deliberation or simulated deliberation? choices for the classroom

In an article published today (“Deliberation or Simulated Deliberation?” in Democracy and Education, 26, 1, Article 7), I respond to a valuable previous piece by Margaret S. Crocco and her colleagues, “Deliberating Public Policy Issues with Adolescents: Classroom Dynamics and Sociocultural Considerations.” These authors analyze classroom “deliberations” of current events and find disappointing results. Their analysis is rigorous and insightful. One finding particularly caught my eye.

It is interesting that even students at the school with a large immigrant population tended to talk about immigrants as “they” when they deliberated about national policy. They were essentially role-playing the government or perhaps a body of influential citizens of the United States. As Crocco and her colleagues write, “Participating in the public debate about immigration in U.S. classrooms positions one as an insider with all the privileges of excluding outsiders that result from this status” (Crocco et al., 2018). This is evidence that the students experienced the discussion as a kind of role-play.

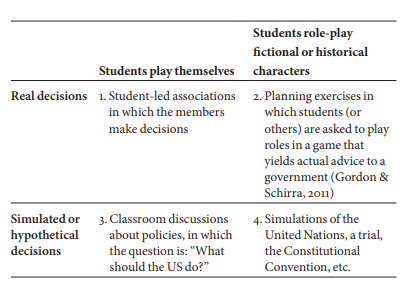

That finding leads me to propose that discussions can vary on two dimensions. Talking can result in an actual decision, or it can be about a simulated or hypothetical decision. And the participants can either speak for themselves or role-play characters. Those distinctions produce four types, all of which can be found in actual classrooms (and in settings for adults, such as community fora.)

I think Crocco et al. provide some grounds for skepticism about simulated decision-making discussions in which the speakers represent themselves (cell 3). When we ask students (or adults) to discuss what “we” should do, where the “we” is actually a vast or distant entity, such as the US government, we position them as insiders even though they know they are outsiders. This disjunction could be fun or interesting, but I think often it just alienates.

The other cells are more promising. It’s better to be able to: (1) govern a real entity, such as a student-led association, (2) give advice to a real decision-maker, or (4) pretend that you hold a decision-making role, such as a Senator in a fictional Congress.

There are benign reasons to turn national issues into topics for small-group discussions. The goal is to make students (or others) feel that the government is theirs. It does belong to them, as a matter of justice, and it’s great if they take away that feeling. But we must be serious about their limited power, or they will perceive the discussion as fake and perhaps draw the conclusion that democracy is fundamentally a false promise. As I write in the article:

The students in these three classes did not actually decide about immigration. At most, they might shift their individual opinions on that topic, and if they encouraged others outside the class to change their opinions in similar ways, that could possibly affect national policy by influencing those people’s votes. But that is a remote form of impact for any citizen to consider, and especially for students who are not old enough to vote themselves. The United States is an “Imagined Community” (Anderson, 1991), not a group of people who literally make decisions. The real group—a classroom full of students—was pretending to deliberate.

That is how I would explain why the results were disappointing.

Inaugural Hidden Common Ground Report Released

NCDD member org, Public Agenda, in collaboration with fellow NCDDer the Kettering Foundation have recently released the inaugural report of their Hidden Common Ground Initiative. This is an effort which seeks to dive deeper into issues that have been polarizing, in order to illuminate where there is common ground; with the hopes of better uniting the public around concrete, actionable solutions. This first round of research explores incarceration, and the following report that is slated to be released in May will revolve around healthcare. You can read the press release from Public Agenda below and find more information on the Hidden Common Ground Initiative here.

New Research Initiative Fights Narrative of Absolute Division of Americans on Critical Issues

![]() Inaugural project of the Hidden Common Ground Initiative elevates areas of agreement on incarceration and criminal justice reform in America

Inaugural project of the Hidden Common Ground Initiative elevates areas of agreement on incarceration and criminal justice reform in America

The state of America’s national politics has led many to believe the country is irreparably polarized and gridlocked. Recently, a storyline has taken hold that portrays this dysfunction as a reflection of our profound divisions as a people. However, a new research initiative launched by Public Agenda, in collaboration with the Kettering Foundation, shows that Americans can find common ground on many of the problems our nation faces.

