“What’s the big idea?” Hepburn Shire Council’s Plan

Everyday Democracy: racism, policing, and community change

At this moment, I am especially grateful to serve on the board for Everyday Democracy, which works at the intersection of deliberative democracy, community organizing, and anti-racism. The organization has deep experience with “dialogue and action” efforts that “address community-police relations.” They bring explicit attention to racial injustice and are skilled at engaging police in conversations and reforms. This is an entry page to their relevant work. As we learned at yesterday’s board meeting, additional valuable resources and events are in development, so stay tuned to www.everyday-democracy.org, @EvDem on Twitter, and EverydayDemocracy on Facebook.

At this moment, I am especially grateful to serve on the board for Everyday Democracy, which works at the intersection of deliberative democracy, community organizing, and anti-racism. The organization has deep experience with “dialogue and action” efforts that “address community-police relations.” They bring explicit attention to racial injustice and are skilled at engaging police in conversations and reforms. This is an entry page to their relevant work. As we learned at yesterday’s board meeting, additional valuable resources and events are in development, so stay tuned to www.everyday-democracy.org, @EvDem on Twitter, and EverydayDemocracy on Facebook.

Unfavorable Candidates

“Lock her up” – a chant referring to presumptive Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton – has been called the unofficial slogan of the Republican National Convention. When I first heard the crowd break into this cheer, my immediate reaction was that it went too far. Disagree with your opponent, say they have the wrong vision, but…calling for their imprisonment? That is a disrespect that goes too far.

But, of course, that reaction reveals my own partisan biases. Would I have been so scandalized if something similar had happened at the 2004 Democratic Convention? Accusing then-President George W. Bush of war crimes? And of course, we don’t even know what is in store for next week’s Democratic National Convention. I’m sure they’ll have some disparaging remarks of their own.

The primary difference is perhaps whose remarks I happen to agree with.

As I thought about this more, it really struck me how notable it is that both party’s candidates have the highest unfavorables of any nominee in the last 10 presidential election cycles. That will have a dramatic effect on our post-election nation regardless of who wins. Secretary Clinton is “strongly disliked” by just shy of 40% of the electorate, slightly outpacing President George W. Bush’s 2004 numbers. Trump’s average “strongly unfavorable” rating goes even higher, at 53 percent.

If Secretary Clinton wins the general election, some significant portion of the population will think she should be locked up for acts one conservative paper has described as bordering on treason. If Trump wins, a significant portion of people will believe we’ve handed the nuclear launch codes to an egotistical, xenophobic blowhard who values nothing but his own prestige.

Either way, it’s bad for democratic engagement.

Send Best Rakhi Puja Thali Online to Elate Your Brother this Raksha Bandhan

My Latest Essay – on the Intentional Costs of Comfort

Published in the 'Southwestern Philosophy Review,' 31, Issue 1, 2016, 19-24.

Hi folks.  It’s been quite a while since I’ve posted. There’s a reason that they say moving is one of the most stressful times in life. It certainly is. Among the many things I’ve been meaning to post is my latest essay, which is a commentary piece I wrote and originally delivered at the 2015 meeting of the Southwestern Philosophical Society conference. The society met in Nashville, TN, at Vanderbilt University. That doesn’t sound very Southwestern, admittedly, but it’s a great group. The essay was a response to the keynote address by Dr. John Lachs of Vanderbilt. It was an honor to comment on his talk, “The Costs of Comfort.” John has been a mentor of mine for close to 20 years. As you’ll see in my commentary essay, however, that doesn’t mean that I went easy on his argument.

It’s been quite a while since I’ve posted. There’s a reason that they say moving is one of the most stressful times in life. It certainly is. Among the many things I’ve been meaning to post is my latest essay, which is a commentary piece I wrote and originally delivered at the 2015 meeting of the Southwestern Philosophical Society conference. The society met in Nashville, TN, at Vanderbilt University. That doesn’t sound very Southwestern, admittedly, but it’s a great group. The essay was a response to the keynote address by Dr. John Lachs of Vanderbilt. It was an honor to comment on his talk, “The Costs of Comfort.” John has been a mentor of mine for close to 20 years. As you’ll see in my commentary essay, however, that doesn’t mean that I went easy on his argument.

