Monthly Archives: August 2016

Freedom, Choice, and Civic Life

I’ve been reading Sarah Bakewell’s delightful At the Existentialist Café, something of an existentialist study of the existentialist movement. The book follows the life, times, and beliefs of some of the 20th century’s most prominent existentialists, the German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl, his protégé Martin Heidegger, and continuing through the great French philosophers Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

Along the way we meet many of their friends and colleagues – notable philosophers in their own right – whose lives are integral to Bakewell’s study but whose stories are not the focus of this particular work: Edith Stein, Emmanuel Levinas, Karl Jaspers, Hannah Arendt, Raymond Aron, Arthur Koestler, and many others.

I’m familiar with the famous works of these philosophers, but beyond a passing familiarity with the most prominent relationships and various author’s historical contexts, I hadn’t previously appreciated the deep, interconnected network of personal and philosophical relationships. The waves of history that brought these great philosophers together and ultimately tore them apart.

Phenomenology, which formed a basis for later existentialist thought, seeks to describe things as they are, as they present themselves. In this way, Bakewell’s book can be seen as a phenomenological study of generations of thinkers desperately exploring “how we can be free and behave well in a complicated world.” A world that saw two world wars, a massive calculated genocide, a showdown of super powers, and the threat of nuclear annihilation.

As someone interested in civil society, I see this question not simply as an individual one: how can I be free and behave well – but as a collective one: how can we all get along while wrestling with the challenges of being free and behaving well in a complicated world.

The story of the existentialist movement is one of carousing nights, passionate debates, and conversations at cafés. It’s a story of drinking, dancing, and sucking the very marrow out of life. It’s a story of being free.

But it’s also a story of fault and discord. Of unforgivable sins and spiteful fallings out. It a story of individuals struggling with the burden of what it means to be free: of trying to make the right choices and often making the wrong ones. Of people searching for what they stand for in difficult times – and breaking from those who disagree.

It’s a story of love and betrayal. Of betrayal and love.

The most notable villain in this story is Heidegger, whose Nazi activities make him still a controversial figure today. Elected rector of the University of Freiburg in 1933, Heidegger joined the Nazi party and was responsible for carrying out Reich law, including firing all Jewish professors and stripping emeritus faculty – such as his friend and former mentor Husserl – of their privileges. Heidegger’s personal notebooks from that time were published in 2014, revealing “philosophical thoughts alternating with Nazi-flavoured anti-Semitic remarks…Heidegger was a Nazi, at least for a while, and not out of convenience, but by conviction.”

Heidegger’s Nazism is topic much larger than this post, but needless to say, he fell out with his Jewish friends and colleagues. He rarely spoke with Husserl. In letters he tried to assure Hannah Arendt – for whom Heidegger had formerly been a lover – and mutual friend Karl Jaspers that he was not really a Nazi, but eventually they broke ties with him.

Edith Stein, who’d been a student of Husserl’s shortly before Heidegger, had converted to Christianity and joined a convent long before the war. She was detained, imprisoned , and murdered in a Nazi concentration camp.

But beyond the staggering actions of Heidegger, the story of existentialism tells of many more every day betrayals.

Emmanuel Levinas, another of Husserl’s students at a time of devotion to Heidegger, acted very much like a 23 year-old in 1929 following a debate between the magnetic Heidegger and old guard philosopher Ernst Cassirer. Cassirer’s wife, Toni, walked in on Heidegger’s students “satirically reenacting the debate.” Levinas played Cassirer, “dusting his hair with white talc and twirling it into a high quiff like an ice cream cone. Toni Cassirer did not find him funny. Years later, Levinas wished he had apologized to her for his irreverence.” Levinas – who was also Jewish – lost his love for Heidegger soon after.

Meanwhile, a tight-knit group of existentialists was forming in France. Simone de Beauvoir and her childhood friend Maurice Merleau-Ponty met Jean-Paul Sartre and his childhood friend Raymond Aron. Beauvoir and Sartre quickly became lovers and remained primary partners for the rest of their lives. In a Parisan café, under the burden of German occupation, the pair met Albert Camus. Hungarian scholar Arthur Koestler also joined their circle.

And as the dark days of the war faded, there was a golden time of love, friendships, and good natured but passionate debates.

