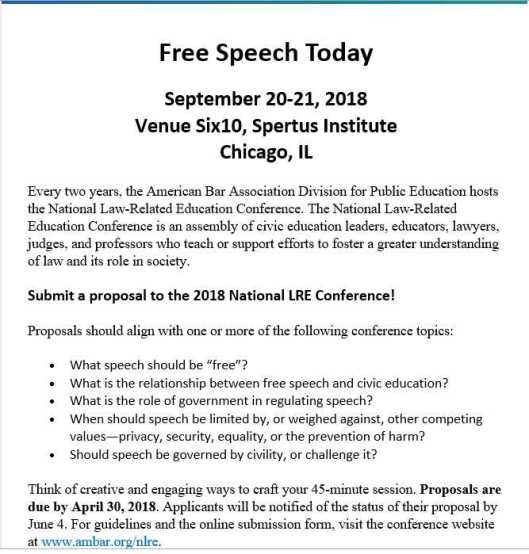

2018 National Law Related Education Conference

Free speech, in this era of ongoing partisan rancor, has never been more important. The theme of this year’s National Law Related Education Conference (a project of the American Bar Association) is, in fact, that idea of free speech. What is it, and why does it matter? As educators, especially as civic educators, these are questions, this is a theme, that matters to us. If you have the opportunity, please consider submitting a proposal to the upcoming conference. The call for proposals is below, but you can also learn more here.

Be sure to also check out the great resources of our partners in civic education, like the ABA, shared through the Civics Renewal Network!

what if something is not your problem?

I frame a most of my research and teaching around the question, “What should we do?” I’d even define a citizen as someone who asks that question. In academic contexts, I argue that this question is complex and under-theorized: it raises difficult issues of loyalty, complicity, the definition of groups, dynamics within groups, problems of collective action, etc. These issues deserve attention along with the more typical questions of political theory: “What is justice?” and “Why do things happen as they do?” The citizen’s question is also central to our new Civic Studies major at Tufts.

However, insisting on this question may imply that everyone bears primary responsibility for addressing every issue. What if you are the victim of a social injustice that someone else has created or has the best opportunity to remedy? Then it is most important for them to decide what they are obliged to do to improve your situation. Not every problem is your problem.

Nevertheless, “What should we do?” remains an important question for virtually all of us. Even if the main moral responsibility lies with someone else, the only thing we can control is what we do.

We may decide that we should demand justice from another person or group, but making a demand is also a form of action that we choose to take. In fact, making demands on “target authorities” is the characteristic activity of social movements; and social movements are composed of people who ask “What should we do?” It’s just that their goal is to to compel other people to take more responsibility.

Finally, acting is not merely a price we must pay in order to improve the world. It can also be a benefit that we reap, since exercising agency can be an aspect of a good life. Although we should encourage–and sometimes even compel–other people to ask what they should do, it is also worth asking that question on our own behalf, regardless of our circumstances.

See also: a sketch of a theory of social movements; what should we do?

Insights on Participatory Democracy via the Jefferson Center

NCDD member org, The Jefferson Center, recently shared their recap of the Innovations in Participatory Democracy conference that happened last month. In their reflections, they discuss the future opportunities for our democracy by better bringing together participatory principles and deliberative approaches. You can read the post below and find the original on Jefferson Center’s site here.

Making Participation More Deliberative, and Deliberation More Participatory

A few weeks ago, we attended the Innovations in Participatory Democracy Conference in Phoenix, Arizona. The conference, which we were excited to support as both participants and presenters, brought together community leaders, government officials and staff, practitioners, researchers, funders, youth leaders, and technologists to explore innovations in government participation.

A few weeks ago, we attended the Innovations in Participatory Democracy Conference in Phoenix, Arizona. The conference, which we were excited to support as both participants and presenters, brought together community leaders, government officials and staff, practitioners, researchers, funders, youth leaders, and technologists to explore innovations in government participation.

We led a workshop on Citizens Juries, Assemblies, & Sortition, and participated in a panel on the similarities and differences across participatory budgeting, Citizen Juries, and citizen assemblies. While we were there, we saw democracy in action at Central High School, where students are part of a current Participatory Budgeting Project initiative.

