As our technology continues to flourish and many use it as a major tool for engaging communities, how do we make sure that engagement processes and practices are accessible to those who have limited literacy skills? NCDDer Bang the Table recently shared an article on best practices for engaging with communities online that have low-literacy that we encourage you to read. You can read the article below and find the original on Bang the Table’s site here.

4 key ways to engage with low-literacy communities online

Most online engagement involves text and interactive tools that require, or assume, an ability to write and express opinions. But where does that leave community members who have low levels of literacy?

Most online engagement involves text and interactive tools that require, or assume, an ability to write and express opinions. But where does that leave community members who have low levels of literacy?

People with limited literacy levels represent a significant percentage of the community. In Australia, while around 14 per cent of adults – just over 1 in 7 – have limited literacy skills, 1 in 5, or around44 percent of people, lack literary skills required for everyday life. Alternately, 42 percent of Canadian adults have low literacy skills while, in the USA, some 36 million adults cannot read, write or perform basic maths, which has remained largely unchanged in over ten years. In the UK, 1 in 7 adults in England lack basic literacy skills, while nearly 30 per cent of the workforce in Ireland hold the equivalent of a junior certificate, with 10 per cent only primary level or no formal qualifications at all. Indeed, The Programme for International Assessment for Adult Compentencies (PIACC) Survey of Adult Skills reveals that a considerable number of adults in 40 OECD countries possess only limited literacy and numeracy skills.

Most adults with literacy difficulties can read something but find it hard to understand complex, detailed forms or deal with digital technology. As a result, some are hesitant, or less likely to use technology. For some, barriers may exist around using verbal and non-verbal communications. TheUK’s literacy trust write: “People with low literacy skills may not be able to read a book or newspaper, understand road signs or price labels, make sense of a bus or train timetable, fill out a form, read instructions on medicines or use the internet.”

Difficulties reading, writing, working with numbers and self-expression not only contributes to societal exclusion but is an all-pervasive issue when working in the space of community engagement. Core to the values of community engagement is the ability to ensure that everyone has a say on issues that impact their everyday lives. But, on the flipside, low literacy is often hidden or masked.

Low literacy levels are frequently well camouflaged, making it not only hard to identify, but also hard to reach. This can include: linguistically diverse groups (migrant communities, for instance, have complex literacy profiles); people not wanting to identify as “disabled”; and people with psychological and cognitive disabilities, such as dyslexia – itself referred to as an “invisible disability” (it is estimated to affect 10 to 15 per cent of the population).

These are added to by the “intergenerational cycle”, or family literacy where people who grow up in a family with low literacy, themselves often develop have limited literacy skills. According the UK’s Literacy Trust, this “makes social mobility and a fairer society more difficult”. These “invisible” measures not only make figures of low literacy potentially much higher, but, more importantly, limiting the capacity for civic participation, make engaging with low literacy communities essential.

Without systematic consideration of low literacy communities, it would seem that in efforts to engage people in decisions that affect their everyday lives – to provide equal access for all to ensure everyone has their say – a context for failure and exclusion will be created. Indeed, community members with lower general verbal ability and difficulty with phonetic processing would struggle with most traditional methods of engagement. How would they respond to a survey for instance, or qualitatively rate issues without means to express themselves? How, then, should accessibility in engagement with low-literacy communities work?

While face-to-face engagement can involve advocacy groups, engage people of trust to those with low literacy skills and provide opportunities for support (for example, using signing or braille), there appears little analysis of pragmatic and practical ways to engage low literacy communities online – particularly, in an increasingly digitally-focussed world. How can we translate this inclusive engagement online?

On the other hand, holding online engagement up to the same prism can overlook its unique potential. Online accessibility can suggest real optimism: it emphasises beneficial ways technology and design potentially transform the lives of people with diverse physical, cognitive and sensory abilities and needs. Perhaps the question is, then, what are the opportunities open to online engagement with low literacy communities?

Here are 4 key ways to engage low-literacy communities online:

1. PLAIN TEXT: USE WRITTEN INFORMATION ACCESSIBLY

- Use everyday language and, where possible, images to assist with meaning.

- Avoid jargon.

- Be mindful of the nuances of language.

This is particularly salient with “invisible” low literacy communities as not all people use the same terminology – some may not self-identify as experiencing low levels literacy. In addition, diverse groups have differing needs, for example, people with autism would commonly have difficult understanding figures of speech, “raining cats and dogs”.

- Use inclusive language: avoid labels, generic terms and emotive language.

