Monthly Archives: August 2016

white working class alienation from government

In a recent long post, I argued that one reason white working class Americans are alienated from government is that they lack the productive political power that comes from organizations, such as political parties that rely on ordinary members, and unions. Moreover, because of the weakness of such organizations, white working class people are simply not visible in positions of power. A few leaders can rightly say that they started life in the working class, but almost by definition, they are now all well-paid and highly educated professionals.

recent long post, I argued that one reason white working class Americans are alienated from government is that they lack the productive political power that comes from organizations, such as political parties that rely on ordinary members, and unions. Moreover, because of the weakness of such organizations, white working class people are simply not visible in positions of power. A few leaders can rightly say that they started life in the working class, but almost by definition, they are now all well-paid and highly educated professionals.

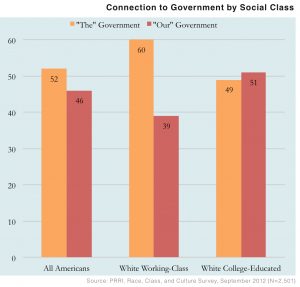

As a supportive data point, here is a graph from a 2012 PRRI survey. Respondents are asked: “When you think and talk about government, do you tend to think of it more as ‘the government’ or more as ‘our government?'” The adult population is fairly evenly split, with almost half of Americans opting for “our government.” More than half of white college-educated people see things that way. But six-in-ten working class whites perceive it as “the government.” Among seniors who are working-class whites, a majority still see it as “their” government. That could be because they are invested in certain government policies (such as Social Security and Medicare), but it’s also true that they came of age at a time when working-class people exercised political power. Among young working-class whites, 70% see it as “the government.”

I don’t think they’re wrong. It is “the” government rather than “their” government in a meaningful sense. But as long as they feel this way, and no one offers actual empowerment, they are going to be ripe targets for demagogues who want to blow the whole thing up.

The Self and the Great Community

John Dewey saw democracy as an ideal expression of associated living.

That’s a bit of an understatement though, because for Dewey, democracy is much more than “a special political form, a method of conducting government, of making laws and carrying on governmental administration.” Such institutions are an element of democracy, but fundamentally, Dewey argued, democracy is a way of life.

To Dewey, democracy is recognizing “the necessity for the participation of every mature human being in formation of the values that regulate the living of men together: which is necessary from the standpoint of both the general social welfare and the full development of human beings as individuals.”

This concept of democracy is deeply tied to Dewey’s understanding of humanity. Indeed, Dewey argued, democracy is the process through which people learn to be human – and being human is the process through which people exercise democracy. As he eloquently described in The Public and its Problems:

To learn to be human is to develop through the give-and-take of communication an effective sense of being an individually distinctive member of a community; one who understands and appreciates its beliefs, desires and methods, and who contributes to a further conversion of organic powers into human resources and values.

I’m particularly struck here by Dewey’s vision of the democratic citizen as one who perceives themselves as an “individually distinctive member of a community.” Dewey clearly embraces the idea of “I” as unique and self-aware being, and yet there’s something in his language which nods to a broader understanding of “self.”

He goes on to talk about the illusion of a false psychology:

…Current philosophy held that ideas and knowledge were functions of a mind or consciousness which originated in individuals by means of isolated contact with objects. But in fact, knowledge is a function of association and communication; it depends upon tradition, upon tools and methods socially transmitted, developed and sanctioned.

Associated living, Dewey argued, is “physical and organic,” but communal life – embracing the “self” not strictly as an isolated being, but as a being created by and reflective of its many associations – is moral: it is “emotionally, intellectually, consciously sustained.”

We differentiate humanity from animals by celebrating our consciousness, by claiming that we alone have the capacity to recognize that there is an “I” and by embracing self-awareness as a distinctively human trait.

Perhaps this is not far enough.

Not only is it unlikely that self-awareness is a uniquely human capacity, but it fails to capture humanity’s true gift. Dewey writes, “For beings whose ideas are absorbed by impulses and become sentiments and interests, ‘we’ is as inevitable as ‘I’.”

In short, “self” is not the unit we should be thinking in. There is a self, Dewey seems to argue; there is something about ‘me’ which is uniquely distinctive from ‘you’. But my self and your self are not as unique an independent as we might imagine. We are intricately tied up, interconnected, and interdependent. I cannot exist without you. I make you and you make me.

