The Florida Joint Center for Citizenship is quite proud to be a member of Florida’s Partnership for Civic Learning. One of the most promising research projects that the Partnership has undertaken is to explore the role of classroom experience in student civic participation. In other words, are students more likely to engage in civic life if they learn about civics in a classroom with a variety of instructional practices? This is a question that we believe deserves an answer, as it can help districts, schools, teachers, and other stakeholders what quality civics instruction should look like. And it is such an important one for Florida and the nation.

In the spring of 2015, the Lou Frey Institute administered the Civic Attitude and Engagement Survey to 7th grade students enrolled in Miami-Dade, Clay, and St. Lucie County schools here in Florida. 7,436 students in 75 middle schools across these three districts were surveyed. It should be pointed out here that a huge amount of the data sample was drawn from Miami-Dade schools, in part because of certain time and district issues. 88% of the schools that took part were in Miami-Dade, 10.7% in Clay County, and 1.3% in St. Lucie County. We are grateful to all those that participated.

The survey itself consisted of 20 items of question blocks that focused on a number of areas connected to civic attitudes, knowledge, dispositions, and engagement. Ultimately, we want to provide districts with a tool that would connect completion of Florida’s 7th grade civics course to student (1) civic proficiency and readiness for future engagement as informed citizens; (2) commitment to democratic values and rights; (3) knowledge of current events; (4) efficacy/self-confidence about one’s ability to contribute to society; and (5) experience with recommended pedagogies for civics. We hope to expand the number of participants in this survey, and to provide this as a yearly examination of what is happening in civic education classrooms.

So, what did this first offering of the survey find? Let’s take a look.

Learning in Classroom

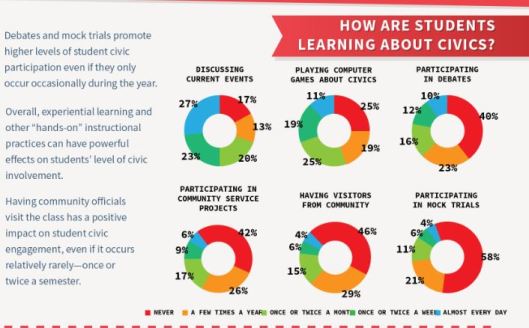

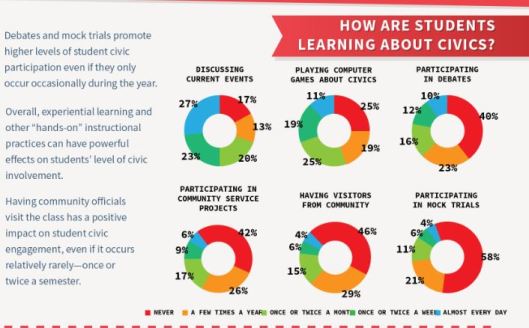

This is, perhaps, no surprise. The more students are engaged in the practices of civic life through classroom instruction, the more they are likely to engage in the practices of civic life outside of the classroom. Of course, there are caveats that must be taken into account when considering this data. For example, it is highly unlikely that 10% of students are taking part in debates every day. I do not find it surprising however that 40% of students said that they NEVER engage in debate in the classroom, and that 58% of students never participate in a mock trial (though students in Florida are SUPPOSED to experience the jury process. See SS.7.C.2.3—Experience the responsibilities of citizens at the local, state, or federal levels) . In my experience, some teachers are uncomfortable with the structure of debates and simultations and the possibility that there could be controversial (and possibly job-threatening, especially in a state with no tenure) topics involved. And of course, there is the time factor!

This is, perhaps, no surprise. The more students are engaged in the practices of civic life through classroom instruction, the more they are likely to engage in the practices of civic life outside of the classroom. Of course, there are caveats that must be taken into account when considering this data. For example, it is highly unlikely that 10% of students are taking part in debates every day. I do not find it surprising however that 40% of students said that they NEVER engage in debate in the classroom, and that 58% of students never participate in a mock trial (though students in Florida are SUPPOSED to experience the jury process. See SS.7.C.2.3—Experience the responsibilities of citizens at the local, state, or federal levels) . In my experience, some teachers are uncomfortable with the structure of debates and simultations and the possibility that there could be controversial (and possibly job-threatening, especially in a state with no tenure) topics involved. And of course, there is the time factor!

It is important to note having even one visitor from the community seemed to have a positive impact on broader civic engagement. This suggests to us that perhaps the FJCC should work on making that more possible (hint: we are).