Inappropriate language can result in feeling excluded, for instance, describing that people “suffer” or are “afflicted with” low literacy. Equally, in the search for equality, it is important not to use language that can be perceived as condescending, for instance, describing low literacy communities as “inspirational” or “brave” etc.

- Consider written materials in engagement methods and feedback.

Will there be newsletters? How will you publish survey results? How will provide feedback? True inclusivity means that everyone’s views help inform decision-making.

Is the information as clear, simple and concise as possible?

Use standard capital and lowercase sentences, especially in headings; use bold for emphasis rather than italics, which are harder to read, and underscore hyperlinks. Many PDF files are incompatible with screen reader software packages, so consider publishing word or HTML versions alongside PDFs.

- Create easy read versions/translations of all text documents.

NB: In order to access information and engage on the same basis as other people, low level literacy communities may require differing formats. For example, Microsoft Word document’s can be read aloud using a screen reader.

2. VIDEO AND AUDIO

- Use short engaging videos.

Video imaging can convey key messages on issues or create imaginative calls to action to get involved in an engagement process.

- Use conversational audio and video

Consider audience literacy, perhaps through conducting conversations/audio, such as podcasts, at a slightly slower pace.

- Use audible versions of all video and audio files.

3. INFOGRAPHICS AND IMAGES

- Use images, diagrams and graphs to make information more accessible.

- Use brief written descriptions to accompany images.

- Use data visualisation instead of tables.

Tables are notoriously incompatible with screen reader software used by blind people or those with vision impairments. They are also difficult to reproduce in large print.

- Don’t use text over graphics, patterns or blocks of colour or dark shading

- Use colour to visually communicate qualitative aspects of issues – ie viewers can form colour analogies to indicate emotive expression (i.e. danger = red).

4. DIGITAL STORYTELLING

Anecdotally, low literacy people rely on their friends and family (with higher literacy levels) to share information with them, often via conversation and talking. Digital storytelling is a simple, creative way where people with little to no online experience can tell a personal story. It provides a means of self-expression and opens up a self-identified way to become involved in engagement issues, provides a respect for the diversity of participants and ensures their voices are heard.

- Provide a capacity for low literacy people to narrate stories online.

This provides access to self-identifying and an agency for their engagement. While participant testimonials are often essential at feedback stage, they exclude participation by people with low literacy skills. Storytelling provides a great way of capturing the voice of your participants and facilitates a way to demonstrate their views inform decision-making.

- Draw on different digital formats.

Through the use of photos, online drawings and digital media, a personal or strong emotional connection can be built into the engagement process and centres the experience on the participant. Ensuring a personal connection, this recognises low literacy participants as experts in their own lives and experiences.

You can find the original version of this article on Bang the Table’s site at www.bangthetable.com/4-key-ways-engage-low-literacy-communities-online/.

![]() Description: What exactly is engagement and why does it matter? How do you make the case that your organization or community should be engaging more? Why are residents expecting (or demanding) different opportunities to engage? What are “thick” and “thin” forms of engagement? How can engagement affect political and social inequities? What are the cutting-edge trends and tools, and the latest success stories? What are the mistakes to avoid?

Description: What exactly is engagement and why does it matter? How do you make the case that your organization or community should be engaging more? Why are residents expecting (or demanding) different opportunities to engage? What are “thick” and “thin” forms of engagement? How can engagement affect political and social inequities? What are the cutting-edge trends and tools, and the latest success stories? What are the mistakes to avoid?

Most online engagement involves text and interactive tools that require, or assume, an ability to write and express opinions. But where does that leave community members who have low levels of literacy?

Most online engagement involves text and interactive tools that require, or assume, an ability to write and express opinions. But where does that leave community members who have low levels of literacy?

Last month, veteran National Issues Forums (NIF) convener and moderator, Gregg Kaufman

Last month, veteran National Issues Forums (NIF) convener and moderator, Gregg Kaufman

Podcast:

Podcast:

