Monthly Archives: February 2016

Citizen Professionals as Democratic Patriots

I agree with her idea of "democratic habits" as the goal of education. I'd also bring in the skills and habits of civic agency. A topic for another day: how to assess civic agency?

Her emphasis on "habits of mind and heart" is a lot better than the simple cognitive focus on "mind" in higher education which dominates these days.

Richard Levin, president Emeritus of Yale, gave a talk last fall at the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign where I'm going tomorrow. His title was "education for global citizenship." He made interesting points about the need to revisit older ideas about what are "furniture" and the "disciplines" of the mind, drawing on Yale curricular changes. But Levin neglected "heart," the way education cultivates affections. He also neglected "hand," work in the world. I am glad Meier also mentioned developing work habits, like being mutually accountable, as part of the purpose.

There is a growing sense of crisis among educators in higher education that we've lost control over the huge changes occurring (there also seems to a feeling of loss of agency in K-12 but it takes somewhat different forms). Colleges and universities face rising costs, growing student debt, political attacks, and technological transformations. Educators usually feel powerless.

Emphasizing (and assessing) democratic habits of civic agency is not only good for students but also good for educators. Faculty and staff need skills and habits of democratic action and reflection to move from being objects and victims of change to being agents and architects of change.

Here are two "polarities" which disempower higher education's educators by greatly weakening relationships with larger publics and the world outside higher education. One is the tension between "education for global citizenship," widely advanced as the aim of liberal education, and inward-looking nationalism. Reflecting the culture of detachment in research I described last week, educators tend to see themselves as "outside" the society, partnering with citizens -- not as citizens themselves.

The other is the tension between preparation for careers and liberal education.

Adding heart and hand involves two ways to rethink things. In the civil rights movement I learned "democratic internationalism," different than either "America 1st" nationalism or global citizenship.

I worked for the Citizenship Education Program of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, King's organization. Our "Citizenship Workbook" put it this way. "We love our land - America!" It also affirmed the right of other peoples in the Western Hemisphere to the identity of "American." And it welcomed the emergence of new nations in Africa and Asia "where people of color are demanding the freedom to decide their destiny."

Democratic internationalism challenges distinctions between "advanced" democracies and "emerging" democracies. In a time of grave threats to democracy in the US and across the world, we need to learn from each other.

Democratic internationalism is grounded in patriotism which sees citizens not defined by legal status but rather by citizens as co-creators of open and dynamic societies, refreshed by each wave of immigrants and new generations. We need to love our society, warts and all, and its great democratic possibilities.

The culture of being "outside" has spread to all the professions. Professionals who talk about civic engagement see it as meaning working with citizens. They don't see themselves as citizens. Adding "hand" to heart and mind brings together liberal arts together with career preparation.

This means new focus on "citizen professional" (and "citizen worker") in many fields, graduates who understand and engage the world as it is but also are effective agents of change, who see institutions not as places to fit in but rather as sites for democratic transformation.

Citizen professional schooling requires equipping students and educators with capacities to create empowering schools and businesses, congregations and clinics, nonprofits and public agencies -- foundations for democracy as a way of life not simply a trip to the ballot box.

Shouldn't a democratic, open patriotism and civic agency begin in K-12 schools? And shouldn't K-12 schools make strong connections between learning and work with public purpose and impact?

The tag line of the Minneapolis public schools is "education for global citizenship."

I'm sure it's meant to welcome new immigrants. But my experience is that like most African Americans in the civil rights movement, immigrants "love our land - America!"

They also want to be co-creators, builders of democracy as a way of life.

Citizen Professionals as Democratic Patriots

Citizen Professionals as Democratic Patriots

Frontiers of Democracy 2016

Registration has just opened for Frontiers of Democracy 2016.

Hosted by my former colleagues at Tufts University’s Jonathan M. Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service, Frontiers annually brings together a diverse group of scholars and practitioners to discuss timely issues in the civic field.

This gathering, which will take place in Boston June 23 – 25, is one of the highlights of my year as people from a range of disciplines come together to share insights, questions, ideas, and advice.

(In full disclosure, I am totally biased in this view as I have done some work helping to organize this conference over the years.)