But such times were short lived. Intellectually attracted to communism, but dismayed by fascist actions, the existentialists found themselves pulled in different directions. Was the promising vision of communism worth holding on to given the actions taken in its name? Were the actions of fascist states forgivable given the great good given as reason? Capitalism was deeply flawed and the U.S. had its own sins – so was siding with them really any better?

It was dark, dramatic times.

Koestler threw a wine glass at Sartre and got into a scuffle with Camus. Aron moderated a panel where he allowed Sartre to be verbally ganged up on. Camus wrote pointed pieces attacking the position of Sartre, who took no pause in firing back. Sartre attacked his old friend Merleau-Ponty, and they similarly fell out.

After the wine-glass incident, Koestler ran into Sartre and Beauvoir on the street – from a second hand account of Koestler’s point of view, Koestler suggested the three get together for lunch. “Koestler, you know that we disagree,” Beauvoir reportedly responded, “There no longer seems any point in our meeting.”

This is the fundamental question of civic life.

Can people who disagree so vehemently about such high stakes things continue to coexist in a civic sense? If not, the alternative is to avoid such matter – to stick to safe topics like the weather.

But that is a basic betrayal of civic duty. It may maintain friendships, but at the cost of moral questioning and action. Perhaps small topics are best to avoid – but when the big things are at stake – with the nature of the state and the future of the global world hang in the balance, simply not discussing these topics is not an option.

Sartre, Camus, Beauvoir, Merleau-Ponty, Koestler, and Aron had to take a stand. Their views, voices, and actions mattered. But they found their divergences unmanageable – they could not be friends.

This poses a tremendous challenge to the basic premise of civic life: that each of our voices matter, and that we all must find ways to productive share and debate our views.

KF & NIFI Launch Environmental Issues Forums, Host Webinar

The good folks with the Kettering Foundation and National Issues Forums Institute – both NCDD member organizations – recently launched a key partnership with the N. Am. Association for Environmental Education called Environmental Issues Forums, and we want our members to know about it. The program provides trainings, issue guides, online forums, and other resources for educators wanting to host deliberative forums about our changing climate. We encourage our members to learn more about this important effort here.

The team is hosting a webinar on Aug. 24 about how this program can be applied in higher ed, and we encourage you to register. Learn more in the NIFI blog post below or find the original here.

WEBINAR: Environmental Issues Forums & Higher Education

Join the North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE) for a webinar on Wednesday, August 24th, at 4:00 PM EDT!

Join the North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE) for a webinar on Wednesday, August 24th, at 4:00 PM EDT!

Climate change. Drought. Energy. Biodiversity.

How can we facilitate civic deliberation about controversial issues like these on our college campuses?

NAAEE and the Kettering Foundation created the Environmental Issues Forums (EIF) to help. Join this webinar to learn more about EIF, the newly published issue guide Climate Choices: How Do We Meet the Challenge of a Warming Planet?, and how faculty at UW Stevens Point and Eastern Kentucky University are integrating deliberations in their coursework.

Click here to register.

For more information about NAAEE’s Environmental Issues Forums, visit us online.

You can find the original version of this NIFI blog post at www.nifi.org/en/webinar-eif.

Bassendean Train Station – Enquiry-by-design

The Tension Between Preserving a Community and Protecting It

SOURCES at UCF Annual Conference Call for Proposals

I have had the great pleasure of attending the past two SOURCES conferences, and our Dr. Terri Fine and Dr. Michael Berson have presented there. I encourage you to consider attending this fantastic one day conference!

SOURCES Annual Conference

http://www.sourcesconference.com

University of Central Florida

Orlando, Florida

Saturday, January 14, 2017

The Teaching with Primary Sources Program at the University of Central Florida (TPS-UCF) is pleased to announce a call for proposals to present at the SOURCES Annual Conference at the University of Central Florida to be held on January 14, 2017. The SOURCES Annual Conference Program Committee welcomes proposals that focus on presenting strategies for using primary sources to help K-12 students engage in learning, develop critical thinking skills, and build content knowledge, specifically in one or more of the following ways:

• Justifying conclusions about whether a source is primary or secondary depending upon the time or topic under study;

• Describing examples of the benefits of teaching with primary sources;

• Analyzing a primary source using Library of Congress tools;

• Accessing teaching tools and primary sources from loc.gov/teachers;

• Identifying key considerations for selecting primary sources for instructional use (for example, student needs and interests, teaching goals, etc.);

• Accessing primary sources and teaching resources from loc.gov for instructional use;

• Analyzing primary sources in different formats;

• Analyzing a set of related primary sources in order to identify multiple perspectives;

• Demonstrating how primary sources can support at least one teaching strategy (for example, literacy, inquiry-based learning, historical thinking, etc.); and

• Presenting a primary source-based activity/lesson that helps students engage in learning, develop critical thinking skills and construct knowledge.

