Monthly Archives: May 2017

Graduate Certificate in Collaborative Governance

The Collaborative Governance Graduate certificate is available at Portland State University and is part of the Mark O. Hatfield School of Government. In response to a growing need for collaborative approaches to complex problems that span multiple jurisdictional, sectoral, and organizational boundaries, the Hatfield School of Government, the Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning, the National Policy Consensus Center (NPCC), and the Center for Public Service (CPS) have partnered to offer a set of courses that lead to a Graduate Certificate in Collaborative Governance. Non-certificate students may also opt to take one or more courses individually.

It is our goal to improve the practice of collaborative governance (and therefore governance) by providing students with the following knowledge and skills:

- Define collaborative governance and its value in public policy-making and creation of public goods.

- Identify and exemplify principles of professional responsibilities and ethics in a collaborative setting.

- Design and manage collaborative processes, partnerships, and networks.

- Employ appropriate analysis techniques to understand and monitor collaborative efforts and outcomes, including the identification and application of relevant technical and scientific information.

- Demonstrate leadership, as well as verbal and written communications skills aligned with principles of collaboration.

- Demonstrate an understanding of group dynamics, deliberation, and decision-making by effectively engaging with teams and groups in collaborative contexts.

- Identify and apply appropriate negotiation and conflict management theories and frameworks in two-party, and multi-party settings.

- Employ computer and web-based decision and communications tools in a collaborative context.

The certificate program consists of 16 credit hours of graduate coursework and is intended to provide working professionals and graduate students with the knowledge and skills necessary to successfully lead or engage in collaborative efforts designed to generate and/or implement sustainable solutions. All core courses for the Graduate Certificate in Collaborative Governance are offered on-line. In addition, at least one of the elective courses (PA 577) is offered on-line.

Course of Study

[NCDD note: Below are the current courses for the program as of Spring 2017 and they may be subject to change in the future.]

Core Courses

Students must take the following four core courses:

- PA 575: Foundations of Collaborative Governance (3 credits) – Fall

This initial course provides an overview of the current governing context and the new models that have emerged in response. In addition, students will explore the nature of collaborative relationships, the role of trust, harnessing the potential power of groups, and how to address conflict and reach consensus. - PA 576: Collaborative Governance Process & Systems (3 credits) – Winter

This skills-based course focuses on the assessment, organization and phases of facilitating collaborative agreement-seeking processes, emphasizing techniques and challenges for reaching mutually satisfying agreements, including how to frame an issue to increase the group’s chance for success. - USP 584: Negotiation in the Public Sector (4 credits) – Summer

This course offers an overview of the conventional and innovative applications of negotiations in public sector activities, and the potential and limitations of negotiation-based approaches to public decision making. Key components include negotiation theory, individual skill development and a review of the institutional, legal and political context of negotiations. - PA 578: Collaborative Governance Practicum (3 credits) – Fall

In this culminating practicum, students participate in discussions with faculty experts and fellow students as they apply the knowledge and skills gained in core courses to a community-based problem, issue, or project of their choosing.

Electives

Students must also complete one elective course of their choice. The following is a list of suggested elective courses. Courses not on this list may also be eligible with pre-approval by certificate program faculty.PA 577: Case Studies in Collaborative Governance (3 credits) – Spring

- PA 543: Creating Collaborative Communities (3 credits)

- PA 553: Sustainable Development Policy and Governance (3 credits)

- USP 550: Concepts of Citizen Participation (4 credits)

- USP 619: Development Partnerships (3 credits)

- SYSC 511: Systems Theory (4 credits)

- PA 564: Current Issues in Environmental Policy and Administration (3 credits)

- CR 515: Negotiation and Mediation (4 credits)

- CR 524: Advanced Mediation (4 credits)

- CR 526: Intercultural Conflict Resolution (4 credits)

- CR 512: Perspectives in Conflict Resolution (4 credits)

About PSU’s Hatfield School of Government

Dedicated to public service and social justice, the Hatfield School does more than teach — we prepare students for community leadership and for making the world a better place. Located in the vibrant heart of downtown Portland, the Hatfield School offers real-world application of studies only steps away from the classroom. Students actively engage in a variety of hands-on public service projects throughout Oregon, the nation, and the world.