In philosophy, we say that “criticism is the fondest form of flattery.” The idea is that engaging in argument with someone’s ideas isn’t a bad thing. It’s joining in with the author in the pursuit of the truth. The honor is in taking someone’s ideas seriously, thinking hard with him or her, or them, and about something of importance attended to in the piece. In this essay, I respond to Lachs’s arguments about “The Costs of Comfort.” It’s a work in progress, though the version I reply to was also published, with my response to it. The costs of comfort are significant, Lachs argues, and some of what “reformers” want to change about present problems can amount to an unwillingness to accept the costs of living the comfortable lives so many of us enjoy today. We may bemoan environmental degradation, but summers in Mississippi are brutal enough even with air conditioning.

About many examples, Lachs is quite right and reasonable, but there are, I argue, avoidable costs of comfort. There are also costs of comfort that are not only accidental, but actually intentionally targeted towards people who are thereby disadvantaged. Racism and other forms of cultural violence lead all kinds of costs of our comfort to be put upon groups made to suffer their weight. In my essay, I defend the need for “reformers,” not for the basic costs of comfort, but for the many troubling cases. Many people reasonably feel for animals and I certainly agree that factory farming needs reform, but when the bugs start to get into my house or my bed, I feel no remorse for hiring the exterminator to keep certain levels of comfort at the expense of bed bugs.

That said, injustice is not some simple thing to sacrifice to beat the heat or to keep the bugs out. If we can significantly reduce air conditioning costs with white roofs instead of black ones, furthermore, shouldn’t policy encourage such reforms? If we can raise chickens in far more humane ways than in the cages that are so troubling, why not endure the small discomfort it takes to make that change? Reform can overreach and be unrealistic, but it can also be absolutely vital for good people to sleep at night.

It’s easy for the most comfortable among us to focus on the simpler examples than injustice. Yes we like our comforts, but in time, so many innovations can at least reduce the costs we cause, and still other costs are simply unjustifiable.

If you want to check out my essay, which is a lot more specific than this quick post, visit my Academia.edu page with the piece.

If you’re interested in a speaker for your event, visit my speaking and contact pages. You can also “like” my Facebook author page and follow me on Twitter @EricTWeber.

How Elite and Popular Discourse Supress Dialogue

We are happy to share the announcement below about a new facilitation training opportunity in California from NCDD supporting member Donald Ellis from the University of Hartford. Donald shared this piece via our great Submit-to-Blog Form. Do you have news or thoughts you want to share with the NCDD network? Just click here to submit your news post for the NCDD Blog!

Me Talk Prettier Than You: Elite and Popular Discourse

One of the divides that has emerged more starkly from the Brexit debate and the candidacy of Donald Trump is the distinction between elite and popular discourse. Just being overly general for the moment, elite discourse is most associated with the educated and professional classes and is characterized by what is considered to be acceptable forms of argument, the use of evidence, the recognition of complexity, and articulation. Popular discourse is more ethnopolitical and nationalistic. It is typically characterized by binary thinking, a simpler and more reductive understanding of the issue, and an ample amount of cognitive rigidity makes it difficult to change attitudes. To be sure, this is a general characterization because both genres are capable of each.

Still, consistent with the well-known polarization of society is the withdrawal of each side into a comfortable discourse structure where the two codes are increasingly removed from one another and the gap between them cannot be transcended very easily. Dialogue is a real challenge if possible at all.

Additionally, elite and popular discourses share some different sociological and economic orientations. Elites are more cosmopolitan and popular is more local and nationalistic. Elites live in more urban centers and are comfortable with and exposed regularly to diversity. Those who employ more popular discourse tend to live in smaller towns and are more provincial. They seem to resist cultural change more and are less comfortable with diversity.

These two orientations toward language divide the leave-remain vote over Brexit and the electorate that characterizes the differences between Clinton and Trump. But this distinction is more than a socioeconomic divide that reflects some typical differences between people. It symbolizes the polarization currently characterizing American politics and has the potential to spiral into dangerous violence as the “popular” form of discourse becomes more “nationalistic.” It lowers the quality of public discourse and typically degenerates into even more rigid differences and stereotypical exemplars of elite and popular discourse. Nationalist discourse substitutes close minded combativeness for elite debate which can be passionate but is geared toward deliberative conversation that can be constructive. Nationalism is the deep sense of commitment a group has to their collective including territory, history and language. When national “consciousness” sets in then one nation is exalted and considered sacred and worthy of protection even in the face of death. Trump’s catchphrase “make America great again” or “let’s take our country back” or his appeals to separation and distinctiveness by building walls that clearly demark “us” and “them” are all examples of a nationalist consciousness that glorifies the state.