This year’s conference will focus on “the politics of discontent,” which is define broadly and view in a global perspective. The organizing team is still accepting proposals for interactive “learning exchanges,” which can be submitted online here: http://tinyurl.com/zxy5jph.

Special guest speakers this year include:

- Danielle Allen, Harvard University, author of Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality (2014)

- Laura Grattan, Wellesley College, author of Populism’s Power: Radical Grassroots Democracy in America (2016)

- Joseph Hoereth, Director of the Institute for Policy and Civic Engagement at the University of Illinois at Chicago

- Helen Landemore, Yale University, author of Democratic Reason: Politics, Collective Intelligence, and the Rule of the Many (2012)

- Talmon J. Smith, Tufts ’16, a Huffington Post columnist on political reform

- Victor Yang, an organizer for the SEIU

Register here and I hope to see you in June!

why don’t young people like parties?

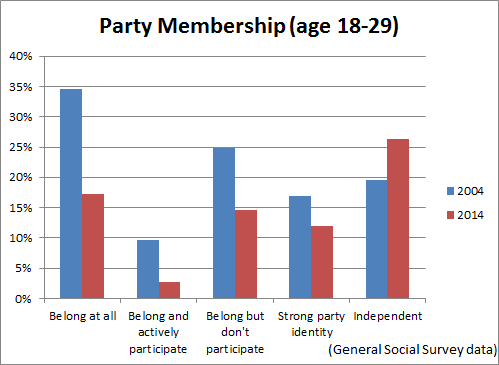

Young Americans are not very loyal to parties. Many young people hold political beliefs that may make them almost guaranteed to vote for one party rather than the other–true “swing” voters are very rare–but they don’t identify with parties as organizations or devote their energy to parties as opposed to candidates and causes. I think that is partly why young people have so far been happy to vote for Bernie Sanders over Hillary Clinton by 4:1 margins. Remember that the primary election process was set up to allow party members to choose their party’s nominee, but young people who vote in the Democratic primaries don’t blink an eye to support a candidate who has chosen not to be a Democrat during his political career. I am not saying they should behave differently; I just think it’s interesting.

I have often heard cultural/generational explanations of this trend. Supposedly, Millennials are less favorable to organizations of all kinds. They prefer and expect looser and less hierarchical networks. There may be some truth to that, but I would suggest a different hypothesis. Young people are less loyal to parties than their predecessors were because parties don’t do anything any more.

Parties used to have functions, such as recruiting volunteers, paying workers, and organizing events (not to mention controlling patronage). Parties are now labels for clusters of entrepreneurial candidates and interest groups. The change occurred because the campaign finance reforms of the early 1970s defunded the parties, and then the deregulation of the 2000s allowed vast amounts of money to flow to entities other than parties. The Koch Brothers’ political network, for instance, employs 3.5 times as many people as the Republican National Committee does.

If parties do nothing for or with young people, it is easy to explain why youth don’t care about parties.

The General Social Survey asks about partisan ID at least every other year. The proportion of younger people who are Independents has grown, but most political scientists argue that that trend is misleading since the number of undecided or swing voters has actually shrunk. More to the point are questions that the GSS has asked only twice, about membership and active participation in parties. We know that parties didn’t do much to engage youth in 2004, because Dan Shea surveyed local party leaders that year, and “Only a handful of [county] party chairs mentioned what we might call significant activities, programs that require a significant amount of time or resources.” The parties were already hollow compared to decades earlier. He also asked an open-ended question: “Are there demographic groups of voters that are currently important to the long term success of your local party?” Just eight percent named young voters.

Nevertheless, the GSS indicates that the proportion of youth who actively participated in parties was 3.6 times higher in 2004 than it was in 2014. The hollowing-out continues.

Save the Date: NCDD 2016 is set for Oct 14-16 in Boston!

It’s time to mark your calendars for the highly anticipated 2016 National Conference on Dialogue & Deliberation! We’re excited to announce that our next national conference will take place in the Boston area this October 14-16.

Our conferences only come around every two years, and you won’t want to miss this one! Just last night, someone told me they’ve never had more fun at a conference than at the last NCDD conference. But NCDD conferences aren’t just about having fun and enjoying the company of our field’s movers and shakers. They’re about forming new partnerships, strategizing together about how we can tackle our field’s greatest challenges, showcasing some of the coolest arts, technologies, and methods for public engagement — and so much more.