We are each of us, indelibly, co-created.

Recognizing and embracing that interdependence is what makes Dewey’s Great Community possible. Our biology ensures that we are associated beings – a baby, after all, cannot survive on its own. But through conscious and intellectual decisions, by recognizing that it is not only our fates but our very beings which are intertwined, we make communities.

We are far from achieving this yet – certainly terribly far from it on a global scale. As Dewey writes, “the old Adam, the unregenerate element in human nature, persist. It shows itself wherever the method obtains of attaining results by use of force instead of by the method of communication and enlightenment. It manifests itself more subtly, pervasively and effectually when knowledge and the instrumentalities of skill which are the product of communal life are employed in the service of wants and impulses which have not themselves been modified by reference to a shared interest.”

Yes, the old Adam persists. We hang doggedly to the idea that I have made my own way and that there is an isolated ‘I’ which has a way to make. We forget that we are fundamentally associated beings, and we underestimate the pockets of community collectively built. The old Adam persists, but a new vision is slowly taking its place; an awaking to ourselves as individually distinctive member of a community. Distinctive, perhaps, but inextricably intertwined.

Join Our Aug. Confab Call on Building an Online Commons!

You’re invited to join us for our next NCDD Confab Call on Thursday, August 25th from 1-2 PM Eastern (10am-12pm Pacific)! This interactive conference call will feature John Gastil, a democracy scholar and long-time NCDD member, and Luke Hohmann, CEO of Conteneo, Inc., who will share about a ground-breaking civic tech idea that they are working together to make into a reality. Register today to save your spot!

John and Luke are gathering together software designers, civic reformers, academics, and public officials to envision and build an integrated online commons – a commons that would link together the best existing civic tech and other online deliberation and engagement tools by making them components in a larger “Democracy Machine.”

The purpose of the call is to discuss ideas about the design and development of the machine in advance of a session on the same topic during NCDD 2016 this October. The aim is to draw new people into the civic sphere, encourage more sustained and deliberative engagement, and send ongoing feedback to both government and citizens to improve how the public interfaces with the public sector. In advance of the call, we encourage participants to read about the basic concept in John’s recent post on the Challenges to Democracy blog or read his full essay, “Building a Democracy Machine: Toward an Integrated and Empowered Form of Democracy,” by clicking here

John Gastil is a professor in the Department of Communication Arts and Sciences at the Pennsylvania State University. His research focuses on the theory and practice of deliberative democracy, particularly as it relates to how people make decisions in small groups on matters of public concern. His recent books include The Jury and Democracy, The Group in Society, and Democracy in Small Groups: Participation, Decision Making, and Communication (2nd ed.).

Luke Hohmann is CEO of Conteneo, Inc. Conteneo is the leading provider of collaboration – not communication – solutions for the public and private sector. Through their cutting-edge technology and customized services, Conteneo enables employees, customers, and partners to work better together – no matter where they are in the world. Thousands of business leaders are using the Conteneo Collaboration Cloud and our Collaboration Consulting services to be more productive, innovative and competitive.

NCDD’s interactive Confab Calls are free and open to all members and potential members. Register today if you’d like to join us!

About NCDD’s Confab Calls…

NCDD’s Confab Calls are opportunities for members (and potential members) of NCDD to talk with and hear from innovators in our field about the work they’re doing, and to connect with fellow members around shared interests. Membership in NCDD is encouraged but not required for participation. Register today if you’d like to join us.

NCDD’s Confab Calls are opportunities for members (and potential members) of NCDD to talk with and hear from innovators in our field about the work they’re doing, and to connect with fellow members around shared interests. Membership in NCDD is encouraged but not required for participation. Register today if you’d like to join us.

Multi-criteria Decision Analysis

Method: Multi-criteria Decision Analysis

Scarborough Beach Deliberative Survey

against root cause analysis

I am skeptical of the idea of “root causes” and the assumption that progress comes from addressing the roots of problems. The following points draw from discussions in our annual Summer Institutes of Civic Studies and are indebted to my co-teacher, Karol Soltan.