At the conference, it was clear the opportunities for participatory democracy are expanding. Participatory democracy is made up of two key parts: participatory principles, which often invite the public to share their thoughts and opinions, and deliberative approaches, which typically convene a smaller group of individuals to learn about an issue and create plans for action or policy recommendations. While these two unique approaches are sometimes thought of as opposing forces, we saw how people around the world are using both to make democracy more impactful and inclusive. There’s no longer one clear set of principles for the “right” way to participate in democracy, and it’s incredible to be part of this movement.

We wanted to share a few exciting outlooks for democracy that we took away from the conference:

1. Collaboration with governments will grow and change

In the United States, Citizens Juries and mini-publics are typically run by nonprofits (like us!), rather than officially sponsored by the national government. This is changing as governments are exploring new ways to engage with their citizens. But, that doesn’t mean the only outcomes of deliberation and participation need to be policy changes: we’ve learned throughout our work that participatory democracy can be used successfully for long-term, community-wide impacts.

At the conference, we shared the example of our Rural Climate Dialogue program in Winona County, where residents created recommendations for their community to adapt to climate change and extreme weather. Since the dialogue, the City of Winona has adopted an energy plan with goals to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. They’ve also invested in community education initiatives on energy efficiency and water savings. Urging policy changes while supporting long-term behavior changes, like we’re doing in Winona County, will help governments, their partners, and citizens sustain the results of engagement efforts.

2. It’s time to focus on the opportunities to combine participatory and deliberative approaches

By merging both participatory principles and deliberative approaches, we can make democracy more accessible and impactful. You might be familiar with the thoughts of Micah Sifry, of Civic Hall, on these two distinct tactics: “Thick engagement doesn’t scale, and thin engagement doesn’t stick”. Deliberation (thick engagement) can be productive, but needs lots of time and resources. Participatory approaches (thin engagement), like asking for input on social media, may be easier and quicker, but require little ongoing involvement or further opportunities for deeper engagement, as Matt Leighninger of Public Agenda explores. But, there’s a solution, and we saw countless examples of this at the conference: we can invite people to submit ideas and proposals online for consideration by participants who are meeting in person. Conversely, we can build on the recommendations and ideas generated at deliberative events to form the base of digital participation efforts.

We’ve been testing out this combined approach in a few different projects. Through Your Vote Ohio and Informed Citizen Akron, we used deliberative events to ask citizens in Ohio what they needed from their local news organizations. Their input set the stage for Your Voice Ohio, a project that explores community engagement approaches to help newsrooms across the state listen and respond to their audiences. With the deliberation recommendations as a guiding force, we host open community events, invite people to share their stories online and through social media, and are rolling out Hearken as a platform where local residents can ask reporters questions about the addiction crisis. By combining these forces we’re making democracy more accessible to everyone.

3. The entry to engagement is different in every community

One of the incredible projects we heard about was the Participatory Budgeting Project’s work with the Phoenix Union High School District, where they invited student input to decide how to spend district-wide funds. This was the first school participatory budgeting process in the U.S. to focus on district-wide funds, which started with five public high schools and has expanded since. While this may seem like a small step, this has begun to shift the relationship between students and administrators.

Administrators are now considering how they can adapt these participatory practices to the everyday culture of these schools, like inviting students to share their thoughts on changes such as scheduling and course offerings. Because the initial opportunity to participate was simple and manageable for both the students and the administration, they’ve laid the foundation for future collaboration and growth. Plus, young people got to use real voting machines in the process, which was a great opportunity to experience how voting and live democracy actually work. We’re excited to see how this can expand to other schools and communities.

4. Success means equipping others

In democracy work, we often focus on “bringing projects to scale”. This is important, but we also don’t want to leave communities behind without equipping them with the tools they need for sustained success. For too long, the dominant theory of change for deliberative democracy looked something like this:

- Select a topic

- Host a Citizens Jury (or other deliberative event)

- Generate a report

- Hope someone reads it and utilizes the recommendations.