Resource Link: www.pdx.edu/hatfieldschool/collaborate

This resource was submitted by Sarah Giles, Special Projects Manager at Portland State University’s Hatfield School of Government via the Add-a-Resource form.

Preparing students for civic life

A question that has recently been on my mind as I work on book chapters around helping English language learners with civic learning is the question of teaching for citizenship. Certainly, one of the key goals of the Florida Joint Center for Citizenship is preparing students to be citizens. It is, after all, in our name. But on reflection, perhaps we should consider that we are going deeper than that. We are, instead, preparing students for civic life. Not all of the students we seek to reach are citizens, after all. At the same time, the knowledge, skills, and dispositions we want children to develop should be practiced long before they are able to assume the rights and duties of citizenship anyway. Key here is the idea that civic life is more than simply voting or serving on juries, both of which are rightly and justly limited to citizens of the United States. But what does it mean to prepare students for civic life, to truly help them understand what it means to engage in their communities and to seek to be a difference-maker?

Before we begin considering that question, it needs to be stated plainly that what we are discussing here is a not a question of liberal or conservative. Instead, it is a question of doing what you think is right and necessary for the civic life of your community. Civic life should not be centered around partisan warfare; rather, it should be centered around true discussion, collaboration, and the common good as our Founding Fathers understood it. As one of my personal heroes, John Adams, so eloquently put it in the Constitution of the great state of Massachusetts:

Government is instituted for the common good; for the protection, safety, prosperity and happiness of the people; and not for the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men: Therefore the people alone have an incontestable, unalienable, and indefeasible right to institute government; and to reform, alter, or totally change the same, when their protection, safety, prosperity and happiness require it.

So, in preparing students for civic life, what should we be addressing? The Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools has suggested that the focus be on civic competencies that have stood the test of time and reflect the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for civic life in the 21st century United States of America. Today’s post will discuss the first competency, knowledge; later posts will dive into the skills and dispositions, the Six Proven Practices, and the new(ish) C3 FrameworkC3 Framework and how that might serve us as civic educators.

Civic Knowledge: Starting With a Foundation

You have to start somewhere. For us, civic life must be built on a foundation that reflects what came before. You cannot engage in civic life and the pursuit of the common good if you have no or little knowledge of history, civics, and government. The Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools describes the competency of civic knowledge thus:

Civic content includes both core knowledge and the ability to apply knowledge to different circumstances and settings.

- Key historical periods, episodes, cases, themes, and experiences of individuals and groups in U.S. history

- Principles, documents, and ideas essential to constitutional democracy

- Relationship between historical documents, principles, and episodes and contemporary issues

- Structures, processes, and functions of government; powers of branches and levels of government

- Political vehicles for representing public opinion and effecting political change

- Mechanisms and structure of the U.S. legal system

- Relationship between government and other sectors

- Political and civic heroes

- Social and political networks for making change

- Social movements and struggles, particularly those that address issues as yet unresolved

- Structural analyses of social problems and systemic solutions to making change

In other words, to effectively participate civic life, we must have an understanding of what came before. It means understanding the decisions that our Founding Fathers made, and the roots and consequences of those decisions. Why, for example, did they decide on the Electoral College? How did the party system develop? What kinds of issues have those seeking to lead, organize, or participate in civic life had to deal with over the course of our two and a half century history?

It also requires that we be able to interpret the key documents that have shaped civic life and civil society in the United States. This includes the Magna Carta, the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Declaration of Independence, the later amendments to the Constitution, and even the Articles of Confederation (among so many others). Important within this understanding is being able to grasp the different ways these documents have been interpreted in the past and continue to be debated in the present. For example, what do we mean when we say and debate the idea that Constitution is a living document? At the same time, we cannot know our rights, truly know and practice our rights, unless we understand them. And that rights are balanced by responsibilities and the importance of civic virtue and the common good.

