Two theses for today: 1) You have a right (and even an obligation) to be concerned about your own inner wellbeing–call it happiness, peace, lack of suffering, equanimity, satisfaction, or mental health. And 2) Inner wellbeing is a complex issue, not just a matter of maximizing a simple mental state, such as pleasure.

Why it is right to be concerned about your inner wellbeing

The first premise is far from obvious. More than three million children die every year from undernutrition alone. Their deaths are stark evidence of grave deprivation that affects many more who do not happen to die. Almost half a million human beings are murdered annually around the world, again just a fraction of those who suffer from intentional violence. And even within the United States, more than two million of our fellow citizens are incarcerated, reflecting both severe hardship for the prisoners as well as a trail of harms that many of them have done to others. Under circumstances like these, why may a person like me (who is healthy, safe, and affluent) pay any attention to improving my own inner wellbeing?

No doubt, I ought to be concerned about others. Yet anyone’s inner welfare is also a valid and important concern for that person. This is because it seems to be necessary for human beings to be involved in making themselves happy or satisfied; no one can simply do that for us. So even if the goal were to maximize everyone’s happiness, that couldn’t be accomplished by a world of individuals who were concerned only with other people. They would also have to be responsible for themselves. Pure altruism or other-regardingness is not the ideal, because there would then be no one in a position to make each individual happier.

To be sure, we can ruin other people’s wellbeing, for instance by putting them in fear or anguish. And we can fail to remedy objective circumstances, such as poverty or political oppression, that prevent others from achieving wellbeing. In other words, outer circumstances and inner wellbeing are related. But the links are fairly loose. Some people who know no physical pain and have plenty of money are nevertheless miserable to the point of suicide. Poor villagers who live under a repressive government can be happier than wealthy suburbanites who are well treated by the state. We could make the distribution of rights and goods perfectly just in a whole society and yet everyone could be miserable because they failed to understand how to achieve inner welfare.

Maybe if we organized societies better, everyone would be happier. That is certainly worth trying, but we must also remember the value of freedom. Aldous Huxley’s 1931 novel Brave New World presents as a dystopia a future in which pharmaceuticals, sexual promiscuity, and efficient production have maximized happiness but thereby robbed people of the value and satisfaction that comes from having to struggle as independent and free actors. Free people choose diverse paths and set diverse priorities, some of which lead them to unhappiness. If we honor freedom, then we will be hesitant to make people happy at the cost of their freedom. This is why, in liberal democracies, happiness is not usually seen as a political objective. A government probably cannot make people happy and may threaten their liberty if it tries. The same is true of a parent within a family unit and a boss in a workplace. Each of these have real but limited responsibility for others’ happiness.

Some authors have argued that the only thing to worry about is our own inner wellbeing. A strong example is Epictetus. This major Stoic was born around 55 CE as a slave: his name means “purchased.” He was disabled, perhaps because of a master’s violence. Later in life, he was sent into exile. Yet he became a byword for virtue among both pagan philosophers and early Christians. His core insight was that accidents like disease, enslavement, and exile need not affect your happiness. You can divide all matters into those over which you have control (your own desires, emotions, and private thoughts) and those that are beyond your control (not only disease, suffering, and death but also worldly riches and success). You can learn to care only about the things that you control and can put them in perfectly good order. For instance, you can come to care only about having virtuous intentions, and you can learn to accept whatever happens outside your mind. “Don’t seek for things to turn out as you wish, but wish for them to turn out as they do, and then you will get on well.” [Enchiridion 8] Similar ideas have been worked out in Buddhist and Hindu traditions.

I think his view has two severe drawbacks. First, it reflects an unrealistic psychology. We are evolved, natural creatures. We evolved to be psychologically vulnerable to other people’s treatment. We cannot control our desires and responses to the degree that Epictetus suggests. For instance, it is beyond most people’s capacity to be happy when subjected to abuse or when abandoned and neglected. In fact, we could say that human beings are so constituted that we need other people to take care of us and that we must take care of ourselves. That is why living a good life requires having (and acting upon) the best possible ideas about your inner life and your relations to others.

Second, even when other people are able to make themselves fully happy, we must still be concerned about justice. For instance, if I were to encounter an advanced Buddhist sage who genuinely did not suffer even slightly when I stole his rice bowl, I would still be wrong to take it from him. Epictetus would agree so far; he is against mistreating our fellow human beings. But justice is more than refraining from harming people. I am also obliged to worry about whether other people are stealing food–and whether they have enough to eat in the first place. In other words, a good life includes concern for social justice: for the design, improvement, and maintenance of whole systems. That requires forming desires about the way society is organized and acting to realize those desires–in a word, it requires “politics.” But politics belongs to the category of things that we cannot control, things that are governed by other people’s wills and by fate. Just like making plans to be rich or popular, forming plans to improve a society exposes us to failure and disappointment.

Epictetus advises against political engagement.

