Bilancio partecipativo 2016 Comune di Mira [Mira participatory budget]

The Shams El-Bir Association Community Committee in El-kfoor Village, El-Minia, Upper Egypt

Focus Group

Method: Focus Group

Veneto in bicicletta. Opportunità per gli operatori turistici [Veneto by bike. Opportunities for tourism

Science and Technocracy

Reading Warren Weaver’s 1948 article, “Science and Complexity,” I was struck by his description of science and his impassioned argument for its importance:

Science clearly is a way of solving problems – not all problems, but a large class of important and practical ones. The problems with which science can deal are those in which the predominant factors are subject to the basic laws of logic, and are for the most part measurable. Science is a way of organizing reproducible knowledge about such problems; of focusing and disciplining imagination; of weighing evidence; of deciding what is relevant and what is not; of impartially testing hypothesis; of ruthlessly discarding data that prove to be inaccurate or inadequate; of finding, interpreting, and facing facts, and of making the facts of nature the servants of man.

Increasingly, we seem to live in a “post-factual” era, where experts are maligned as mere technocrats; where knowledge is dismissed as perspective.

There are good arguments against technocracy: history has numerous examples of the dangers of sidelining personal experience in favor of detached technical expertise. But science is not technocracy. We can embrace science, embrace facts, without resorting to a totalitarian technocratic system. As Weaver writes:

Yes, science is a powerful tool, and it has an impressive record. But the humble and wise scientist does not expect or hope that science can do everything. He remembers that science teaches respect for special competence, and he does not believe that every social, economic, or political emergency would be automatically dissolved if “the scientists” were only put into control.

Can Public Life Be Regenerated?

The 32-page report, Can Public Life Be Regenerated? (2016), was written by David Mathews and supported by the Cousins Research Group of the Kettering Foundation. This report is based on a presentations Mathews gave the the Independent Sector conference on issues of community, civil society, and governance. In this report, Mathews explores the possibilities to “reweave the social fabric” within society, to improve its social capital and revitalize its sense of community, and create a healthier civil society.

Below is an excerpt of the report and it can be found in full at the bottom of this page or on Kettering Foundation’s site here.

From the guide…

Foreword

This paper was written in 1996 for an Independent Sector conference. At that time, the term public life was used to distinguish political life from other kinds of collective living. This was intended to counter a tendency to conflate largely social phenomena (attending a picnic) with more political activities (building a playground to give children a safer place to play). If I were writing this paper today, I likely would title it Can Democracy Be Regenerated? The Kettering Foundation’s research has led to a distinctive understanding of democratic politics that puts citizens at the center. By citizens, we mean people who join with others to produce things that serve our common well-being. As our research evolved, we came to use “making democracy work as it should” as a central, organizing theme. We define democracy, at its most fundamental, as a system of governance in which power comes from citizens who generate their power by working together to combat common problems—beginning in their communities—and by working to shape their common future, both through what they do with one another and through their institutions. – David Mathews April 4, 2016

These days we seem willing to consider the possibility that democracies need something more than written constitutions, multiple parties, free elections, and representative governments. They also depend on a strong public life, a rich depository of social capital, a sense of community, and a healthy civil society. Now comes the obvious follow-up: Is it possible to “reweave the social fabric,” to generate social capital where it is lacking, to build a sense of community in a fragmented, polarized city, to invigorate public life at a time when many Americans are seeking security in private sanctuaries? No one knows. Maybe a democratic civil society takes centuries to develop, building layer upon layer like a coral reef. Maybe the places we admire most result more from happenstance than we would like to admit. These reservations notwithstanding, we do have cases where a civil order changed its character in a relatively short period of time. Modern Spanish democracy emerged from Franco’s fascism in only a few decades, according to Víctor Pérez Díaz. And Vaughn Grisham Jr. reports that Tupelo, Mississippi, changed its civic character in roughly the same amount of time, the result being that the poorest city in the poorest county in the poorest state of the union became a progressive community with a per capita income close to that of Atlanta.

