals in North America and Europe. The new French-language journal Participations has many articles that should be of interest to blog readers, as does the English-language Italian journal Partecipazione & Conflitto.

Do you know of new research on the growth of public engagement in the 21st century? If so, please share links in the comments!

pay-for-success in government

Let’s say you represent a program that would really save the government money as well as serving a social need. For instance, your program can cut the number of felonies, thereby saving $31,000 per person/per year in incarceration costs while reducing human suffering and injustice.

You’d like to ask the government for funds. You can’t get money from the executive branch at any level, because government budgets are committed to specific current activities, such as incarcerating a predicted number of inmates or fielding a certain number of police officers. Most agencies lack discretionary budgets for prevention, even if an investment would save them money later.

You could get funding from a legislative appropriation, but legislatures are not well set up to distinguish between truly effective preventive programs and those that just lobby well. In a crowded environment with tight budgets, your odds aren’t especially good.

You could offer the executive branch a contract that would commit the government to pay you from the savings that you actually achieve later on. They could measure the size of the savings using the most rigorous methods, such as random control groups. Then they could afford to pay you out of the savings in their planned budgets in future years.

But how can you operate your program until you deliver the savings and get paid? That apparent conundrum may have an answer: private third parties could invest in your program and get their money back–with a profit–once the government pays you for saving it money.

This is the pay-for-success model. Last week, we heard about it at a Tisch College panel with Jeffrey Liebman of the Harvard Kennedy School (the intellectual leader of this movement, who also provides technical support to governments); Molly Baldwin, Founder and CEO of Roca Inc., which has a pay-for-success contract to cut incarceration among highly at-risk young men in Massachusetts; Jeff Shumway of Social Finance, who sets up these deals; and Brian Bethune of the Tufts Economics Department and a Tisch College Faculty Fellow for 2015-16.

The evidence seemed compelling that Roca will save Massachusetts money while helping young men get on a better track. But I am a civic engagement/democratic participation guy, so I am supposed to ask, “Where are citizens in all of this?” I would say the following:

First, pay-for-success is value-neutral. It is an efficiency measure that could be used for a wide range of purposes. A dictatorship could use it to round up human rights protesters more effectively. Reducing incarceration in Massachusetts sounds much better than that, yet it could possibly legitimize the prison system. I don’t really agree with that critique, but I would acknowledge that any social intervention is a value choice. As such, it should be informed and reviewed by the public.

We already have the power to elect the high officials who preside over Massachusetts’ state government. But an election presents a binary choice (the Republican or the Democrat), which is a crude device for influencing subtle choices, such as whether to fund Roca, Inc. We can lobby and advocate on such matters, but there is an inevitable tendency for most advocates to be biased by self-interest or strong ideology. So we need more deliberative forms of civic engagement that get a wider range of people involved in making difficult value choices.

But increasing civic engagement seems fully compatible with using a pay-for-success model to get the government’s own job done. In fact, pay-for-success is wonderfully transparent. If citizens are asked to pay for 10,000 jail cells, we have no way of knowing how that will affect crime, safety, or fairness. But we can review the Roca, Inc. agreement and decide whether it offers what we want. And we don’t pay a dime unless it delivers.

A different question is how citizens should be involved in the programs themselves. I would hypothesize that in general, programs that produce good results have been designed and built through collaborations that involve the affected communities. Social policy is not like medicine, where chemical compounds that were invented in labs can cure (some) diseases in the real world. Social interventions operate in complex contexts with lots of conflicting values and interests, so they typically work only if they have been co-constructed. That is true, by the way, of Roca; Molly Baldwin emphasized that youth in the program have influenced its design.

Finally, if you want a robust democracy, one element has got to be a reasonably effective government that is capable of delivering what the people choose after due reflection. Eighty years after the New Deal, the US welfare state is not well designed for that purpose. It can’t, for example, make sensible investments in prevention. Even when it pays for activities that should have preventive effects (such as education), it doesn’t pay for success; it just funds the activities, some of which are ineffective. So I believe that pay-for-success is one step toward restoring confidence in government as the people’s instrument. Confidence is not an end in itself, but it is an important means to reengaging citizens in public life.