But, we can do so much more. We can combine thick and thin engagement techniques to give people the resources to continue projects after engagement organizations and professionals leave the community. At the Jefferson Center, we are implementing this approach with our dialogue-to-action model. First, we co-define: we build relationships with stakeholders and community members to gain a deeper understanding of the issue at hand. Next, we co-design: working with project partners, we develop and implement an engagement process to unleash creative ideas which also provides participants with the expertise, tools, and time they need to develop solutions. Finally, we co-create: our partners use the public input to advance local actions, reform practices and processes, and guide policy development and decision-making.

5. We can frame impact differently to support broader results

Deliberation and participation can be misunderstood as having one narrow goal: to influence a policy decision. But instead, we can evaluate the success of Citizen Juries, mini-publics, and other engagement efforts not just by their policy influence, but by the opportunities to impact individuals, communities, networks, organizations, and governments. Unless they are expressly commissioned by a government sponsor, the projects that go beyond one policy objective will likely have the most impact. By taking a more holistic approach to change, we can build sustainable partnerships between individuals, leaders, local institutions, the media, and others, who can carry on the important work in the community.

For instance, Participatory Budgeting Projects don’t just enable people to direct public money to community priorities. Throughout the process, community organizations and networks are strengthened, as groups work together to focus on their shared needs. After the discussion ends, these groups may form new organizations and partnerships and continue positive and constructive engagement. All of the PB award winners at the conference, Cyndi Tercero-Sandoval (Phoenix Union High School District), Sonya Reynolds (Participatory Budgeting NYC), and Cecilia Salinas (Participatory Budgeting Chicago in the 49th Ward) represent this investment in long-term impact.

Looking forward

Participation and deliberation should not be positioned as opposing forces. Instead, it’s time to identify meaningful opportunities to make participatory practices more deliberative, and make deliberative processes more participatory. For those of us committed to democratic reform and innovation, combining these elements effectively, regardless of the issue, method, or context, will support our ambitions to create a stronger, more vibrant democracy for all of us.

You can find the original version of this post on Jefferson Center’s blog at www.jefferson-center.org/making-participation-more-deliberative-and-deliberation-more-participatory/.

Testing Assumptions in Deliberative Democratic Design: A Preliminary Assessment of the Efficacy of the Participedia Data Archive as an Analytic Tool

The 31-page article, Testing Assumptions in Deliberative Democratic Design: A Preliminary Assessment of the Efficacy of the Participedia Data Archive as an Analytic Tool (2017), was written by John Gastil, Robert C. Richards Jr, Matt Ryan, and Graham Smith and published in the Journal of Public Deliberation: Vol. 13: Iss. 2. In the article, the authors discuss how deliberative process design affects participants and the resulting policy, they then tested their hypotheses using case studies from Participedia.net, and finally offer implications for their theory. Read an excerpt of the article below and find the PDF available for download on the Journal of Public Deliberation site here.

From the introduction…

Experiments with new and traditional modes of public engagement have proliferated in recent years (Warren, 2009). In attempting to make sense of this shift in contemporary governance, democratic theorists, political scientists and participation practitioners have drawn inspiration from deliberative democratic theory (Nabatchi et al., 2012). From this approach, the legitimacy of political decision making rests on the vitality of public deliberation amongst free and equal citizens (Bohman, 1998).

A considerable body of research attempts to analyze the design, process, and consequences of exercises in public engagement from a deliberative perspective, with particular focus on randomly selected mini-publics (e.g., Fishkin, 2009) and participatory budgeting (e.g., Baiocchi, 2005). These designs, however, represent only a small proportion of the diverse universe of democratic innovations. Design features vary considerably among such processes, including the priority given to promoting deliberation amongst participants.

No official records, census, or statistics capture the presence of democratic innovations, let alone the kind of data necessary to test the robustness of assumptions within deliberative democratic theory. Researchers tend to be limited to case studies, often of exemplary cases that skew our expectations of democratic innovations. Larger comparative studies are generally within-type, such as among Deliberative Polls (List et al., 2013), Citizens’ Initiative Reviews (Gastil et al., 2016), and participatory budgeting (Sintomer et al., 2012; Wampler, 2007) or within the same political context (Font et al., 2016). Analysis across types and context (geographic and political settings) is relatively rare, since the level of resources required to collect the necessary cases is prohibitive.

