We Must Demand Professional Policing For All

I am a professional philosopher. That doesn’t just mean I do it for a living. Though I’m glad to be paid for my work, getting paid to do a thing does not make you a professional. Being a professional means that philosophy is my vocation and is closely tied to my self-identity. The norms of my profession have become personal norms; when my profession suffers a crisis, I feel it personally. Even if I lost my job I’d think of myself as a philosopher!

Yet most police officers are not professionals in this sense. Consider the collective horror, shame, and disgust we philosophers have at the abusive behavior of our fellow philosophers: think of what it means to be compared to Colin McGinn or Thomas Pogge. Why isn’t there that kind of horror, shame, and disgust among police officers at the drumbeat of police shootings?

Some police departments do have professional police departments. I’ve written before (for instance here and here) about my work doing civilian oversight of the NYPD, where–for the most part–I observed professionals at work. Yet even there the culture tends to be defensive rather than proactive. They saw civilian investigators as a no-longer-necessary evil, based on long-past departmental misdeeds. Yet we did that work precisely because the department had failed to engage in its own oversight. And corruption and abuse kept appearing, like whack-a-mole, whenever a part of the department found itself unsupervised.

Still, the culture at the NYPD seemed to be slowly changing, and I met many young officers who took their work seriously and evinced a desire for more than an exoneration; they aimed not just to mount a vigorous defense of the legality of their actions, but also to show that they had acted wisely and well, and that failures to do so were blameworthy even if they were not punishable.

I do not see that professionalism in the Baltimore Police Department. It’s quite obvious that the police department in Baton Rouge is not professional in this way. And we now know far too much about the unprofessionalism–indeed the thuggery and extortion–of the Ferguson police department. The list of such unprofessional departments is almost as long as the list of African-Americans killed during routine interactions that would never have led to violence with whites. And that’s just it: the one common feature seems to be that the unprofessional departments are primarily policing African-Americans.

I won’t pretend to give #BlackLivesMatter activists advice; their movement has its own leadership and needs nothing from me. But white citizens are and ought to be outraged by these killings as well, so it’s time for us to think about what kinds of changes to demand. We have a responsibility here and we cannot shirk it merely because we are not citizens of the specific cities or residents of specific neighborhoods that suffer under the boot of unprofessional departments. We must do what we can to professionalize the departments that police our fellow-citizens.

This will be a multi-pronged effort. Some parts will be legal, for instance, adopting a necessity rule:

Even when the police have a reasonable belief that a person is dangerous, the necessity standard does not permit deadly force if non-deadly or less deadly alternatives are available and adequate to meet the threat.

(And yes, the reason many officers are exonerated for their killings is because their states do not require that their use of force be necessary. That’s disgusting.)

We must also change training to emphasize defusing violence before it starts:

The key for the police in such circumstances is to slow things down: to ask questions rather than bark orders, to speak in a normal tone, to summon additional resources if necessary. Pulling out a gun on an anxious person may unintentionally raise his level of stress. In “suicide by cop” confrontations, this can make a bad situation worse.

Finally, we have to change the norms and cultures of law enforcement in the United States, specifically the sense that police departments give their officers that they are besieged by the public and must form a “blue wall of silence.” Law enforcement officers have strong professional norms against whistle-blowing and go further, even covering up each others’ misdeeds. This has become a professional norm of non-judgment of the behavior of officers when they are criticized by outsiders.

This is organized corruption at the national level. The more professional police departments are complicit just because they fail to deplore the activity of their less professional fellow officers. Police departments must respond to criticism by changing their collective attitude to each other and their jobs; they must change their culture. Right now, officers respond to criticism by saying or thinking that “Civilians can’t understand split second decisions.” This is that defensive move. They must become pro-active and use their own professionalism publicly. They must look at videos like the ones that show Alton Sterling being shot, and join in the criticism of those acts. They must say: “Officer, your job is to make split second decisions well and you have failed.”

Remember this article? “I’m a cop. If you don’t want to get hurt, don’t challenge me.”