The nationalism espoused by Trump and the “leave” camp during Britain’s vote on the EU question are the primary impediments to consolidating, integrating, and strengthening democracies. All states with any sort of diverse population must establish a civil order that protects those populations; that is, no society will remain integrated and coherent if it does not accommodate ethnic diversity. At the moment, Trump’s rhetoric is divisive and representative of a tribal mentality that clearly wants to separate in many ways various communities in the US. Trump’s references to Mexicans, Jews, Muslims, for example betrays his own nationalistic sentiments.

The two ways to handle ethnic diversity are either pluralistic integration or organizational isolation of groups. Isolating and separating groups is inherently destabilizing and foment ripe conditions for violence. Building a wall and making determinations about who can enter the United States and who can’t are all examples of isolating groups. Intensifying nationalist discourse and the privileging of rights for a dominant group is fundamentally unsustainable.

This gap in the United States between an elite discourse and the nationalist discourse has grown wider and deeper. Each side snickers at the other’s orientation toward language and communication and continues the cycle by reinforcing the superiority of his own discursive position.

Lost Things

Sometimes,

I’ll spot an abandoned shoe by the side of the road.

Perhaps a pair of shoes.

Out in the middle of nowhere.

I wonder where they came from.

In the winter,

There are gloves and hats and scarves.

Hanging daintily from a fence post.

Perhaps their owners will find them.

I’ve seen pacifiers and well-loved toys.

Somewhere a child is screaming,

But I WANT it.

Sorry, kid.

It’s gone.

Until you happen upon it again,

Or someone else claims it as their own.

Or perhaps it makes it’s way

to some giant trash pile.

The final resting place of forgotten things.

Lessons in Listening to Students from Providence Youth

We recently came across a piece on a student-led, World Cafe-style event in Providence that provides a wonderful example of how schools can bridge the divide between youth and adults and teach deliberation, and we had to share it. The article below by Megan Harrington of the Students at the Center Hub describes the event, the students’ discussions, and their proposed solutions to issues in their schools, most of which are summarized in the open letter the students wrote after the event. We hope to see more processes engaging young people like this nationwide! You can read Megan’s piece below or find the original here.

#RealTalk: Providence Students Raise Their Voices

On a sunny Wednesday afternoon in April, over 100 high school students gathered at the Providence Career and Technical Academy cafeteria, talking with friends, setting up tables with sheets of paper and markers, and manning sign-in tables. They were members of the Providence Youth Caucus (PYC) – a coalition of Providence’s seven youth organizations -gathering to develop solutions to improve education in their public schools, which they would then share with relevant policymakers to advocate for change.

An entirely student-led event, the PYC Superintendent’s Forum began a little after 4pm, when student speakers took the microphone at the front of the room to lay the groundwork for the event. “Your thoughts and voices matter,” they said. “We’re going to take all of your ideas and present this data to the superintendent and city officials so we can make a difference.”

Key school leaders – including Providence Public Schools Superintendent Chris Maher – attended the event to hear the students’ insights.

After a round of icebreakers, the students quickly broke out into nine tables to discuss hot topics in education such as personalized learning, school culture, discipline, student voice, and the arts. Two facilitators – a conversation leader and a note-taker – led the discussions at each table, while the other participants rotated to a new topic table every 10 minutes.

The first table I sat down with discussed the value of arts education, the strengths and weaknesses of Providence high school art programs, and what an ideal arts education would look like.

Most students at the table felt arts programs were critical for students to develop new skills, express themselves creatively, and explore possible career paths. One student excitedly shared his experience in his school’s engaging graphic design class, but most students felt their schools’ arts programs were lacking or even for show. One young woman said she took a calligraphy class that lacked necessary pens and ink until a month into the semester, but “it was an arts class, so it counted.” Some students lamented that art studios were eliminated to make space for engineering labs, or arts funding was cut to continue funding sports. And, others commented, because higher standardized test scores meant more school funding in general, arts programs were often cut in favor of those courses that incorporated standardized testing. Overall, students seemed to be in agreement – improved arts programs were necessary at their schools.

