Monthly Archives: March 2015

generational change and the state of the press

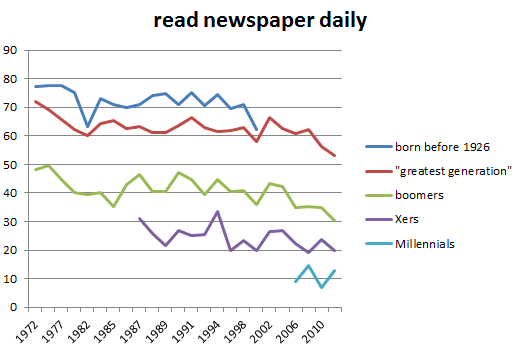

Reading a daily newspaper is a classic example of a generational habit. Since 2002, members of the “Greatest Generation,” Baby Boomers, and Gen-Xers have all reduced their reading of daily newspapers a bit. But the real reason for declining readership is generational replacement. Going back to the 1970s, we see a strong pattern that each generation reads the newspaper much less than its predecessors. That means that as succeeding generations compose larger shares of the population, total readership falls.

(Unfortunately, the GSS doesn’t provide a lengthy time series on Internet news, which would make an interesting comparison.)

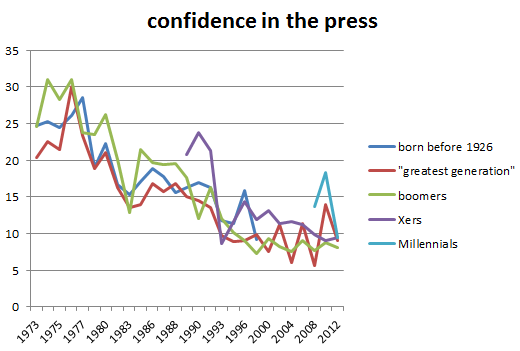

On the other hand, people’s confidence in the press is not a generational story at all. Everyone lost confidence, with the biggest decline occurring between 1977 and 1993. The generations that were old enough to be surveyed during those years sang in unison. Millennials were at first slightly more confident than other generations, but now they have the same views as all the older people.

Basically, this is a story of an industry losing the public’s trust (fairly or not)–it is not about the Millennials or any other generation.

The post generational change and the state of the press appeared first on Peter Levine.

Defending Free Software Against Privatizers

How can you protect a commons of software code from free riders who attempt to take it private for their commercial gain?

The traditional answer has been copyright-based licenses such as the General Public License, a legendary legal hack on copyright law that ensures the perpetual “shareability” of all licensed code. The GPL requires that third parties make any derivative software programs freely available to everyone and that they use the same license, thus ensuring that all future downstream uses of the code will also remain shareable.

But what happens if a company simply ignores the GPL and continues to free ride? We are about to find out.

After a long period of alleged non-compliance with the GPL, the software firm VMware is being sued by the Software Freedom Conservancy, a nonprofit home and infrastructure for free, libre and open source software projects. Most companies respect the GPL and other open source licenses, which is why this lawsuit is a rare enforcement action.

The Software Freedom Conservancy reports that it attempted to reason with VMWare, a $36 billion company traded on the New York Stock Exchange, before finally realizing that the company had no intention of complying. The last straw came when VMWare demanded that that lawyers sign a nondisclosure agreement just to discuss settlement terms.

The March Is Not Over Yet: A Different Education for the 21st Century

Bridging the Divides: Practical Dialogue and Creative Deliberation

We are happy to share the announcement below from NCDD Member Rosa Zubizarreta of DiaPraxis, which is an NCDD organizational member. Rosa’s announcement came via our great Submit-to-Blog Form. Do you have news you want to share with the NCDD network? Just click here to submit your news post for the NCDD Blog!

I am writing to let you know about two upcoming workshops in Dynamic Inquiry / Dynamic Facilitation. The first one is in Maine on March 27 – 29, sponsored by the Maine Association of Mediators. The second one is in NYC on April 17-19, sponsored by Focusing International.

We have a sliding-scale fee that ranges from $600 community rate to $1,200 corporate rate. In addition, NCDD members are eligible for a special discount rate we are offering during the next week: e-mail me at rosa[at]diapraxis[dot]com for more info.

So many good workshops out there! Each one valuable (at least all the ones I’ve taken!) and each one offering something unique.