The development of Participedia opens up the possibility of such analysis. Participedia (http://participedia.net) is a research platform that exploits the power of self-directed crowdsourcing (Bigham et al., 2015) to collect data on participatory democratic institutions around the world. It is designed explicitly to enable researchers to compare data meaningfully across types and settings, recognizing that such data is held by a diverse group of actors, who organize, sponsor, evaluate, research, or participate in democratic innovations. Participedia has existed since 2009 and currently hosts systematised information on in excess of 650 cases. With the support of a CA$2.5 million, five-year Partnership Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), the coverage of cases globally will continue to increase rapidly.

This paper exploits the already available data from Participedia to offer the first systematic analysis across a wide variety of political contexts and types of democratic innovations to explore the relationships among design characteristics, deliberative process quality, and impacts on policy and participants. We begin with an account of a stylized input-process-output model intended to capture the relevant core assumptions of deliberative theory. The next section describes the Participedia project and platform in more detail, highlighting how it has been designed to allow the testing of deliberative and participatory theories across a range of cases developed in very different contexts. In the methods section that follows, we explain the challenges faced in coding effectively the Participedia data to accord with our model. This has necessitated not only the use of fixed data from the platform, but also content analysis of case descriptions while overcoming challenges of low levels of inter-coder reliability and missing data. The results show that there are interesting patterns of associations that emerge from the Participedia data. Many of these findings reinforce existing assumptions about the relationship between design, process, and impact, but some may surprise readers and warrant future investigation. We conclude with reflections on the implications of our findings for deliberative theory, our understanding of the design of democratic innovations, and the efficacy of Participedia as a method of generating comparable data in this field of study.

Download the full article from the Journal of Public Deliberation here.

About the Journal of Public Deliberation![]()

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen-friendly form.

Follow the Deliberative Democracy Consortium on Twitter: @delibdem

Follow the International Association of Public Participation [US] on Twitter: @IAP2USA

Resource Link: www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol13/iss2/art1/

Man AND Rabbit: Naturalizing the Ethics of Belief

Philosophers sometimes pretend that truth-seeking is a foundational epistemic norm, and that everything else–especially ethics, politics, and culture–must be subordinated to it. CS Lewis put it this way in an essay on whether Christianity will make us happy and good:

“‘Can you lead a good life without believing in Christianity?’ This is the question on which I have been asked to write, and straight away, before I begin trying to answer it, I have a comment to make. The question sounds as if it were asked by a person who said to himself, ‘I don’t care whether Christianity is in fact true or not. I’m not interested in finding out whether the real universe is more like what the Christians say than what the Materialists say. All I’m interested in is leading a good life. I’m going to choose beliefs not because I think them true but because I find them helpful.’

Now frankly, I find it hard to sympathise with this state of mind. One of the things that distinguishes man from the other animals is that he wants to know things, wants to find out what reality is like, simply for the sake of knowing. When that desire is completely quenched in anyone, I think he has become something less than human. As a matter of fact, I don’t believe any of you have really lost that desire. More probably, foolish preachers, by always telling you how much Christianity will help you and how good it is for society, have actually led you to forget that Christianity is not a patent medicine. Christianity claims to give an account of facts — to tell you what the real universe is like. Its account of the universe may be true, or it may not, and once the question is really before you, then your natural inquisitiveness must make you want to know the answer. If Christianity is untrue, then no honest man will want to believe it, however helpful it might be: if it is true, every honest man will want to believe it, even if it gives him no help at all.”

To believe for instrumental reasons is to be a rabbit, not a man. Most atheists quite like this line by CS Lewis: he makes the stakes of theology and metaphysics clear. You either want to know what’s true or not–and the idea of instrumentalizing our beliefs for community or health or the cultivation of virtue or comfort is a deep transgression of our natures. Only a scared little bunny-rabbit would make such a mistake, and deserve our disdain for it.

It’s Lewis who is deeply wrong, though. Wanting the truth no matter what the consequences is almost impossible for most humans to achieve. Wanting the truth when it comes to matters of identity and community is bad for survival, and a lot of our the things we espouse are designed to signal to others that loyalty matters more than accuracy. We’ve discovered that a large portion of our cognitive capacity is devoted to monitoring our friends and neighbors and setting our beliefs in line with their expectations: motivated reasoning and skepticism help us engage in identity-protective cognition in all sorts of cases.