If you haven’t attended an NCDD conference yet, watch our highlight video by Keith Harrington of Shoestring Videos to get a sense of the energy and content of the last national conference…

We can’t wait to see you this October! I’m particularly looking forward to holding a conference in my new backyard (yay Boston!), and working closely with our local planning team. We’ll be holding the conference at the Sheraton Framingham Hotel & Conference Center.

Keep an eye out for registration, a call for volunteers for the planning team, and of course efforts to engage the broader NCDD community around conference content and theming. The call for workshop proposals will be distributed in a couple of months, but it’s never too soon to start thinking about what you’d like to present about and who you’d like to present with.

Keep an eye out for registration, a call for volunteers for the planning team, and of course efforts to engage the broader NCDD community around conference content and theming. The call for workshop proposals will be distributed in a couple of months, but it’s never too soon to start thinking about what you’d like to present about and who you’d like to present with.

Please share this post widely in your networks! Building on a 14-year legacy of popular, well-loved events, NCDD 2016 will be our 7th National Conference and just the latest of many events, programs and gatherings that NCDD has hosted since we formed in 2002.

Two Decades of Learning with Communities (Connections 2015)

The four-page article, Two Decades of Learning with Communities, by Phillip D. Lurie was published Fall 2015 in Kettering Foundation‘s annual newsletter, “Connections 2015 – Our History: Journeys in KF Research”. This article is about the Community Politics Workshops, which were developed train participants to understand delilberation and democratic public politics, then bring the knowledge back home to their communities. This process over these last two decades has revealed a lot about how communities work together democratically to address their problems. Connections 2015 is available for free PDF download on Kettering’s site here and read an excerpt from the article below.

When Communities Work Together

After more than a decade working with community-based teams, it is difficult to capture what we have learned in a few scant paragraphs. Moreover, these efforts have been one part of a larger research initiative, situated within KF’s Community Politics and Leadership program area, so the outcomes reflect the aggregation of data from all of these related efforts. Nonetheless, over the years, we’ve learned quite a bit about how communities work together democratically to address the problems they face.

• Community teams grew in their understanding of the goals and potential of deliberative practices.

As people began to engage in the practices of community politics, they tended to express their goals as either striving toward changing the political culture or making progress on a serious problem. This could be simplistically summarized as those who wanted to convene forums and change decision-making processes versus those who wanted action. However, over time, the thinking of most participants evolved to understand that both goals are intertwined. None believed deliberation was an end in itself, but they took differing views of the role of the convening organization in fostering action. Overall, we have learned that motivated citizen groups can understand the potential of public politics in their community.

• Deliberative practices, as conveyed to these community groups, were labor and time intensive.

One readily apparent problem faced by most teams, especially those that rely heavily on people who volunteer outside of their jobs, is that deliberative practices, at least as shared in the workshops, have been labor and time intensive. In many cases, team members report decreasing their activity because of other demands on their time. Finding ways to allow the public to do its work in ways that are less burdensome and more natural would allow teams, especially those without paid staff, to sustain the democratic practices over time.

• Community teams could frame issues and hold forums but had difficulty making an impact.

Overall, the community teams participating in these workshops could, with varying degrees of success, name, frame, convene deliberative dialogues, network, evaluate their efforts and progress, and, if desired, play a role in fostering citizen action. As a result, most community teams could claim some positive impacts as a result of their work. However, despite years of thoughtful effort, the Community Politics teams acknowledge that, at best, their work resulted in small pockets of change. At worst, some reflect that their efforts (despite being well thought out and labor intensive) had virtually no lasting impact on politics-as-usual or the community as a whole. Confronted with the limitations of largely volunteer teams and the realities of politics-as-usual in their communities, all of the community teams have struggled. Progress, if any, toward embedding and sustaining deliberative practices in the community in any way that really makes a difference or making a dent in serious problems has been uneven at best.

• Community teams often operated in a “parallel universe,” disconnected from politics-as-usual, or faced resistance when confronting politics-as-usual.