But see also: “qualms about a bond market for philanthropy”, “can nonprofits solve big problems?” and “innovation and civic engagement.”

The post pay-for-success in government appeared first on Peter Levine.

What is Public Engagement and Why Do It? (ILG)

This five-page tip sheet guide from Institute for Local Government, What is Public Engagement and Why Should I Do It? (2015), has two major sections: part 1 puts forth public engagement terms to help local officials find which approach “fits” best and part 2 gives benefits of engaging the public. Download the PDF for free here.

From the guide…

Six definitions are given for public officials to better understand which approach is the most appropriate to use: civic engagement, public engagement, public information/outreach, public consultation, public participation/deliberation, and sustained public problem solving.

Why Engage the Public?

- better identification of the public’s values, ideas and recommendations

- more informed residents- about issues and about local agencies

- improved local agency decision-making and actions, with better impacts and outcomes

- more community buy-in and support, with less contentiousness

- more civil discussions and decision making

- faster project implementation with less need to revisit again

- more trust in each other and in local government

- higher rates of community participation and leadership development

About the Institute for Local Government

The Institute for Local Government is the nonprofit research education affiliate of the League of California Cities and the California State Association of Counties. Its mission is to promote good government at the local level with practical, impartial and easy-to-use resources for California communities. The Institute’s goal is to be the leading provider of information that enables local officials and their communities to make good decisions. Founded in 1955, the Institute has been serving local officials’ information needs for 55-plus years. Some of the highlights of that history are detailed in the story below. While respecting and honoring its past, the Institute is also intently focused on the present and future. In these difficult economic times, the need for the Institute’s materials for local officials is even greater.

Follow on Twitter: @InstLocGov.

Resource Link: www.ca-ilg.org/document/what-public-engagement

Confab Call with Pete Peterson is THIS Thursday, 4/23

We are excited to be gearing up for NCDD’s next Confab Call this Thursday, April 23rd! Are you ready to join us? The call will take place from 1-2pm Eastern/10-11am Pacific.

As we recently announced, this week’s Confab will feature a conversation with NCDD Member Pete Peterson. Pete is the Executive Director of the Davenport Institute for Public Engagement and Civic Leadership, and in 2014, he ran for California Secretary of State on a platform of increasing informed civic participation and using technology to make government more responsive and transparent.

As we recently announced, this week’s Confab will feature a conversation with NCDD Member Pete Peterson. Pete is the Executive Director of the Davenport Institute for Public Engagement and Civic Leadership, and in 2014, he ran for California Secretary of State on a platform of increasing informed civic participation and using technology to make government more responsive and transparent.

On this Confab, Pete will share lessons learned from running for office on a platform he described as becoming California’s first “Chief Engagement Officer,” and what promise and challenges the civic participation field faces when translated into a political context.

NCDD’s Confab Calls are great opportunities to talk with and hear from innovators in our field about the work they’re doing, and to connect with fellow members around shared interests. Membership in NCDD is encouraged but not required for participation in these calls.

There’s still time left to get signed up, but don’t delay! Register today and save your spot! We look forwarding to having you join us for this wonderful conversation.

Tisch College Names Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg New Director of CIRCLE

I am thrilled to share that my colleague Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg was recently named director of CIRCLE – Tisch College’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement.

Kei is honestly one of the smartest people I know. With a Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology with Specialization in Children and Families, she brings a critical development perspective to the work.

I’ve had the pleasure of working with her for nearly seven years and in that time I have learned so much from her insights. She is a true leader and I’m so excited to see the next phase of CIRCLE’s life.

You can read the formal announcement of her appointment here.

Better, Not More — aka Buen Vivir

Here is an inspiring five-minute video about the quest for a new post-growth economic system. "Better, Not More," was produced by Kontent Films for the Edge Funders Alliance, and was released last week at a conference in Baltimore. The video is a beautiful set of statements from activists around the world describing what they aspire to achieve, especially by way of commons.

