In a dialogue with his disciple Tsze-kung, Confucius advises that a government needs three things: weapons, food, and trust. And if a ruler cannot maintain the three of them, he should give up the weapons first and the food next.

Fast forward over two thousand years, and trust in government remains a hot topic. After all, rule of law and democratic institutions clearly require some minimal consent and trust in government. And, to varying degrees, the success of most public policies and programs, from paying taxes to recycling, depends on citizens’ compliance and cooperation.

Trust in government has also generated increased interest during the pandemic. For example, in an article for The Atlantic, Francis Fukuyama described trust in government as the most important predictor of a government’s capacity to respond to the ongoing health crisis. His argument is intuitive: particularly during times of crisis, discretionary authority needs to be delegated to executive branches, as “no set of preexisting laws or rules can ever anticipate all of the novel and rapidly changing situations that countries will face”. In that context, so goes the argument, “citizens have to believe that the executive knows what it is doing.” Fukuyama’s take on the importance of trust during the pandemic resonates with evidence from previous health crises and, not surprisingly, scholarly interest in the subject has soared since the outbreak. Confucius’ argument still resonates.

Equally interesting, however, has been the emergence of a public debate that also asks whether, in some cases, trust in government may be unwarranted. For instance, reporting on the health situation in Lebanon, a Washington Post article highlighted that “paradoxically, distrust of the notoriously dysfunctional government may have helped.” In a similar vein, The Economist argued that, during an epidemic, trust can be a “double-edged sword”. The behavior of many political leaders in downplaying the seriousness of the crisis has also illustrated how, in certain cases, distrusting the government is the healthiest option available.

These insights run counter to the conventional wisdom, which tends to consider trust in government as a good in itself. For instance, a frequent selling point for open government reforms is the (often misleading) claim that transparency will lead to increased trust in government. But it shouldn’t take a pandemic to realize that trust in government can also be overrated. Checks and balances, foundational to the modern state, were built upon the premise of distrust. For Montesquieu, the separation of powers was necessary to avoid exposing citizens to “arbitrary control.” David Hume cautioned that when designing government systems, “every man ought to be supposed a knave.” And, for Madison, “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

But if there are good reasons to trust in government, as well as good reasons not to, when is trust more or less appropriate? This is certainly a complex question, and the purpose of this post is by no means to provide a definitive answer. Instead, it aims to put forward a very simple (and perhaps simplistic) framework to start thinking about the imponderable problem of trust in government according to its context.

To understand the proposed framework, we can start with the following premise:

All else equal, individuals’ trust in their government should be expected to be proportional to the trustworthiness of that government.

This premise, I believe, is uncontroversial. As put by philosopher Onora O’Neill, trust is valuable only “when placed in trustworthy agents and activities, but damaging or costly when (mis)placed in untrustworthy agents and activities.”

But how do we define trustworthiness? Any attempt is bound to generate contestations, as has been the case for the definition of trust in government. For the purpose of this exercise, I borrow a definition from Margaret Levi, a prominent scholar on the subject, who considers a government to be worthy of citizens’ trust when it

(…) keeps its promises (or has exceptionally good reasons why it fails to), is relatively fair in its decision-making and enforcement processes, and delivers goods and services.

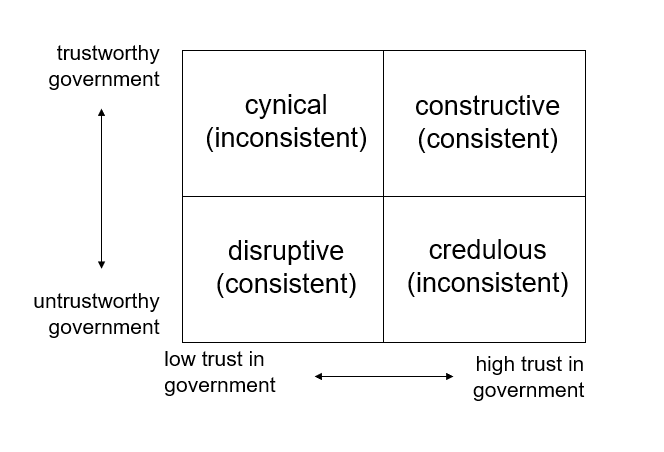

With this definition in mind, and the premise put forward earlier, the more a government keeps its promises, is fair, and delivers goods and services, the more citizens should trust that government, and vice-versa. If we depict the relationships between levels of trust and trustworthiness in a matrix, an interesting perspective emerges, as shown below:

Figure 1: Trust Matrix

In the top right and lower left (quadrants 2 and 3), we have scenarios of consistency, where citizens’ level of trust in governments corresponds to the level of government trustworthiness. In quadrant 2 we have scenarios of constructive consistency, characterized by a virtuous cycle where high trust leads to higher trustworthiness and vice-versa. In these scenarios citizens are, for instance, more willing to cooperate with government policies (e.g. taxation, vaccination), thereby enhancing governmental capacity to respond to public needs (e.g. public investments, disease control). Quadrant 3 represents scenarios of disruptive consistency, with disruptive meaning a context that can lead to both negative and positive developments. On the one hand, it may engender a vicious and destructive cycle whereby the government’s poor performance leads to less trust, further reducing the likelihood that governments are able to perform. On the other hand, it may lead to a process of creative destruction. After all, distrust of authorities often sparks democratic progress. In this respect, a context of disruptive consistency may open spaces of contestation and competition (e.g. through elections), generating incentives for political actors to perform better.

Quadrants 1 and 4 reflect scenarios of inconsistency, where the level of trust in government does not correspond to a government’s trustworthiness. In the cynical quadrant, despite government trustworthiness, citizens still show low levels of trust towards their government. Such a scenario is not free from implications: governmental policies may have disproportionately higher implementation costs, given that the public is less likely to comply and cooperate with these policies. In quadrant 4, (credulous), citizens trust their governments even though they are not deserving of that trust. In this scenario, untrustworthy governments have little incentive to change their behavior (e.g. delivering public goods and services), given that their citizens already trust them and do not present any threat to the status quo. This becomes a low-accountability trap, with citizens unlikely to engage to keep office-holders accountable for their actions in the public realm.

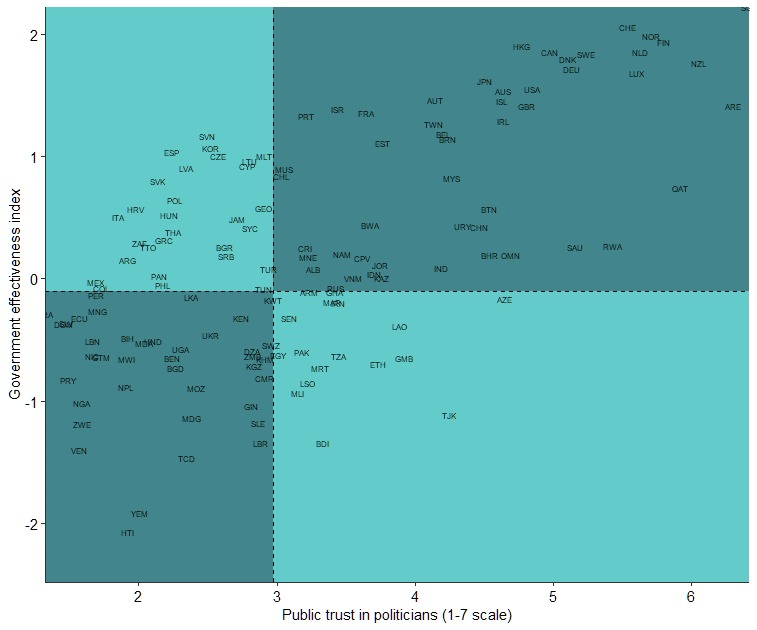

What does this all look like in practice? Into which quadrants do countries fall? While measuring trustworthiness goes beyond the scope of this post (more on that below), we can map it against existing indicators linked to trustworthiness, such as the Government Effectiveness Index, which captures, among other things, quality of public services, quality of civil service and governments’ commitments to their policies.

Figure 2. All over the map: the relationship between trust and government effectiveness

Source: author’s own based on Government Effectiveness Index (2020) and World Economic Forum Executive Survey (2018)

As the figure above illustrates, the 135 countries covered by the dataset fall into all four quadrants. Trust in government, as it turns out, is not consistently aligned with dimensions of government trustworthiness. Yet two-thirds of the countries (89) fall into the dark green consistent scenarios, indicating that in most countries, the level of trust in government is commensurate with the level of trustworthiness. This calls into question narratives that typically suggest a widespread crisis of trust in governments. Increased trust in government in this majority of countries would result in shifts towards situations of credulity: arguably the worst-case scenario, and a boon for women and men in power to behave more as knaves than angels. More importantly, the figure shows that increased trust in government emerges as a clearly desirable goal in just one of the four scenarios of the trust matrix (cynical, upper-left), where only 29 of 135 countries currently find themselves, including Argentina, Poland and South Korea.