So maybe—just maybe—it is possible for towns and cities, perhaps even counties and states, to change their politics. Maybe public life can be regenerated. I say “regenerated” because I am assuming that some vestige or memory of public life exists almost everywhere. I think modern public life is rooted in the earliest institutions and norms created for collective survival. So my instincts tell me that strengthening public life is best accomplished by following the advice of J. Herman Blake, a very effective community organizer, whose practice is to “build on what grows.” With that as a predicate, I want to go on to the question of how people might change the character of their civil order. There is some urgency surrounding this question; I sense a danger in trying to strengthen public life with only a thin concept of the public, civil, or communal to guide the way. That would create a problem akin to trying to paint a barn red without clearly distinguishing red from pink or orange. There is a tendency to take descriptions of cities with a rich reservoir of social capital and try to replicate their features. If they have a lot of festivals, why not generate public life with a pig roast? (Actually, a foundation in Europe was asked to do just that.) But are community barbecues and festivals the product of something that happens prior to the events, of some precondition that we haven’t been able to identify? Are we in danger of mistaking the symptom for the cause? If we do, our strategies for building civil society will be the equivalent of dress-for-success strategies that tell us we can get ahead in the world by wearing the right tie or dress.

Developing a Concept of Public Life

Here is what I will try to do in this paper: Drawing on what the Kettering Foundation is learning from its research and observations, and from studies others have done, I will propose a way of thinking about public life, or a paradigm.5 Kettering has been developing a hypothesis about what public life is in order to have a better idea about how to strengthen it. The way we understand the structure and function of a public suggests ways to regenerate public life. Since no one knows the answer to the question of whether such life can be renewed, surely the thing to do is to spell out our assumptions, which can be tested by experience.

The Influence of Studies of Social Capital and Community Development

We aren’t making empirical claims when we develop a hypothesis. Yet our experiences influence our imagination of what might be. For 15 years, Kettering has been observing public life in communities from Grand Rapids, Michigan, to El Paso, Texas, and from Newark, New Jersey, to Orange County, California. We have also commissioned independent research on public life. And we have been influenced by studies like Pérez-Díaz’s on Spain, Grisham’s on Tupelo, Robert Putnam’s on north central Italy, and that of the Heartland Center for Leadership Development on the difference between dying and prospering rural communities, among others. Putnam and Grisham reinforced our own impressions that the “soft side” of the social order or an intangible such as social capital is critical to public life. Social capital is said to consist of networks of civic associations, along with norms of reciprocity and social trust, that result in high levels of voluntary cooperation. This capital is generated where public life is strong, that is, where people are involved in public matters and in relationships that run horizontally (among equals) instead of vertically (between haves and have-nots). As you know, while Putnam found these characteristics in some areas in Italy, they were noticeably absent in others. People in the “uncivil” areas did not participate in either local politics or social organizations, and their relationships tended to be hierarchical, with the have-nots dependent on the haves.

This is an excerpt of the report, download the full guide at the bottom of this page to learn more.

About Kettering Foundation

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

Follow on Twitter: @KetteringFdn

Resource Link: www.kettering.org/catalog/product/can-public-life-be-regenerated

Engaging Ideas – 1/27/2017

why Trump fans aren’t holding him accountable (yet)

(Washington DC) Kevin Drum imagines how a Trump fan receives the president’s tweets:

You’re at home, watching the Factor, and O’Reilly is going on about the crime problem in Chicago. It’s outrageous! The place is a war zone! Somebody should do something!

Then, a few minutes later, you see Trump’s tweet. “If Chicago doesn’t fix the horrible “carnage” going on, 228 shootings in 2017 with 42 killings (up 24% from 2016), I will send in the Feds!” Damn straight, you think. They need the National Guard to set things straight there. Way to go, President Trump.

This exchange is good enough for you–on its own. You don’t really want Trump to send the feds into Chicago, whatever that might mean. If it would cost money or create a precedent for federal intervention in your town, or anything like that, you might actually be against it. But your media stream will never give you an update on whether Trump sent in the feds or what happened to the murder rate in Chicago. You are immersed in media that consists largely of bad news about places you don’t like. You are satisfied that the guy in charge shares your opinion and has announced he’s on it. He even quotes verbatim the same stats you just saw on O’Reilly. It’s a magic solution–at last.

I think more or less the same will happen as a result of Trump’s announcement today that Mexico will pay for the border wall via a 20% import tax. That is highly unlikely to occur, because Congress would have to enact the tax, and I’m guessing the economic effects would be awful if it did; but Trump’s fans will probably never get an update. They may hear about battles between the president and Congress over taxes, but those will take the form of specific insults flung from his end of Pennsylvania Ave. up to the Hill, which they will endorse. Each exchange will be an event unto itself.

