While graph theory has a long and rich history as a field of mathematics, it is only relatively recently that these concepts have found their way into the social sciences and other disciplines.

In 1967, Stanley Milgram published his work on The Small World Problem. In 1973 Mark Granovetter studied The Strength of Weak Ties. But while this applied methodology is young, the interest in networks has been in the ether of political theory for some time.

I’ve noted previously how Walter Lippmann can be interpreted as invoking networks in his 1925 book the Phantom Public. Lippmann argues vehemently against this thing we call ‘public opinion’ – a myth Lippmann doesn’t believe truly exists:

We have been taught to think of society as a body, with a mind, a soul, and a purpose, not as a collection of men, women and children whose minds, souls and purposes are variously related. Instead of being allowed to think realistically of a complex of social relations, we have had foisted upon us by various great propagative movements the notion of a mythical entity, called Society, the Nation, the Community.

Rather than thinking of society as a single, collective whole, Lippmann argues that we ought to “think of society not as the name of a thing but as the name of all the adjustments between individuals and their things.”

I’d noted this passage in Lippmann when I first read his work several year ago. But I was surprised recently to come across a similarly networked-oriented sentiment in John Dewey’s 1927 rebuttal, The Public and Its Problems:

In its approximate sense, anything is individual which moves and acts as a unitary thing. For common sense, a certain spatial separateness is the mark of this individuality. A thing is one when it stands, lies or moves as a unit independently of other things, whether it be a stone, tree, molecule or drop of water, or a human being. But even vulgar common sense at once introduces certain qualifications. The tree stands only when rooted in soil; it lives or dies in the mode of its connections with sunlight, air and water. Then too the tree is a collection if interacting parts; is the tree more a single whole than it’s cells?

…From another point of view, we have to qualify our approximate notion of an individual as being that which acts and moves as a unitary thing. We have to consider not only its connections and ties, but the consequences with respect to which it acts and moves. We are compelled to say that for some purposes, for some results, the tree is an individual, for others the cell, and for a third, the forest or the landscape…an individual, whatever else it is or is not, is not just the specially isolated thing our imagination inclines to take it to be.

…Any human being is in one respect an association, consisting of a multitude of cells each living its own life. And as the activity of each cell is conditioned and directed by those with which it interacts, so the human being whom we fasten upon as individual par excellence is moved and regulated by his association with others; what he does and what the consequences of his behavior are, what his experience consists of, cannot even be described, much less accounted for, in isolation.

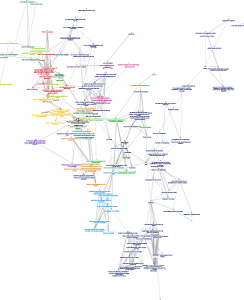

I like to ask people to state their own beliefs that are relevant to ethics and then draw connections among those ideas to create networks that represent their moral worldviews. I put people (students and others) in dialogue with each other, invite them to explain their networks to peers, and watch connections form.

I like to ask people to state their own beliefs that are relevant to ethics and then draw connections among those ideas to create networks that represent their moral worldviews. I put people (students and others) in dialogue with each other, invite them to explain their networks to peers, and watch connections form.