Even if this framework may be reductionist, I believe it could still be useful for several reasons, a few of which I would like to highlight. First, the matrix gives us an indication of where trust in government may need to be increased or decreased. If one knows how to increase trust in government (and that’s a bold assumption), the framework provides some guidance on where it would make sense to start.

Second, these scenarios may help us better hypothesize which types of policy reforms would be desirable to pursue. For instance, in the scenario of credulous inconsistency (lower-right), the desirable outcome is that citizens become less credulous of their government and replace it through the ballots (in the case of a democracy), or dissent (in the case of an authoritarian regime). In these cases, potential activities could be efforts that i) increase transparency of government’s poor performance (to reduce trust), and ii) facilitate individual and collective action (to sanction poor performance). If these assumptions hold true in practice and at scale, and whether they can be voluntarily induced, remains an empirical question.

Finally, by adding trustworthiness as a variable, we expand our focus beyond “the eyes of the [governed] beholder” to a relational dimension in which governmental actions play an important role. By doing so, we also become more wary of hasty assumptions such as “transparency leads to trust”, where low trust in government is perceived more as a function of the opacity of a government’s behavior, rather than of its behavior. Which brings me to my next point.

Pathways towards consistency

If we consider that individuals’ trust in their government should be proportional to the trustworthiness of that government, we should contemplate the factors contributing to such consistency. Two are particularly noteworthy here: education and transparency.

As highlighted by Armen Hakhverdian and Quinton Mayne, citizens with a higher level of education are more likely to i) identify practices that negatively affect the functioning of government institutions, and ii) be normatively troubled by these practices. For example, the authors show that education is negatively related to institutional trust in corrupt societies and positively related to institutional trust in clean societies. If we consider that integrity is a property of trustworthy governments, education acts as a force creating consistency and moving away from cynical or credulous inconsistency.

But how do citizens identify, in the first place, the government practices that affect the functioning of institutions? One way is through personal experience: for instance, when citizens are either victims or witnesses of abuse by state agents (e.g. bribery requests, police violence). However, the most important way in which citizens identify these practices is through publicly available information on governmental actions. This brings me to the issue of transparency: its instrumental value is not whether it leads to more trust in government, as is often advocated. Rather, its value lies in its capacity to help individuals calibrate their trust vis-à-vis their governments, either towards more, or less, trust.

Final notes: measurements and definitions

One practical issue when it comes to trust in government is the availability of data. The most recent World Values Survey (WVS) has data on trust in government institutions for only 50 countries, the Gallup Poll for 43 countries, and the widely publicized Edelman Trust Barometer Survey covers no more than 28 countries. And by any count, there are at least 193 countries in the world. While claims about a global crisis of trust abound, global data about trust in government is less abundant.[1]