I happen to think that this kind of politics has yuge political limitations for Trump. Most people already disapprove of him, and his welcome is going to wear even thinner when people’s actual lives fail to improve. In turn, massive disapproval will weaken his already shaky position. But it’s still a very dangerous situation, at best, and is very far from any reasonable model of a democracy.

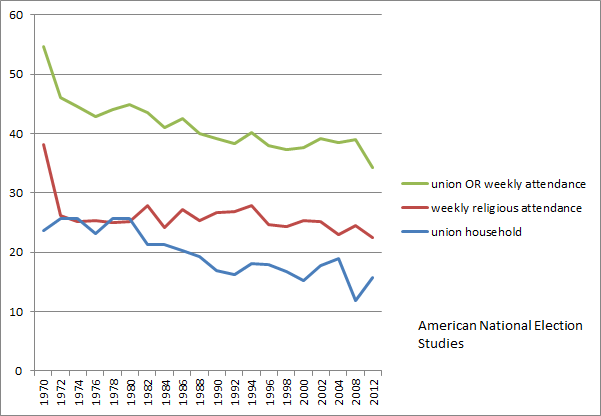

My explanation is that millions of Americans have lost all expectation that leaders will be accountable to them. At the national level, they are not getting very good results from the government that purports to represent them. At the local level, they have lost the kinds of institutions that used to depend on people like them. To reprise a graph from a recent post, here is the trend in the proportion of people who belong to a church and/or a union:

For all their flaws, these are the kinds of institutions that make promises and then have to deliver. If they fail, their members know about it and complain, act up, or walk out. A union or a church has a real covenant with its members. When people have no such expectations of accountability, they are much more likely to be satisfied because the boss just tweeted something they agreed with. Again, I think Trump’s own appeal will wear even thinner than it is now, but the underlying problem is a lack of accountable organizations in many communities.

Demanding Dignity and Respect for All My Neighbors

It’s been a dramatic week. President Trump has signed a number of Executive Orders and Memoranda which strike at the very core of what I believe.

I have been particularly disturbed by two orders signed yesterday; the first on “border security” and the other on “public safety” – phrases which are essentially Newspeak for racial bias and immigrant hatred. “Tens of thousands of removable aliens have been released into communities across the country,” one order claims.

I am ashamed to hear such hateful rhetoric coming from the President of my country.

But I am given hope by the millions of good men and women who don’t accept such false claims; who have worked and who reaffirm their work to supporting and welcoming all members of our community.

In his Order, President Trump claimed that sanctuary cities – those jurisdictions which have refused to enable a Federal witch-hunt for difference, “have caused immeasurable harm to the American people and to the very fabric of our Republic.”

I say that it is these jurisdictions which epitomize the very fabric our Republic. It is these jurisdictions which stand true to American values; who pursue the vision of a land where all people are created equal and endowed with the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

I am proud to live in a Sanctuary city, and I am proud that my mayor, Joseph Curtatone, has said in no uncertain terms that we will not waiver in this commitment. These are our neighbors.

I am also proud to serve as the vice-Chair of the board for The Welcome Project, a vibrant non-profit which builds the collective power of Somerville immigrants to participate in and shape community decisions.

In response to Wednesday’s reprehensible executive orders, The Welcome Project released the following statement this morning. And by the way, you can donate to The Welcome Project here. ___

President Donald Trump signed executive orders Wednesday attacking America’s status as a nation of immigrants. We at The Welcome Project are saddened but steadfast. We will not waiver in continuing the work our communities have entrusted us to do; building the collective power of immigrants to help shape community decisions and pursuing the American vision of liberty and justice for all.

We thank Mayor Curtatone, the Board of Aldermen, and the residents of Somerville as they continue to fight for America and support immigrants, community, and Sanctuary City status. Somerville continues to be a beacon of light and a hope for many. We know that our community only becomes stronger when all people are free to participate in it; that Sanctuary Cities are not about harboring criminals, they are about reducing crime, increasing trust between the police and the community, and offering a better future for our families.

The Welcome Project will continue to work with all members of our community, supporting all immigrants regardless of documentation status. We will stay vigilant in our mission and push for the rights of all. We will work with the immigrant community to ensure their voices are being heard. We will continue our commitment to justice, equality, and inclusion. We thank all of you for your continued support as we explore the effects these executive orders have on our organization, our constituents, and our city.

Benjamin Echevarria

Executive Director