- The metaphor of a “root” seems misplaced. Social issues are not like plants that have one root system at the bottom and branches and leaves at the top, so that if you cut or move the root, you kill or move the whole plant with a single action. Very often, social phenomena are connected in systems that incorporate feedback loops and cycles, whether virtuous or vicious. It’s possible for one thing (A) to affect another thing (B) and for B also to affect A. Very often, outcomes are not the result of one ultimate cause but of the interaction of many causes. And causes can be viewed as outcomes, because there’s lots of reciprocal causation.

- Often, successful social action occurs even though the activists don’t know the root cause of a problem or they disagree about what it is. An example is the global movement to end slavery. Religious abolitionists argued that the root cause of slavery was sin, going back to the Fall of Man. “Free labor” abolitionists, like Abraham Lincoln, said that slavery was a plot to undermine a competitive market of labor in which the individual worker could profit. In contrast, Karl Marx wrote in 1847 that slavery was a lynchpin of global capitalism: “Direct slavery is just as much the pivot of bourgeois industry as machinery, credits, etc. Without slavery you have no cotton; without cotton you have no modern industry. It is slavery that has given the colonies their value; it is the colonies that have created world trade, and it is world trade that is the pre-condition of large-scale industry.” Frederick Douglass saw racism (“the wolfish hate and snobbish pride of race”) as a–or perhaps the–root cause of slavery. I suppose that all of them pointed to genuine causal factors, but the main point is that they formed a coalition that targeted the actual problem, not its underlying causes, and they won.

- Trying to identify root causes can delay or even block effective action. My friends Joel Westheimer and Joe Kahne wrote a very influential and valuable paper in 2004 entitled “Educating the ‘Good’ Citizen: Political Choices and Pedagogical Goals.”* They found that civic education programs in the US tended to fall into three categories, defined by their objectives for the students. An example illustrates the differences. In a program that aims to produce “personally responsible citizens,” a student will “contribute food to a food drive.” In a program whose ideal is to develop “participatory citizens,” a student will “help to organize a food drive.” In a program that emphasizes “justice-oriented citizens,” the student will “explore why people are hungry and act to solve root causes.” As Karol notes, the first two begin with an action, but the third begins with “exploring,” which doesn’t actually do any good in the world. Now, to be sure, one can also explore a diagram of a complex, interconnected system for a long time before doing anything, so it’s not only root-cause analysis that can fatally delay action. But I think that root-cause analysis is particularly likely to frustrate action because it sends us in search of the biggest, hardest, deepest aspect of a problem, which is exactly where the odds of success may be lowest. And that’s a mistake if problems do not actually have roots.

*Political Science and Politics, April 2004, pp 241-24.

See also Roberto Unger against root causes and roots of crime.

Participatory Reflection and Action

NHPRC Offers Grants Available for Engagement with Historical Records

We recently heard about an interesting opportunity from our friends with the American Library Association’s Center for Civic Life, and we wanted to make sure our members heard about it. The Center recently shared an announcement about a grant opportunity for efforts that use historical records to spark public engagement, and we encourage our members to consider applying. Learn more in the ALA’s announcement below or find the original version here.

Public Engagement with Historical Records Grants through the NHPRC

Public Engagement with Historical Records

The National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) of the National Archives supports projects that promote access to America’s historical records to encourage understanding of our democracy, history, and culture.

The following grant application information is for Public Engagement with Historical Records.

Funding Opportunity Number: ENGAGEMENT-201610

Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance (CFDA) Number: 89.003

Draft Deadline (optional): July 26, 2016

Final Deadline: October 6, 2016

NHPRC support begins no earlier than July 1, 2017.

Grant Program Description

The National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) seeks projects that encourage public engagement with historical records, including the development of new tools that enable people to engage online. The NHPRC is looking for projects that create models and technologies that other institutions can freely adopt. In general, collaborations among archivists, documentary editors, historians, educators, and/or community-based individuals are more likely to create a competitive proposal.

Projects might create and develop programs to engage people in the study and use of historical records for institutional, educational or personal reasons. For example, an applicant can:

- Enlist volunteer “citizen archivists” in projects to accelerate access to historical records, especially those online. This may include, but is not limited to, efforts to identify, tag, transcribe, annotate, or otherwise enhance digitized historical records.

- Develop educational programs for K-16 students or community members that encourage them to engage with historical records already in repositories or that are collected as part of the project.

You can find the original version of this post from the American Libraries Association at http://discuss.ala.org/civicengagement/2016/07/23/public-engagement-with-historical-records-grants-through-the-nhprc.