Charlie Hebdo, American academia, and free speech

David Brooks begins today’s column: “The journalists at Charlie Hebdo are now rightly being celebrated as martyrs on behalf of freedom of expression, but let’s face it: If they had tried to publish their satirical newspaper on any American university campus over the last two decades it wouldn’t have lasted 30 seconds. Student and faculty groups would have accused them of hate speech. The administration would have cut financing and shut them down.”

It’s critical to distinguish between two questions: 1) How should I (or a small group) manage a forum of communication that is under my or our control? and 2) What rights do people have to run their own fora?

A forum might be a newspaper or a magazine, a course, a speaker series, a website, or the wall outside my office. If I (either alone or with colleagues) am responsible for that forum, then I must decide how it should be run. It can be an open forum in which anyone may post anything. But that is a choice, not an obligation, and often it’s a bad one. I much prefer the edited and curated homepage of the New York Times to an unmoderated chat. Assuming we choose to manage a space, we must make constant decisions about what and whom to include and exclude. It is appropriate to consider questions of relevance, quality, impact on various people, diversity, consistency, fairness, and more.

A society, however, should not be a forum with one set of rules and values. It should include an enormous array of quasi-autonomous fora under many different managers, rules, and value-systems. Individuals and voluntary groups should have very extensive rights to create and run their own fora in their own ways.

Thus there is no contradiction at all between saying (a) I would rather not post an anti-Islamic cartoon on my website or invite an anti-Islamic speaker to address my class, and (b) the cold-blooded murder of Charlie Hebdo’s staff was a fascistic assault on human rights and liberty. These are actually closely related ideas, because both stem from the fundamental principle that forums of communication must be plural and autonomous.

Thus I am not concerned or embarrassed that American academic institutions may be reluctant to invite inflammatory anti-Muslim speakers. That’s a reasonable judgment by the organizers of those particular fora.

One thing that does worry me is the gradual evolution of each American university from a plural array of fora into a singular forum. In some ideal world, a university would be a space in which tenured faculty and students can exercise a high degree of free speech, creating their own mini-fora: diverse classes, speaker series, associations, and publications. To be sure, certain aspects of the university–such as the annual commencement address–must be chosen by the institution and thus must be governed by uniform criteria and processes. But in a healthy university, those centralized fora do not crowd out all the diversity.

I see increased centralization of control over a university’s discourse and inquiry, due to: the influence of external donors, the severe shortage of tenured positions, the rising share of contingent faculty, IRB review, multiplying layers of administration (so writes an associate dean for research), increasingly sophisticated PR efforts, and the growing role of metrics and assessments. Campus speech codes and other explicit regulations of speech may also play a role–and I am skeptical of these interventions–but I don’t think they represent the main threat to pluralism.

The post Charlie Hebdo, American academia, and free speech appeared first on Peter Levine.

Guerilla Service

Sometimes it takes an awful long time to get things done.

That’s not necessarily anybody’s fault, but it is a reality of bureaucracy – a process which does, indeed, have many benefits in it’s favor.

But when you’re outside the the bureaucracy, when it’s not your money to spend or your ducks to get in a row, delay can seem long and unnecessary.

Years ago – not too long before they rebuilt a certain MBTA stop – I used to go through that stop every day.

The paint was peeling in a most unsightly manner. This left the bare wood exposed to the elements, which only compounded the dilemma. It had been getting progressively worse over the years and it was getting to the point where a homeowner’s neighbors might start complaining.

Something really needed to be done.

Of course, something was done – the whole station was replaced a few years later. But as I stared at the peeling paint, I couldn’t help but wonder if something should happen sooner.

I had this dream – a crazy idea, of course, and I never did end up acting on it. But I couldn’t help but wonder what would happen –

If a broken into the station at night an repainted the walls.

I really wanted to do it.

Of course, the whole idea was impractical. I’d need to strip the wood, treat the wood, paint the wood, and probably let it dry between a few coats. That would never happen in one night. Even if I got a few people together.

It was a shame it wouldn’t have worked.

I always wondered what would happen if somebody did that. Technically it would be trespassing and vandalism, but would the state press charges if the work was completed in a professional manner? Would their be complaints about a citizen service vigilante taking on this work which needed to be done?