What then does an ethics of belief look like? I think it’s tempting to say that we should pursue the old ideals with this new knowledge: aim to cut ourselves off from the epistemic judgments of friends and neighbors, aim to hold every identity lightly enough that we can jettison it rather than protect it when the evidence turns against us. But for a variety of reasons I doubt that anyone–least of all professional skeptics and philosophers–can do that all the time or on a regular basis, let alone about the matters that will end up being most important.

For one thing, the only thing worse than epistemic in-groups is to be an epistemic exile: one important reason we need to participate in cultural cognition is because the patterns of epistemic deference and trust they engender helps us manage the firehose of possible sources of information. We need trust to know–even if we’ll also be misled into error by that trust.

Put another way, heuristics are not biases, because we can’t see the truth at all without some semi-reliable method. But this keeps the question of an ethics of belief alive, it doesn’t settle anything. There are still key moments when we ought to betray our identities in the search for the truth–but when? And just as importantly–how? And how will we know?

(related: Warning Signs: Beliefs that Signal Loyalty or Ability, Snark Polemics and Contrite Fallibilism, Reason & Rallying)

Undivided Nation Bridging Divides One State at a Time

Have you been keeping up with the travels of NCDD member Undivided Nation? David and Erin Leaverton and their family are traveling to every state in the US in order to listen to peoples’ stories and bring folks together over dinner to dialogue with “the other”; all to explore the myriad of experiences in our country and to find our connection points despite differences. They have shared with us a powerful learning opportunity they experienced in their journey about the way divisions manifest in peoples’ lives and emphasized the need to address the oppressive realities that exist only for certain groups of people.

On their journey, they would like to develop a film, Know Thy Other, to share their experiences of this important work of listening and bridging divides The film will document their travels and powerful conversations; in hopes of better understanding what divides us and address the bigotry that comes from not recognizing the humanity of “the other”. Help amplify the impact of their work by donating to the film’s Kickstarter! You can read the post below and we encourage you to donate to their tax-deductible Kickstarter here.

It’s Hard to Reconcile with Someone Who Has a Boot on Your Neck

By David Leaverton

The 2016 Presidential election was a turning point in my life. Before my eyes, I saw many of my fellow countrymen treat each other not as political opponents, but as mortal enemies. Fear and division had gripped this land and I couldn’t sit on the sidelines any longer.

The 2016 Presidential election was a turning point in my life. Before my eyes, I saw many of my fellow countrymen treat each other not as political opponents, but as mortal enemies. Fear and division had gripped this land and I couldn’t sit on the sidelines any longer.

As a newcomer to the NCDD community, I had a desire to help bridge these divides and see our nation united, but I knew I first needed to gain a deeper understanding of the problem before I could offer up any real solutions to the discussion.

To find the answers we were looking for, my wife and I sold our house, quit our jobs and set out on a 50-state road trip with our three kids. As I write this, I am looking out from our RV over the spectacular Greenbrier River in West Virginia, state number 12 on our journey. To say we have been transformed by this experience so far would be an understatement.

As we enter each new state, we often go into a community knowing no one and cold calling or emailing leaders and organizations who represent different groups within in the community. I was recently on the phone with a leading African-American individual in Savannah, GA, sharing our journey and our mission for reconciliation and unity in America.

As I shared the purpose of our trip, which is often met with interest or curiosity, this gentleman sounded almost offended at my goal to seek reconciliation and common ground. While he was neither hateful nor rude, he still gave it to me straight when he said, “It’s hard to reconcile with someone who has a boot on your neck.”

That one line changed me.

One thing I have come to realize on our journey is that there are a number of Americans who wake up every day with a feeling of oppression in an America that I didn’t know existed. This was so disappointing to me as a proud patriot who believes in the America where all men are touted as being equal and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights.

Thinking of this situation in literal terms, it is woefully insensitive for me to walk up to the individual on the ground with the boot on their neck to talk about forgiveness and reconciliation without first addressing the boot, and doing everything in my power to remove it.