At a neighboring table, students contested the importance of student voice in the classroom.

Most students agreed student voice was not being adequately heard in their schools. “If it was being heard, many of these changes would have already been made,” one young woman reasoned.

But why wasn’t student voice being heard? Some said the burden was on students. “We should make more of an effort to speak up, organize in our schools, and discuss these issues with our principals,” one young man commented. “But there are some students who are speaking up but aren’t being heard,” said another. Others in the group agreed. Veteran teachers were unaccustomed to incorporating student voice and made students feel like the classroom dynamic was adversarial. “Even student government can’t go in front of school leaders and be taken seriously,” one student chimed in.

And where did students feel their voice was most lacking? Curriculum issues struck a chord with many, leading to an animated discussion about non-white history. “The last time I heard about slavery was in 6th grade; all I’ve learned about since then are the ‘World Wars,’” noted one young woman. “Black History Month is the only time I learn about black history,” chimed in another student. Others expressed their frustration with the focus on European history: “Why can’t we have an AP African History or an AP South American History?” one student questioned. In contemplating solutions to this important issue, the Providence students concluded that it was important to have a diverse teaching staff to bring varying perspectives to history.

After students had visited a number of tables, the team facilitators shared the ideas collected over the hour with entire conference. Everyone cheered after each presentation, giving extra applause when they felt particularly inspired.

Like many of the students that night, I left feeling invigorated and inspired, excited to see where their discussion would lead in the future. The Providence Youth Caucus is scheduled to formally present their data from the Forum to the district’s school board and Superintendent Maher on July 27, 2016. Stay tuned for the results of their presentation!

Providence Youth Caucus is comprised of seven Providence student groups – Hope High Optimized (H2O), New Urban Arts, Providence Student Union, Rhode Island Urban Debate League, Youth in Action, YouthBuild Providence, and Young Voices. Learn more about their efforts by following them on Twitter at @pvdyouthcaucus.

You can find the original version of the above piece from Students at the Center Hub’s blog at www.studentsatthecenterhub.org/realtalk-providence-students-raise-their-voices.

what is the political economy that people are revolting against?

(Hartford, CT) One interpretation of Trump, Brexit, and related phenomena is that people fear losing their privileges and are reacting with prejudice against immigrants and racial and religious minorities. That thesis must contain a lot of truth. But a different–and compatible–interpretation is that large elements of the working class are revolting against an unjust but dominant political economy.

For instance, Harvard Professor Richard Tuck makes the leftist case for Brexit. Britain needed to leave the EU because “the essence of the EU is neoliberal. … The policies that are enshrined in its treaties and in its administrative structures are essentially those of the neoliberals.” Meanwhile, in the US, Trump holds a double-digit lead over Clinton among the working class as a whole, while he trails by similar margins among college-educated people–and the US Chamber of Commerce denounces his position on trade.

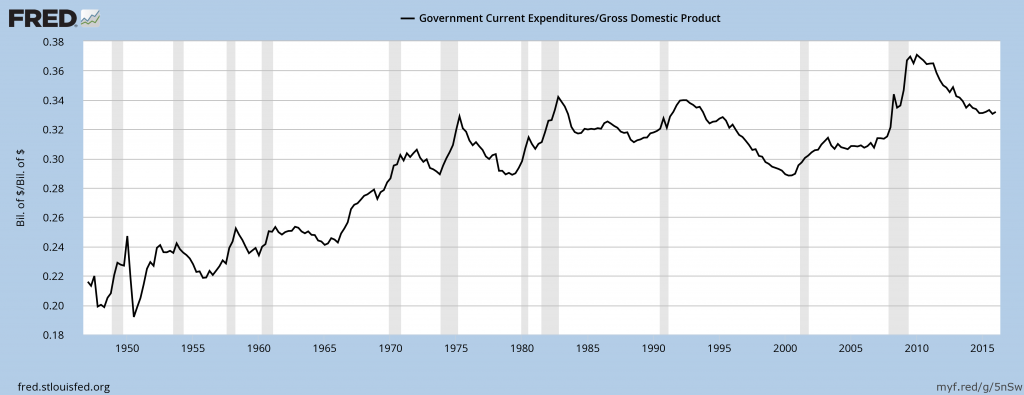

If the working class is rising up, what are they rising against? Hardly anyone calls himself a “neoliberal,” and critics load a lot of diverse ideas into that term. It presumably doesn’t mean libertarianism or laissez-faire, because then we could just use those words (dropping the “neo-“). What’s more, the US and EU have not moved in a libertarian direction. Here, for instance, is the trend in government spending as a percentage of GDP in the USA. It’s basically up, albeit with declines in the last six years of both the Clinton and Obama administrations.