Best Bang for Your Buck

So, what sorts of activities did seem to have the greatest impact on promoting student engagement? Preliminary review and analysis of survey data suggests that, as mentioned above, having a visitor from the community come to a class was huge. These visitors, of course, should be connected in some way to civic life (perhaps a mayor, city manager, council member, school board member, elections supervisor, etc). Naturally, actually participating in some sort of civic project was huge, as students are more likely to continue engaging in civic life once they have been out in the community. Personally, I expected a greater correlation with playing civics-oriented games (in this case, likely to have been iCivics), but I suspect that some of that could depend on how the game is actually used in class, and how often it is used. This is an area for further research on our part.

Best Practices

Best Practices in Civics, at least according to the most recent research from our friends at CIRCLE , Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, and others, tends to emphasize the Six Proven Practices in civic learning:

1. Classroom Instruction: Schools should provide instruction in civics & government, history, economics, geography, law, and democracy. Formal instruction in these subjects increases civic knowledge and increases young people’s tendency to engage in civic and political activities over the long term. However, schools should avoid teaching only rote facts about dry procedures, which is unlikely to benefit students and may actually alienate them from civic engagement.

2. Discussion of Current Events and Controversial Issues: Schools should incorporate discussion of current local, national, and international issues and events in to the classroom, particularly those that young people view as important to their lives. When students have an opportunity to discuss current issues in a classroom setting, they tend to have a greater interest in civic life and politics as well as improved critical thinking and communication skills.

3. Service-Learning: Schools should design and implement programs that provide students with the opportunity to apply what they learn through performing community service that is linked to the formal curriculum and classroom instruction.

4. Extracurricular Activities: Schools should offer opportunities for young people to get involved in their schools or communities outside of the classroom. Studies show that students who participate in extracurricular activities in school remain more civically engaged then those who did not, even decades later.

5. School Governance: Schools should encourage meaningful student participation in school governance. Giving students more opportunities to participate in the management of their classrooms and schools builds their civic skills and attitudes.

6. Simulations of Democratic Processes: Schools should encourage students to participate in simulations of democratic processes and procedures. Evidence shows that simulations of voting, trials, legislative deliberation and democracy, leads to heightened civic/political knowledge and interest.

As the chart suggests, engaging students in a greater number of school and classroom-oriented civic practice opportunities tends to encourage greater engagement. Is there a point at which we receive diminishing returns however? Do students who might otherwise fall on the low end of civic engagement suddenly jump to moderate or high levels if they take part in all six elements of the proven practices? Just how can we get a control group for this? No one wants to, not should they want to, provide future citizens with a lower quality civic education for the sake of further research. Nonetheless, this remains an area of inquiry that we need to further explore.

Outcomes

So, what does it all mean. Basically, engaging students in civic practice, even to a low degree, encourages further participation within the broader community! Now, we must consider that all of this information we have discussed relies on self-reported student data, and the Lake Woebegon Effect should always be in the back of our minds. Still, there are promising methods which can encourage greater student engagement in civic life; teachers just need to do them, and curriculum should be written in such a way that we give students that opportunity.

This is, certainly, a great deal to take in. The Partnership for Civic Learning is eager to continue this research and to see how these findings compare to data gathered from the next iteration and administration of the survey, especially outside the three districts that took part here. We are in the process of developing a brand new website that will share Partnership for Civic Learning research and projects, and this post will be updated to reflect where you can find this entire infographic, among other things.

This is, perhaps, no surprise. The more students are engaged in the practices of civic life through classroom instruction, the more they are likely to engage in the practices of civic life outside of the classroom. Of course, there are caveats that must be taken into account when considering this data. For example, it is highly unlikely that 10% of students are taking part in debates every day. I do not find it surprising however that 40% of students said that they NEVER engage in debate in the classroom, and that 58% of students never participate in a mock trial (though students in Florida are SUPPOSED to experience the jury process. See SS.7.C.2.3—Experience the responsibilities of citizens at the local, state, or federal levels) . In my experience, some teachers are uncomfortable with the structure of debates and simultations and the possibility that there could be controversial (and possibly job-threatening, especially in a state with no tenure) topics involved. And of course, there is the time factor!

This is, perhaps, no surprise. The more students are engaged in the practices of civic life through classroom instruction, the more they are likely to engage in the practices of civic life outside of the classroom. Of course, there are caveats that must be taken into account when considering this data. For example, it is highly unlikely that 10% of students are taking part in debates every day. I do not find it surprising however that 40% of students said that they NEVER engage in debate in the classroom, and that 58% of students never participate in a mock trial (though students in Florida are SUPPOSED to experience the jury process. See SS.7.C.2.3—Experience the responsibilities of citizens at the local, state, or federal levels) . In my experience, some teachers are uncomfortable with the structure of debates and simultations and the possibility that there could be controversial (and possibly job-threatening, especially in a state with no tenure) topics involved. And of course, there is the time factor!