I was never able to meet with this gentleman, but what I gained through his refusal to meet with me was probably more valuable.

I learned some important lessons about reconciliation from this brief but poignant conversation.

When we hope for reconciliation between two parties, we must first address and try to eliminate the cause of oppression or pain being experienced either party before the discussion can get too far. No one knows the boot better than the one whose neck it is on and they must be part of the process of understanding the situation. We may not have the ability to quickly remove the boot, but we can begin by acknowledging and addressing the situation as best we can.

I began this journey focused on our political divisions, but haven’t been able to get away from the racial divisions in our nation as I’ve begun to explore it. Many of the people we have spoken with, and this is by no means a scientific representative sample of the country, have been impacted more by our racial divides than the infighting in Congress.

Our history of oppression of Americans with deeper pigmentation in this country is extensive. Our journey across the country so far has taught us that slavery in America didn’t end with the Emancipation Proclamation or the Civil War. Oppression has continued under different names such as convict leasing, sharecropping, peonage, lynching, segregation, Jim Crow, redlining, mass incarceration, among others. Although the current situation in our nation regarding racial and ethnic disparities is extremely complex beyond skin pigmentation, learning these truths about our history has been vital in our quest for reconciliation and unity.

While I still have more questions than answers on the subject of division in our country, I do know that at the end of our year-long journey, I can’t go back to being a silent bystander.

David Leaverton and his wife, Erin, are the founders of Undivided Nation, an organization focused on serving as a catalyst for reconciliation and unity in America. They live with their three children on an RV somewhere in America. Follow their journey at http://undividednation.us.

agenda for Frontiers of Democracy 2018 is taking shape

There is still room to register and pay to hold a spot for Frontiers of Democracy 2018 (June 21-23 in Boston). Although many slots on the agenda are filled, there is still room for a few more proposals for sessions or presentations. The following is an incomplete list of the confirmed speakers and sessions, with several more in the pipeline for approval.

Keynotes

“Innovating Democracy Reform”

Josh Silver, Founder & Executive Director, Represent.us

“Activism under Fire: Violence, Poverty and Collective Action in Rio de Janeiro”

Anjuli Fahlberg, Northeastern University

“Fear and Present Danger”

Kelly Greenhill, Tufts University

“The Disenfranchised”

Sekwan R. Merritt, a formerly incarcerated person who advocates for an end to mass incarceration in America

“Overcoming Civic Fragmentation Through Public Work”

Harry Boyte, Augsburg College

“These Words: A Century of Printing, Writing, and Reading in Boston’s Chinese Community”

Susan Chinsen, Managing Director, The Chinese Historical Society of New England

Presentations and Sessions

(The category headings are for information only. Some titles refer to standalone sessions, while others will be combined to create panels. The panels may not be organized along these topical lines.)

Institutions in Communities

“How Can Museums Strengthen a Civil Society?”

Abby Pfisterer, Education Specialist; Magdalena Mieri, National Museum of American History; Rebekah Hardingrharding, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library; Michelle Martz, Lincoln Cottage; Teresita Paniagua, La Casita; Noelle Trent, National Civil Rights Museum; Dory Lerner, National Civil Rights Museum; Abby Kiesa, Director of Impact, CIRCLE, Tisch College

“The Role of Religious Communities in Strengthening Democracy”

Elizabeth Gish, Western Kentucky University, and John Dedrick, Kettering Foundation

“Civic Tinkering as Democratic Practice”

Scott Tate, Virginia Tech

Youth Voice

“The 2016 Boston Student Walkout Movement: Stories, Strategies, and Impacts”

Andrew King, Mark Warren, Mariette Ayala, Sheetal Gowda, Kate Kelly, Jeff Moyer, and Luis Navarro

“Unchaining the Power of Student Voices”

Frank LoMonte, The Brechner Center, and Zack Mezera, Providence Student Union

“Building Agency and Voice in Student Activists”

Pamela Conners and Leila Brammer, Gustavus Adolphus College

Media and Tech

“Data Justice: A Hands-On Workshop”

Libby Falck, MIT

“Civic Entertainment”

Anushka Shah, MIT Media Lab

“Votes that Count and Voters Who Don’t: How Journalists Sideline Electoral Participation”

Sharon Jarvis, University of Texas at Austin and Annette Strauss Institute for Civic Life

“If Only Journalists Care about the Future of Journalism, Democracy is in Trouble”

Fiona Morgan, Free Press

“What are the Responsibilities of Civic Technology?”