Community Politics teams had difficulty developing democratic practices that complement institutional practices. Oftentimes, community institutions used deliberative forums as a means to get input from citizens to justify existing proposals or satisfy a public participation requirement. Sometimes teams faced outright resistance from local institutions, which were hesitant to change. Team members often found that they were not able to bring enough local decision makers or funders to appreciate the need for deliberative public decision making, despite the best efforts of their team and their partner organizations. While the workshop series ended to allow for an internal review of our learning, the research has continued on in other ways. We are still experimenting today with how people in communities solve problems together. The foundation researches the ways that distinct groups attempt to constructively affect the politics of naming and framing problems in their community—as well as how they collectively address them. That is, how do innovations, which are designed to change the nature of the workings of political interactions in a community, work?

Learning exchanges are built around experiments and the practical implications of carrying out innovations. We are interested in learning more about:

1. how innovations can be initiated;

2. the potential barriers to trying new ways of solving problems together in communities;

3. assuming that innovations occur, the political outcomes of the innovations in practice, which includes changes in interactions regarding particular problems; and

4. the development of self-consciousness among citizens of key democratic practices and ways to make them citizen-driven.

We are studying how political entrepreneurship can be done with democratic intent.

About Kettering Foundation and Connections

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

Each issue of this annual newsletter focuses on a particular area of Kettering’s research. The 2015 issue, edited by Kettering program officer Melinda Gilmore and director of communications David Holwerk, focuses on our yearlong review of Kettering’s research over time.

Follow on Twitter: @KetteringFdn

Resource Link: www.kettering.org/sites/default/files/periodical-article/Lurie_2015.pdf

Hard Work and/or Intelligence

In early 2015, a team of researchers released intriguing findings from their study on gender distributions across academic disciplines.

They were curious why there is so much variation in gender representation across academia – disparity which is far from restricted to the STEM disciplines.

Women make up “approximately half of all Ph.D.’s in molecular biology and neuroscience in the United States, but fewer than 20% of all Ph.D.’s in physics and computer science.” Furthermore, women earn more than 70% of all Ph.D.’s in art history and psychology, but fewer than 35% of all Ph.D.’s in economics and philosophy.

So the problem is not simply one of raw representation.

Trying to get at the root causes of these variations, the team surveyed faculty, postdoctoral fellows, and graduate students from 30 disciplines across the United States – asking what qualities it takes to succeed in the respondents field.

Ultimately, they found that “women are underrepresented in fields whose practitioners believe that raw, innate talent is the main requirement for success.”

There is, of course, no reason to believe that women have, on average, less raw talent then men – but rather that women fail to advance in fields where raw talent – rather than hard work – is seen as a key factor for success.

It’s beyond the scope of this study to explain why the “extent to which practitioners of a discipline believe that success depends on sheer brilliance is a strong predictor” of gender representation. Though they do offer a few potential explanations:

The practitioners of disciplines that emphasize raw aptitude may doubt that women possess this sort of aptitude and may therefore exhibit biases against them. The emphasis on raw aptitude may activate the negative stereotypes in women’s own minds, making them vulnerable to stereotype threat. If women internalize the stereotypes, they may also decide that these fields are not for them. As a result of these processes, women may be less represented in “brilliance-required” fields.

In some ways, these explanations evoke the so-called “confidence gap” – the idea that women are more likely to attribute their success to good fortune or especially hard work; not to real achievement.

As the authors of The Confidence Code write, “Compared with men, women don’t consider themselves as ready for promotions, they predict they’ll do worse on tests, and they generally underestimate their abilities.”

Perhaps women shy away from these “brilliance-required” disciplines because – regardless of their actual talent – they simply don’t have the confidence required to pursue them.

….Or maybe they get pushed out by overbearing, patriarchal peers.

It’s hard to say. But I’ve been thinking about this 2014 study recently because I’ve found – as a first year Ph.D. student – that I am now constantly attributing my classroom success to hard work.

I’d hardly say that I’m brilliant, but I can work hard and figure stuff out along the way. I’d generally be inclined to attribute that sentiment to my working class background, but it’s interesting to think there may be a gender component there as well.

This all comes, of course, with an important word of caution: Too often, the solution to the confidence gap is seen as somehow “fixing” women – getting them to have the same high levels of confidence as the most self-aggrandizing of their male peers.

This is hardly a solution.

So let me be clear: it is not women who are broken, it’s the academy.

UBC Political Science leads a team to create new field of study (via UBC Faculty of Arts)