Don’t argue with me, don’t call me names, don’t tell me that I can’t stop you, don’t say I’m a racist pig, don’t threaten that you’ll sue me and take away my badge. Don’t scream at me that you pay my salary, and don’t even think of aggressively walking towards me.

This is what complicity looks like. Officer Sunil Dutta literally claims that calling him a “racist pig” is an excuse for him to use force; Sunil Dutta isn’t white, and that’s the only reason he will say this publicly. Yet he shares this position with many racist white officers, and thus provides them cover.

Police shootings must become not just a national embarrassment among liberals like me; they must be a professional embarrassment for everyone in law enforcement. Police officers should feel personally responsible to make #notallcops true; they should feel on the hook for proving the claim that “these abuses are outliers.” They must come to think that their honor is at stake, and that each and every shooting causes them dishonor.

So the norms of the law enforcement profession must change, and police themselves are unwilling to change them. Thus it falls to us, as citizens, to demand professionalism on our terms. We do pay their salary, and we are accountable for what our employees have done.

That means treating de-escalation and stricter rules of engagement as professional norms, and refusing to defer to law enforcement’s own norms of professionalism. We must conclude that unprofessional departments require civilian oversight, if even the professional departments need it. We must demand that our police departments begin building these new norms into officer training. We must demand that police departments replace the culture of the blue wall of silence with collective professional honor and shame.

The old saying, “Who watches the watchmen?” has an answer: democratic citizens watch. But we must stop merely watching, and act. We must work together to police the police.

Democracy by Design

The 8-page article, Democracy by Design (2014), by Nancy Thomas was published in the Journal of Public Deliberation: Vol. 10: Iss. 1. Thomas puts forth, Democracy by Design, which offers the framework for evolving democracy into one that is more robust and truer to the core tenets of the concept of democracy. This framework has four major foundations in order to have a better democracy: active and deliberative public participation; freedom, justice, and equal opportunity; an educated and informed citizenry, and; effective government structures. It was co-created by Thomas, the Democracy Imperative, Deliberative Democracy Consortium, the Campaign for Stronger Democracy, the Kettering Foundation, Everyday Democracy, CIRCLE, and the New England Resource Center for Higher Education.

Below is an excerpt from the article and you can find the PDF available for download from the Journal of Public Deliberation site here.

From the article…

American democracy works better when all citizens (referring to residency, not legal status) possess the knowledge, skills, social networks, and inclination, and have the opportunity, to address difficult public problems together.

In this essay, I make the case for connecting the kind of public engagement reviewed in this Special Issue with a broader reform agenda, what I will call Democracy by Design. It is a pragmatic and relatively simple framework for a robust democracy, consisting of four foundations: active and deliberative public participation; freedom, justice, and equal opportunity; an educated and informed citizenry, and; effective government structures. The language “by design” suggests a framework for democracy, not just disconnected mechanics, intentionally crafted and integrated for positive social consequences. I developed this concept, captured in the graphic below, as a road map for undergraduate education for democracy. Exploiting Thomas Huxley’s adage “learn something about everything and everything about something,” I propose that college students (and all Americans) should learn this framework or a version of it to fulfill their obligation to know “something” about how democracy works. And by the time they graduate, college students should know “everything” about at least one dimension of one of the four foundations (one “small box”).1 Democracy by Design is a work-in-progress, open to discussion, critique, and improvement.

Active and Deliberative Public Participation

Much has been written about the so-called crisis in civic life and the decline of social capital, of associations, trust, and norms that enable public problem solving. Robert Putnam’s compelling image of Americans “bowling alone” rather than in leagues captured concerns over declining engagement in faith communities, nonprofits, PTAs, labor unions, and the like. He and many others rallied civic leaders, policy makers, and educators and arguably spurred an industry concerned with measuring and improving civic life. Emerging around the more localized civic renewal efforts, grass-roots problem solving, such as the healthy communities movement and local crime prevention efforts. Old organizations (e.g., fraternal orders and women’s leagues) were replaced with issue-driven coalitions (e.g., child advocates and immigration organizations). Alongside these efforts and deeply embedded in the best of them has been deliberative democracy—informed citizens with diverse life experiences and perspectives coming together, exchanging viewpoints, deliberating choices, and collaboratively implementing fair solutions, with and without government involvement.