I didn’t know, and I really wanted to hear the conversation after.

Of course, there is another point, which could be raised in the face of well-meaning service: does a citizen’s volunteer work imply that such tasks are not the responsibility of the government?

A city, for example, ought to devote resources to maintaining it’s public parks, so a dedicated citizen ought to demand government action rather than cleaning the park themselves.

That is a valid concern, but I’m not sure what is better. All I know is that when I see old, dingy paint peeling off of old, dingy, walls –

I just want to get it done.

the core of liberalism

Real ideological movements are under no one’s control. They shape-shift and amalgamate until it is both difficult and misleading to define them in terms of core principles. The debate about their meaning not only reflects authentic intellectual inquiry but also a series of power-plays. If you can make conservatism mean what you want it to mean, for example, then you can line up support from people who identify as conservatives.

Michael Freeden studies the patterns of ideas that form political ideologies, which he calls their “morphologies.” He notes, “Morphology is not always consciously designed. Even when design enters the picture, it is partial, fragmented, and undergirded by layers of cultural meaning that are pre-assimilated into rational thinking.”*

Still, we can learn from ideologies, and not only from the relatively transparent and organized arguments that their theorists set down on paper. Political movements reflect accumulated experience. Although some movements are beyond the pale, all reasonably mainstream political ideologies invoke clusters of central ideas that deserve consideration.

In an earlier post, I argued that the valuable, core, animating impulse of conservatism is resistance to human arrogance. Conservatism can take different forms depending on the form of arrogance that is assumed to be most dangerous. If it’s the arrogance of central state planners, laissez-faire looks attractive. If it’s the arrogance of godless human beings, religious authority may look better. If it’s the arrogance of faceless corporations, small human communities may seem safer. Although these are disparate enemies, they are all charged with the same fundamental sin: blindness to human cognitive and ethical limitations.

What, then of liberalism? Empirically, it is at least as various as conservatism is. It would be appropriate to apply the word “liberal” to a New Deal social democrat or to a minimal-government libertarian, although they represent opposite poles in the US political debate.

Nevertheless, as with conservatism, we can undertake an appreciative reconstruction of liberalism as an ethical orientation. Its valuable, core, animating impulse is a high regard for the individual’s inner life–her ideas, passions, and commitments–and their expression in her personal behavior. That attitude can recommend a range of institutions, from a hyper-minimal state (to protect the individual against tyranny) to a strong social welfare state (to enable her to develop her individuality). That is why liberals span the US political spectrum. Yet not everyone is a liberal. If you see a community or a nation as having intrinsic value, you are (at least in that respect) distant from liberalism. If you see equality as an end, rather than as a potential means to individuals’ development, you diverge from liberalism. If you are confident that one or a few ways of life embody the human good and should be encouraged or required, you are not fully liberal.

Although liberalism permits a wide range of political institutions, it has a fairly consistent cultural agenda. It favors the cultivation and appreciation of complex and diverse personalities. It is tolerant of the contemplative (rather than the active) life, of irony and ambiguity, of personal expressions against the crowd. Its most characteristic cultural form is the sensitive depiction of individuals in intimate relationships without the overlay of a strong authorial voice–as in the nineteenth-century novel or the Impressionist portrait. “Negative capability” (the ability not to take a position when describing the world) is the aesthetic analog of the liberal’s political principle of tolerance.

The poet Mark Strand gave a characteristic liberal’s response to the question, “What is your view of the function of poetry in today’s society?”:

Poetry delivers an inner life that is articulated to the reader. People have inner lives, but they are poorly expressed and rarely known. They have no language by which to bring it out into the open. … Poetry helps us imagine what it’s like to be human. I wish more politicians and heads of state would begin to imagine what it’s like to be human. They’ve forgotten, and it leads to bad things. If you can’t empathize, it’s hard to be decent; it’s hard to know what the other guy’s feeling. They talk from such a distance that they don’t see differences; they don’t see the little things that make up a life. They see numbers; they see generalities. They deal in sound bytes and vacuous speeches; when you read them again, they don’t mean anything.

