Monthly Archives: February 2018

The Women’s Advocacy Platform: Promoting Gender-inclusive Governance in Juaboso District (Ghana)

what is cultural appropriation?

Matt Walsh, who writes from the perspective of the religious right, garnered widespread attention after sharing his dismay that Christians indulge in “Hindu worship” like yoga. … It’s worth noting that he’s not necessarily wrong. Yoga derives from ancient Indian spiritual practices and an explicitly religious element of Hinduism …. Modern practice has been commodified, commercialized, and secularized, and has been as controversial among Hindu scholars of religion as it has among members of the Christian right. Last week, Shreena Gandhi, a religious studies professor at Michigan State University, published an academic paper critiquing how the modern Western yoga industry is a form of “cultural appropriation … intimately linked to some of the larger forces of white supremacy.” —Tara Isabella Burton, in Vox.

“Appropriation” is bad. But we have other vocabulary for such cases: “imitation,” “borrowing,” “exchange,” “influence,” “confluence,” “mashup,” even “admiration.”

No culture is pure and free of influence, nor is purity desirable. Just for example, the word “Hinduism” derives from Greek. Traveling from the Mediterranean to explore or conquer the subcontinent, Greeks had to cross the River Indus, which defined India and its many systems of belief for the them. Later, similar words and meanings suited Arab and Western European imperialists who also arrived from the same direction. “India” and “Hindu” were then creatively appropriated by South Asians to promote religious unity from the immense diversity of the region. Thus to say that yoga is an appropriation of Hinduism is to use a European concept that Indians have powerfully appropriated for their own purposes.

I’m not suggesting that there is no problem with cultural appropriation: just that we need a sophisticated apparatus for distinguishing appropriation from other forms of interaction that we should celebrate.

One issue is respect. If you imitate a practice or aesthetic from somewhere else, do you demonstrate appropriate respect for the people who originated it? Are you making fun of them and treating their work as easy? Or are you striving to appreciate its excellence? (By the way, respect is not always merited; there is also room for satire.)

Another issue is quality. In borrowing a cultural product, are you making something excellent or are you cheapening the original? That judgment involves some subjectivity, but there are clearly wonderful examples of cultural imitation–and very poor ones.

And a third issue is the right of ownership. To “appropriate” often means to profit from something that should not be yours. If, for example, a group of people have been using a medicinal herb for centuries until a pharmaceutical company learns of its benefits and patents the compound, I would say that their intellectual property has been appropriated. Although intellectual property is a social construct (not a law of nature), the indigenous people get a raw deal in such cases. Likewise, if Western yoga somehow supports the economic exploitation of South Asians, that is bad. But this is a causal thesis that needs evidence. When a community converts to Christianity, they are not “appropriating Western culture,” and they owe nothing to the West (although some missionaries have thought that they do). Who owes what to whom depends on the context of power.

A deeper question is: What is a culture, anyway? And to whom does any culture belong?

Per the Oxford English Dictionary, “culture” can now be a “count noun,” a noun that makes sense in the plural. In that form, it means “the distinctive ideas, customs, social behaviour, products, or way of life of a particular nation, society, people, or period. Hence: a society or group characterized by such customs, etc.”

This usage is not old. It is first attested in English in 1860, and since then, related uses have emerged, such as contact among cultures (since 1892), the idea of cultural gaps or boundaries (since 1921), culture clashes (since 1926), and the culture of an organization (since 1940).

These uses reflect a profound shift in the way English-speakers see the human world. For many centuries in Europe, it was assumed that there was one best way to do the most important things in life. A good building should have pointed arches and stained glass in 1400, baroque ornaments in 1700. “Culture” was not a count noun: there were not many cultures.

The word had originated in the middle ages with agricultural meanings, but it evolved to mean the cultivation of the mind or spirit–e.g., Sir Thomas More in 1510: “to the culture & profitt of their myndis”–and then a state of refinement. In 1703: “Men of any tolerable Culture and Civility must needs abhor the entering of any such Compact.” The world was divided between those who had Culture and those who did not.

