The Presidential election and the week following has brought the deep divides in this nation to a head, and brought to light numerous issues in our country. The results show us that huge swaths of the country feel unheard and anxious about the future, and sadly, many responses to the election and events taking place in its wake have highlighted issues of pent up frustration, racism, bigotry, and more.

We don’t know for sure what the coming weeks, months, and years will bring, but we do know this: dialogue & deliberation is more critical than ever. Our community may need some time to process this and think about what to do next, but we know our involvement is essential to helping bridge our divides, addressing substantive disagreements, and finding ways for us to work and move forward together as a nation.

The Needs We See & Our Network’s Response

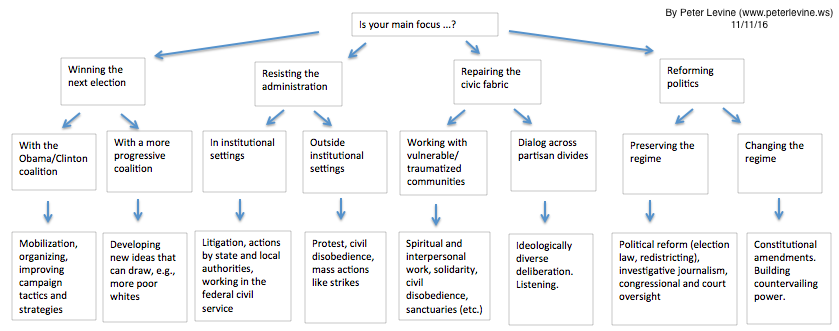

There are many different needs that our country and our communities have right now, but we see a few key needs that stand out as ones that are especially suited for D&D solutions: bridging long-standing divides, processing hopes and fears together, encouraging and maintaining civility in our conversations, and humanizing groups who have become “the other.”

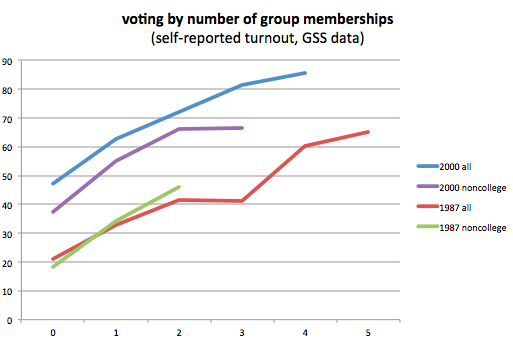

We at NCDD have been discussing bridging our divides all year, and we have an ongoing campaign focused on that work, but the election highlights that need even more. The partisan divide is always there, of course, as well as our historical racial divides. But the election also highlighted the disconnect between rural and urban communities, between people who attended college and who didn’t, and between people from different class statuses. The D&D community needs to be responding to all of these divides – exploring their origins, understanding how they impact people, and imagining how we can dissolve them. Essential Partners just released a Guide for Reaching Across Red-Blue Divides that can be a helpful tool for these needed conversations, and there are more.

After the election, people also need to process and reflect. There is a critical need for dialogue right now where people can express how they’re feeling and explore their hopes and worries for the weeks and months to come. Processes like Conversation Cafe are easy access points for people looking to have a dialogue to reflect on the election as well as what they’d like to see happen now. It’s a tool that provides the structure people need to have thoughtful, respectful conversations in person, and Essential Partners’ work to engage people about what happens #AfterNov8 is a good social media complement.

There is also a need – possibly more than ever – for civility in our discussions that allows us to disagree without attacking each other. D&D practitioners have our work cut out for us in helping people approach both public and private post-election conversations with civility and respect. Several NCDD members are leading efforts to maintain and restore it, with the National Institute for Civil Discourse leading the charge in their Revive Civility campaign, yet much more is needed.

Finally and maybe most importantly, the country needs help finding approaches to humanizing the people and groups that have become “the other” – unapproachable and unredeemable caricatures – to our own groups. Conservatives are feeling unfairly vilified and misunderstood. Many immigrants, Muslims, and women are feeling threatened, at risk, and unwelcome. NCDD is continuing to support this work and promote collaboration through our new Race, Police, & Reconciliation listserv, and Not In Our Town has many resources for opposing bullying and hate groups that we recommend checking out. But this strand of potentially transformational D&D work needs much more energy and investment devoted to it in coming months and years.

Finally and maybe most importantly, the country needs help finding approaches to humanizing the people and groups that have become “the other” – unapproachable and unredeemable caricatures – to our own groups. Conservatives are feeling unfairly vilified and misunderstood. Many immigrants, Muslims, and women are feeling threatened, at risk, and unwelcome. NCDD is continuing to support this work and promote collaboration through our new Race, Police, & Reconciliation listserv, and Not In Our Town has many resources for opposing bullying and hate groups that we recommend checking out. But this strand of potentially transformational D&D work needs much more energy and investment devoted to it in coming months and years.

Share What You’re Doing

As we look ahead, we want to ask NCDD members and our broader network, what work are you doing in response to the election and the issues that have arisen? What resources can you share to help others at this time?

Please share any efforts you are making, ideas you have, resources or tools you know of that could be helpful in the comments section of this post or on the #BridgingOurDivides campaign post. We learn so much from being in communication with one another about what we’re up to. NCDD will continue to share your responses on the NCDD Blog and our social media using the hashtag #BridgingOurDivides to continue lifting up stories and resources to a broader audience, and we’ll be working to compile the best divide-bridging resources in our Resource Center.

Furthermore, tell us what you think we can be doing together as a community to address the post-election landscape. Let’s talk with one another about how we can work collaboratively to engage the public and bring peaceful interactions and greater understanding to everyone.

It’s clear there is a lot of work to do to help our country come together, and heal the divides this election season has unearthed or widened. Our community is well suited to do this work, and we call on all of us to be supporting one another in our efforts.

Continue the conversation with NCDD on social media: Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn.