(Hartford, CT) One interpretation of Trump, Brexit, and related phenomena is that people fear losing their privileges and are reacting with prejudice against immigrants and racial and religious minorities. That thesis must contain a lot of truth. But a different–and compatible–interpretation is that large elements of the working class are revolting against an unjust but dominant political economy.

For instance, Harvard Professor Richard Tuck makes the leftist case for Brexit. Britain needed to leave the EU because “the essence of the EU is neoliberal. … The policies that are enshrined in its treaties and in its administrative structures are essentially those of the neoliberals.” Meanwhile, in the US, Trump holds a double-digit lead over Clinton among the working class as a whole, while he trails by similar margins among college-educated people–and the US Chamber of Commerce denounces his position on trade.

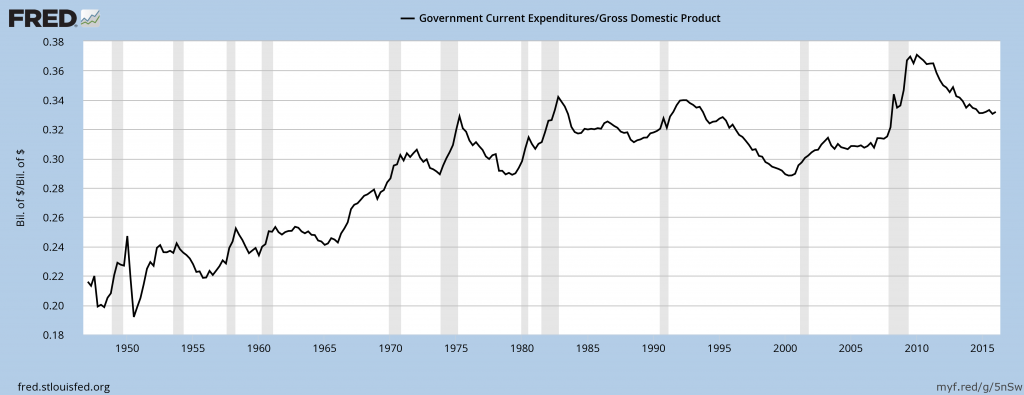

If the working class is rising up, what are they rising against? Hardly anyone calls himself a “neoliberal,” and critics load a lot of diverse ideas into that term. It presumably doesn’t mean libertarianism or laissez-faire, because then we could just use those words (dropping the “neo-“). What’s more, the US and EU have not moved in a libertarian direction. Here, for instance, is the trend in government spending as a percentage of GDP in the USA. It’s basically up, albeit with declines in the last six years of both the Clinton and Obama administrations.

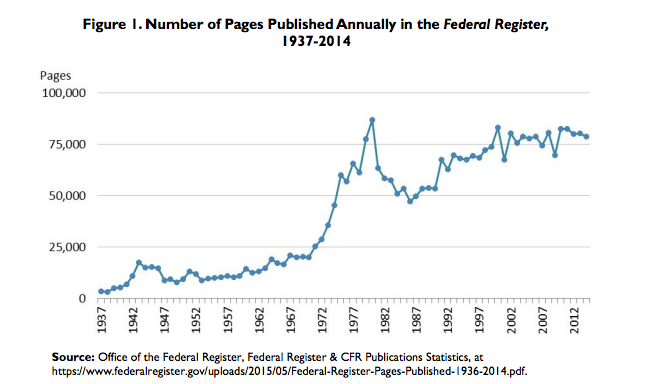

The volume of government regulation is also up, although that’s harder to measure. This is the size of the annual federal compendium of new regulations, measured in pages. A libertarian regime would not issue 80,000 pages of new rules per year.

There are many good things about regimes like the US and the EU member states. In broad, historical context, they are relatively free, prosperous, safe, and democratic. Nevertheless, I will emphasize the negatives, for much the same reason that your doctor wants to talk about your hypertension and family history of cancer, not how wonderfully well your liver and kidneys are working. In other words, I’ll offer a critical assessment even though there would also be many positive to points to make.

In brief, I think that states are increasingly powerful, but they are accountable to capital, not to citizens. That’s what critics mean by “neoliberalism,” although “state corporatism” might be a better phrase. I’ll break the diagnosis into six parts.

1. Deindustrialization

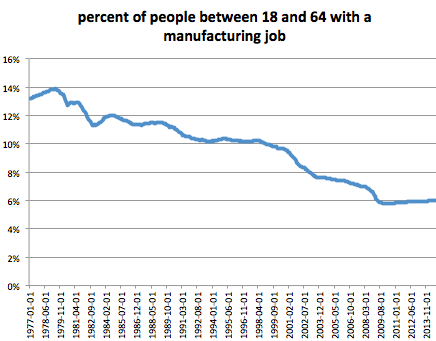

We call the wealthiest countries of the world the “industrialized” nations, but that description is becoming obsolete. These countries did industrialize after 1800 but have shed most of their manufacturing jobs. Below is the trend for the US since 1977. The graph understates the decline, because many more than 14% of households had at least one manufacturing worker, usually a man, in 1978. Also, the rate was higher in 1950, but I can’t find a longer time series. In any case, the decline since 1977 has been steep.

Manufacturing jobs are rarely enviable, but they give their workers political leverage because they require expensive, fixed investments. Ford’s River Rouge plant in Detroit employed 100,000 men at its peak (versus 6,000 people today). Autoworkers could organize and strike. They voted in city and state elections. It was expensive for Ford to move its investments out of Detroit, although that gradually happened, and the city has lost 61% of its population. But in the heyday of industrialization, Ford needed those men to be reasonably happy. In return, manufacturing workers benefitted from their political leverage–including Black workers, whose civil rights improved with their concentrated market power in factories.

By contrast, Google, which is worth about half a trillion dollars, employs some 50,000 people, worldwide. They are well paid, but they remain at Google for a median of 1.1 years. They have market value–far above the average market value of average Americans, let alone average human beings–but they have little or no political leverage. Even the best-paid are dispersed, transient, and eminently replaceable.

2. Mobile capital

The fact that you can now make more money by investing in intellectual property and networks rather than rooted industries is one reason that capital moves faster than ever before. Capital mobility is also encouraged by favorable laws and treaties and by financial instruments, analytics, and other tools that assist investors.

The result is a substantial increase in the leverage of capital even as the leverage of labor has weakened. Businesses gain their “privileged position“–even in democracies with free and fair elections–from two major sources. First, since a business is organized, it can deliberately advocate for its interests by lobbying or advertising, whereas diffuse interests (like consumers or workers) have much more trouble acting politically. Second, investments are essential for prosperity, and a business can move its investments. Thus, even without lobbying at all, a business–or an individual investor–gains leverage over governments. Its ability to invest and or disinvest gives it power. That power has rapidly increased. It also reinforces …

3. Deference to wealth

This point is harder to quantify, but I perceive that we live at a time when billionaires, celebrities, and CEOs are given extraordinary deference, especially in comparison to run-of-the-mill elected officials, civil servants, union leaders, and grassroots organizers. Politicians, for instance, are constantly in contact with their wealthiest constituents. First-year Democratic Members of the House are advised to spend four hours per day of every day calling donors. Meanwhile, many advocacy groups are funded by rich individuals, not sustained by membership dues, so their leaders are also constantly on the phone or at conferences and meetings with wealthy people. The conversations in these settings tend to be deeply deferential, and they occur behind closed doors. Of course, these habits are abetted by laws and policies–especially, laws governing campaign finance in the US. But we observe somewhat similar deference in other countries with better laws. I think the deeper cause is the shift of leverage to economic elites.

4. The market colonizes the public sphere

“Commonwealth” is a translation of “republic,” which could be more literally rendered as “the public’s thing.” In a republic, the government is supposed to be distinct from the private sector. As the custodian of the common wealth, it operates on different principles from a market. These principles are not simply majoritarian, for the commonwealth belongs to our unborn children as well to us. We have no right to waste it by voting for the wrong policies. A republic strives to define and implement something worthy of the title “public good.”

That distinct ethic has been lost, as governments are almost universally seen simply as service-providers, constantly compared to businesses on the grounds of efficiency, and expected to compete in a market for popularity and influence. In a 1870 case, the Supreme Court declared a lobbyist’s contract void on the ground that it would be “steeped in corruption” and “infamous” for any business to hire someone “to procure the passage of a general law with a view to the promotion of their private interests.” The Court added:

The foundation of a republic is the virtue of its citizens. They are at once sovereigns and subjects. As the foundation is undermined, the structure is weakened. When it is destroyed, the fabric must fall. Such is the voice of universal history. The theory of our government is that all public stations are trusts, and that those clothed with them are to be animated in the discharge of their duties solely by considerations of right, justice, and the public good.

We certainly didn’t live up to those words in 1870s, when government was in many ways more corrupt than it is now. But the animating philosophy of a public good was still alive then. In contrast, Buckley v Valeo (1976) defines political money as constitutionally protected speech, and Citizens United (2010) equates businesses with civic associations. These are examples of a general erosion of a distinction between public good and private interests.

5. States have increasing power

If we lived in a neo-“liberal” or laissez-faire era, states would be constrained. In some ways, they are, but they also have more access to data about people than ever before; they have an easier time surveilling, influencing, punishing, and even killing individuals; and they operate increasingly powerful systems for enforcing discipline, headlined by the vast prison system of the USA. Their ability to see, count, and act also extends far beyond their borders, making people in most parts of the world subject to more than one government at once.

6. But states need their citizens less

On the other hand, states don’t need their own citizens. They don’t need us as military conscripts, because they can fight using small numbers of highly equipped experts, and they don’t need most of us as taxpayers, because they can finance their operations on international markets.

Mitt Romney did himself no favors by accusing 53% of Americans of being “takers” instead of “makers.” (Also, his numbers were off, since he omitted people who pay payroll taxes.) But he was right that a small minority can finance a modern government, which means that the state really doesn’t have to pay much attention to the rest of its people.

Put those six premises together, and you would predict a political regime in which investors use an expansive and intrusive state to promote their own interests. This seems almost precisely accurate as a description of regime like China’s, and all too apt when applied to the US, the UK, or the EU as well. It doesn’t excuse voting for Donald Trump, who offers no alternative and threatens fundamental rights. I don’t think it offers a very good rationale for Brexit, either. But it does explain why a political class wedded to this status quo would face an electoral insurrection.

You are invited to join one of two upcoming online forums to deliberate about Energy Choices as part of a new Environment and Society series of forum materials that will be available for people to use in their communities. The online forums will use the Common Ground for Action platform.

You are invited to join one of two upcoming online forums to deliberate about Energy Choices as part of a new Environment and Society series of forum materials that will be available for people to use in their communities. The online forums will use the Common Ground for Action platform.