To participate in civic life, we also need to understand how government works and how to take part in that government. This is more than simply voting; this is active engagement with fellow citizens and leaders in order to pursue change using the processes of government. And, again, we need note have a partisan perspective on this. The Tea Party movement of the previous decade is one form; the civil rights marches of the past century are another. Both seek to influence the levers and powers of government to pursue political, economic, or social change. But to do so effectively, we must help our students understand how government works and what influences government to take, or not take, action.

The idea of heroes, as presented in the list proposed by the Campaign, is to me a bit problematic and can lead to rather contentious debate. What do we mean by ‘political and civic heroes’? One person’s hero may be another person’s villain (as we see in the contentious debate over Confederate monuments). That does not mean, however, that this is a discussion to avoid. Indeed, we may find this debate a way in which we can model for our students the ways in which disagreements should be approach in a healthy civic culture. Whatever the choice we make, our heroes should reflect the types of engagement we want our children to have in civic life.

For me, most importantly, helping our students understand that engaging in civic life CAN make a difference is key. What networks can we form, what understandings can we refine, in order engage in civic life and pursue the common good?

Knowledge Matters

To me, without the competency of civic knowledge, the skills and dispositions are, to some great degree, worthless. If you lack understanding, how can you collaborate to make change? How can you engage in civic life? This does not serve as a call for rote memorization or some multiple choice test; rather, we need to teach our students how to find the information they need, how they may use the skills they have to interpret it, and, reflecting the desires of folks like Benjamin Rush, Thomas Jefferson, Noah Webster, and later Horace Mann, a common understanding and body of knowledge that is shared among all participants in civic life.

In a later post, we will take a look at the skills that can take advantage of this knowledge.

mini-conference on Facts, Values, and Strategies

We are about to begin discussions of the papers listed below, in draft form. They are destined for The Good Society journal. The conversations are at the Tisch College of Civic Life at Tufts

For me, the underlying rationale goes like this. A good person is always asking “What should I do?” That question must become plural–“What should we do?”–for two reasons: we cannot accomplish enough alone, and we must reason together to improve our opinions. Both questions integrate facts and values. Something that works but isn’t good is not what we should do. Likewise, we want to avoid something that is good but doesn’t fit the circumstances of the time and place.

The structure of intellectual life in modernity frustrates asking these questions, for several reasons. One major reason is that matters of value are assigned to certain disciplines in the humanities, while matters of fact go to disciplines that widely imitate science and present themselves as value-free.

It’s easy to call for a reintegration of facts and values (and strategy), but very hard to pull that off. Fortunately, we have traditions of thought–always contributed by many thinkers and practitioners rather than a single luminary–that do reintegrate facts, values, and strategies. Names that stand for these traditions include Gandhi, Pope Francis, Hannah Arendt, William James, Amartya Sen, Elinor Ostrom, and Jurgen Habermas. These names recur in interesting combinations in the following papers. So do certain themes: the limitations of human cognitive abilities and the positive potential of certain kinds of affect; the value of institutions for structuring deliberation; the link between work and reflection; and the value of deep, responsive uncertainty–wonder.

“Public Entrepreneurship, Civic Competence, and Voluntary Association: Self-Governance Through the Ostroms’ Political Economy Lenses” — Paul Dragos Aligica, George Mason University

“Giving Birth in the Public Square: Dialogue as a Maieutic Practice” — Lauren Swayne Barthold, Endicott College and Essential Partners

“William James’s Psychology of Philosophizing: Selective Attention, Intellectual Diversity, and the Sentiments in Our Rationalities” — Paul Croce, Stetson University

“Democracy as Group Discussion and Collective Action:Facts, Values, and Strategies in Rural Landscapes” — Timothy J. Shaffer, Kansas State University

“Social Media, Dismantling Racism and Mystical Knowing: What White Catholics are Learning from #BlackLivesMatter” — Mary E. Hess, University of Toronto