Inclusion in the SOURCES Annual Conference program is a selective process, so please be specific in your descriptions. It is important that you provide clear and descriptive language to assist the reviewers in their task. Professional attire is required for all presenters, and all sessions will last one hour. Proposals must be submitted by midnight on September 30, 2016, by using the following submission form: http://ucf.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_cLPHuj9feYKb0yN. If you submit a proposal, you will be notified, by the end of November, as to the committee’s decision regarding your proposal. If you have any questions or need any additional information, please contact Dr. Scott Waring (swaring@ucf.edu).

The Scale of Society

Deliberative processes work best at the local level. Modern tools make “local” less physically place-bound than it was in the past, but “local” is still a factor in the sense of small groups with some shared…culture – for lack of a better word

Deliberative processes aren’t impossible beyond this scope, but the locality of a discussion is important.

The extent to which a culture is shared by a group, for example, shapes the starting point of discussion. If participants speak different languages, a deliberation needs interpreters and participants need to get used to the cadence of an interpreted discussion. Perhaps this effect vanishes with high-end UN interpreters, but in my experience even simultaneous interpretation requires a little more thought and attention than a conversation in which everyone shares a native language.

Even if people share a language, deliberators may need to understand each other’s metaphors or specific terminology. This, in fact, is one of the things which makes interdisciplinary work so hard.

Finally, the extent to which people share values guides how much deliberation can accomplish. In particularly contentious communities, it is often enough for deliberation to get people to acknowledge each other’s shared humanity. Perhaps we will never agree, but we can still coexist in civil society together. In less contentious settings, deliberators may be able to design policy initiatives or determine budgetary expenditures. More cohesive groups are able to have more tangible outcomes.

Of course, you don’t want people in a deliberative group to have too much in common – deliberation among clones would be a particularly pointless exercise. But diversity of thought, experience, and language comes with real challenges which influence just how much deliberation can and should accomplish.

Locality also effects deliberation in terms of the size of a discussion. I cannot possibly deliberate simultaneously with everyone in my city. A deliberation needs to be “small” in some sense of the word. That smallness can come in the form of a face-to-face interaction, or a long-distance internet-mediated discussion. In larger settings, the intimacy of deliberation can also be accomplished by having a large room full of numerous small-group discussions. But each individual deliberation must be small.

“Good” deliberation, then, is by necessity a very local thing – undertaken by a small group of people and designed for the specific context and needs of that group.

This presents a challenge.

Philosopher Peter Singer urges us to abandon the false image of ourselves as members of a national community, in favor of conceptualizing ourselves as members of a global community. But such a thing is easier said than done.

Singer argues that “though citizens never encounter most of the other members of the nation, they think of themselves as sharing an allegiance to common institutions and values.” Since this is a symbolic association rather than a ‘real’ one driven by personal relationships, it should be simply a matter of mindset to change our symbolic associations to broader ones.

This is an appealing idea, but seems less and less feasible. At a time when national cohesiveness seems to be breaking down – even as nationalist sentiments rise – the vision of a unified world seems further than ever. As my own country becomes more polarized, I’m more inclined to share allegiance with my liberal peers around the world than with the more conservative citizens of my own country. This is not, I believe, the sort of global citizen Singer had in mind. It would be too generous to claim that my allegiance – as Singer calls it – has shifted not because I’ve virtuously come to see myself as part of a global human community. Rather, in an increasingly globalized world, my understanding of who is “like me” is simply different from previous conceptions. It is factions at a global scale.

This ties to the locality of deliberation because, in theory, you could have a small town run entirely deliberatively. I could envision a small community of people – from different backgrounds and even from different languages – effectively self-governing and learning to thrive with disagreement and civil conflict. Deliberation offers that kind of vision: the opportunity to bring people together, to build something greater than its parts.