To be sure, some authors, such as Herodotus and Montaigne, were fascinated by the diversity of human customs and beliefs. Still, to be cultured was to do things right, and differences either reflected superficial variations or the unfortunate fact that some people were uncivilized.

However, an alternative theory had emerged in Europe by ca. 1750. On this view, there were many cultures, each reflecting the spirit of a particular people or an age. A person could thus be assigned to a culture as a descriptive category.

I am not qualified to discuss whether other communities across time and space have viewed culture as singular or plural. I suspect that singular views have prevailed in some other places, e.g., in China and Islamic civilization before modernity. In any case, the shifting European theory of culture had global significance because of European colonialism.

One consequence of modern view is a distinction between authentic and borrowed culture. If you are actually English, then to behave like an Indian is inauthentic (and vice-versa). That framework depends on the premise that there are multiple and distinct cultures in the world, and each person really belongs to one.

Another consequence is a marked anxiety about whether we are doing anything right. If there are many cultures, then our cultural norms are local and perhaps arbitrary. Just as Europeans were beginning to understand styles of art and architecture from around the world, they stopped having a normative style of their own. Almost all 19th century European and American architecture is revivalist: it borrows (or “appropriates”) styles from other times and places: Greco-Roman, Byzantine, Gothic, Mughal, and countless others. High modernism is then a revolt against revivalism that seeks new universals–heroically, but without lasting success. And postmodernism is often revived revivalism with a layer of irony.

In this context, it’s important to remember that there are no cultures. Each person has a large set of more-or-less related beliefs, values, and habits that change over her lifetime. The person next door typically shares most but not all of these components. If you examine the components carefully, you’ll find that the come from all over the world and they fit together imperfectly.

A culture is a handy shorthand for this array of components. It’s useful for generalizing about groups of people but always risks overgeneralization. For almost any population, it is possible to draw the cultural boundaries in different places. Nothing they do and believe is completely original or immune to change. Everything is impure–wonderfully so, as a testament to the interconnectedness and avid interactivity of human beings.

Putting up walls and blocking out influences is foolish. But that is not to say that particular acts of borrowing are always respectful, excellent, or fair. When and how to imitate is a hard question for ethical and aesthetic judgment.

See also: when is cultural appropriation good or bad?; cultural mixing and power; Maoist chic as Orientalism; horizon as a metaphor for culture; was Montaigne a relativist?; is a network a good representation of a person’s moral worldview?; are religions comprehensive doctrines?; is society an artifact or an ecosystem?; and avoiding the labels of East and West.

A Randomly Selected Chamber: Promises and Challenges

The 26-page article, A Randomly Selected Chamber: Promises and Challenges (2017), was written by Pierre-Etienne Vandamme and Antione Verret-Hamelin, and published in the Journal of Public Deliberation: Vol. 13: Iss. 1. In the article, the authors discuss the lack of confidence people have in contemporary democracy and hypothethize the hopes and challenges of how a randomly selected chamber of representatives would address this. Read an excerpt of the article below and find the PDF available for download on the Journal of Public Deliberation site here.

From the introduction…

Contemporary democratic representation can be considered to be in crisis as indicated by the fact that many people express mistrust towards the political class in opinion surveys (Norris, 1999; Rosanvallon, 2006). As a consequence, voter turnout to elections is decreasing in most established democracies (Mair, 2013) and party affiliation and identification have become marginal (Dalton & Wattenberg, 2000). We interpret this as the result of two factors: 1) people do not believe that their representatives act in their best interests (problem of representation); and 2) democratic states have lost a lot of regulating power in a globalized economy characterized by capital mobility (problem of scale). We believe that the problem of scale partly explains the crisis of representation, but not entirely. This paper, however, will limit itself to addressing the problem of representation. Consequently, we acknowledge that the proposed solution might not be enough to tackle the identified crisis.

In this paper, we will use the term representation in two distinct senses: “statistical” or “descriptive” representation means mirroring the diversity of the people; “active” representation means acting in the best interests of the people (Pitkin, 1967; Przeworski, Stokes, & Manin, 1999, p. 2). Part of the contemporary crisis of representation stems from the fact that elected representatives are perceived as not acting in the best interests of the people, precisely because they are descriptively different, because they belong to a particular social class with interests of its own. Therefore, their decisions are believed to be biased in favor of this class. A different worry is that elections tend to make representatives neglect some minorities or issues that do not directly affect the interests of their constituency, such as environmental justice.