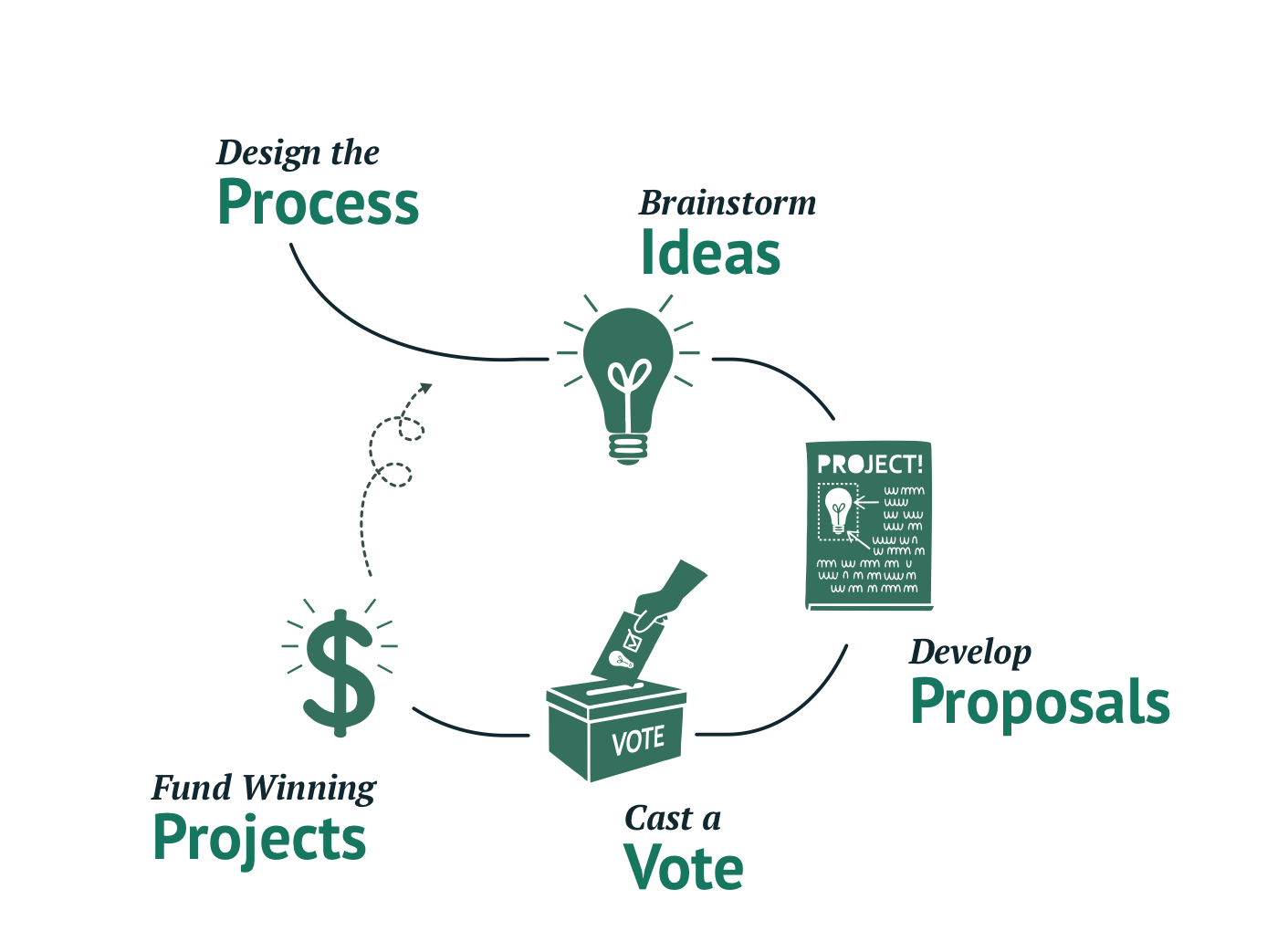

To create truly inclusive PB processes, low-income residents and people of color must be well represented on the steering committee and as budget delegates. The steering committee sets the rules for a PB process, and these rules ensure an inclusive and fair process. When low-income people and people of color are not in the room, steering committees miss valuable ideas on how to create a fair process.

To create truly inclusive PB processes, low-income residents and people of color must be well represented on the steering committee and as budget delegates. The steering committee sets the rules for a PB process, and these rules ensure an inclusive and fair process. When low-income people and people of color are not in the room, steering committees miss valuable ideas on how to create a fair process.

Government representatives should make themselves open and available to their community. Simple changes in tone and body language can mean the difference between intimidating residents and engaging them.

Government representatives should make themselves open and available to their community. Simple changes in tone and body language can mean the difference between intimidating residents and engaging them. Some residents told Celina that they would not have voted for surveillance cameras had they known that the community would not have had control over the footage. It’s critical that PB participants understand the ramifications of what they are voting for so that they can make an informed decision.

Some residents told Celina that they would not have voted for surveillance cameras had they known that the community would not have had control over the footage. It’s critical that PB participants understand the ramifications of what they are voting for so that they can make an informed decision.