…

The challenge may be in knowing when to employ more deliberative versus more active approaches, or, stated another way, when to remain neutral. On this point, I would argue that advocates of public participation should never be neutral about the foundations of a robust democracy.

Freedom, Justice, and Equal Opportunity

Freedom to prosper and freedom from an overly intrusive government seem well-understood in American society, but I question whether the same holds true for other core American principles of justice and equal opportunity.

…

Power dynamics may persist because the dominant culture has projected its particular way of seeing social and political norms and systems so successfully that that view has become the natural order, even by those disempowered by it (Tong, 1989). This problem is stickier than overt oppression, individual bigotry, or discrimination. As a result, well-meaning people maintain the status quo, usually unconsciously, by going about their business without realizing the implications (Adams, et. al. 1997, 11).

We can’t be neutral about giving people an equal opportunity to participate in and shape the social, political, and economic systems that affect their lives. Advocates for active and deliberative engagement need to be attentive to power dynamics, structural inequality, and unconscious privilege. If we don’t, we risk becoming those well-meaning people who unconsciously perpetuate the status quo.

An Educated and Informed Citizenry

Few people question the value of quality public education, liberal and civic learning, free speech, an impartial press, and an attentive citizenry able to examine and critique information. Unfortunately, our public education system is not educating for citizenship.

…

Deliberation advocates lament their inability to get to scale, to make active and deliberative public participation the norm in American society. Imagine how much easier that task would be if students at all levels learned through discussion. Discussing controversial issues emerged in CIRCLE’s research as a high impact practice in civic learning at the K-12 level (Kawashima-Ginsberg, 2013). And studies show that students learn better through inquiry and discussion (McKeachie, 1994; Hess, 2009, 18). Everyday citizens without expert knowledge are capable of public reasoning. The task of engaging citizens would be easier if Americans developed the habits of active and deliberative citizens while in school and college.

Effective Government Structures

We need to change the way campaigns are financed, restore transparency and accountability to government, and flip power back to American citizens. At a conference in June 2014, Bob Brandon of the Fair Elections Legal Network lamented, “We have a system in which politicians select their voters rather than voters selecting their politicians.” Gerrymandering, long lines, registration problems, poorly formatted ballots, suppression efforts, and money in politics persist despite the tireless efforts of reform advocates. Only about half of eligible voters actually vote in federal elections (roughly 60% in presidential elections and 40% in mid-term elections).

Download the full article from the Journal of Public Deliberation here.

About the Journal of Public Deliberation

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen friendly form.

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen friendly form.

Follow the Deliberative Democracy Consortium on Twitter: @delibdem

Follow the International Association of Public Participation [US] on Twitter: @IAP2USA

Resource Link: www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol10/iss1/art17/

NCDD2016 Session Proposal Deadline Extended!

As we hope you’ve heard, we announced that we were opening the call for NCDD2016 conference session proposals earlier last month. We’ve had lots of great proposals come in so far, and we thank everyone who has submitted session ideas so far!

We’ve also received quite a few requests this week for extensions as folks firm up ideas and finalize plans with collaborators, so in honor of all the hard work our members are doing to make the conference an amazing experience, we are extending the deadline for session proposals! We are now accepting submissions until the end of the day on Wednesday, July 13th!

We’ve also received quite a few requests this week for extensions as folks firm up ideas and finalize plans with collaborators, so in honor of all the hard work our members are doing to make the conference an amazing experience, we are extending the deadline for session proposals! We are now accepting submissions until the end of the day on Wednesday, July 13th!

If you’re rushing to finish up a proposal, you’ve got a few more days now, but don’t delay! There is going to be some stiff competition for session spots this year.

If you’re still looking for collaborators on your sessions, you can review the calls for session partners that some of our members have put out on our NCDD discussion listserv checking out the discussion topics from the last few weeks in our listserv archives – you could also join the listserv and ask for collaborators yourself!