Erhardt Graeff, MIT Media Lab

“Bridging the US Political Divide Online: What we Learned from Using Big Data”

Kate Mytty, Build Up

Education (K12 and College)

“Civic Learning and Young Citizens: Democratic Engagements in Higher Education “

Ivy Dhar, School of Development Studies, Ambedkar University Delhi (AUD), and Nidhi S. Sabharwal, Centre for Policy Research in Higher Education (CPRHE), National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration (NIEPA), India

“Deliberative Dialogue in Classrooms and Other Settings”

Sharyn Lowenstein and Denny Frey, Lasell College

Connecting the Public and Government

“The Missing Link: Connecting Our Work to The People Who Need It”

Larry Schooler, National Civic League

“State of the Congress: Staff Perspectives on Congressional Capacity”

Kathy Goldschmidt, Congressional Management Foundation

Getting Past Division

“How can we productively talk about divisiveness in a time of polarized public discourse?”

Elizabeth Gish, Western Kentucky University, and John Dedrick, Kettering Foundation

“Civility In Our Democracy – Collaborating and Rebuilding Bridges of Trust, and Respect”

Cheryl Graeve and Ted Celeste, National Institute for Civil Discourse

State-Wide Strategies

“Democracy in your backyard: Building local and state capacity for participatory public engagement”

Quixada Moore-Vissing, Michele Holt-Shannon, and Bruce Mallory, New Hampshire Listens

“Civic Health in a Changing Landscape: Arizona as a Case Study”

Kristi Tate, Center for the Future of Arizona

Searching for Balance: America’s Role in the World (Connections 2016)

The seven-page article, “Searching for Balance: America’s Role in the World” by Robert J. Kingston was published in Kettering Foundation‘s 2016 edition of their annual newsletter, Connections – Kettering’s Multinational Research. For the eleventh article of the newsletter, Kettering drew from Kingston’s book Voice and Judgment: The Practice of Public Politics which discusses the role America should engage in when interacting with international relations. Below is an excerpt from the article and Connections 2016 is available for free PDF download on Kettering’s site here.

From the article…

All of us, I suspect, while we were still young children, encountered some history-making event that we know was to change the comfort of our little world. We did not surely understand it, nor even really “know” what it was; but we knew that it “happened,” that it “meant” something, and that someday, therefore, we should have to cope with it. To the now elders among American citizens, such an “event” may have been Pearl Harbor or the atomic bomb on Hiroshima; to a very few, even Poland, or Neville Chamberlain getting off a plane from Munich, a piece of paper (signed by Adolf Hitler) fluttering in his hand declaring, more wrongly than he could imagine, “Peace in our time!” Or for a somewhat younger generation, it will have been 9/11—and new enemies, new friends.

The long and continuing sequence of National Issues Forums—which (as this is being written) have addressed something near 100 issues, nationwide, over the past 30 years— provides now a valuable indication of the progress of public thinking, and the continuities in it, over time, otherwise unavailable, the likelihood of which was perhaps not fully apprehended during the earliest years of the NIF experiment. America’s sense of its place in the world is one such continuing theme.

In the 1980s the country passed through the depths of the Cold War, which, in effect, culminated with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Well, this was perhaps not the precise “depth” of the Cold War, granted Sputnik, the space race, and the Cuban Missile Crisis; but the period was certainly filled with deeply troubled and passionate concern about the relative nuclear strengths of the two superpower rivals. Three times in that decade the NIF forums took on a consideration of the US-Soviet relationship. Then again, immediately following the end of the Soviet era in 1989, they turned to consideration of America’s role in the world. And in the fall and winter of 2002-2003, within weeks of the US attack on Iraq, citizens were again discussing “Americans’ Role in the World” in their National Issues Forums.