It has taken decades for our national politics to become as polarized as it is today, leading to stagnation on critical issues like gun control, immigration and health care. While it is important to acknowledge the differences and disagreements that do exist, our divisions are hardly the whole story. The Hidden Common Ground Initiative aspires to tell the story of where the public agrees on concrete, actionable solutions and make those areas of agreement more salient and potent in our public life.

“We believe that dispelling the myth that we are hopelessly divided can not only help fuel progress on a host of issues, but also help us better navigate our real, enduring divisions.” said Will Friedman, President of Public Agenda. “We are grateful to have the Kettering Foundation as a collaborator on this initiative that has the potential to fight the often-inflated narrative of an America that is so divided, progress is impossible.”

The Hidden Common Ground Initiative will explore a variety of issues facing our nation and will include the release of a series of reports on our research findings. The first report, “Where Americans See Eye to Eye on Incarceration,” focuses on hidden or otherwise underappreciated common ground in the realm of incarceration and criminal justice reform.

In cross-partisan focus groups held around the country, reinforced by a review of existing survey research, we learned that:

-

- The focus group participants felt incarceration serves important functions, such as keeping dangerous people off the streets, but agreed that the criminal justice system can be unfair and make mistakes.

- Participants were strongly focused on preventing people from becoming criminals in the first place.

For drug crimes, and possibly some other nonviolent offenses, alternatives to incarceration made good sense to most people in the focus groups. But they were unwilling to accept alternative sentencing for violent crimes.

- Eliminating mandatory minimum sentences was a confusing, unresolved issue for participants.

Focus group findings are summarized in the new report, “Where Americans See Eye to Eye on Incarceration.” Three focus groups were conducted in September 2017 across the United States in urban Hamilton County, Ohio; rural Franklin County, Missouri; and suburban Suffolk County, New York.

The next report from the Hidden Common Ground Initiative, scheduled to be released in May, will explore how people talk across party lines about the problems facing our health care system and what people agree should be done to make progress.

You can read more about the Hidden Common Ground Initiative on Public Agenda’s site at www.publicagenda.org/pages/hidden-common-ground-where-americans-see-eye-to-eye-on-incarceration.

Katie Lisa

As Director of Development, Katie works collaboratively with senior staff to raise funds for Public Agenda's projects and operations. Prior to joining Public Agenda, Katie was the Associate Director of Institutional Giving at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City and she worked for six years at the Brooklyn Museum in many capacities, including Interim Co-Head of Development and Senior Development Officer. Katie brings with her a wealth of experience in fundraising and development, having worked as the Associate Director for Donor Stewardship at Columbia College and the Grants Writer at the Osborne Association, an organization that works with incarcerated populations and their loved ones.

Katie has a Master's from Columbia in Fundraising and Nonprofit Management and a Bachelor's degree from Rutgers College, where she graduated with honors.

Email: klisa@publicagenda.org

Trump at the confluence of populism, chauvinism, and celebrity

Donald Trump says many things. Some are innocuous and banal. Quite a few are inconsistent. And some provide evidence that he belongs in these three categories:

- A “populist” in the particular sense proposed by Jan-Werner Müller. (I also like to retain more positive definitions of the same word.) For Müller, a populist is someone who believes that the whole authentic people is unified behind a set of values that the populist leader explicitly expresses. Therefore, the opposition is illegitimate. Elections that favor the populist leader are sacrosanct, and anyone who criticizes or strives to reverse these results is an enemy of the people. But elections that challenge the populist must have been rigged or stolen. “A los amigos, justicia y gracia. A los enemigos, la ley a secas.”

- A chauvinist, meaning someone who explicitly and apologetically favors an in-group and disparages an out-group. In the United States, racism is a major variety. But in some other countries, the leading chauvinists are inspired by religion or nationality instead of race.

- A media personality who projects a combative personality, who disparages opponents, who cultivates “outrage,” who “seem[s] to always react to controversy and even aversion by leaning into it,” and who claims honesty or authenticity on the basis that he says things that give offense or cause pain–except not to his core audience. This style is prevalent on talk radio, certain reaches of cable news–but equally important, in supermarket tabloids, WWF, and reality TV shows like The Apprentice.

These three categories need not intersect. You can be an outrageous media personality who isn’t a populist or a chauvinist, a chauvinist who isn’t a celebrity, etc.