These may be clichés (and Strand’s generalizations about politicians are just as empty as their alleged generalization about citizens). But in a poem like “The Way it Is,” Strand shows what he means. The narrator is beset by his jingoistic, gun-toting neighbor (“wearing the sleek / mask of a hawk with a large beak”) and by horsemen “riding around [the people], telling them why / they should die.” In other words, he fears the individual with no inner life and the faceless state. “I crouch / under the kitchen table, telling myself / I am a dog, who would kill a dog?” This is the liberal’s nightmare, but the poem is an act of freedom as self-expression.

Along similar lines, Lionel Trilling endorsed impersonal rules and institutions that enhanced freedom and happiness, yet he wished to “recall liberalism to its first essential imagination of variousness and possibility, which implies the awareness of complexity and difficulty.”** For Trilling, sensitive literary criticism was a characteristic liberal act because it involved the recovery of another individual’s thought.

On this definition, you can be a liberal and also a conservative, a socialist, and/or a majoritarian; those categories are not mutually exclusive. But liberalism points in certain directions and warns against certain dangers often forgotten in other ideologies.

—

*Michael Freeden, “The Morphological Analysis of Ideology,” in Freeden, Lyman Tower Sargent, and Marc Stears (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford, 2013), pp. 115-137 (quoting p. 122.)

**Trilling, The Liberal Imagination: Essays on Literature and Society (1950) (New York: New York Review of Books, 2008), p. xxi.

The post the core of liberalism appeared first on Peter Levine.

Love’s Such An Old Fashioned Word

It’s possible I have simply spent too much time in New England, but it seems, perhaps, there is only a certain amount of care one ought to express for others – that anything more would be unseemly.

This statement, of course, is at once complicated by the vast array of different types of relationships one has with others.

A simplified model considers these relationships as a series of concentric circles with descending levels of intimacy: you at the center, your closest family next, good friends, followed by acquaintances and circumscribed by a band of strangers. There may be other levels in there or the whole thing could be considered as a spectrum, but the basic idea is the same: there are a few people we are very close to, a whole mess of people we have no closeness to, and a lot of people at various levels in between.

There’s a lot of value in this model. It can be used, for example, to help develop healthy relationships with a mutually-agreed upon level of intimacy. If you’re wondering whether you should make an inappropriate joke to someone, for example, it’s probably wise to stick to those inner circles.

But this model is often assumed to double as a guide for compassion – with a person showing more concern for their inner circles and decreasing concern moving outward.

And in some ways that approach makes sense. After all, it seems antithetical to human nature – and arguably somewhat abhorrent – to love a stranger as much as you love your child.

But concentric circles of concern quickly break down as moral guide: Should you be more moved by the tragedy of “someone like you” than by the tragedy of someone completely foreign? Feeling that way is arguably natural, but it’s repugnant to think that a white person should indeed care more for a European than an African.

And while this, of course, raises important and critical points regarding international aid and human dignity, I find myself particularly interested in another level of this mystery.

Perhaps it’s a less pressing moral question, but I find it more relevant to every day life – what amount of care, I wonder, ought a person to show to all the random people who come in and out of their life?

I imagine there’s a certain baseline of compassion or concern most people would agree they ought to express – perhaps most simply that they shouldn’t do violence to others.

But that’s different from having and showing real care and compassion for those you meet. At some level, this sounds like an obvious thing every good person ought to do, but in practice…it’s not that easy and mostly it feels awkward.

I’ve written before about debating whether an action is “crazy or thoughtful” – too often doing something “nice” feels dangerously close to doing something “crazy.” As if one ought not too care too much about anyone beyond their most inner circle.

And while I’ve been using words like care, concern, and compassion – I’m not sure those words are quite what I mean. Love is, perhaps, too strong in English, but it may be somewhat closer. I imagine the Greeks had the perfect word for it – a sort of permeating love for humanity.

However it is, I sometimes think Queen put it best –

‘Cause love’s such an old-fashioned word

And love dares you to care for

The people on the edge of the night

And love dares you to change our way of

Caring about ourselves

This is our last dance

This is our last dance

This is ourselves

….Under pressure.

three ways of thinking about social reform

A group has been discussing how to improve upward economic mobility in the Boston metro area, which is booming but leaving a lot of people behind. I do not know much about economic mobility, nor do I lead an antipoverty organization, so I have found it a privilege to be in the room with people who have real knowledge and clout.