“Institutions, Capabilities, Citizens” — James Johnson, University of Rochester, and Susan Orr, SUNY College at Brockport

“Forgiveness After Charleston: The Ethics of an Unlikely Act” — Larry M. Jorgensen, Skidmore College

“Facts, Values, and Democracy Worth Wanting: Public Deliberation in the Era of Trump” — David Eric Meens, University of Colorado Boulder

“The Praxis of Amartya Sen and the Promotion of Democratic Capability” — Anthony DeCesare, St. Louis University

“A Civic Account of Justice” — Karol Edward Soltan, University of Maryland

Facts/Values/Strategies Conference

I will offline tomorrow, attending the Facts/Values/Strategies mini-conference co-hosted by Tufts’ University’s Tisch College of Civic Life and The Good Society, the journal of civic studies for which I serve as an editor.

In preparation for this conference, I’ve been reading the conference papers – which each seek to integrate facts, values, and strategies in conceiving of citizen’s roles in civil society. The papers have been engaging and inspiring, and I’m looking forward to a day and a half of dialogue digging into these topics.

The framing statement for the conference is below:

Current global crises of democracy raise fundamental questions about how citizens can be responsible and effective actors, whether they are combating racism in the United States, protecting human rights in the Middle East, or addressing climate change. If “citizens” are people who strive to leave their communities greater and more beautiful (as in the Athenian citizen’s oath), then their thinking must combine facts, values, and strategies, because all three must influence any wise decision. Mainstream scholarship distinguishes facts, values, and strategies, assigning them to different branches of the academy. Many critics have noted the philosophical shortcomings of the fact/value distinction, but citizens need accounts of how facts, values, and strategies can be recombined, both in theory and in practice. John Dewey, Hannah Arendt, Mahatma Gandhi, Jürgen Habermas, Amartya Sen—and many other theorists of citizenship—have offered such accounts.

Actual civic movements also combine facts, values, and strategies in distinctive ways. For instance, the American Civil Rights Movement used the language of prophesy, and Second Wave Feminism strategically advocated new ways of knowing.

These papers propose theoretical, methodological, historical, and empirical responses and case-studies related to the question: how should citizens put facts, values, and strategies together?

Navigating a Polarized Landscape with Our Nonpartisan Credentials Intact

In the post-2016 election landscape where talk of “threats to democracy” abounds, many organizations focused on deliberative democracy and public engagement, including NCDD, have had to relearn not only how to balance participating in public conversation about issues that didn’t used to seem partisan before, but how to do so while maintaining our nonpartisan stances and not violating our organizational or personal values. It’s not easy, which is why we appreciated NCDD member org Healthy Democracy‘s recent piece that offers solid advice for how to evaluate and maintain our nonpartisan nature in this fraught new environment. We highly recommend you read their piece below or find the original here.

Nonpartisan Hygiene: 6 Tips to Stay Squeaky Clean

We find ourselves in a political moment where significant sectors of the country warn of existential threats to our democracy. This began before the 2016 election, but it has since reached a fever pitch. Signals such as the Economist Intelligence Unit’s recent “downgrade” of the US from a “full democracy” to a “flawed democracy” have added fuel to the fire. At Healthy Democracy, we do not take a position about whether these threats are real or not, though we spend a great deal of time trying to improve our democracy.

We find ourselves in a political moment where significant sectors of the country warn of existential threats to our democracy. This began before the 2016 election, but it has since reached a fever pitch. Signals such as the Economist Intelligence Unit’s recent “downgrade” of the US from a “full democracy” to a “flawed democracy” have added fuel to the fire. At Healthy Democracy, we do not take a position about whether these threats are real or not, though we spend a great deal of time trying to improve our democracy.

Nonpartisan “Positions”

As a nonpartisan organization, we cannot take a position that would turn off members of any political or demographic group. This is because we rely on our reputation as unbiased process experts when working with citizens from across the political spectrum. Additionally, we don’t take positions on issues that might come before a Citizens Initiative Review panel, including the proposals of our peers in the elections reform space.