None of these categories is new. White Supremacy has been near the center of American politics since the beginning. Various forms of populism and chauvinism were much more extreme around the world in 1939 than today. But there does seem to be a global boom of unapologetic chauvinist populists who use media effectively.

The right doesn’t own these categories, and the left doesn’t consistently avoid them. I know plenty of people who believe that the Tea Party is pure Astroturf, a creature of right-wing billionaires. That is a populist move in Müller’s sense: it declares a large number of actual Americans to be illegitimate participants in politics. By the way, it’s different if you hate and fear your political opponents. That is partisanship, but not populism, so long as you acknowledge that your opponents are fellow citizens and you must share politics with them.

We’ve seen plenty of examples of these categories, but we have never had a president who fits all three. The combination poses a severe threat to our institutions and world peace.

Insofar as the problem is populism (in Müller’s sense), then I think an electoral shellacking will be the best remedy. Even if Republicans lose the 2018 election badly, the strongest Trump supporters (30-40% of the population) will continue to think that he speaks for the whole genuine American public and the election was rigged. However, Trump can’t govern without conservative and business elites. I think they will abandon him if they see that he is dragging them into the minority.

By the same token, if Republicans do better than expected in ’18, and/or Trump is reelected, we are in for much more populism. And if Trump’s presidency ends for a relatively extraneous reason, such as personal criminality, then the picture will be muddy enough that populism will remain an attractive option. (I often think that we are fortunate in our populist; if he were smarter and more disciplined, we would really be in trouble.)

Apart from elections, we have two other assets in the struggle against Müller-style populism. One is pluralist populism , which portrays “the people” as highly diverse (I discuss that rich tradition here).

The other is genuine conservatism. Real conservative thought is diametrically opposed–in principle–to the idea that any government can ever be authorized by a unitary public. The left/right spectrum originated in the French Revolution, and the Jacobin left was the populist side, in Müller’s sense. Conservatism emerged in reaction to the revolutionaries’ claim to a popular mandate, and great conservative thinkers have always opposed such claims. Many Republican politicians will go along with Trumpian populism as long as it wins elections; but conservatives will denounce it from the rooftops. The question is how many conservatives actually exist.

Insofar as the problem is chauvinism (meaning, in the USA, racism, religious bigotry, and sexism), then it’s the next chapter in a basic American story. Progress is hard-won and tends to have a zigzag pattern. I am a fan of Barack Obama for other reasons than his race, but it is significant that he was the first leader of a majority-white nation to have modern African ancestors–and the first US president in modern times to have a foreign father. That was the zig; Trump is the zag. The struggle continues.

Finally, insofar as the problem is celebrity politics, I am actually optimistic. I believe that Trump came first in a crowded and splintered Republican primary field because his persona appealed to a minority of the US population. He then beat Clinton in the Electoral College because partisan polarization gave him most Republican votes in key states, and she was deeply unpopular. Compared to a generic incumbent president who enjoys a strong economy and who hasn’t actually passed any controversial legislation (other than a tax cut), Trump is remarkably unpopular. And a key reason is his style. So I think acting like a reality TV star exacts a political cost and is not likely to be replicated.

Focus Group Discussions as Sites for Public Deliberation and Sensemaking Following Shared Political Documentary Viewing

The 27-page article, Focus Group Discussions as Sites for Public Deliberation and Sensemaking Following Shared Political Documentary Viewing (2017), was written byMargaret Jane Pitts, Kate Kenski, Stephanie A. Smith, and Corey A. Pavlich, and published in the Journal of Public Deliberation: Vol. 13: Iss. 2. From the abstract, “This study examines the potential that shared political documentary viewing coupled with public deliberation via focus group discussion has for political sensemaking and civic engagement”. Read an excerpt from the article below and find the PDF available for download on the Journal of Public Deliberation site here.