Here’s what’s distinctive about ours: we offer an emergence-based, non-linear practice for transforming the energy of conflict into creativity, through cognitive empathy, welcoming initial solutions, and offering audacious invitations (so if you did appoint a committee to study the issue for a year, and they came up with a recommendation you loved, what might it be?) I’ve written a great deal about how this open-source process works, both in my book (www.fromconflict2creativity.com) as well as in various articles freely available on my website at www.diapraxis.com/resources.

What this means for practitioners: past workshop participants report feeling much more at ease in situations of conflict, developing practical skills for helping others shift from defensiveness to engagement, gaining more trust “in their bones” in emergent group process, and developing a greater ability to help groups shift into a state of creative flow. Due to the highly experiential nature of the workshop, many participants also report having personally transformative experiences during our time together.

Okay! If you’re interested, and would like to have a conversation, e-mail me to let me know.

Mechanics of Civic Games

After another great weekend of gaming, this time at PAX East, I, of course, have been thinking about what would go into a good civic game.

And just what is a civic game? Others might have different definitions, but I’d be inclined define that broadly as any game that increases a player’s civic skills, knowledge, or values.

And just how does any game increase someone’s skills, knowledge, or values around any topic?

Well, I suppose there are two broad elements which sets a game’s tone and thereby has the potential to impact a player: content and mechanics.

Content is what the game is actually about: are you in space? In the desert? Trying to survive the zombie apocalypse?

Mechanics is how the game actually works: Does the game rely on luck or strategy? Do you play with dice, cards, or other items? How do you interact with other players?

There is as much variety in styles of game mechanics as there is in types of game content.

It seems to me that a common failing of many education games is that they focus on content rather than mechanics – I have this information I want you to learn, and I “gamify” it with some set of game mechanics in the hopes of making learning more fun.

That’s actually kind of a backwards approach. The content of the game is interesting as a one-sentence overview: you are Little Red Riding Hood fighting zombie werewolves with a 9mm – but the mechanics of the game are what you really want to know:

How do I play?

And the mechanics of the game are absolutely critical in setting the tone and feeling of a game. The mechanics are what truly give a game its unique personality.

It’s not uncommon to hear people say, “I love that game, it’s got this really interesting mechanic…”

The mechanics are not an add-on that bring the content to life, the mechanics are the heart of the game itself.

And good mechanics, I think, are where civic games could really excel.

There is, of course, a whole genre of cooperative games – where players work together and either collectively win or collectively loose. There are semi-cooperative games, where players work in teams or form temporary alliances. These games may be inherently civic – forcing players to interact, work together, or perhaps to find mutual ground.

But, I suspect there are many more mechanics which could impart a civic lesson.

Take, for example, Penny Press. The content is simple: each player is a newspaper assigning reporters to stories and periodically going to press.

But the mechanics are great: there are different types of stories, and the public has different interest levels in those stories. If the public’s not interested in political stories, then the wise player won’t cover political stories – they’re not worth as many points.

Furthermore, public interest in a type of story is boosted by how many reporters are covering that type of story. If everybody’s writing about crime, public interest in crime will increase.

Finally, there are the mechanics of going to press itself. Stories are physically different sizes and you have to successfully lay them out within your newspaper. And you lose points if there are holes.

As a player, you find yourself thinking, “well, I don’t really want to cover sports, but…I need that story to make my layout work.” Even in this digital age, it’s not a bad approximation for the real impact of needing to manage resources.

“Newspapers” may be civic content itself, but it’s the game mechanics which really make it work.

Hannah Arendt and philosophy as a way of life

In “Martin Heidegger at Eighty” (1971), Arendt recalled:

The rumor about Heidegger put it quite simply: Thinking has come to life again. … People followed the rumor about Heidegger in order to learn thinking. What was experienced was that thinking as pure activity–and this means impelled neither by the thirst for knowledge, nor the drive for cognition–can become a passion which not so much rules and oppresses all other capacities and gifts, as it orders them and prevails through them. We are so accustomed to the old opposition of reason versus passion, spirit versus life, that the idea of passionate thinking, in which thinking and aliveness become one, takes us somewhat aback.

I first read this passage many years ago. Lacking any enthusiasm for Heidegger, I thought that Arendt was just celebrating her former teacher’s excellence and originality. “Thinking has come to life again” meant that someone as important as Kant or Hegel was again developing a philosophy, and one could study with him.