We recommend that you read over the initial call for proposals one more time before submitting, but once you’re ready, visit the Application Form and submit your proposal!

We look forward to seeing all of your great ideas!

Again.

I got confused while watching the news this morning.

There was grainy cell-phone footage of a black man shot by police. But the details were all wrong.

This wasn’t a story about Alton B. Sterling, a 37-year-old man in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, who was shot multiple times by police early Tuesday morning. He’d been engaged in the dangerously criminal act of selling CDs in front of a convenience store.

This was the story of Philando Castile, a 32-year-old man in Minnesota who was shot four times by a police officer Wednesday night while his girlfriend and young daughter looked on. He’d been reaching for his license, as the officer had requested.

In a powerful New York Times opinion piece yesterday, Roxane Gay expressed the anger and frustration many of us feel; the pain and fear felt acutely by people of color in this country:

I don’t know where we go from here because those of us who recognize the injustice are not the problem. Law enforcement, militarized and indifferent to black lives, is the problem. Law enforcement that sees black people as criminals rather than human beings with full and deserving lives is the problem. A justice system that rarely prosecutes or convicts police officers who kill innocent people in the line of duty is the problem. That this happens so often that resignation or apathy are reasonable responses is the problem.

It’s overwhelming to see what we are up against, to live in a world where too many people have their fingers on the triggers of guns aimed directly at black people. I don’t know what to do anymore. I don’t know how to allow myself to feel grief and outrage while also thinking about change. I don’t know how to believe change is possible when there is so much evidence to the contrary. I don’t know how to feel that my life matters when there is so much evidence to the contrary.

I am tired of writing this blog post. Tired of chronicling the deaths of too many people of color. Police killed at least 346 black people in the U.S. in 2015. Sometimes I want to just look away.

Of course, looking away is a luxury – it would never be me shooting that cell-phone footage; watching my boyfriend die in the back seat of my car while my daughter looks on; finding the strength to narrate while an officer points his gun through my window. That would never be me.

I was struck by something a Minnesota official said in response to the shooting of Castile. He was visibly shocked. “Things like this don’t happen here.” ….”Often.”

That sentiment strikes me as the problem.

I’d like to think that something like this would never happen in my city. That if I ever witnessed such a horror I would jump in and save the day. But ignoring the fact that I’d more likely be frozen and dumbfounded – this brutality doesn’t need heroes. It needs deep, systemic, and collective change.

Until then, these deaths will continue to happen everywhere. Black men will keep dying.

Earlier this week, the Center for Popular Democracy and Policy Link, in partnership with protesters and street-level organizers released a report detailing what cities and towns can do to end police brutality.

Mic has a good write up synthesizing 15 concrete steps citizens and local governments can take to affect change. I recommend reading their article and reviewing the report, but here are the 15 actions every municipality should take. This is how change happens:

1. Stop criminalizing everything.

2. Stop using poor people to fatten city budgets.

3. Kick ICE out of your city.

4. Treat addicts and mentally ill people like they need help, not jail.

5. Make policy makers face their own racism.

6. Actually ban racist policing.

7. Obey the Fourth Amendment.

8. Involve the community in big decisions.

9. Collect data obsessively.

10. Body cameras.

11. Don’t let friends of the police prosecute the police.

12. Oversight, oversight, oversight.

13. No more military equipment.

14. Establish a “use of force” standard.

15. Train the police to be members of the community, not just armed patrolmen.

Citrus Ridge: A New PUBLIC SCHOOL Civics Academy in Florida

Over the past few months, the Florida Joint Center for Citizenship has worked with teachers, administrators, and district leaders in Polk County to help with the creation of a brand new public school, one dedicated to K-8 civic education: Citrus Ridge.

Citrus Ridge, created with the support of local Congressman Dennis Ross, is a K-8 institution that will embed civic learning and civic life throughout school governance, relationships, and curriculum.