From the introduction…

While the field of political communication has paid attention to the importance of entertainment media in the last decade (e.g., Hmielowski, Holbert, & Lee, 2011; Young, 2004), little research has focused on political documentary as an influential medium and source for public deliberation and meaning-making (Nisbet & Aufderheide, 2009). A few studies have shown that political documentary has the potential to influence public perceptions and behaviors. For example, Howell (2011) found that UK viewers became more pro-environmental after being exposed to a film depicting the negative effects of climate change. Stroud (2007) found that the viewers of the documentary Fahrenheit 9/11 were more likely to discuss politics with friends and family than were non-viewers. Related research has demonstrated that mass media generally, and political film and documentaries specifically, can enhance learning in the classroom (Krain, 2010; Sunderland, Rothermel, & Lusk, 2009) and influence the electorate (LaMarre & Landreville, 2009). Additional research has shown that combining media viewing with deliberative discursive engagement can further increase positive civic outcomes (Kern & Just, 1995; Rojas, Shah, Cho, Schmierbach, Keum, & Gil-De-Zuñiga, 2005). This may be in part due to the greater potential for collaborative sensemaking—the negotiated and discursive engagement in shared meaning making that happens during public deliberation (see Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, 2005). However, opportunities for collaborative sensemaking and public deliberation centered on a popular text are rare. Thus, we were interested in exploring focus groups as a potentially rich context for discursive engagement following the shared viewing of a political documentary (i.e., 2016, Obama’s America). We argue that when placed within the context of viewing popular political documentary, focus group discussions offer a meaningful site for public deliberation and collaborative sensemaking and as such should be added to the toolbox of deliberative pedagogy.

Download the full article from the Journal of Public Deliberation here.

About the Journal of Public Deliberation![]()

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen-friendly form.

Follow the Deliberative Democracy Consortium on Twitter: @delibdem

Follow the International Association of Public Participation [US] on Twitter: @IAP2USA

Resource Link: www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol13/iss2/art6/

NWOC Partner Shares Piece on Hearing Every Voice

The National Week of Conversation is wrapping up tomorrow, April 28th, and many across the nation have participated in this collective movement to bring Americans together to talk and heal divisions. Which is why we wanted to lift up this piece that fellow NWOC partner AllSides recently shared on their Perspectives blog on Hearing Every Voice written by Tom McSteen of Sacred Discourse. The article talks about the experience of connecting through conversation in a way that honors every voice present and the importance of utilizing structures like those of Living Room Conversations, also a partner of NWOC and an NCDD member. Read the post below and find the original on AllSides site here.

Hearing Every Voice

![]() How do you feel when your voice is heard? How do you feel when it is not?

How do you feel when your voice is heard? How do you feel when it is not?

We all want our voice to be heard. We all want to feel self-expressed. We all want to leave a gathering where we had something to say, having said what we wanted to say. If that does not happen, feelings of frustration, disagreement, and aloneness can creep in. These feelings, particularly when experienced over time, can lead to states of separation and division.

Unsurprisingly, I have experienced many conversations and public events where I felt my voice was not heard, from extended family gatherings at holidays to governmental forums on whether to build pipelines. Leaving these situations with the experience of not being heard left me feeling isolated.

Hearing every voice can be literal, as in taking the time at a particular gathering to give everyone a chance to speak. It can also be figurative, when people feel in some collective way that their views or experiences have been dismissed. This figurative example is often seen in national elections, when groups of people feel glossed over and unheard. Yet, this state is more likely to develop over time when there are not tangible forums for people to fully eexpressthemselves.

We have choices, both in the literal and figurative sense. We can act so as to not hear or marginalize certain voices, to selectively hear only what we want to hear. When we do so, however, we add, often unintentionally, to the current division in our politics, our public discourse.

Or, on the other hand, when we intentionally make an attempt to hear every voice, in any setting on any topic, literally or figuratively, we create the possibility of conversation or discourse that is more inclusive and connective.

When people do not feel heard, they are more likely to be dismissive of others’ voices. And, when people feel heard, they are more likely to allow others to be heard, in turn.

It may not always be easy or simple to create the space for every voice to be heard. But it’s possible. Setting rules of engagement and establishing a safe and clear container in a structured environment are two key ways to allow for every voice to be heard.

The new and rising organization, Living Room Conversations, provides a safe place to hear every voice. Having been a part of multiple conversations using this methodology, I know firsthand that people with very different points of view can come together and have a civil conversation. And, most importantly, they can walk away with a new understanding of the “other.”