Now, having read works like Pierre Hadot’s Philosophy as a Way of Life, I think I understand Arendt better. People called “philosophers” have made at least three kinds of contribution over the millennia; Arendt was seeking a union of the three and believed that Heidegger offered it. That’s what she meant by “Thinking has come to life again.”

First, philosophers have interpreted other people’s thought in valuable ways. In this mode, philosophy is form of cultural critique or intellectual history. Describing the rumors about Heidegger’s seminar, Arendt recalled: “the cultural treasures of the past are being made to speak, in the course of which it turns out that they propose things altogether different from the familiar, worn-out trivialities they had been presumed to say. There exists a teacher; one can perhaps learn to think. …”

Second, philosophers have offered arguments: chains of reason that carry from a premise to a conclusion. If you hold the premise and the reasons are valid, you should endorse the conclusion. Following the argument to its end should change your store of beliefs, because now the conclusion should join the list of things you consider true.

Third, philosophers have taught reflective practices, methods of introspection or even meditation. These are different from interpretations of texts, because the process is more personal and creative. If a text is used it all, it is a prompt for introspection. These reflective techniques are also different from arguments, because they can begin with a range of premises and go in unexpected directions. They tend to require practice and repetition to yield their outcomes, which are changes in mental habits, not just lists of beliefs. You can read an argument once and evaluate it. You must introspect many times to have any impact on your psychology.

It makes sense to put these three contributions together because we are reasonable creatures (capable of offering and sharing reasons for what we do), but we are also habitual creatures (requiring mental discipline and practice to change our thinking) and historical creatures (shaped by the heritage of past thought). Reason without acquired habits of self-discipline is empty. But self-discipline without good reasons is blind and can even lead in evil directions. Both are rootless without a critical understanding of the ideas that have come before us.

Hadot argued that the schools of Greek philosophy between Aristotle and Christianity offered reflective practices more than arguments or readings. We misread a work like Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations if we assume that it is a set of conclusions backed by reasons. Instead, we will find there a record of a Stoic’s mental exercises, beginning with his daily thanks to each of his moral teachers. He lists his teachers and other exemplary men by name because he would actually visualize each of these people in turn. The Meditations shows us how.

Martha Nussbaum (in The Therapy of Desire, p. 353) and others have argued that Hadot exaggerated. The ancient Greek philosophical schools all took argumentation very seriously. (I would add that they were serious about interpreting older works, such as those of Plato and Aristotle.) But Hadot’s thesis strikes me as interesting even if he overstated it. The Greek schools combined argumentation with repeatable mental exercises and saw the two as closely linked. In this respect, they resembled the early Buddhist teachers who flourished at the same time. Today, the latter are often stereotyped as merely offering mental exercises (such as yoga), but they excelled at exacting formal argumentation. Indeed, the Buddhists and Hellenistic philosophers were in close contact in Northern India and learned from each other. (I see a distinction between Eastern and Western philosophy as useless, because each tradition encompasses enormous diversity, and the two have been closely linked.)

Hadot claimed, however, that Christianity ruptured the combination of argument and mental exercise that had been common in the Mediterranean and in Northern India before the Christian Era. Christians adopted all the major ideas of the classical Stoics but parceled them out. Abstract reasoning went to the medieval university, where Arendt’s “thirst for knowledge” and “drive for cognition” were prized. Hadot wrote, “In modern university philosophy, philosophy is obviously no longer a way of life or form of life unless it be the form of life of a professor of philosophy.” Meanwhile, the reflective practices went to monasteries.

Arendt perceived Heidegger as putting these parts back together. Reading classical works in his seminar (or in a reading group, called a Graecae) was a creative and spiritual exercise as well as an academic pursuit. Karl Jaspers held different substantive positions, but he had a similar view of philosophy, the discipline to which he had moved after a brilliant career in psychiatry. Elisabeth Young-Bruehl writes that Jaspers’

new orientation was summarized in many different ways, but this sentence is exemplary: ‘Philosophizing is real as it pervades an individual life at a given moment.’ For Hannah Arendt, this concrete approach was a revelation; and Jaspers living his philosophy was an example to her: ‘I perceived his Reason in praxis, so to speak,’ she remembered (Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World, pp. 63-4).

Arendt fairly quickly decided that “introspection” was a self-indulgent dead-end and that Heidegger’s philosophy was selfishly egoistic. Then the Nazi takeover of 1933 pressed her into something new, as she assisted enemies of the regime to escape and then escaped herself. She found deep satisfaction in what she called “action.” From then on, she sought to combine “thinking” (disciplined inquiry) with political action in ways that were meant to pervade her whole life.

