state policies for civics: it’s all about implementation

Just published: Peter Levine & Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, “State Policies for Civic Education,” in Esther Thorson, Mitchell S. McKinney, and Dhavan Shah, eds., Political Socialization in a Media-Saturated World (New York: Peter Lang, 2016), pp. 113-24.

Abstract: Several large cross-sectional surveys confirm the same patterns: high-quality forms of school-based civic education (such as moderated discussion of controversial current topics) are related to students’ civic knowledge and engagement, but state policies that mandate various forms of civics are not related to civic knowledge or engagement for their young adult populations. We explore the possibilities that: 1) the existing state policies are not satisfactory, 2) state policies cannot reliably influence educational practices, or 3) support for implementation is essential.

I think the last point is most important, and that’s why we have been working closely with Florida Partnership for Civic Learning and the Illinois Civic Mission Coalition to support local stakeholders (district leaders, academics and teacher educators, nonprofits, and state officials) to implement their respective states’ policies for k12 civics. A good law may be necessary, but it is insufficient without continuous attention to implementation: producing a good test every year, supporting current and future civics teachers, selecting and recommending materials, analyzing data from tests, surveys, and interviews to learn what’s working, and using the resulting insights to improve standards, tests, materials, and professional development–in a continuous cycle.

Two NCDD Members Share IAP2 USA Research Award

We are proud to share that two of our great NCDD members – Kyle Bozentko of the Jefferson Center and Tina Nabatchi of the Maxwell School at Syracuse – have been jointly awarded the Research Project of the Year Award by NCDD member organization IAP2 USA.

The award came as part of the US branch of the International Association for Public Participation‘s annual Core Values Awards, which it gives to outstanding organizations or projects that represent the best of the best in public participation.

The award came as part of the US branch of the International Association for Public Participation‘s annual Core Values Awards, which it gives to outstanding organizations or projects that represent the best of the best in public participation.

Kyle and Tina’s project was called “Clearing the Error: Public Deliberation about Diagnostic Error,” and it used the Citizen Jury process to involve everyday medical patients in improving their common problems with health diagnoses. It was an innovative use of deliberation to really empower people to make an impact on a key issue in health care systems, and we congratulate them on a job well done!

You can learn more about the award-winning “Clearing the Error” project in the video below:

There is more info on Kyle and Tina’s project as well as all the other award winners at www.iap2usa.org/2016cva. But for now, please join us in congratulating Kyle, Tina, and their teams on winning this important award!

The State of Public Voice, Post-Election

Why Let the People Decide?

Indigenous Management System (IMS) – Insights from the Ethiopian Qero Management System

New Assessment Items for Florida Civics Teachers!

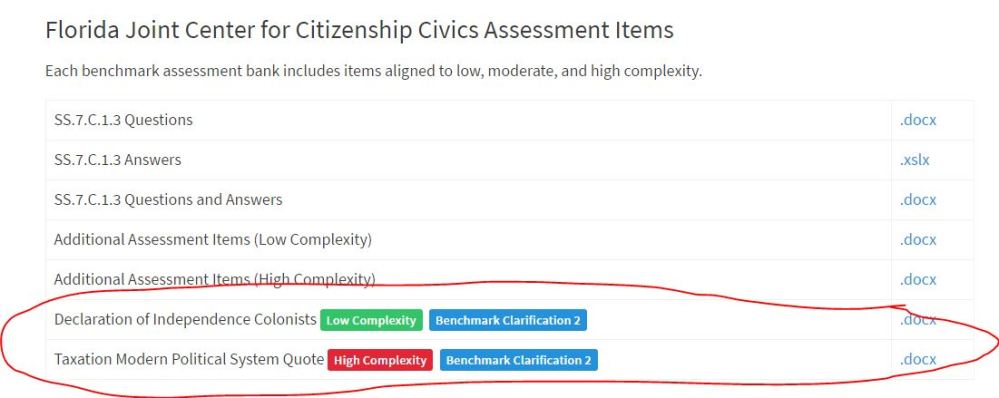

The Florida Joint Center for Citizenship is pleased to announce that we have completed another round of item development and review! Thanks to our own Dr. Terri Fine for her hard work on getting these done, and our Mike Barnhardt for getting them up on the main site. You can find these new items on our main site at Florida Citizen. Simply hover over the ‘Resources’ link, visit the 7th Grade Applied Civics page, and scroll down to the benchmark you want to play with! Once there, scroll to ‘Civics Assessment Items’ and you will see the new ones! Note that we have a new format for upload. To make it easier for you, we have identified the type of stimulus or content, the complexity, and the benchmark clarification. A list of all new items is below. If you have questions, please feel free to email me!