A key differentiator, perhaps, is a well-stated intention to hear every voice no matter the setting. Whether in families or at the office, imagine what is possible when there is a concerted effort to hear all voices. Business journals, as an example, laud corporations that invest the time and effort into really providing time and space to listen to each and every employee. Could not the same be true for public discourse? Particularly for local issues, town halls can be a forum where there is a clear intention to give time and space to hear every voice on a given topic.

The experience of being heard can go a long way toward acceptance of a decision that goes against what I want to happen. When I feel that I have had the opportunity to express myself fully, and I feel the self-respect that comes from being able to do so, I can much more easily accept whatever the decision may be, even if I disagree with the outcome.

Might this simply be a return to respectful dialogue? In early April, the organization A Peace of Mind set up a studio at a leadership conference focused on cultivating civil discourse. They asked participants, “How have you cultivated civil discourse in the past year?” The responses were wide-ranging, and they provide numerous examples of what people can do to promote this practice.

One participant said: “I try to really learn about the speaker’s perspective and not just wait for them to pause so I can jump in and talk.” What a difference this could make toward returning to an experience of civil discourse that is respectful and constructive and that does not separate and divide.

As we move forward to the 2018 national elections, and then on to the 2020 presidential elections, what are ways that we each can be sure that those voices, particularly of people with whom we disagree, are heard? What community forums might we create to give people an opportunity to fully express their beliefs and concerns?

In addition to creating the forums, it helps to prepare people for these conversations. That is what we do at Sacred Discourse, following a relational framework that supports a shared intention to leave the others in a conversation feeling more whole, inspired, and connected after the conversation. Our framework begins with a commitment to hear all the voices, because without including everyone, we cannot move forward together.

You can find the original version of this article on AllSide Perspectives blog at www.allsides.com/blog/hearing-every-voice.

ENGAGING IDEAS – 04/27/2018

Michael A. Rebell, Flunking Democracy: Schools, Courts, and Civic Participation

This is a very important new book: Michael A. Rebell, Flunking Democracy: Schools, Courts, and Civic Participation (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

My blurb on the back cover says, “Michael Rebell makes a powerful and original case that litigation can and should improve civic education. He skillfully assembles evidence from the existing literature to show that civic education is important for the future of our democracy and requires improvement, then further applies his deep knowledge and experience with education-reform litigation to argue persuasively that courts can and would consider lawsuits requiring states to improve their policies for civic education.”

I’d add that this is one of the best available summaries of the research on civic education. Rebell really does demonstrate that litigation is a plausible strategy for improving civics. One reason is that state constitutions often explicitly cite preparing citizens to vote and serve on juries as the main rationale for establishing a right to education. Finally, Rebell offers sophisticated solutions. In a way, the hardest question is what a state should do if a court orders it to improve its civic education. There are complex debates about the value of policies like tests and required courses, and no single policy will work in every state and for every purpose.* But Rebell explains that courts can require processes that involve deliberation about strategies, experimentation, and assessment. That means that a court wouldn’t have to order a policy but could require a flexible process and then hold the state accountable for making serious efforts.

* See my exchange with Beth Rubin about policy for civics, new overview of civic education, and state policies for civics: it’s all about implementation.

Creating a Welcoming Environment with Conservatives

As people convene this week for the National Week of Conversation, we wanted to share this piece from NCDD member org, The Village Square – Tallahassee on how to build authentic relationships and civic events with conservatives. In order to truly engage the public, it’s vital to have an actual diverse group. Often times, particularly in the D&D field, the same “usual suspects” of left-leaning folks are gathered and Conservative-identifying are left out. The Village Square talks about the important lessons they have learned on how to create a more welcoming environment and create a space where Conservatives are more inclined to come to the table. We encourage you to read the article below and find it in full on The Village Square – Tallahassee’s site here.

Welcoming Conservatives

As a critical mass of appropriate hand wringing continues as to how to address the deep and increasingly consequential partisan divisions roiling the western world, there is a surprisingly well-developed empirically supported body of knowledge that guides solutions that seem far simpler than the enormity of the problem would suggest.

As a critical mass of appropriate hand wringing continues as to how to address the deep and increasingly consequential partisan divisions roiling the western world, there is a surprisingly well-developed empirically supported body of knowledge that guides solutions that seem far simpler than the enormity of the problem would suggest.