In some ways, this makes it easy for us to choose the issues on which we take a public position (pretty much nothing), but when “threats to our democracy” come up, and considering our name is Healthy Democracy, what do we do? Do we retweet a statement praising a free press? Or is publicly expressing support for a free press now viewed as a partisan act?

We can make these decisions ad hoc, but we risk inconsistency, or worse: letting our personal perspectives and biases sway our decisions. We realized that Healthy Democracy needed to do some thinking. Some nonpartisan hygiene, if you will, to get our internal activities and the external communication of our work squarely in our nonpartisan ethos.

As a result of our analysis, we humbly share some “nonpartisan hygiene” tips that may come in handy to other organizations in this space, including bipartisan political organizations, nonpartisan think tanks, newsrooms, and professional organizations. Government scientists and policy thinkers may find this helpful, as well. This is written with nonpartisan nonprofits in mind, but please take from it anything that is helpful to your organization’s needs.

What we lose when we’re not scrupulously nonpartisan

There is an idea that floats around nonpartisan and social good organizations that we have “nonpartisan capital” that builds up when an organization is nonpartisan for a long time. The theory goes that we can spend this capital in little bits when it’s worth it, for example when a politician does something particularly egregious, or when a policy is implemented that violates our ethics. I speculate that this thinking is dangerous and flawed. Being nonpartisan is an all-or-nothing proposition when it comes to public perception. This is part of why nonpartisan spaces are precious and scarce.

Additionally, that perceived “nonpartisan capital” should not be mistaken for influence or power. Even if we accept the idea of nonpartisan capital, we cannot reliably mete it out, spending only enough to “make a difference” without trashing our reputation. In fact, we risk throwing away our most precious resource if we view it, incorrectly, as something can be given away in metered chunks.

6 Tips to Stay Squeaky Clean and Effective

1. Reassess your internal and external values. Most nonprofits have a set of values articulated in their strategic plan. These are typically things like transparency, service, and inclusion. Often, these are internal values about how the organization runs itself, or they are a mix of internal and external values. Take transparency, for instance. This is a laudable internal value, and many nonpartisan nonprofits list it among their core values. But if a politician or public figure does something that violates that value, should the organization publicly condemn it? Probably only if transparency is a core external value, such as the fictional nonpartisan group, Americans for Transparent Government.

Do the same exercise with service and inclusion and you can see how this can get tricky if you don’t have a clear sense of your organization’s internal versus external values. Spend some time clarifying internal and external values in a board meeting, retreat, staff meeting, or chat. If you are starting from scratch naming external values, start with your mission and think about what you need to do to keep credibility in your space. Your communications team should be well-apprised of these values, since they are on the front lines of selecting the media with which the organization affiliates and interacts.

2. Shore up your nonpartisan bonafides among your staff, board, and partners. The simplest way to get nonpartisan credibility is to have actual political diversity on your staff, even if you don’t publicly identify your political affiliations. Not only will this increase your organization’s credibility, it will make you better at your work.

If you have trouble attracting staff from one side of political spectrum, examine that! If you can’t easily hire to bring more political diversity onto your staff, consider affiliating with a thoughtful person who brings a different political orientation and is willing to consult now and again. If you have a question about whether a particular activity or position would be viewed as overtly partisan, get their take on it. This can reveal blind spots and save your bacon. And there is really no reason not to have a board that reflects political – and other – diversity.

3. Play out scenarios, both commonplace and extreme. In your retreat, staff meeting, or chat, start with your external values and play out some scenarios that would challenge them. Consider everything from the commonplace (“Should we retweet this?”) to the extreme (“What if we were asked to do our program on a policy that offends our values?”). In our version of this conversation, we asked ourselves whether we would agree to deliver a Citizens’ Initiative Review on a fictional ballot measure. The fictional measure would require members of a particular religious faith to register with the state government. This kind of policy deeply offends our personal values, and would be an “extreme” scenario.