That combination is hard to find today, if it can be found at all. Moral philosophy is dominated by an argumentative mode that doesn’t take seriously mental exercises and practices. Meditation is increasingly common but usually separate from formal argumentation and moral justification. Meanwhile, “therapy”–the ancient Greeks’ word for what philosophers offered–has been taken over by clinical psychology. That discipline does good in the world but misses the ancient objectives of philosophy. Modern therapy defines the goals in terms of health, normality, or happiness (as reported by the patient). Therapy is successful if the patient lacks any identifiable pathologies, such as depression or anxiety; behaves and thinks in ways that are statistically typical for people of her age and situation; and feels OK. Gone is a restless quest for truth and rightness that can upset one’s equilibrium, make one behave unusually, and even bring about mental anguish. To recover that tradition, we would need thinking to come alive again.

The post Hannah Arendt and philosophy as a way of life appeared first on Peter Levine.

February 2015 Confab Call on Newcomers, Latecomers, and Disrupters

On February 19th, NCDD hosted a Confab Call on “Newcomers, Latecomers, and Disrupters: Strategies for Sustainable and Productive Engagement” featuring NCDD members Sarah Read and Christoph Berendes.

Sarah and Chris described the structures they’ve used for these kinds of challenges, process elements that affect success, and demonstrated web tools that can help. Seventy people registered for this call! If you missed the confab and are interested in learning more, you can now watch the presentation and more at the links below.

Sarah and Chris described the structures they’ve used for these kinds of challenges, process elements that affect success, and demonstrated web tools that can help. Seventy people registered for this call! If you missed the confab and are interested in learning more, you can now watch the presentation and more at the links below.

- Watch the presentation from the February 19, 2015 Confab Call.

- Read over Sarah and Chris’ notes

- Check out past Confab Calls & Tech Tuesdays!

You can also learn more about NCDD’s Confab Calls and other events in our Event Section.

How Much Will It Cost?

is our constitutional order doomed?

Mathew Yglesias has brought renewed attention to Juan Linz’ thesis that our constitutional order is doomed. The basic idea is that if the chief executive and the legislature are elected separately, they can belong to different parties. In such cases, the legislature has every incentive to undermine the president, who will respond by expanding executive power. That situation will degenerate until the constitution fails, as it has in almost every presidential system outside the USA. See Yglesias’ Vox piece, “American Democracy is Doomed,” Jonathan Chait’s response (“There’s a Chance American Democracy Is Not Doomed“), and my own post “Are we seeing the fatal flaw of a presidential constitution?”

The Linz thesis requires an explanation for why the US system has not already collapsed after more than two centuries. The leading explanation is that we have never actually had two parties in Congress, notwithstanding the labels. Internal party splits have caused us to have at least three–and often four or more–effective parties. Thus presidents have been able to construct governing coalitions even when they face a majority of the opposite party. Reagan, for example, got most of his agenda through Tip O’Neil’s Democratic House because Southern Democrats voted with Republicans on key issues.

Our current situation looks unprecedented because the two parties are now perfectly polarized, with all the Democrats to the left of all the Republicans. Thus the Linz thesis explains paralysis and executive unilateralism under Obama and predicts worse to come.

But then we observe the Department of Homeland Security funding bill pass the Republican House with unanimous Democratic support. Democrats are also saying they would protect Speaker Boehner from a Tea Party effort to unseat him. (The Speaker is chosen by majority rule, so Boehner could hold his gavel with a mix of Republican and Democratic votes). These two examples suggest that Boehner is in the same place as O’Neil during the Reagan Administration. He leads a caucus that formally and rhetorically opposes the president. But sometimes the governing coalition in the House consists of 75 Republicans plus all the Democrats. Boehner is like a Prime Minister whose own party (the Center-Right) is smaller than its coalition partner (the Center-Left) but who alone can command more than 50% in votes of no confidence.

This situation only applies some of the time. Boehner does not like (and will not even acknowledge) his dependence on Democrats. It poses a serious problem for all Republicans, not just for Tea Partiers, because it cedes considerable power to the other party. Thus Republicans will make creative and sustained efforts to change the situation. But to the extent that it prevails, we will return to the classic US pattern instead of dissolving into a Linzian nightmare.

The post is our constitutional order doomed? appeared first on Peter Levine.