To grow empathy toward those with different worldviews, moral psychologists tell us, we need to have positive interactions with “the other” (which is referred to as “contact hypothesis”) and emphasize shared “superordinate” goals. Our decade of pushing the civility rock up this steep hill supports their science – it’s almost a secret decoder ring because it shifts entrenched negative attitudes reliably and quickly. Strangely enough, softening hatred turns out to have been the easy part of this big job. The hard part is getting people who disagree on politics to occupy the same space so that the magic can work.

For those of us inspired to the work of building bridges, this first step of getting people with diverse views in a room together has proven a frequently experienced circular challenge – we don’t like each other because we don’t spend time together and we don’t spend time together because we don’t like each other.

This challenge appears to be particularly thorny when it comes to drawing conservatives into civic engagement as it’s most typically practiced. After a decade of experience with the Village Square – an organization dedicated to creating relationships across the partisan divide – we’ve developed some thinking around both causes of the problem and solutions that work. We host about 30 events a year that depend on drawing a voluntary diverse audience – because no one has to attend our events, we’ve been forced to do both sleuthing and soul searching.

As brilliant new ideas are popping up around the country to address the challenge of poisonous tribal partisanship, we think there is significant risk that too many of these good ideas will fail to achieve their goals simply because they fail to draw conservatives into their orbit. Even brilliantly conceived and potentially highly impactful initiatives may make things arguably worse, after all if conservatives don’t show up, aren’t we accidentally cementing structural divisions by hanging even more often with fellow liberals? And might we risk driving the contempt even deeper, when liberals who show up and want to fix “the relationship” are effectively “stood up?” Note: we’re addressing our remarks to liberals struggling to draw conservatives into dialogue. Further posts will address other aspects of this challenge!

Here’s what we learned

Start with a bipartisan relationship. Whatever you’re undertaking, your team has to include a minimum of two people with an authentic ongoing relationship who disagree on politics. If your first try at this fails, try again. If you don’t have a relationship like this, build one. There is no group of politically likeminded people, no matter how well meaning, who will ultimately succeed in an endeavor lacking some honest feedback from the other side. Conservatives will probably be less intrigued by your idea (for reasons we touch on, below) so you might have to be creative in how you meet this requirement as you begin. But do meet it. You might also have to live with the idea that they’re less “in love” with your idea or project than you are at first. That’s all worth moving past because a truth-telling conservative partner will tell you important things that you will never imagine otherwise.

Build an expanding bipartisan network incrementally. Depending on the durability you’re trying to achieve or the scale of your endeavor, consider growing an intermediate-sized ideologically and demographically diverse group that essentially creates the social “glue” that will ensure you draw from different tribes when you either go big or go long with the public. For us it was a bipartisan board of about 15 (the liberal partner in the original pair identified conservative friends and vice versa), then that group expanded to 75 “founders” before we did our first press release. To the extent you can, keep tapping pre-existing friendships to form the strongest base going forward. Early on, there was much vouching we had to do for each other with potential panelists, elected officials and members of the public. They were suspicious.

Keep a conservative bench. You’re more likely to lose conservatives along the way (again, for reasons that make perfect sense and have nothing to do with their moral compass, see below). Don’t get irritated – just get replacements. Do take the time to get feedback from conservatives you’ve lost – you might even learn something! Wash, rinse, repeat. Forever.

Consider partnering with an ideologically diverse church congregation or a politically diverse group of churches. Churches are institutions that have more street cred for conservatives than the average town hall does. Additionally, church partners naturally help you speak to hearts, not heads (below).

If you’re liberal, don’t use your mother tongue. Direct appeals to “unity” can have an unintended effect in this dysfunctional highly siloed political environment – where individual words even have tremendous partisan valence. Efforts to unite across division – often led by citizens who lean liberal (for reasons that have nothing to do with the worth of conservatives) – unintentionally and understandably frame their efforts using language that draws in like-minded liberal audience. In this way their framing unintentionally conveys to conservatives that the project is a liberal one, predisposing a failure to engage conservatives adequately.

Here’s a list of some hot potato words you might want to avoid in your official communications (or at the very least balance them with some words that speak to conservatives). It isn’t that conservatives don’t care about some of these things, it’s just that in this polarized environment they’ve become toxic markers of partisanship and should be used only with caution by bridge builders who truly want to build the gosh darn bridge: sustainability, race, unity, cooperation, community, social justice, awareness, women’s health, tolerance, climate change, privilege, resources, diversity, dialogue, inclusive, identity, kindness. (We’re sorry, we know this is hard news because we’ve been there too. When our civic space is detoxified, we can use them again.) We make a practice of checking the titles of our programs with both liberal and conservative friends.