In reaction to these worries, scholars and activists press for revitalizing or improving contemporary democracies through innovative practices giving a more important role to lay citizens. In the last decades, a plethora of minipublic experiments – randomly selecting participants – have taken place around the world. These democratic experiments are nonetheless marginal in the political landscape: They are usually isolated, temporary, infrequent, brief and depend on elected governments for their organization and macro-political uptake (Goodin, 2008). What is more, because they take place outside the formal sphere of political decisions and limit participation to a happy few, their recommendations lack democratic legitimacy (Lafont, 2015).

Things might be different with a deliberative citizen assembly permanently integrated to our modern democracies, using random selection alongside traditional electoral mechanisms. Here is our concrete proposal. The second chamber of representatives , whose usefulness is now challenged in several countries, should be filled through a random selection among the entire population of the country enjoying political rights. This chamber would exist alongside the elected first chamber, whose prerogatives would remain untouched. The main reason for limiting the use of sortition to the designation of the second (or additional) chamber2 is that elections have some virtues that sortition lacks, in particular the possibilities of universal participation, consent and contestation (Pourtois, 2016)…

Download the full article from the Journal of Public Deliberation here.

About the Journal of Public Deliberation![]()

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen friendly form.

Follow the Deliberative Democracy Consortium on Twitter: @delibdem

Follow the International Association of Public Participation [US] on Twitter: @IAP2USA

Resource Link: www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol13/iss1/art5/

Third Phase Begins for Am. Library Association D&D Training

We are thrilled to announce the third phase of D&D training for librarians is starting in February, as part of our partnership with the American Library Association (ALA) on the Libraries Transforming Communities: Models for Change initiative. Last year we kicked off this partnership to train librarians on D&D methods and processes to share with their communities and further be hubs for engagement and dialogue. The first series last spring was tailored to large/urban public libraries, Fall 2017 was for academic libraries, and this round will be for small, mid-size, and rural public libraries. In addition to the initial webinar NCDD will be doing, this round of trainings will include webinars featuring NCDD member org Future Search and Conversation Café. We encourage you to read the announcement below or find the original on ALA’s site here.

Free Facilitation Training for Small, Mid-Sized and Rural Public Libraries

ALA, the Public Library Association (PLA) and the National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation (NCDD) invite public library staff serving small, mid-sized or rural communities to attend a free learning series on how to lead productive conversations.

ALA, the Public Library Association (PLA) and the National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation (NCDD) invite public library staff serving small, mid-sized or rural communities to attend a free learning series on how to lead productive conversations.

Through Libraries Transforming Communities (LTC): Models for Change, a two-year ALA initiative, library professionals have the opportunity to participate in three online learning sessions and one in-person workshop, all free of charge, between February and June 2018.

“I am excited to begin this process in our community, and I feel better equipped to do so,” said one attendee after a previous LTC: Models for Change learning session.

By attending these sessions, library professionals can learn how to convene critical conversations with people with differing viewpoints; connect more meaningfully with library users and better meet their needs; and translate conversation into action.

Registration is currently open for the following three webinars:

- In Session 1, participants will learn about the range of dialogue and deliberation approaches available; start thinking about their libraries’ engagement goals; learn about resources available to libraries and how to access them; and be introduced to the two dialogue and deliberation approaches that will be featured later in this webinar series. Register for “LTC: Introduction to Dialogue & Deliberation for Public Libraries Serving Small, Mid-sized and/or Rural Communities” (Wednesday, Feb. 28, 1 p.m. CST).

- In Session 2, participants will learn how they can use the Future Search process to enable large, diverse groups to validate a common mission, take responsibility for action, and develop a concrete action plan. Register for “LTC: Future Search” (Wednesday, April 25, 1 p.m. CST).

- In Session 3, participants will learn how Conversation Cafés can help community members learn more about themselves, their community or an issue; essential elements of hosting a Conversation Café; facilitation skills; and techniques for addressing challenges. Register for “LTC: Conversation Café” (Wednesday, May 23, 1 p.m. CST).