In the discussions so far, I detect three theses. When I mentioned this list, some people felt that they are all true. Indeed, the ideas may fit together in various combinations, but I see tensions among them.

1. We know how to improve the prospects of low-income people; we just don’t have the will to do it. Innovation should be at the political level, changing the balance of power or the messages that resonate.

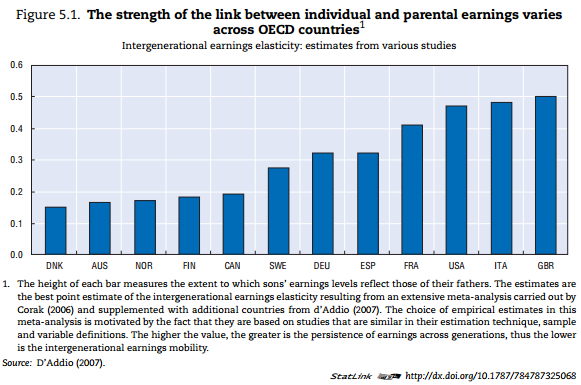

Probably the strongest evidence for that thesis is international. This OECD publication is one of many that shows poor intergenerational mobility in the US compared to countries like Denmark, Australia, and Norway. The same study finds that public investment in early childhood correlates with better mobility. We don’t invest much in preschool in the US. The reason is arguably that affluent suburbanites don’t vote for it because they don’t need it, while poor people don’t vote for it because they are generally disenfranchised and dispirited. So we need political strategies to change voters’ preferences to shift government.

2. We don’t know how to help people move up the mobility ladder in a post-industrial, knowledge-based, global economy. We need innovative programs and R&D.

Ron Haskins recently wrote, “Despite decades of efforts and trillions of dollars in spending, rigorous evaluations typically find that around 75 percent of programs or practices that are intended to help people do better at school or at work have little or no effect.” That’s a controversial claim; I have previously addressed the complex question of whether to rely on randomized studies. But it is a plausible claim, especially if we restrict it to hands-on service programs (in contrast to entitlement transfers). To be sure, we see more intergenerational mobility in Denmark than in the US, and Denmark has large-scale policies that probably work–but I’ll bet they work less well than they used to, and they may not apply in situations like our massively deindustrialized cities. So there is a case for finding new strategies that really work instead of spending tons of money on things that don’t.

3. People in poor communities should determine their own futures.

Both #1 and #2 can be read as “We should do various things for–or to–people in poor communities.” Clearly, they need resources. But perhaps “we” should show a little more modesty. People in poor communities should not only decide how to use resources but also do the (paid) work of community development, creating their own solutions.

Again, I think these theses can fit together in various ways; many individuals see merit in two or even three of them. But they do pull you in different directions.

The post three ways of thinking about social reform appeared first on Peter Levine.

NCDD Member Orgs Form New PB Research Board

In case you missed it, the Participatory Budgeting Project and Public Agenda – two key NCDD organizational members – announced last fall that they have formed the first North American research board to study the participatory budgeting process. Not only is this an important and exciting development for the field, but we are proud to count two NCDD members – Matt Leighninger and Paolo Spada – among the new board. Read the announcement below or find the original version here.

PBP and Public Agenda are facilitating the launch of the North American Participatory Budgeting Research Board with various participatory budgeting (PB) evaluators, academics, and researchers. Shortly after the 3rd International Conference on PB in North America, we came together in Oakland for our first meeting.

PBP and Public Agenda are facilitating the launch of the North American Participatory Budgeting Research Board with various participatory budgeting (PB) evaluators, academics, and researchers. Shortly after the 3rd International Conference on PB in North America, we came together in Oakland for our first meeting.

The goal of the board is to support the evaluation of PB processes across the US and Canada and guide a broader research agenda for PB. Over the years of PB in North America, many board members have already been informally collaborating and supporting one another’s work. With the rapid growth of PB in North America we see the importance of establishing the formal infrastructure to further strengthen and promote the research and evaluation.