Speak to hearts, not heads. Corollary: focus on relationships, not facts. A unique quality of Western liberalism is that we perceive ourselves as operating inside a framework of rationalism where we look at the facts, weigh them and choose the course of action that is objectively supported. But if we truly value facts, we’ll realize that rationalism isn’t – well – rational. For human beings making our way through copious and ambiguous information, science tells us that our intuitions comes first, and strategic reasoning follows. We essentially – as a species – believe what we want to believe (liberals too).

Forums with a heavy focus on debate and fact checking put the cart squarely before the horse in terms of what has to happen first to create change. The primary focus on bridge building efforts has to be on creating conditions that make people from feuding tribes want to like each other. Once those positive relationships exists, we want to hear others out, which changes everything. Interestingly, many conservatives follow their intuition first as their factory default setting, so in a highly divided political world, they immediately sense your liberalism when your coordinates aim squarely and repeatedly at objective fact. We know, waiting is hard to do. But the cart will come along if you get the moving parts in the right order. (We have a priest friend who likes to challenge our audiences to list the guiding principles of their lives using only facts. Can’t do it can you? Big ideas incorporate wisdom and wisdom is different than fact.)

Understand liberal and conservative “moral channels.” Liberals and conservatives are not receiving information about our current civic crisis on the same channels and it’s a fundamentally big problem. According to Jonathan Haidt and colleagues’ body of work advanced as Moral Foundations Theory(entertaining 18 minute primer here), liberals understand moral good to be constrained primarily to whether it is caring or harmful and whether it is fair. While conservatives also believe that care and fairness are moral goods, they believe those goods must be balanced with other moral goods (loyalty, authority, liberty and sanctity – referred to as the “binding” moral foundations).

In this polarized political environment, The Village Square has considerable direct experiential evidence that anything that sounds like attention to care and fairness actually drives conservatives away, as they intuitively understand “this is not my tribe.” Making matters worse, liberals perceive that in many cases conservative moral values are, in fact, amoral, responding to this perception with even more care and fairness (the concept of “virtue signaling” is useful in understanding this tendency). This caring on steroids often has the unintentional effect of creating a backlash with conservatives rather than building the bridge liberals truly do seek. To conservatives this kind of an over focusing on “care” and “fair” feels immature (lacking in broad situational awareness and some critical qualities a healthy society must have to function, like authority) as well as too often weaponized by “social justice warriors.” The more conservatives hear “care more,” the more they actually seem to do the opposite; the “meaner” liberals think conservatives are, the stronger liberals catapult the “care” into the next round of hostilities. This is the cycle of equal and opposite reactions where the worst in our politics now resides.

Believe in your soul that without deeply engaged conservatives, your effort will lack critical insights required to solve problems – insights liberals are likely blind to (even dangers liberals may be blind to). We often encounter liberal-leaning friends and colleagues doing civic work with incredibly sincere intention, but with a little digging it’s clear that their central animating belief is that if one can create respectful conversation and do good fact checking, ultimately those intransigent conservatives will come around to a more liberal view of reality. In our era of jaw-dropping distortion of factual reality, we understand the impulse to see the problem this way (truth told, this describes many of us). But as valid as this aspect of the challenge is, you’ll have much more success if you begin with another deep truth we’ve discovered along the way: conservatives can often see dangers, risks and challenges that liberals can’t. All humans have significant blind spots in our ability to perceive reality and likeminded groups of people are even more prone to blindness (a moral tribe actually is glued together aroundthose blind spots).

We like John Stuart Mill on this: “… the besetting danger is not so much of embracing falsehood for truth, as of mistaking part of the truth for the whole. It might be plausibly maintained that in almost every one of the leading controversies… both sides were in the right in what they affirmed, though in the wrong in what they denied; and that if either could have been made to take the other’s views in addition to its own, little more would have been needed to make its doctrine correct.”