Those who view all three webinars, live or recorded, will be invited to attend a free pre-conference workshop exploring the Conversation Café approach in-depth at the 2018 ALA Annual Conference in New Orleans on June 22, 2018. Space is limited, and preference will be given to public library professionals serving small, mid-sized or rural communities.

This learning series is the third offered as part of Libraries Transforming Communities: Models for Change. Previous learning sessions, now available for free viewing, were offered for public libraries serving large or urban communities (recorded spring 2017) and academic libraries (recorded winter 2018).

LTC: Models for Change follows up on Libraries Transforming Communities, a two-year initiative offered in 2014-15 by ALA and The Harwood Institute for Public Innovation that explored and developed the Harwood Institute’s “Turning Outward” approach in public libraries. With this second phase of LTC, ALA broadens its focus on library-led community engagement by offering professional development training in community engagement and dialogue facilitation models created by change-making leaders.

Libraries Transforming Communities: Models for Change is made possible through a grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Laura Bush 21st Century Librarian Program. The initiative is offered by ALA’s Public Programs Office.

You can find the original version of this announcement on the ALA’s Programming Librarian site at www.programminglibrarian.org/articles/free-facilitation-training-small-mid-sized-and-rural-public-libraries.

Qualcosa di nuovo dal fronte occidentale – coesione sociale a Pavia Ovest [Something new on the Western Front - Social cohesion in West Pavia]

Switch. Riuso di spazi in abbandono. Nuove idee per cambiare prospettiva [Switch. Reusing abandoned places. New ideas to change perspectives]

pseudoscience and the No True Scotsman fallacy

I’m sure the point has been made before, but it occurs to me that to describe shameful episodes like racial eugenics as “pseudoscience” risks the “No True Scotsman” fallacy.

This is an early (possibly the first) telling of the No True Scotsman story, by Anthony Flew:

Imagine Hamish McDonald, a Scotsman, sitting down with his Glasgow Morning Herald and seeing an article about how the “Brighton Sex Maniac Strikes Again”. Hamish is shocked and declares that “No Scotsman would do such a thing.” The next day he sits down to read his Glasgow Morning Herald again; and, this time, finds an article about an Aberdeen man whose brutal actions make the Brighton sex maniac seem almost gentlemanly. This fact shows that Hamish was wrong in his opinion, but is he going to admit this? Not likely. This time he says: “No true Scotsman would do such a thing.”

It would similarly be fallacious to say, “No scientist would claim to assemble evidence for white supremacy. Ah, I see that a whole raft of highly distinguished scientists argued for white supremacy, and a few still do. Well, they are not true scientists.”

If “Racism is pseudoscience” is just a way of saying “racism is false,” then I agree with it. But if it’s meant to imply that the actual practice of science–science as a real human activity–would never support racism, then it’s false. Science did support racism, and that tendency lingers in some quarters. Racist scientists are truly scientists in the sense that they practice that occupation and participate in that social institution. They’re wrong, but that shows that science is susceptible to error–both empirical and moral. It’s not helpful to try to evade the problem by definitional fiat.

See also: is science republican (with a little r)? and is all truth scientific truth?

Talking Leadership with Grad Students

Today I had the honor of having been invited to speak at the University of Kentucky’s Graduate Student Leadership Conference. My talk was called “Democracy and Leadership in Higher Education: A Talk for Graduate Students.” I seconded some of the prior speaker’s remarks, which concerned the value of networking, including online and via social media. One student had expressed her aversion to social media. I explained that at least one wants to have a good Web site, as people do want to look you up some when getting to know you. One avenue that can help are social media profiles, but a good Web site can do wonders too. I would encourage some of the same things. He had said that Facebook isn’t a great medium, but that’s because he was thinking of one’s personal Facebook profile. And obviously he hasn’t read my post about why scholars need Facebook author pages (and since I wrote that piece, my author page following has grown from ~2k to ~141k).