Questions of international relations and foreign policy present a particular challenge to citizens of democracies, especially if they see themselves as a nation of immigrants. For most of the past century, fortunate Americans thought of themselves as somewhat better off than the rest of the world, and perhaps envied by it! When wars have had to be fought, they have been fought in places other than the United States itself and caused less of its citizenry to be directly involved in fighting. And the outcomes of the Second World War and the Cold War seemed to place the United States in a position where it could provide extraordinary assistance to the rest of the world, while fearing virtually nothing from it. At least, so some leaders and many citizens like to presume, while others seemed sometimes to prefer to pursue a policy of strength through fear.

This is just an excerpt, you can read the rest of the article by clicking here.

About Kettering Foundation and Connections

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

Each issue of this annual newsletter focuses on a particular area of Kettering’s research. The 2016 issue of Connections, edited by KF program officer and senior writer/editor Melinda Gilmore; KF senior associate Philip Stewart; and KF vice president, secretary, and general counsel Maxine Thomas, focuses on our year-long review of our multinational research.

Follow on Twitter: @KetteringFdn

Resource Link: www.kettering.org/sites/default/files/periodical-article/Kingston-Connections-2016.pdf

MetroQuest Webinar on TxDOT Innovative Engagement

Next week, NCDD member org MetroQuest will be hosting the webinar, Public Involvement – How TxDOT Engages Beyond Meetings; co-sponsored by NCDD, IAP2, and the American Planning Association (APA). The webinar on Tuesday, April 17th will feature speakers from the Texas Dept of Transportation on their innovative outreach approaches and how online engagement input is informing transportation decisions in Texas. You can read the announcement below or find the original on MetroQuest’s site here.

MetroQuest Webinar: Public Involvement – How TxDOT Engages Beyond Meetings

Join TxDOT as we explore how the agency extends its public involvement mission via interactive engagement.

Join TxDOT as we explore how the agency extends its public involvement mission via interactive engagement.

Tuesday, April 17th

11 am Pacific | 12 pm Mountain | 1 pm Central | 2 pm Eastern (1 hour)

Educational Credit Available (APA AICP CM)

Complimentary (FREE)

Getting meaningful public involvement on transportation projects is challenging. The public are not planners … yet they care about local congestion, mobility, and safety. Learn how TxDOT embraces innovation to successfully educate and engage residents on projects at any scale.

Join Jefferson Grimes, Director of Public Involvement, with Amy Redmond and Julie Jerome from TxDOT as they share innovative approaches to reaching an exceedingly busy and diverse public to collect meaningful input on transportation projects. From broader, long-term corridor studies to smaller, more specific projects, input from online engagement is informing transportation decisions in Texas. This team will share strategies and techniques that encourage participation and provides meaningful data in project planning.

Register for this complimentary 1-hour live webinar to learn how to …

- Educate the public about the planning process

- Collect informed input to help in decision making

- Gather input beyond public meetings

- Engage diverse populations

- Seating is limited – save your spot today!

Speakers

Jefferson Grimes – Director of Public Involvement, Texas Department of Transportation

Jefferson and his staff serve as the central focus point in ensuring that agency public involvement efforts are meaningful and results-oriented. He is charged with establishing agency policies and procedures governing outreach and the involvement of the public in agency decisions on projects. Jefferson has been solving transportation issues for TxDOT for nearly 30 years in a variety of capacities.

Julie Jerome – Public Involvement Specialist, Texas Department of Transportation

Julie Jerome is one of a team of four supporting and guiding public involvement efforts for transportation projects all over Texas. The team works closely with TxDOT’s 25 districts to ensure effective public involvement strategies and techniques throughout the life of a project—from planning to construction to maintenance—for more than 80,000 miles of road, plus aviation, rail and public transportation.

Amy Redmond – Public Involvement Specialist, Texas Department of Transportation

Amy has civic engagement engraved in her DNA. Her passion for public service has taken her to every corner of the Lone Star State working on projects for TxDOT, Texas Public Broadcasting, the Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts and Texas State University. Working 18 years in public, nonprofit and private entities she employs a diversity of knowledge to output ideas so that the world will understand.

You can find the original version of this announcement on MetroQuest’s site at http://go.metroquest.com/Public-Involvement-with-TxDOT.html