But I’m not sure such deliberation could work on a global or even national scale. The scope is just too big.

There’s an increasing need for us to all conceive of ourselves as global citizens, to come together in the joint task of co-creating our world, but perhaps the task is just too great, the scale just too large.

Where Have All the Voters Gone?

The 6-page discussion guide, Where Have All the Voters Gone?, was created by the Maricopa Community Colleges Center for Civic Participation and Arizona State University Pastor Center for Politics & Public Service. It was updated in July 2016 and was adapted from National Issues Forums Institute. This discussion guide provides four approaches to use in deliberation on why voter turnout is currently low and has dramatically gone down since the 1960s, especially among communities of color. With each approach, the guide offers examples and suggestions; and concerns, trade-offs, and consequences. The end of the guide offers closing reflections on how participants’ thinking changed during the discussion and what can be done to remedy the low voter turn out in current US politics.

Below is an abbreviated version of the guide, which can be downloaded in full at the bottom of this page or found on NIFI’s site here.

From the guide…

Many Americans express frustration and concern about poor and decreasing voter turnout rates in local and national elections. Discussion about why citizens aren’t voting tends to focus on voter attitudes toward politicians and politics, and on the implications of a disengaged voting populace for the future of our democracy.

Given these concerns:

What, if anything, should be done to increase voter participation?

What are the key elements of a “healthy democracy”?

The discussion guide gives four options for deliberation:

Approach One: Eliminate the barriers

Proponents of this approach say that the act of voting has become too complicated and poses obstacles and barriers that can prove challenging for some voters to overcome. They suggest changes to the voting and elections system to make it easier and more convenient for voters to participate in elections.

Approach Two: Increase election issue awareness

Some research suggests that a major factor contributing to low voter turnout is a lack of awareness or familiarity with the candidates, positions, or ballot measures that will be voted on in a given election. Critics point out a declining emphasis on civics education in public schools as a cause for this trend. Others point to a vicious cycle for voters in communities that vote in low numbers: Candidates and campaigns focus efforts on communities that vote in high numbers. So minorities and poor voters, for example, get less information about elections, which leads to low turnout.

Approach Three: Reform the election process

Many voters and non-voters alike express concern and frustration about problems with the election and voting process. Some are concerned about security and accuracy issues relating to voter fraud and vote tabulation (“Will my vote even be counted?”), while others worry about the role and influence that the political party system, lobbyists and political campaigns have, and about the fairness and transparency of the election process.

Approach Four: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”

Some policy leaders argue that it is not necessary or even ideal for all citizens to participate in every election. They say that voters will participate in elections that have particular interest for them, and will perhaps endure the consequences for not voting, and that that is the nature of democracy.

To explore the full discussion guide with examples, suggestions, concerns, trade-offs, and consequences; click the link below.

About Maricopa Community Colleges Center for Civic Participation

The Maricopa Community Colleges’ Center for Civic Participation (CCP) seeks to enrich public life and public discourse on our Maricopa Community College campuses and in our communities. The Center also serves to promote effective practices that support Maricopa’s mission relating to community education and civic responsibility.

About Arizona State University Pastor Center for Politics & Public Service

Located in the ASU College of Public Service and Community Solutions, the Center serves as a dynamic, student-centric hub of activity that promotes, publicizes, and encourages political engagement and public service among ASU students and the broader community. It embodies ASU’s commitment to being an active agent of change, addressing society’s problems.

About NIFI Issue Guides

NIFI’s Issue Guides introduce participants to several choices or approaches to consider. Rather than conforming to any single public proposal, each choice reflects widely held concerns and principles. Panels of experts review manuscripts to make sure the choices are presented accurately and fairly. By intention, Issue Guides do not identify individuals or organizations with partisan labels, such as Democratic, Republican, conservative, or liberal. The goal is to present ideas in a fresh way that encourages readers to judge them on their merit.

Follow on Twitter: @NIForums

Resource Link: Where_Have_All_the_Voters_Gone

March 2016 Interview on MS Flag

The Commercial Appeal, March 12, 2016

I now recall giving an interview that I had completely forgotten about. As I had written on the MS state flag, a reporter called me from The Commercial Appeal, Memphis, TN’s major newspaper. To those not from the region, Memphis is the closest big city for many folks living in northern Mississippi. In fact, lots of people live in DeSoto, MS, and commute across the state border to work in Memphis. So, lots of Memphis readers are Mississippians.