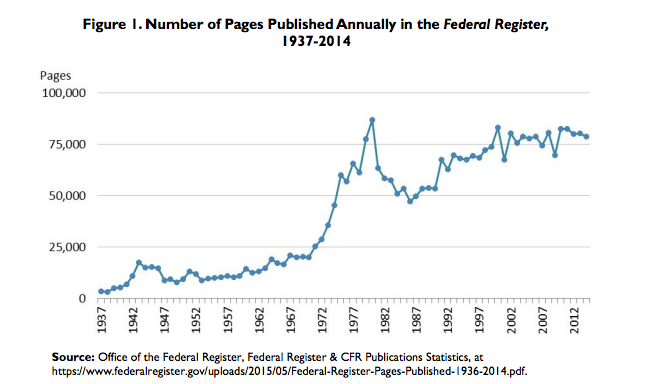

The volume of government regulation is also up, although that’s harder to measure. This is the size of the annual federal compendium of new regulations, measured in pages. A libertarian regime would not issue 80,000 pages of new rules per year.

There are many good things about regimes like the US and the EU member states. In broad, historical context, they are relatively free, prosperous, safe, and democratic. Nevertheless, I will emphasize the negatives, for much the same reason that your doctor wants to talk about your hypertension and family history of cancer, not how wonderfully well your liver and kidneys are working. In other words, I’ll offer a critical assessment even though there would also be many positive to points to make.

In brief, I think that states are increasingly powerful, but they are accountable to capital, not to citizens. That’s what critics mean by “neoliberalism,” although “state corporatism” might be a better phrase. I’ll break the diagnosis into six parts.

1. Deindustrialization

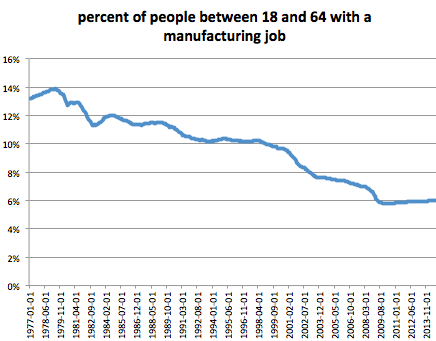

We call the wealthiest countries of the world the “industrialized” nations, but that description is becoming obsolete. These countries did industrialize after 1800 but have shed most of their manufacturing jobs. Below is the trend for the US since 1977. The graph understates the decline, because many more than 14% of households had at least one manufacturing worker, usually a man, in 1978. Also, the rate was higher in 1950, but I can’t find a longer time series. In any case, the decline since 1977 has been steep.

Manufacturing jobs are rarely enviable, but they give their workers political leverage because they require expensive, fixed investments. Ford’s River Rouge plant in Detroit employed 100,000 men at its peak (versus 6,000 people today). Autoworkers could organize and strike. They voted in city and state elections. It was expensive for Ford to move its investments out of Detroit, although that gradually happened, and the city has lost 61% of its population. But in the heyday of industrialization, Ford needed those men to be reasonably happy. In return, manufacturing workers benefitted from their political leverage–including Black workers, whose civil rights improved with their concentrated market power in factories.

By contrast, Google, which is worth about half a trillion dollars, employs some 50,000 people, worldwide. They are well paid, but they remain at Google for a median of 1.1 years. They have market value–far above the average market value of average Americans, let alone average human beings–but they have little or no political leverage. Even the best-paid are dispersed, transient, and eminently replaceable.

2. Mobile capital

The fact that you can now make more money by investing in intellectual property and networks rather than rooted industries is one reason that capital moves faster than ever before. Capital mobility is also encouraged by favorable laws and treaties and by financial instruments, analytics, and other tools that assist investors.