You can become invincible if you enter no competition that is not in your power to win. When you see someone honored above others or able to do many things or otherwise admired, do not be carried away by the appearances and consider him blessed/happy. For if the essence of the good lies in what we can achieve, then there is no space for ill-will or jealousy. Rather, for yourself, don’t strive to be a general or an office-holder or a leader/consul, but to be free. The only road to that is contempt for things not in your power [XIX].

But the world needs the modern equivalents of generals, senators, and consuls, plus managers and committee chairs and active members of all kinds of groups. To be an active citizen is part of a good life–if not for all human beings, then at least for many. And that requires being concerned about justice to others as well as your own inner wellbeing.

The sorrows of Pandora’s Box fall into three categories. Some forms of suffering happen to human beings because of the kinds of creatures we are. We can postpone death, aging, disease, pain, and fear, but they are inevitable. Our very existence requires the death of other people, or else the earth would be too crowded for the living. Modern science asserts that we can mitigate these sources of suffering. For instance, we may not be able to cure mortality but we can medicate to reduce pain, anxiety, and other adverse mental states. Stoics and some Buddhists would counsel that we can take the sting out of the same adversities by disciplining our emotional reactions. I am not sure that either strategy can fully succeed.

A different set of injustices are miseries for which we rightly blame our fellow human beings. For instance, we oppress each other politically, exploit each other economically, and exclude each other socially. And even if we are not guilty at a given moment of any of those sins of commission, we may be guilty of grievous sins of omission. I am failing right now to help people even though I own superfluous resources.

The third category is a failure to flourish, thrive, enjoy, and achieve equanimity or satisfaction. Addressing this third category requires focusing inward, on our own moral commitments and beliefs, and seeing if we can improve them to make ourselves happier. Insofar as we can help other people with that task, one of the best ways may be to set a good example.

In short, your happiness should not be your only concern, but it should be one of your concerns.

Happiness is complicated

Much valuable research is being conducted today on the causes and conditions of happiness. Traditionally focused almost entirely on distress and pathology, the discipline of psychology is now turning to positive states and trying to learn what causes them. Meanwhile, economics is moving away from the simplistic premise that the purpose of an economy is to generate wealth and is beginning to conceive of a successful economy as one that makes people happy. The findings of happiness psychology and related research in economics tend to confirm what ancient Stoics, Skeptics, Epicureans and Buddhists advised.

For instance, people seem to gain happiness by being deeply immersed in a purposeful current activity, instead of thinking about the past or the future and instead of doing things that might seem pleasurable but that lack purpose. Acknowledging precedents in Eastern philosophy, the psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi recommends “flow,” or single-minded immersion in an activity over which we have control. Note that flow comes from activity, not from passive experience.

Another source of happiness is caring relationships with fellow human beings. Most people are happier when they feel they contribute to worthwhile communities. That doesn’t mean that highly social people necessarily avoid being depressed. The psychologist Corey Keyes disputes the assumption that people fall on one continuum from depression to happiness (where the latter is defined as a lack of depression). Keyes’ survey research finds that the depression/happiness spectrum exists, but there is a second spectrum as well. This second continuum ranges from “languishing” to “flourishing,” where flourishing encompasses positive emotions, positive psychological functioning (such as believing that your life has purpose, or having warm and trusting relations), and positive social functioning (which includes positive beliefs about other people, confidence that one’s own daily activities are useful for others, and belonging to a community). “Languishing” is basically the absence of flourishing.

Since the flourishing/languishing scale is distinct from happiness/depression, it is possible to be depressed and flourishing. In fact, Keyes movingly discloses in public talks that he fits in that quadrant, being clinically depressed and also flourishing. His findings are important because flourishing brings powerful benefits. For example, it reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease to roughly the same degree as not smoking does. Although languishing is different from mental illness, languishing is bad for your mental health in the long run. In fact, your odds of suffering a diagnosed mental illness later on are just as bad if you are languishing now as if you have a mental illness now. If you would like to be free of mental illness in a few years, it’s just as important to start doing purposeful good work for others as it is to treat your depression or anxiety.

Another finding is that anger and resentment are very bad for happiness, and the best remedy is genuinely to forgive and feel empathy for the person who is the source of anger.

These and other findings from empirical psychology are worth knowing. However, I would not literally commit myself to them as maxims, for four large reasons.

First, they are based on statistical research into large numbers of human beings. Individuals differ. Although there is a general tendency for people to have better inner lives when they care for others, that may not be true for all. There may be genuine introverts who are happiest alone, and also psychopaths who are happiest when they harm others. Even if you are neither an introvert nor a psychopath, you are still unique, not a statistical mean, and so it requires introspection and experience to determine what makes you happy.