In the effort to change the MS state flag, one approach that arose came in the form of a lawsuit. Here’s the piece that draws on the interview I gave.

In the effort to change the MS state flag, one approach that arose came in the form of a lawsuit. Here’s the piece that draws on the interview I gave.

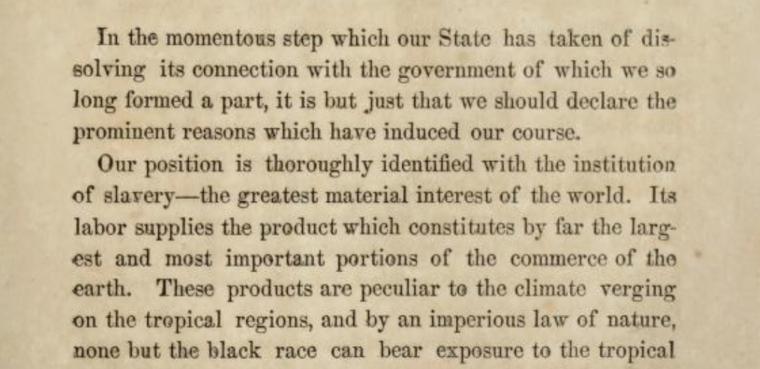

Still no change to the MS state flag. It bears an emblem of the Confederate Battle Flag in its canton, even though the state of Mississippi joined the Confederacy explicitly for the purpose of defending the institution of slavery. Go on, read it. Please.

Here’s the article in The Commercial Appeal about the lawsuit.

Authenticity and Social Selves

A few months ago, the New York Times ran an op-ed titled, Unless You’re Oprah, ‘Be Yourself’ Is Terrible Advice.

As author Adam Grant argues, our “authentic selves” would most likely do and say things that we – and everyone around us – would regret in the morning. Being true to yourself becomes rather ignoble if your authentic self is deeply flawed.

Rather than being authentic, Grant urges that we aim to be sincere. “Instead of searching for our inner selves and then making a concerted effort to express them…Pay attention to how we present ourselves to others, and then strive to be the people we claim to be.”

This is an interesting argument, but I’m not convinced there’s an inconsistency in being true to your authentic self and having a malleable social self.

First, dismissing the value of an authentic self seems to very much come from a position of privilege. If being authentic means nothing more to you than blurting out every thought that passes through your head, then your authentic self does not need to be found.

In Covering: The Hidden Assault on our Civil Rights, legal scholar Kenji Yoshino examines the disproportional social and legal pressures some people face to hide their authentic selves. And this ‘covering’ can do real, psychological damage. Our laws have come to protect people from certain overt forms of discrimination – you can’t fire someone because of the color of their skin or because of their gender. But, Yoshino points out, you can force them to cover.

You can forbid certain hairstyles, for example. In fact, it’s perfectly legal for employers to ban hairstyles predominately worn by African American women. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell banned service men and women from expressing their sexual identity for nearly 2 decades. Yoshino provides numerous other examples of legal precedent which supports the suppression of minority identities in favor of the norms of white, straight identity. (Yoshino also argues that women face the particular challenge of being told to “act like men” in the workplace while also being told to be ‘feminine’. Employers can even mandate that women wear makeup or otherwise alter their appearance.)

This is what I think of when I hear ‘authentic self.’ I don’t imagine there’s some isolated island of ‘me’ that I need to discover and remain statically true to in order to be virtuous. It means there are some elements of my identity which are fundamental to who I am, and losing those elements or having them submerged by society is harmful to me.

I don’t see such an idea as being in conflict with the idea I’ve been writing about much of this week: that a ‘self’ is more a reflection social interactions than it is an isolated entity.

A self can be co-created and still have distinctive qualities which are worth being authentic to.

I can joke with one group of friends and be serious with another; I can show different sides of myself and express myself in different ways. I can have different types of relationships with different types of people – and I can sometimes even keep my mouth shut so as to not say something inappropriate. None of that is inconsistent with being authentic. None of that is inconsistent with striving to be the best person I can be. And none of that is inconsistent with the idea that the core of who I am is formed, not as some Athena sprung from my head, but mainly by my interactions with others.