Standard 1 Items

1-1_BC3_L Montesquieu Government Characteristics

1-2_BC1_H Bhutan English Bill of Rights Quote

1-3_BC2_L Declaration of Independence Colonists

1-3_BC2_H Taxation Modern Political System Quote

1-4_BC2_L Prince Tyrant Quote

1-4_BC2_H Prince Tyrant Modern System Quote

1-4_BC2_M Locke Declaration of Independence Quote

1-5_BC1_L Articles of Confederation Structure

1-5_BC1_H Constitutional Amendment Quote

1-6_BC1_M Including Preamble Constitution Quote

1-6_BC1_H Government and the People Quote

1-6_BC1_L Constitutional Goals and Purposes

1-7_BC1_BC4_H Federalist 51 and Constitutional Government Quote

1-7_ BC4_M Checks and Balances Scenario

1-7_BC2_L Describe Checks and Balances

1-8_BC3_M Anti-Federalist Paper Brutus Quote

1-8_BC1_L Documents about Proposed Bill of Rights

1-8_BC1_H Federalist 47 and Supreme Court Quote

1-9_BC1_L Political System Characteristics

1-9_BC2_BC 3_M Nixon Constitution Quote

Standard 2 Items

2-1_BC3_H Employment Long Term Impact Graph

2-2_BC 1_L Citizen Obligation Scenario

2-2 BC2 M_Civic Responsibility Common Good

2-2 BC2_M Pay Taxes

2-2_BC2_M Ballot Box Image

2-2_BC3_L_Citizens State Government

2-2_BC3_L_Citizens Local Government

2-2_BC3_L_Citizens Federal Government

2-2_BC3_M Armed Forces Image

2-2_BC4_H Running for President Headline

2-2_BC_6 Jury Duty

2-2_BC7_M Selective Service Image

2-4_BC4_M Rights of Accused Scenario

2-5_BC2_M Socialist Party Constitutional Principle Quote

2-5_BC2_BC3_H Socialist Party Supreme Court Decision Scenario

2-8_BC1_L Party Platform Individual Rights Quote

2-9_BC2_M Florida Two Term Governor

2-10_BC1 BC4_H Lobbyists Cartoon

2-10_BC3_BC4_H Lobbyists Impact on Government Quote

2-11_BC1_H Presidential Candidate Issue Support Image

2-11_BC1_L Symbols

2-12_BC1_L_SP2 Trash Collection

2-12_BC1_L_SP1 Trash Collection Level of Government

2-12_BC1_M Relationships Between Counties Scenario

2-12_BC2_M State Agency Student Testing Scenario

2-13_BC 1_M Public Perspectives Immigration

2-13_BC1_M Perspectives on Minimum Wage

2-13_BC3_H Immigration Graphic

Standard 3 Items

3-1_BC3_H Corrupt National Leaders Scenario

3-2_BC4_H1 Parliamentary Elections Headline

3-2_BC4_H2 President and Congress Quote

3-3_BC2 President and Supreme Court Quote

3-3_BC3_M House of Representatives Quote

3-4_BC4_H Constitutional Relationships Map

3-5_BC4_H Proposed Constitutional Amendment Headline

3-5_BC4_M Constitutional Amendment Process

3-6_BC1_M Civil Rights Movement

3-6_BC3_L Violation of Constitution Scenario

3-7_BC2_BC3_M 26th Amendment

3-7_BC3_H Poll Tax Image

3-7_ BC3_ M Political Participation Graph

3-7_BC3_L Ratification of Voting Rights Amendments

3-7_BC3_M Amendments Right to Vote

3-8_H Cabinet Nominations Headline

3-11_BC1_L Court Jurisdiction

3-11_BC1_H US Supreme Court Citizen Rights Quote

3-12_BC 1_M Gideon v Wainwright Quotes

3-12_BC 1_M DC v Heller Quotes

3-12_BC3_L United States v Nixon

3-12_BC 1_M Bush v Gore Quotes

3-12_BC 1_M Tinker v Des Moines Quotes

3-13_BC1_L US Constitution-Rights

3-13_BC4_H Federal Constitution Powers Quote

3-13_BC4_M State-Federal Relationship Quote

3-14_BC1_L Government Services

3-14_BC2_H Government Services Quote

Standard 4 Items

4-1_BC1_L Domestic Policy Action

4-1_BC3_H Domestic Foreign Cartoon

4-1_BC4_M Secretary of State Quote

4-1_BC4_H US Domestic and Foreign Affairs Quote

4-1_BC 4_M Employment Cartoon

4-1_BC5_L Secretary of State

4-2_BC2_M1 UN Headquarters Quote

4-2_BC2_M2 International Organization Headquarters Scenario

4-3_BC1_L US Declare War on Japan

4-3_BC1_H President-Congress Relationship Quote

Facts, Bias, and Horse-Race Journalism

I’ve been thinking a lot this election season about an argument from Peter Levine’s We Are the One’s We’ve Been Waiting For.

What if, instead of horse-race journalism where pundits try to predict who will win, our media environment was governed by “public journalism” or “civic journalism” – with reporters asking who should win?

This question seems to fly in the face of common understandings of “good” journalism. Good journalism should be neutral, non-biased, and fact based. By tackling an inherently biased question such as “who should win,” a journalist cannot possibly meet appropriate ethical standards.