The First Meeting and Historical Context

On a Sunday morning in Oakland in September, a group of leading researchers and evaluators converged at the PBP office for the first meeting of the North American PB Research Board. It was a rare and exciting moment: two hours of deep discussion amongst passionate individuals who have committed countless hours, and sometimes entire careers, to researching and evaluating PB processes in North America and overseas. This had the feeling of something that could make a vital contribution to the spread and improvement of PB in North America.

Research and evaluation have long been central features of North American PB processes. Academic researchers from diverse backgrounds have been fascinated with measuring the contribution of PB to social justice and the reform of democratic institutions. Local evaluation teams, particularly in NYC and Chicago, have conducted huge data collection efforts on an annual basis to ensure that fundamental questions such as “who participates?” and “what are the impacts of PB?” can be accurately answered.

Often the agendas of these researchers and evaluators have overlapped and presented opportunities for collaboration. PBP has played a key role in supporting both research and evaluation but, with the rapid expansion of PB in North America, we recognized the need for a more formal research and evaluation infrastructure in order to measure and communicate the impacts of PB across cities.

Partnering to Build Expertise and Capacity

Having identified this need, we saw the opportunity to partner with Public Agenda, a non-profit organization based in NYC with vast experience in research and public engagement. With leadership from Public Agenda, support from PBP, and contributions from leading researchers, the North American PB Research Board generates new capacity to expand and deepen PB.

Over 2014-2015 the board will have 17 members, including experienced PB evaluators and researchers based at universities and non-profit organizations.

2014-2015 North American PB Research Board

- Gianpaolo Baiocchi, New York University

- Thea Crum,Great Cities Institute, University of Illinois-Chicago

- Benjamin Goldfrank, Seton Hall University

- Ron Hayduk, Queens College, CUNY

- Gabe Hetland , University of California-Berkeley

- Alexa Kasdan, Community Development Project, Urban Justice Center

- Matt Leighninger, Deliberative Democracy Consortium

- Erin Markman, Community Development Project, Urban Justice Center

- Stephanie McNulty, Franklin and Marshall College

- Ana Paula Pimental Walker, University of Michigan

- Sonya Reynolds, New York Civic Engagement Table

- Daniel Schugurensky, Arizona State University

- Paolo Spada, Participedia

- Celina Su, Brooklyn College, CUNY

- Rachel Swaner, New York University

- Brian Wampler, Boise State University

- Rachel Weber, Great Cities Institute, University of Illinois-Chicago

- Erik Wright, University of Wisconsin-Madison

NCDD congratulates everyone involved in taking this important step forward for PB and for the field! To find the original announcement about the Research Board, visit www.participatorybudgeting.org/blog/new-research-board-to-evaluate-pb.

New Evidence that Citizen Engagement Increases Tax Revenues

pic by Tax Credits on flickr

Quite a while ago, drawing mainly from the literature on tax morale, I posted about the evidence on the relationship between citizen engagement and tax revenues, in which participatory processes lead to increased tax compliance (as a side note, I’m still surprised how those working with citizen engagement are unaware of this evidence).

Until very recently this evidence was based on observational studies, both qualitative and quantitative. Now we have – to my knowledge – the first experimental evidence that links citizen participation and tax compliance. A new working paper published by Diether Beuermann and Maria Amelina present the results of a randomized experiment in Russia, described in the abstract below:

This paper provides the first experimental evaluation of the participatory budgeting model showing that it increased public participation in the process of public decision making, increased local tax revenues collection, channeled larger fractions of public budgets to services stated as top priorities by citizens, and increased satisfaction levels with public services. These effects, however, were found only when the model was implemented in already-mature administratively and politically decentralized local governments. The findings highlight the importance of initial conditions with respect to the decentralization context for the success of participatory governance.

In my opinion, this paper is important for a number of reasons, some of which are worth highlighting here. First, it adds substantive support to the evidence on the positive relationship between citizen engagement and tax revenues. Second, in contrast to studies suggesting that participatory innovations are most likely to work when they are “organic”, or “bottom-up”, this paper shows how external actors can induce the implementation of successful participatory experiences. Third, I could not help but notice that two commonplace explanations for the success of citizen engagement initiatives, “strong civil society” and “political will”, do not feature in the study as prominent success factors. Last, but not least, the paper draws attention to how institutional settings matter (i.e. decentralization). Here, the jack-of-all-trades (yet not very useful) “context matters”, could easily be replaced by “institutions matter”.