The vocabularies and focus for the idea of "better, not more," obviously differ among people in one country to another. Buen vivir is the term that is more familiar to the peoples of Latin America, for example. But as the growth economy continues its assault on the planetary ecosystem, cultivating an ethic of sufficiency -- and developing the policies and politics to make that real -- is an urgent challenge.

the Millennials’ political values in context

The General Social Survey asked a set of questions about political values or principles twice, in 2004 and 2014. The questions were phrased, “How important is it ….?” and the items included: always to obey the law, always to vote, never to try to evade taxes, and always to understand other people’s reasoning. Respondents were also asked how important it is for people to be able to participate in making decisions. It’s a nice mix of conventional civic obligations and deliberative and participatory values.

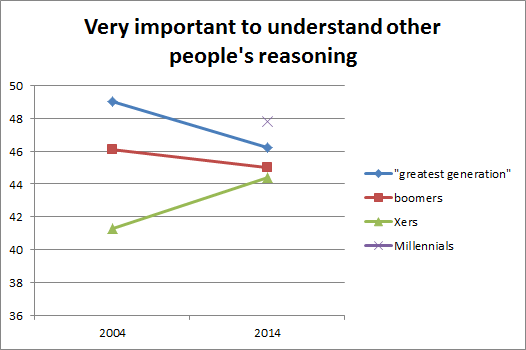

As is my wont, I have looked at the changes generationally. Graphs are helpful for visualizing these changes. For instance, the first graph below displays an interesting pattern in attitudes towards understanding other people’s reasons. Generation Xers have become substantially more committed to this value as they (or I could say “we”) have aged, although we still lag a bit behind our elders. Older Americans have lost their commitment somewhat, especially the group that was born between 1926 and 1945. Millennials enter the picture with the highest levels of support currently, although they rate listening as less important than their grandparents did a decade ago.

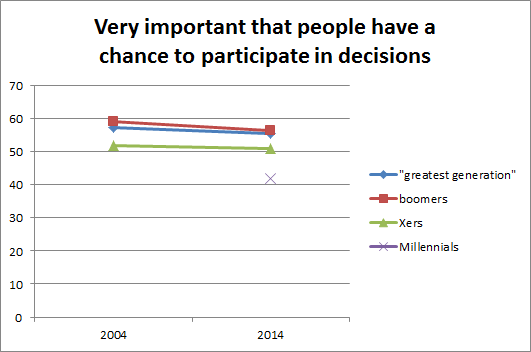

I’ll display a second graph that shows quite a different pattern. The younger you are today, the less likely you are to believe that it’s very important for people to be able to participate in decisions. At least since 2004, the older cohorts have not changed their minds on that topic. Millennials continue the pattern of declining support by entering adulthood with the lowest levels of commitment to the value or principle of participation. This graph suggests that unless we do something to change the trends, generational replacement will gradually lessen our commitment to participation.

The pattern for always obeying the law looks like the second graph above, although the gaps are smaller. Millennials seem less committed than their predecessors, which could reflect an openness to civil disobedience.

All the older cohorts have grown to oppose tax evasion more as they have aged. Millennials enter the picture least committed to that ideal, but they are just where the Xers were a decade ago, and it’s possible that people’s focus on this topic naturally grows as they age.

Voting, finally, shows a pattern like participation in decisions (the second graph above). Commitment is lower for each generation, and much lower for Millennials. The older generations did not change their minds between 2004 and 2014, but the shrinking of the pre-War cohort and the growth of Xers and Millennials pushes down the average for the population as a whole. Voting is becoming less of a perceived obligation due to generational replacement. However, it’s important to note that this is a question about the obligation to vote. Actual voting rates have been flat over time. In other words, Millennials vote at similar rates to their predecessors; they are just less likely to conceive of that action as a duty.

The post the Millennials’ political values in context appeared first on Peter Levine.