Yet, that’s not an entirely accurate take on the situation.

I love quoting Bent Flyvbjerg’s modified proverb: “power is knowledge” – that is, as Flyvbjerg argues, those with power define what counts as knowledge and fundamentally shape reality with their power.

In Rationality and Power, Flyvbjerg meticulously documents how power shapes knowledge throughout the planning process for a new transit hub in Aalborg. The initial list of proposed sites indicates one as most promising, numerous studies confirm the promise of that site and the problems with other sites. Yet – that “promising” site was, in fact, pre-selected by elites and all the research in which that option naturally rises to the top as the best choice is carefully, artfully curated to ensure that decision.

In Power and Powerlessness, John Gaventa similarly argues that power shapes reality – as people in power get to choose not only what issues are addressed, but also what issues are raised.

Both Flyvbjerg and Gaventa warn about the invisibility of this power – in the most insidious, entrenched power structures, this subtle shaping of what does and does not count as knowledge goes largely unnoticed. It’s just taken as a giving that the issues talked about, and the framing given to them, are the factual, non-biased ways to address them.

And this is what is so dangerous about horse-race politics. It’s presented as neutral, but in fact, it’s not neutral at all. Every decision about what does or does not become part of the conversation shapes the electoral atmosphere. There is no neutral coverage.

Levine provides an example of an alternative approach: in the early 1900s, the Charlotte Observer dispensed with “horse race campaign coverage, that is, stories about how the campaigns were trying to win the election. Instead, the Observer convened representative citizens to choose issues for reporters to investigate and to draft questions that the candidates were asked to answer on the pages of the newspaper.”

In this way, political coverage responds to the interests and priorities of “the people” writ large, without devolving into a mess where no knowledge is taken fact leaving only “mere opinion.”

They may be other, and possibility better, approaches as well.

All I know is that now – one week away from the end of the 2016 Presidential Election – after all the coverage, all the ads, all the sound and fury that has gone on for months…I find myself wishing we’d spent just a little more time not asking who will win, but really examining: who should win?

Fire and Frost: The Virtues of Treating Museums, Libraries and Archives as Commons

This piece by Michael Peter Edson, is part of our celebration of the online release of Patterns of Commoning, an anthology of essays about notable commons from around the world. Edson's essay was originally published in the book, edited by me and Silke Helfrich and now freely accessible at patternsofcommoning.org. All chapters are published under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license.

Edson is a strategist and thought leader at the forefront of digital transformation in the cultural sector. Formerly with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., Edson is now Associate Director/Head of Digital at United Nations Live Museum for Humanity, Copenhagen, Denmark. The opinions in this essay are his own.

By Michael Peter Edson

It was usually a note in the newspaper, a few pages back. Or, if the blaze was big enough and a camera crew arrived quickly, a feature on the evening news. It seems like house fires were more common when I was young, and the story was often the same: “As they escaped their burning home,” the newscaster would say, “they paused to save a single prized possession…” And it was always something sentimental – not jewelry or cash but a family photograph, a child’s drawing, a letter, a lock of hair. Ephemera by any measure, and yet as dear as life itself. Museums are simple places. Libraries and archives too. Collect, preserve, elucidate. Repeat forever. We don’t think about them until the smoke rises, but by then it’s usually too late.