Today I had the honor of having been invited to speak at the University of Kentucky’s Graduate Student Leadership Conference. My talk was called “Democracy and Leadership in Higher Education: A Talk for Graduate Students.” I seconded some of the prior speaker’s remarks, which concerned the value of networking, including online and via social media. One student had expressed her aversion to social media. I explained that at least one wants to have a good Web site, as people do want to look you up some when getting to know you. One avenue that can help are social media profiles, but a good Web site can do wonders too. I would encourage some of the same things. He had said that Facebook isn’t a great medium, but that’s because he was thinking of one’s personal Facebook profile. And obviously he hasn’t read my post about why scholars need Facebook author pages (and since I wrote that piece, my author page following has grown from ~2k to ~141k).

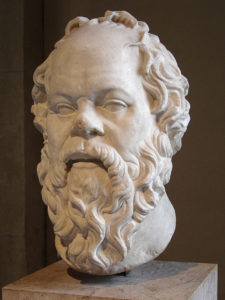

I wasn’t there today to talk about social media, though. Instead, I spoke mainly about my 2013 book, Democracy and Leadership, and showed what I think we still have to learn from Plato, even if it needs updating for the modern and democratic era. I find a lot of value in reminding myself of what Plato’s Socrates says in the first book of the Republic. There, Socrates says that good people won’t be willing to lead. They’d rather others do it. But, some compulsion weighs on good people, inspiring them to be leaders against their inclinations. That compulsion is the fact, in his way of thinking, that worse people will lead. In the democratic era, the language of good people and bad people generally rings as unpleasant at best. My translation for democracy is to say that the compulsion could be instead that good people care about problems, injustices, that could be ameliorated with effort. Good people don’t want to be at the top for its own sake, but accept positions of responsibility because of what would happen if other people would not stand up to address key problems.

I wasn’t there today to talk about social media, though. Instead, I spoke mainly about my 2013 book, Democracy and Leadership, and showed what I think we still have to learn from Plato, even if it needs updating for the modern and democratic era. I find a lot of value in reminding myself of what Plato’s Socrates says in the first book of the Republic. There, Socrates says that good people won’t be willing to lead. They’d rather others do it. But, some compulsion weighs on good people, inspiring them to be leaders against their inclinations. That compulsion is the fact, in his way of thinking, that worse people will lead. In the democratic era, the language of good people and bad people generally rings as unpleasant at best. My translation for democracy is to say that the compulsion could be instead that good people care about problems, injustices, that could be ameliorated with effort. Good people don’t want to be at the top for its own sake, but accept positions of responsibility because of what would happen if other people would not stand up to address key problems.

After that, I explained how and why I think it’s important that we continue to learn about leadership from Plato, even while we disagree with and let go of his authoritarian outlook. In other words, how he characterizes the virtues of leadership is problematic, but there’s no doubt that wisdom is important for leadership, for example, including in the democratic era. It just needs to be understood, pursued, and embodied democratically. So, I talked about what I take that to mean in many contexts of leadership today, but focusing on prime challenges for grad students. After all, good people will need compulsion in grad school too. Leadership is generally thankless, or worse. Plus, it takes a great deal of time and effort, which generally means a distraction from one’s other work. As such, engaging in leadership efforts as a grad student may well mean taking longer to finish one’s program. That’s something serious to accept. To want to lead despite that may well take some compulsion. Even if it does, however, grad student leaders would be wisest if they engage in democratic practices, acknowledging the dangers, challenges, and harms that can come from leading. They should also beware not to carry the world on their shoulders, as time is short, even at its longest, in graduate school (or we generally want it to be), and colleges and universities are slow-moving, relatively conservative institutions. So, at best one can make incremental change and pass on to the next group of leaders their chance to make a further difference.

As such, leadership in the grad school context should stay humble and stoic about what’s possible, want to lead for the right reasons, and be award of the costs, challenges, and reasons not to lead, all while going after it anyway in those cases that truly call for such a sacrifice.

————–

P.S. Of course there was more detail in the talk, but this is the gist of what I had to say this morning, and the people in attendance seemed to appreciate thinking through these matters with me, raising some very thoughtful and valuable questions. My thanks go out to James William Lincoln and the Graduate Student Congress for the invitation.

The post Talking Leadership with Grad Students first appeared on Eric Thomas Weber.