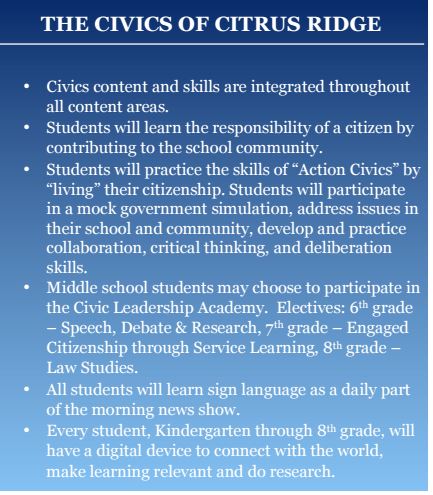

Citrus Ridge’s very mission statement is centered around civics and the importance of civic life:

- Community

- Inclusion

- Variety

- Innovation

- Collaboration

- Success

Our own Valerie McVey and Peggy Renihan, as well as our Teacher Practioners in Residence, have been heavily involved in the planning and work with Citrus Ridge. Last week, I had the pleasure of attending the first leadership team meeting for the school, and it was a great joy to see these teachers and administrators hard at work in learning about and understanding how the emphasis on civic life makes Citrus Ridge a unique public school.

A heavy emphasis was placed on ensuring that school culture reflects that civic engagement and civic learning.

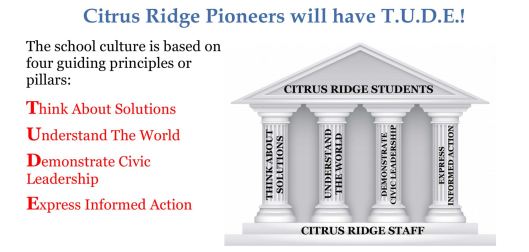

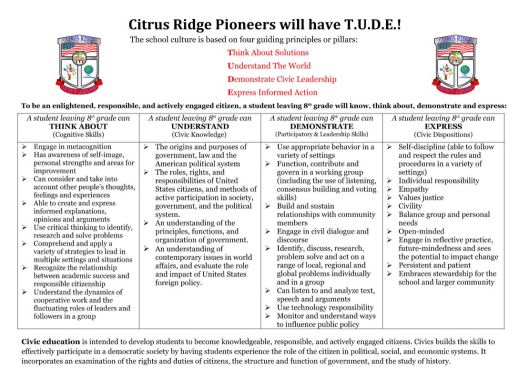

T.U.D.E aligns well with both the C3 Framework and with the Six Proven Practices of Civic Education, both of which will play a role in the curriculum and instruction of the school.

So what exactly is T.U.D.E? These principles draw on a number of sources for inspiration: the state of Florida’s civics benchmarks, the C3 Framework, the Six Proven Practices, and others. Take a look at them below. How do you see them reflecting the importance of civic knowledge, civic skills, and civic dispositions?

Most excitingly, we are in the process of finding ways to integrate the concept of action civics into the school and curriculum. It will involve students in addressing problems within their school and community, developing the skills of citizenship such as collaboration, critical thinking, deliberation, and discussion, and encourage students to ‘live’ their citizenship. Some examples are: providing towels for an animal shelter, discussing more recess time versus special area versus free choice, deliberating the school dress code, and thinking critically about the causes and effects of current event that effects our community, state, or nation. Indeed, our new action civics coordinator (reviewing applications now!) will spend a great deal of time at Citrus Ridge as we start to launch this school into the civic stratosphere.

There is so much more to say and do concerning Citrus Ridge: A Civics Academy. We will keep you updated as we get closer to the start of the year and into the new school year. FJCC is excited and grateful for the opportunity to work with some excellent people on this, and let me just thank all of the team that has worked so hard to get this off of the ground. It is a great step forward for civic education in Florida and, we hope, it will be a model for this state and the nation!

Process-Model Utopia

In The Task of Utopia, Erin McKenna argues in favor of a “process-model” of utopia. This vision is built largely upon the work of John Dewey, who dreams of democracy “as a method of living by which individuals are fully engaged in the experience that is their lives.”

We must move away from considering “end-state” models of utopia as a perfect, static, society and instead embrace our role as critical builders and shapers of our future world and selves.