When Hitler ordered the destruction of Warsaw in 1944, the army tried to set the national library – the Biblioteka Narodawa – on fire, but the flames smoldered.[1] It turns out that the collected memory of a civilization is surprisingly dense and hard to burn, so a special engineering team was brought in to cut chimneys in the roof and holes in the walls so the fire could get more air. Problem solved. Museums, libraries and archives are simple places, but once the flames take hold they burn like hell.

building grassroots power in and beyond the election

I’m speaking today at a Wellesley College event entitled “The People Take Over the Election: Building Grassroots Power in and Beyond the Election.” I think this will be my thesis: We must be organized to have power and to exercise it productively.

I’m speaking today at a Wellesley College event entitled “The People Take Over the Election: Building Grassroots Power in and Beyond the Election.” I think this will be my thesis: We must be organized to have power and to exercise it productively.

Only when you are organized can you seriously ask the question, “What should we do?” Without an organization, you can still ask, “What should I do?” but none of us can do all that much alone. We end up combatting climate change by changing our own lightbulbs, or addressing racism by trying to improve our private thoughts. These are not pointless strategies, but they are badly insufficient.

Without an organization, you can ask, “What should be done?” or “How should things be?” or “What should somebody else–often the government–do?” Those questions are too easy. (Carbon should be taxed; police should be overseen.) The hard part is figuring out how we can make those things happen. A habit of thinking only about what should be done encourages a spectator attitude toward politics.

People without organizations end up being represented by famous individuals–celebrities–who claim to speak for them and who claim mandates on the basis of their popularity. Celebrities have no incentives to address social problems; they gain their fame from their purely critical stance. And they owe no actual accountability to their fans, since no one (not even a passionate fan) expects a celebrity to deliver anything concrete. Donald Trump is unusual in that he has moved from a literal celebrity to a presidential nominee; but he still acts like a celebrity, and presumably he will return to being a pure mouthpiece once the election is over. Meanwhile, back at the grassroots level, a person who feels represented by celebrities is unlikely to talk productively with fellow citizens who disagree.

I mention Trump here because one important fact about his core constituency, White men without college degrees, is that they used to be organized, but that is no longer true. For instance, less than 6 percent of them are in unions. That’s an 80- or 90-percent decline* since the 1950s, and they are now less unionized than college grads are.

If you have no organizations behind you, you’ll typically feel powerless. If that’s how you feel, you are unlikely to want to participate in a difficult conversation, make sacrifices and tradeoffs, acknowledge any unfair advantages, or negotiate. Again, to use Trump voters as an example: they are overwhelmingly White, and it would be appropriate for them to acknowledge White privilege when issues of racial injustice arise. But I think they are very unlikely to acknowledge their own privilege, let alone agree to concessions, as long as their overwhelming experience is one of powerlessness. And I think they are powerless if they are unorganized and represented only by unaccountable celebrities. This implies, by the way, that one of the most important tasks confronting us today is organizing the White working class.

Organizations build what Charles Tilly named WUNC: worthiness, unity, numbers, and commitment. For instance, the protesters now holding ground at Standing Rock are demonstrating that they have a right to be there (worthiness), that they stand together (unity), that there are a lot of them, with a lot of supporters around the world (numbers), and that they are willing to face violence (commitment). WUNC is a scarce but renewable asset for social movements. Poor and marginalized people all over the world have build WUNC and used it to change the world.

It may be that we can do without older forms of organizations, such as unions, grassroots-based political parties, and religious congregations, now that we have digital networks. I think the jury is still out on that question. Loose, voluntary networks of activists brought down the Egyptian government, but once those networked activists confronted the organized Muslim Brotherhood, they lost the election, and once the Muslim Brotherhood confronted the even better organized Army, they lost a bloody struggle for survival.

We need organizations during an election. It might appear that when it’s time to vote, each person can exercise power individually and privately. But that power is actually pretty trivial. Nate Silver currently gives Hillary Clinton a 99.8% chance of winning Massachusetts, which means that each vote here is close to irrelevant. What matters in an election is not your individual vote but your participation in organized efforts to change the whole discussion, the balance of power, and the outcome.

Campaigns are such efforts. The Clinton campaign will spend more than half a billion dollars to build and run an organization. But modern presidential campaigns are problematic organizations because they rely so much on wealthy donors, they spend their cash so heavily on propaganda, and they establish short-lived transactional relationships with their own voters. But they are still organizations, and their power reinforces the importance of building other kinds of organizations as well.

*not percentage-point, by the way.