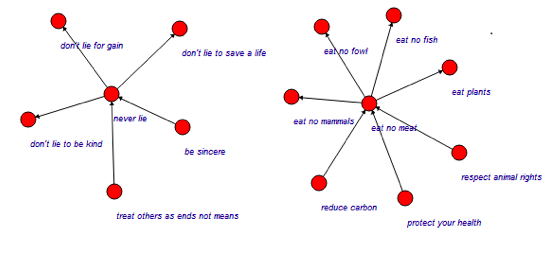

Second, these findings are very vague and general. “Immerse yourself in a meaningful current activity” is a succinct statement of a valid general principle. But at least for me, it would have little force because I know that I can only immerse myself in some kinds of activity, at some times, for some purposes. Moreover, each of these activities has limitations, costs, tradeoffs, and risks. The kinds of principles that seem worthy of endorsement are much more specific and qualified than the general maxim to “pursue flow.”

Third, other people are intrinsically involved. You can’t, for instance, feel confident that your own daily activities are useful for others (one of Keyes’ components of flourishing) unless you are actually responsive to other people’s needs and interests. What they need and want varies and should influence you. There can also be genuine sources of happiness that should be tempered or even avoided because they are not fair to other people. For instance, when I am thoroughly absorbed in a creative activity, I experience “flow,” but I am not being a very good parent, spouse, colleague, or citizen. Although life provides sufficient time for a bit of both, I don’t want to commit to “flow” without acknowledging the tradeoffs for other people.

Finally, these psychological findings are about inputs (experiences, activities, or commitments) and the positive mental states that result. For instance, if you forgive other people, you will be less angry and less subject to stress. If you immerse yourself in the present, you will be happier. Those are causal hypotheses. They beg the question of what outcomes we should want. It is not self-evident that we should want to be happy. At best, that vague term needs to be spelled out in more detail. Are we after calmness and acceptance? Excitement and intense positive experience? Satisfaction? Passion? These are complex and controversial topics, and the science of psychology cannot answer them. It can advise about how to get the various outcomes but not which ones to pursue. In short, inner wellbeing requires analysis as well as explanation. We cannot just decide to attend to our own happiness. We must reason about what our inner life should be like.

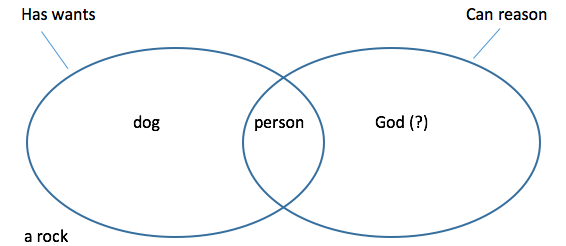

Imagine that the only thing that mattered was how we scored on one simple scale from intense pleasure to intense pain. Then attending to our inner welfare would be a matter of moving ourselves up the scale as far as we could go at any point. But, as Robert Nozick noted in Anarchy State and Utopia, we would not choose to be hooked to an “experience machine” that kept us permanently at the top end of the pleasure scale. Why not? Presumably because happiness–so defined–is not what we want, or to put it another way, the maximization of pleasure is not true happiness. The word that is usually translated as “happiness” from ancient Greek–eudaimonia–has complex meanings and associations, but it is closer to actively and intentionally flourishing than to feeling pleasure.

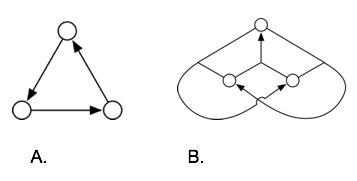

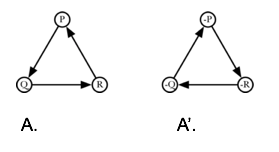

If we do not want to have as much pleasure as possible all the time, then what do we want for our inner lives? The answer may include some combination of pleasure, satisfaction, enjoyment, peace, equanimity, acceptance, hope, purpose, and passion, to name just some desirable mental states. Some of them go neatly and comfortably together. For instance, it could be that equanimity requires acceptance; then those two nodes are linked with an arrow. But some of these concepts are at least potentially at odds. To have purpose and passion may be incompatible with acceptance. Hope is a virtue in Christianity but not in classical Greek or Buddhist thought, which view hope as naive and inconsistent with equanimity.

Modern academic philosophy in the countries strongly influenced by the West is not especially focused on getting these ideas in good order. It attends more to ethics (in the sense of treating other creatures right) and social justice (organizing a social system fairly) than to inner wellbeing. In 1958, Elizabeth Anscombe noted and lamented that omission. “It can be seen” she wrote, “that there a huge gap, at present unfillable as far as we are concerned, which needs to be filled by an account of human nature, human action, the type of characteristic a virtue is, and above all of human ‘flourishing.’” To the extent that matters have improved since 1958, that is because academic philosophers in countries like the US and Britain have revisited authors from earlier traditions, notably the pre-Christian Greeks, the classical Asian thinkers, and subsequent works under their influence. Owen Flanagan argues that Buddhism and “Western” philosophy have compensating weaknesses and advantages. Buddhism gives rich and detailed accounts of the inner life but fails (as yet) to provide satisfactory accounts of social justice, especially in complex modern societies composed of states and markets. Western philosophy offers much weaker and more cursory accounts of the good inner life. We must put the pieces back together.

See also: Mill’s question: If you achieved justice, would you be happy?; on philosophy as a way of life; Emerson’s mistake.