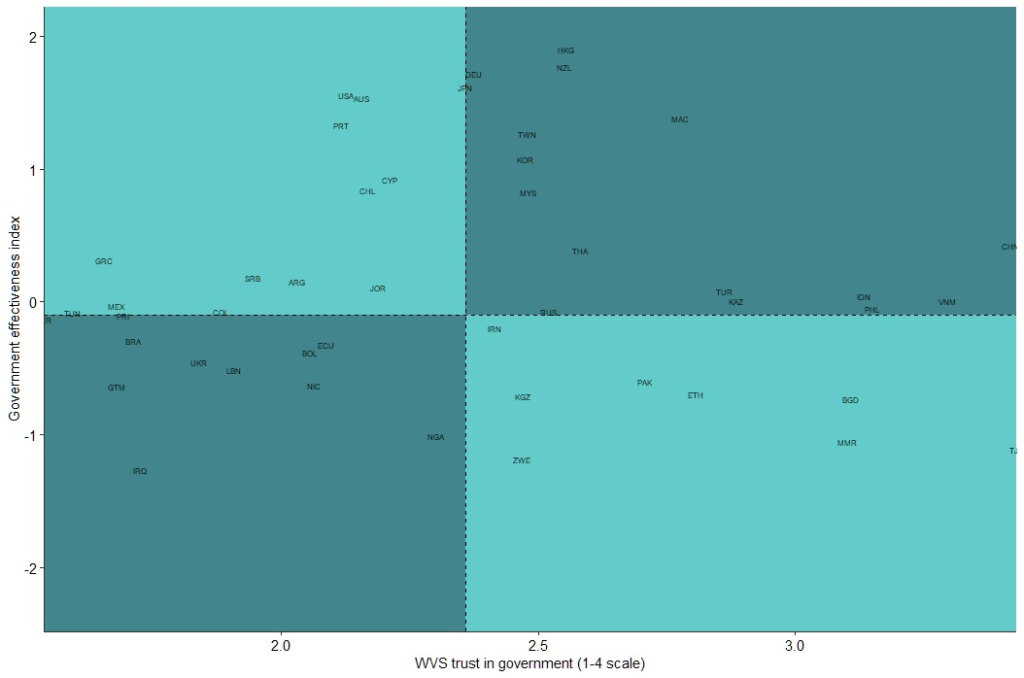

And which data one uses also matters, as illustrated below. For instance, when using data from the WVS, the countries falling under each quadrant differ from the results presented earlier (from the World Economic Forum’s Executive Survey). In short, different surveys will offer different results, each of them with their own shortcomings in terms of sample size, accuracy, or both.[2] In short, claims about trust in government, particularly at the global level, should be made carefully. Bearing these considerations in mind, the analytical framework put forward remains useful. Whichever indicator of trust one finds more appropriate to use, the framework still helps highlight in which cases trust in government is consistent or not with measures of government trustworthiness. In a passage of his most recent book, Ethan Zuckerman refers to “a sweet spot between too much trust and too little.” This framework, I believe, provides clues on where that spot may be.

Figure 3: Government Effectiveness vs Trust in Government (WVS survey)

Source: author’s own based on Government Effectiveness Index (2020) and World Values Survey (Wave 7)

A final note regarding the definition of trustworthiness is important. Levi’s definition certainly covers most of the characteristics that one would attribute to a trustworthy government, such as keeping promises, fairness in decision-making and enforcement, and delivery of goods and services. But as Levi highlights, the relative fairness of processes involves “the norms of place and time,” which makes fairness a concept that is contextual and of an evolving nature. This adds layers of complexity and raises some interesting questions, two of which I would like to highlight here.

The first regards the procedural and substantive dimensions of fairness and trustworthiness. In recent decades, many high-income democracies have performed well in procedural terms, with free and fair elections and laws that are mostly clear, stable, and equally enforced. From a procedural angle, these governments are worthy of trust. Nevertheless, on substantive grounds, one could contend that the opposite is also true. Take, for example, the overwhelming evidence that in these same democracies, government responsiveness has been systematically biased towards the needs of the better-off. Add to that growing inequality and a shrinking provision of public goods and services, and it becomes difficult to advocate for trustworthiness calculations based solely on procedural attributes.

As a side note, precisely because of the factors described above, one could say that part of the political polarization we see within countries today can be attributed to a growing divide between segments of the population that favor either procedural or substantive aspects of trustworthiness. For instance, some segments may privilege fair elections, while others attach more importance to substantive matters, such as bridging the gap between the rich and poor. Going back to the proposed trust matrix, the question then becomes whether trustworthiness should be assessed on procedural or substantive grounds and, if the answer is “both”, how to conciliate them. While answering this question brings its own normative and methodological challenges, evading it may fail to capture nuances that underpin the relationship between trust in government and government trustworthiness.

The second question is much simpler, albeit one with procedural and substantive consequences. Shouldn’t a government’s trustworthiness also be measured by the extent to which it offers participatory avenues for citizens to express themselves, beyond regular elections? After all, considering that trust is a two-way street, if governments expect to be trusted, shouldn’t they also trust citizens to shape decisions that affect their lives?

***

P.S.: I’m thankful for comments on earlier versions of this text from Amy Chamberlain, Jonathan Fox, Quinton Mayne, Jon Mellon, Hollie Russon Gilman, Paolo Spada and Tom Steinberg.

[1] On claims of a global crisis of trust see, for instance, here, here and here.

[2] On methodological challenges see Carlsson et al. 2018, Robinson and Tannenberg 2018, Shockley et al. 2017.

It’s been a while since the last post here. In compensation, it’s not been a bad year in terms of getting some research out there. First, we finally managed to publish “

It’s been a while since the last post here. In compensation, it’s not been a bad year in terms of getting some research out there. First, we finally managed to publish “