For one thing, a static utopia is simply unattainable: “Social living is an ongoing process, not a perfected life. No harmony is lasting. Each satisfying moment passes over into a new need for which we must alter our world and/our ourselves to meet.”

But more deeply, a static vision strips people of their agency, takes away what really makes us alive. If an end-state utopia were achieved, there would be nothing for people to do, they’d have no role to play in perfecting themselves or perfecting their future. Any change could only represent a move away from perfection.

While that may be a small price to pay for establishment of utopia, McKenna argues that “the unfolding of the future is not determined separate from us, but is intricately connected with us.” Nearly by definition, an end-state utopia is not sustainable: across generations, people must continually work to sustain utopian institutions, but without a process-model there is no way to prepare future generations for this important task.

This idea fits well with Dewey’s model of democracy which, as McKenna writes, “requires that we recognize how our participation affects what the future can be. It requires that we recognize that there is no-end state at which we must work to arrive, but a multiple of possible future states which we seek and try out. John Dewey’s vision of democracy prepares us to interact with our world and guide it to a better future by immersing us in what he calls the method of critical intelligence”

Notably, Dewey sees democracy as a process rather than an end state: “democracy is not participation by an inchoate public, nor is it a perfected end-state to be attainted. It is the development of critical intelligence and a method of living with regard to the past, present, and future.”

Dewey urges us to consider ourselves as connected, interdependent beings. Connected and dependent not only on those who care for us as children, but broadly connected and dependent our past and present societies. Our individual selves are shaped by collective history and defined by innumerable interactions, and we each have a role to play in affecting the current lives of others and shaping the future contours of society.

As McKenna explains:

Our social situation is not something that simply happens to us, however. We appropriate and integrate our environment into experience. Whatever our situation, we participate in its future development. It does not develop separately from us. Our activity partially defines our social situation, and our social situation goes a long way to guiding our activity. There is an interplay of the determinant and indeterminate by which we realize the potential of the future. We are a perspective, influenced by our experience, through which we organize our participation and structure the community so that future experience is meaningful to us.

We create ourselves from our environment, and we create our environment through our selves.

This places a great responsibility on each of us to work for utopia. We must constantly and critically examine ourselves and our world, imagining better possible futures, and actively working towards and adjusting these visions.

We must each, as Dewey writes, learn to be human.

There is something compellingly beautiful about this vision; about the idea of a society which seamlessly integrates the individual and the whole, the past and the future. A society in which we all see ourselves as intrinsically interconnected and interdependent, working together to perfect ourselves, each other, and our shared experience.

Yet, perhaps this is far too much to hope for. The biggest complain about Dewey, most notably from Walter Lippmann, is that this vision is too unrealistic, too naive about the biases of people and the abuses of power.

As McKenna herself writes:

Even if the process model can prepare people to be the critical citizens it needs (a huge task in itself), how can it ensure that they actually will participate and take on their responsibilities? The process model asks a great deal of people in terms of time and effort. Apathetic or lazy citizens will not take up the critical stance easily. Where the end-state vision does not ask enough of people, or give enough responsibility to them, the process model may ask and give too much.

But, McKenna for one, finds reason to hope:

While the process model may require more of people than we are prepared to give now, visions on this model can provide us with insight into the means available to change our attitudes and action and show us the possibilities of the future if we are willing to try to change and become Dewey’s integrated individual…Utopia visions are visions of hope that can challenge us to explore a range of possible human conditions…the first step in understanding the responsibility each of us has to the future in deciding how to live our lives now.

For those less inclined towards hope, perhaps one can at least find some grim humor in this concluding note from McKenna’s final chapter:

One can hope that here, in the United States, the elections of 2000 have awakened people to the importance of their responsible participation in the political process.

The process model asks a lot, indeed.

A Story of Bridging Partisan Divides in the Legislature

A major goal of NCDD2016 is to lift up stories of how people across the country are Bridging Our Divides through D&D work, despite pervasive narratives telling us we can’t. So we wanted to share just such a story that NCDD member Jessica Weaver of the Public Conversations Project recently wrote about. The piece tells the story of women legislators who are resisting the urge to focus on the negative and instead look to solutions. You can read the story below or find Jessica’s original post here.