The shift in your organizing premise will come through clearly to conservatives and it will draw them to you. For more, see the concept of “morality binds and blinds” in Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind. (Think of this blindness as akin to the dark side of the “asteroid” in our Asteroids Club metaphor.)

Empathize with conservatives through a key insight that’s commonly absent in liberal circles. In American Grace, Harvard’s Robert Putnam broadly observes that as tectonic plates moved in society beginning in the sixties – and since – liberals have won the culture war on most all fronts. We get it, if you’re liberal we’re still not there, but if you’re 50 years old pretty much everything has changed about our social order in the length of your life. From this vantage point, even just that level of change can be thoroughly disorienting, especially if you believe in conservative principles that follow the wisdom of the ages. That means that for over a half a century, conservatives have been living in a culture that violates their most essential guiding principles about how to maintain a functional society (don’t mistake that as being just about bias against women and minorities, it’s not).

Liberals are now less than one year into a presidency that violates their deepest held core beliefs about what constitutes a strong and healthy world. The natural (and healthy) reaction for liberals is they’re now circling their wagons and gathering in common cause to push against it. And in that short time, there’s already been reporting on the rise of “fake news” on the left. Bad facts on the right are inevitable after decades of feeling outside the prevailing culture, given that human beings “reason” in order to confirm what we want to believe, not what’s objectively true. Imagine the left in 50 years of a Trump-styled illiberal democracy and you’ll have more empathy.

Take a continuous meter reading on whether the environment you’ve created welcomes conservatives. A lost liberal who stumbles into a gun show wouldn’t need to see a single firearm to know they’re not with their people. Conservatives will know too. It’s a good exercise to think of everything you do through their eyes.

Scale up using a distributed leadership “cell” model. (Alternative less-advisable name: “Use the al Qaeda model”) Whether you’re going for clicks, attendance, or some other kind of scale, look to a small key group of catalysts to become separate “hubs” to build a diverse audience. The very problem we face is that ideologically diverse groupings of people aren’t naturally occurring “in the wild” so you can’t just assume diverse people will naturally show up for you because you want them to. Creating diverse groups now requires a new intentionality.

A “cell” structure has long been powerfully deployed to create worldwide terror, or if you’d prefer something morally worth emulating, cells create the close connections that form the organizing ballast of megachurches. Point is, it works. Almost all of us can find 7 people who look and think different than we do and invite them to join us to do something. We’ve used this model to draw a racially diverse audience of 500+ to actually talk about race – we only needed 20 diverse catalysts to get it done. Once the engineered diversity starts shaping attendance, its momentum makes a diverse audience now grow naturally. Voila, you’ve essentially begun formation of a new tribe.

Recognize the hazard of lopsided groups. Truth is, we’ve had plenty of politically lopsided groups, it’s even possible that all of our now hundreds of events have had lopsided attendance (our original location is in a highly liberal city). You can do everything right and it’s still likely your engagement will lean left (spending an evening immersed in dialogue across diversity can seem to conservatives like a liberal thing to do). But it is critical that you stay highly aware of the imbalance – it will affect every decision you make toward keeping conservatives comfortable and lead to increasing success attracting conservatives into your project over time.

Respect that conservatives are going to be less thrilled with your forum or initiative for reasons that are truly legitimate (and have nothing to do with being mean, overly partisan or racist). It is simply a descriptor of the essential philosophical underpinnings of conservatism that they have moreconfidence in their families and faith communities to deal with problems than government or a shared civic space. What this means is that the very nature of most civility initiatives begins with a frame that many conservatives don’t fundamentally share with their more liberal neighbors. An incredible strength of so many conservatives we know is that they’ve got their guiding principles and they’re a little too busy following them to make it to an evening forum. We’ve learned that ultimately it’s our deep embrace of what they bring that’s unique that’s made all the difference.

Challenges notwithstanding, the rewards you’ll get for your efforts to welcome conservatives are both essential to your success and will be transformational for you. They have been for us – the liberals among us will never go back to a room full of people just like us. It’s boring and lacks insights we’ve grown accustomed to hearing.

Got more ideas, models that have worked for you or do you just basically disagree with something we’re advancing here? Building bridges is a big job so we’ll need all shoulders at the wheel. Let’s keep talking.

You can find the original version of this article on The Village Square – Tallahassee’s site at https://tlh.villagesquare.us/blog/welcoming-conservatives/.