We talked through the pitfalls: would our participation lend legitimacy to an unconscionable policy? Would we run the risk of becoming tainted by affiliating ourselves with the public conversation about the measure? We decided, somewhat to our surprise, that we would do it; we would deliver a citizen review of the measure. But only if we were sure it could be done in a fair and unbiased way, as with every measure we review. The legitimacy question is moot; the measure is already on the fictional ballot. Our participation would simply allow the voters of that state to shine a light on the measure, and that’s a good thing. You really have to believe in your programs in a case like this. Thankfully, we do.

4. Invite external evaluations of partisanship and effectiveness. Be transparent about the results, and make changes in response to critical feedback. Take advantage of university researchers who will fund themselves to research your work! Think of this like ripping off a band-aid. If you get spotless evaluations the first time, great, but you probably won’t. Be transparent about your efforts to improve non-partisanship and you’ll reap greater effectiveness and rewards.

We’re proud that every Citizens’ Initiative Review has been evaluated by independent university researchers, and we owe a great deal our credibility as a deliverer of fair and unbiased processes to those evaluation results. This is worth its weight in gold. If you can’t find a university researcher, at least partner occasionally with an external auditor of your programs to shore up your internal evaluation methods and get a reality check on how well you’re doing.

5. Be uncompromising in your affiliations. Hold partners to a high standard of nonpartisanship and rigor. If your work calls for you to affiliate with partisan groups, seek a balance. Don’t work with anyone who doesn’t evaluate their work, or who misrepresents themselves as nonpartisan when they’re not scrupulously so.

6. Hold the nonpartisan space. Nonpartisan spaces are scarce and valuable. There are many actors in the advocacy space. Let them do their jobs, and let us do ours.

You can find the original version of this Healthy Democracy blog piece at www.healthydemocracy.org/blog/nonpartisan.

Let’s Talk Numbers: Americans Want Price Transparency and Cost Conversations

American tapestry

6:10 am, Monday, Boston, MA: My taxi driver is a retired guy from the South Shore. His son is a Ranger, active duty. The son curls up on the floor now when fireworks go off: PTSD. He is friends with all the generals, ever since he use a banned weapon in Afghanistan to save some guys despite the orders of an interfering German NATO officer. According to him, the US generals believe we have to stop fighting all these little wars, because then the media turns every bit of collateral damage into a war crime. We need one big war to just end it.

3:30 pm, Monday, Ferguson, MO: I am getting a detailed and extraordinarily well-informed and thoughtful driving tour through this city, traversing all the main roads plus several of the back streets and cul-de-sacs. My guide, an African American woman and longtime resident of Ferguson, is also a scholar with a PhD, an educator, and an activist. Through her windshield, Ferguson looks remarkably ordinary: Anywhere, USA. Sam’s Club, Walmart, mowed median strips, the Interstate, tidy homes of brick or wood, low-rise apartment complexes, some fancy older houses along one side of town, and knots of happy kids walking home from their schools. It is Anywhere, USA–which is the problem.

7:30 pm, Monday, Kansas City, MO: Sitting at the bar of a BBQ restaurant that caters to tourists, with baseball on the TV screens and the news on my smartphone that the President of the United States has casually divulged secret information to the Russian ambassador.

Isotta Nogarola

Isotta Nogarola was a great one of the great female humanists of the Renaissance.

Born to a wealthy family in Verona, Nogarola was trained in the humanist arts – as was the custom for aristocratic men and women of the day.

Women, however, were expected to do little with their training but be personally enriched to that they may later similarly enrich their own children.

Nogarola, however, sought to further enrich the humanist field by entering into scholarly correspondence with some of the leading humanists in Italy.

Her letters drew scorn from the greater public. There is a long history in the Western world of women being excluded from the public sphere; of being silenced and branded as unclean if they dare speak up.

Nogarola was no exception – rumors spread that she was a prostitute, and that she had engaged in incest.

The reasoning for these rumors?

An eloquent women is never chaste.