You can read the full paper here [PDF].

Public Conversations Project Rolls Out New Website

We are pleased to share that our partners with the Public Conversations Project – one of our great NCDD organizational members that helped sponsor NCDD 2014 –  just announced the roll out of their brand new website this week.

just announced the roll out of their brand new website this week.

PCP’s new website is dynamic, user-friendly, and home to a good deal of content that NCDD members will find useful, including free dialogue resources, stories of dialogue across the world, and information on their approach. They sent out an email announcing the change today, and here’s what PCP had to say:

Public Conversations Project is excited to celebrate the new year with a new website, at www.publicconversations.org. Our 25 years in the field of dialogue have taught us the value of a fresh perspective, and we are proud to share our new look with friends and supporters.

Check out our free dialogue resources, meet our staff, explore stories of dialogue across the world, and get information about our practitioners and upcoming workshops.

We invite you to join the conversation and let us know what you think of our new look. Reach out to us via email at marketing@publicconversations.org or find us on social media.

We encourage you to check out the new and improved PCP website soon and to stay tuned to their social media for continued updates on the new features of their website. And congratulations to the PCP team on the accomplishment!

Why Read Dead Authors?

There are all sorts of clichéd arguments for why one ought to study the past or explore the wisdom of long dead scholars.

Yes, yes, those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

Or, perhaps, with so much wisdom in our collective past, we shouldn’t waste our time reinventing the wheel.

Sigh.

It’s not that those aren’t good arguments. They’re perfectly fine arguments, and perfectly fine reasons for studying ancient works.

But. There’s something more –

The way I perceive and understand the world is deeply rooted in my given place and time. The way I think is shaped not only by my individual experiences, but my broader cultural context.

That is to say, not only can an individual’s morals be considered as a network, but the ideas a person understands can be considered as a network. There are plenty of values which I don’t hold as my own, but when I meet someone with those values I understand where they are coming from.

In some ways, this understanding is simply a feature of my own network – when someone holds a value different from my own, I naturally try to understand it using the network of values I do hold.

But I’m not sure relying on our existing network provides a broad enough perspective.

Thales of Miletus is famously recorded as having thought that archê, the ultimate principle, was water.

Did you miss that?

Everything is water.

What does that mean?

I’ve read many (inconsistent) explanations of what that means, and I suppose I understand it enough to try to explain it. But, really…it’s kind of crazy talk. Right? I remember learning about Thales in high school and laughing to myself. Man, those ancient Greeks were crazy.

But his argument was also important.

Interpreting his belief quite literally, in the physics realm, Thales of Miletus is credited with being the first (in recorded, Western, history) to conceive of the idea of a fundamental particle. That is to say, with his argument that “everything is water,” Thales led humanity down a path of thought which brought us to molecules, atoms, protons, quarks, and leptons.

There’s a moral in there about how we should always listen to our crazy elders because you never know what nugget of wisdom will propel you forward –

But that’s not my point.

“Everything is water” sounds crazy because I have no context through which to interpret that phrase. Being more accurate that “archê is water” doesn’t help.

But it made sense at the time.

In Metaphysics, Artistole explains simply:

Thales, the founder of this type of philosophy, says the principle is water (for which reason he declared that the earth rests on water), getting the notion perhaps from seeing that the nutriment of all things is moist, and that heat itself is generated from the moist and kept alive by it (and that from which they come to be is a principle of all things). He got his notion from this fact, and from the fact that the seeds of all things have a moist nature, and that water is the origin of the nature of moist things.

And then he moves on, as if that’s all you might ever need to know about someone who thought that water was the essence of the universe.

Perhaps Thales is a trivial example – it may not be all that relevant exactly what Thales thought or meant. But I don’t think I’ve ever come across a more foreign idea than that.

And that’s the reason why I like to study dead authors from around the world.

Understandings of public and private, political and social, citizen and society have varied not only across the globe but across time.

It’s hard to see the assumptions of your culture when you are a part of it. But trying to understand someone else’s perspective – not only a moral system, but a whole framework and way of thinking that is foreign to you – expands your capacity to think, to examine, or perhaps simply…to consider the possibilities.

And that has real value.