The result is a substantial increase in the leverage of capital even as the leverage of labor has weakened. Businesses gain their “privileged position“–even in democracies with free and fair elections–from two major sources. First, since a business is organized, it can deliberately advocate for its interests by lobbying or advertising, whereas diffuse interests (like consumers or workers) have much more trouble acting politically. Second, investments are essential for prosperity, and a business can move its investments. Thus, even without lobbying at all, a business–or an individual investor–gains leverage over governments. Its ability to invest and or disinvest gives it power. That power has rapidly increased. It also reinforces …

3. Deference to wealth

This point is harder to quantify, but I perceive that we live at a time when billionaires, celebrities, and CEOs are given extraordinary deference, especially in comparison to run-of-the-mill elected officials, civil servants, union leaders, and grassroots organizers. Politicians, for instance, are constantly in contact with their wealthiest constituents. First-year Democratic Members of the House are advised to spend four hours per day of every day calling donors. Meanwhile, many advocacy groups are funded by rich individuals, not sustained by membership dues, so their leaders are also constantly on the phone or at conferences and meetings with wealthy people. The conversations in these settings tend to be deeply deferential, and they occur behind closed doors. Of course, these habits are abetted by laws and policies–especially, laws governing campaign finance in the US. But we observe somewhat similar deference in other countries with better laws. I think the deeper cause is the shift of leverage to economic elites.

4. The market colonizes the public sphere

“Commonwealth” is a translation of “republic,” which could be more literally rendered as “the public’s thing.” In a republic, the government is supposed to be distinct from the private sector. As the custodian of the common wealth, it operates on different principles from a market. These principles are not simply majoritarian, for the commonwealth belongs to our unborn children as well to us. We have no right to waste it by voting for the wrong policies. A republic strives to define and implement something worthy of the title “public good.”

That distinct ethic has been lost, as governments are almost universally seen simply as service-providers, constantly compared to businesses on the grounds of efficiency, and expected to compete in a market for popularity and influence. In a 1870 case, the Supreme Court declared a lobbyist’s contract void on the ground that it would be “steeped in corruption” and “infamous” for any business to hire someone “to procure the passage of a general law with a view to the promotion of their private interests.” The Court added:

The foundation of a republic is the virtue of its citizens. They are at once sovereigns and subjects. As the foundation is undermined, the structure is weakened. When it is destroyed, the fabric must fall. Such is the voice of universal history. The theory of our government is that all public stations are trusts, and that those clothed with them are to be animated in the discharge of their duties solely by considerations of right, justice, and the public good.

We certainly didn’t live up to those words in 1870s, when government was in many ways more corrupt than it is now. But the animating philosophy of a public good was still alive then. In contrast, Buckley v Valeo (1976) defines political money as constitutionally protected speech, and Citizens United (2010) equates businesses with civic associations. These are examples of a general erosion of a distinction between public good and private interests.

5. States have increasing power

If we lived in a neo-“liberal” or laissez-faire era, states would be constrained. In some ways, they are, but they also have more access to data about people than ever before; they have an easier time surveilling, influencing, punishing, and even killing individuals; and they operate increasingly powerful systems for enforcing discipline, headlined by the vast prison system of the USA. Their ability to see, count, and act also extends far beyond their borders, making people in most parts of the world subject to more than one government at once.

6. But states need their citizens less

On the other hand, states don’t need their own citizens. They don’t need us as military conscripts, because they can fight using small numbers of highly equipped experts, and they don’t need most of us as taxpayers, because they can finance their operations on international markets.

Mitt Romney did himself no favors by accusing 53% of Americans of being “takers” instead of “makers.” (Also, his numbers were off, since he omitted people who pay payroll taxes.) But he was right that a small minority can finance a modern government, which means that the state really doesn’t have to pay much attention to the rest of its people.

Put those six premises together, and you would predict a political regime in which investors use an expansive and intrusive state to promote their own interests. This seems almost precisely accurate as a description of regime like China’s, and all too apt when applied to the US, the UK, or the EU as well. It doesn’t excuse voting for Donald Trump, who offers no alternative and threatens fundamental rights. I don’t think it offers a very good rationale for Brexit, either. But it does explain why a political class wedded to this status quo would face an electoral insurrection.