Shining a Light Beyond Polarization

We’ve all seen the headlines. Gridlock. Paralysis. Incivility. All the result of widening political polarization in the United States government, and also among its people. Like other aspects of identity, political ideology can be a dividing factor in our national conversation. We refuse to engage with the “other side” and reflect critically on our own views.

We’ve all seen the headlines. Gridlock. Paralysis. Incivility. All the result of widening political polarization in the United States government, and also among its people. Like other aspects of identity, political ideology can be a dividing factor in our national conversation. We refuse to engage with the “other side” and reflect critically on our own views.

The science shows that polarization has indeed worsened – almost exponentially – over the last ten years. Pew Research also indicates that in addition to estrangement, this trend has seen increased venom and antipathy between liberals and conservatives. There’s evidence that this trend is worsening, and that it has had profoundly destructive effects on American governance and its public discourse. We know that story.

But at a women’s leadership conference a couple of weeks ago, I heard a very different story. Women from all levels of government – senators, state legislators, and city council members – came together to talk about their experiences, challenges, and lessons from careers spent proving they were worthy of hard-earned entry into a sector dominated by men. In addition to stressing the importance of building personal relationships across the aisle to operate effectively, several legislators had a surprising response to the inevitable question about the seemingly irreversible tides of polarization and incivility.

Image via Politico

Instead of bemoaning how partisan bickering had stymied their work, Senator Barbara Mikulski (pictured center above) was almost indignant. “That’s not the whole story,” she said, and argued that in fact this had been one of the most productive years for women in the Senate that she could remember. And she would know: Mikulski started a monthly bipartisan dinner group just for female senators that encourages relationships between women across the aisle, and creates mentorship opportunities between generations of politicians.

The exchange made me think about something we talk about often at Public Conversations: the danger of focusing solely on conflict, especially in binary terms. By rehearsing the narrative of polarization, we are at one level simply making reference to a political reality, but at another, are pushing a wheel over the same groove, in jeopardy of deepening the schism. The story is self-fulfilling, according to recent research out of University of California – Berkeley, titled “Self-Fulfilling Misperceptions of Public Polarization,” which concluded that citizens across the political spectrum perceive one another’s views as being more extreme than they really are:

“Thus, citizens appear to consider peers’ positions within public debate when forming their own opinions and adopt slightly more extreme positions as a consequence.” In other words, being inundated with information about polarization doesn’t make us more moderate, it makes us more extreme.

This is a difficult position: how can we acknowledge the realities of deep conflicts without reinforcing narratives that are devoid of anything else? The question isn’t just relevant for polarization or other identity-based conflicts; it’s a question about how to discuss humanity’s most destructive creations – hate, bigotry, fear – without letting negativity define the whole story. I think an important answer lies in choosing to “shine a light on the good and the beautiful,” in the elegant language of writer and Muslim thinker Omid Safi. He writes, “Why shine the spotlight on the hate? This is somehow part of our national discourse. Someone does something offensive and crazy, and we immediately advertise it. But I do wonder about the mindset of always being quick to rush to publicize bigotry against us — and forget about the many who rise to connect their humanity with ours.” He ends his reflection by naming specific people whose work he wants to “shine a light on.”

So, Senator Mikulski and your dinner companions, I want to shine a light on you. Perhaps more importantly, I want to shine more lights in this often black or white world. This isn’t a call to end conversations that are challenging, simply to make space for celebrating good work that is of equal importance in the stories we tell. As Safi concludes:

So, friends, let us stand next to one another, shoulder to shoulder, mirroring the good and the beautiful. Shine a light on the good. Applaud the good. Become an advocate of the good and the beautiful. Let us hang on to the faith that ultimately light overcomes darkness, and love conquers hate. It is the only thing that ever has, ever will, and does today.

You can find the original version of this Public Conversations Project piece at www.publicconversations.org/blog/shining-light-beyond-polarization