A New Primer on the Commons & P2P

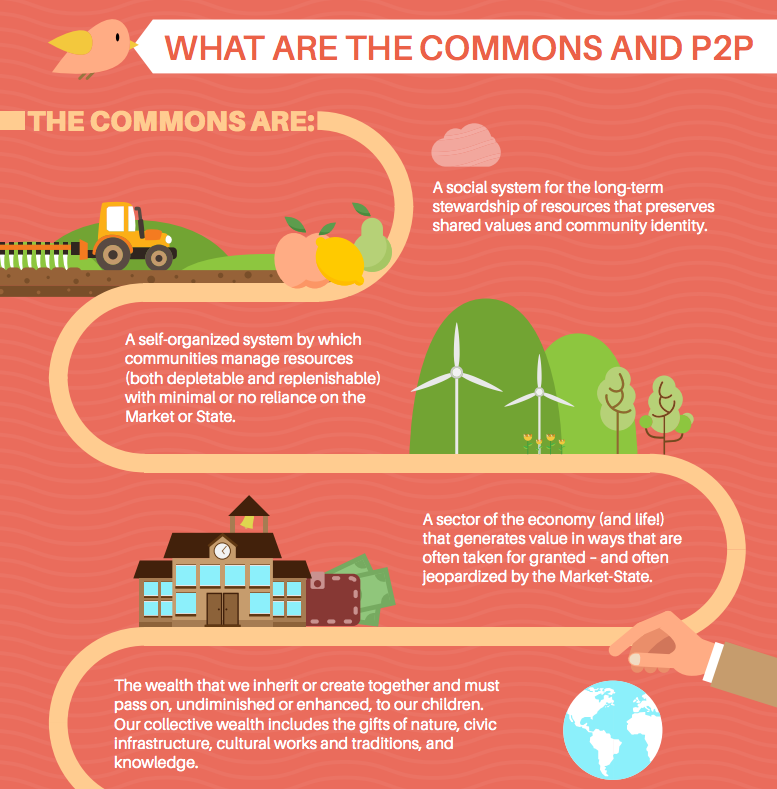

Most readers of this blog don’t need an introduction the commons, but there are always newcomers for whom a short overview would be useful. The Transnational Institute and the P2P Foundation have done just that with an attractive new publication “Commons Transition and P2P: A Primer.”

The beautifully designed fifty-page booklet does not dumb down the topic; it simply makes some of the complexities associated with commons and peer production more accessible to the general reader in a single document. The primer explains the basics of commons and peer-to-peer production (P2P), how they interrelate, their movements and trends, and "how a Commons transition is poised to reinvigorate work, politics, production, and care, both interpersonal and environmental.”

A short video about the primer can be watched here. It explains that "the commons are a self-organized system by which local communities manage shared resources with minimal or no reliance on the market or the state. P2P means collaboration, ‘peer-to-peer’, ‘people-to-people’ or ‘person-to-person.’ P2P is a type of non-hierarchical and non-coercive social relations that enables a transition to a fairer economy for people and nature.”

Besides introducing the commons & P2P, the booklet suggests five practical guidelines, with examples, for achieving a transition to a commons/P2P-based society:

1. Pool resources wherever possible;

2. Introduce reciprocity;

3. Shift from redistribution to predistribution and empowermernt;

4. Subordinate capitalism; and

5. Organize at the local and global levels.

Michel Bauwens, founder of the P2P Foundation, notes that because previous social revolutions have not always succeeded so well,

“what matters is the reconstruction of prefigurative value-creating production systems first, to make peer production an autonomous and full mode of production which can sustain itself and its contributors; and the reconstruction of social and political power which is associated and informed by this new social configuration.

The organic events will unfold with or without these forces, ready or not, but if we’re not ready, the human cost might be very steep. Therefore the motto should be: contribute to the phase transition first; and be ready for the coming sparks and organic events that will require the mobilization of all.”

Kudos to Michel Bauwens, Vasilis Kostakis, Stacco Troncoso and Ann Marie Utratel for the text of the primer as well to designer Elena Martínez for its attractive look.