Participatory Budgeting has been rapidly growing across the world for the last 30 years, in all levels of government, in organizations, and in schools. There was a report released by the Hewlett Foundation and Omidyar Network on the current state of PB and its future; and NCDD member org, the Participatory Budgeting Project, recorded a webinar with the report authors, Stephanie McNulty and Brian Wampler. You can listen to the webinar in the article below and find the original on PBP’s site here.

Lessons from 30 years of a global experiment in democracy

The Hewlett Foundation and Omidyar Network recently funded a major new report on the lessons learned from 30 years of participatory budgeting (PB). In July, we hosted a webinar about the state and future of PB with report authors Stephanie McNulty and Brian Wampler.

Check out the webinar recording, slides, and key takeaways below.

We asked Stephanie and Brian about what it meant to write this report in 2018, a time of great change for PB and for democracy.

Stephanie spoke to how PB has grown since beginning in Brazil in 1989: “It’s sort of exploding, and happening all over the world in places that are very different from Brazil… It’s taking place faster than we can document and analyze.”

Brian shared about experimentation in PB happening with a variety of focus areas and in new contexts. Part of the power of PB is in how adaptable it is. Many folks experiment with how to design PB to best serve their community. And so, PB looks different in the more than 7,000 localities it exists in around the world.

“PB is probably the most widespread public policy tool to undertake what we consider democratizing democracy.”- Stephanie McNulty

In 30 years, PB has created significant impacts. Doing PB and studying it need more investment to further impact democracy. We’re still learning about the ways that PB can transform individuals and communities.

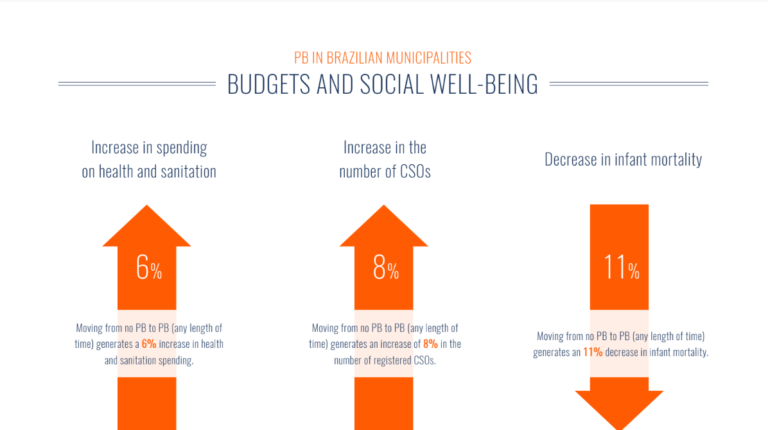

Early research suggests PB strengthens the civic attitudes and practices of participants, elected officials, and civil servants. Beyond changes at the individual level, the report documents changes at the community level. Changes at the community level include greater accountability, stronger civil society, improved transparency, and better well-being.

But, in the end, good PB doesn’t just happen; it has to be built. It requires intentional effort to ensure that PB practice lives up to its promise. It can yield benefits for those who participate in the early stages, but it takes time for those to expand to broader areas. PB is growing faster as more people learn about it’s potential. We need further research to learn from what advocates on the ground know about PB’s impact—as well as it’s areas for improvement. The future of PB will require effort and sustained resources to support new ways of placing power in the hands of the people.

The report documents key ways PB has transformed over 30 years.

- Scale. PB started at the municipal level in Brazil, and now exists in every level of government, and even within government agencies. PB is now being done for schools, colleges, cities, districts, states, and nations—places where people are looking for deeper democracy.

- Secret ballots to consensus-based processes. When we spoke about what was most surprising or unexpected while writing the report, Brian talked about the shift in how communities make decisions in PB often moving from secret ballots to consensus-based processes.

- Technology. New technologies are used for recruitment, to provide information, and to offer oversight. We don’t fully understand the benefits and limitations of this particular transformation, and look forward to more research on this question.

- Increased donor interest. More international donors are interested in promoting and supporting PB.

- A shift away from pro-poor roots. PB in Brazil began as a project of the Workers Party to pursue social justice and give power to marginalized communities and the disenfranchised. This is a core reason why many look to PB to solve deeply entrenched problems of inequity in the democratic process. Unfortunately today, many PB processes around the world do not have an explicit social justice goals.

We’ve learned that focusing on social justice actually makes PB work better. PB processes that seek to include traditionally marginalized voices make it easier for everyone to participate in making better decisions.

To wrap up our webinar, Laura Bacon from Omidyar Network, David Sasaki from the Hewlett Foundation, and our Co-Executive Director at PBP, Josh Lerner shared takeaways for grantmakers.

They discussed what we need to make the transformative impacts of PB be bigger and more widespread.

Medium and long term investment is important for PB success. One off investments don’t create the impacts of PB and can lead to a decline in quality.

Medium and long term investment is important for PB success. One off investments don’t create the impacts of PB and can lead to a decline in quality.- Government support is crucial. PB works best when it complements government—not opposes it.

- Watch out for participation fatigue. If the conditions for successful PB are not fully in place, residents and advocacy organizations can grow weary of continued involvement.

- Funders should focus PB grantmaking in areas that have conditions in place for it to be successful. They should look at political, economic, and social contexts before funding the process.

Want more updates on the state and future of PB? Sign up for PBP’s Newsletter

You can find the original version of this article on the Participatory Budgeting Project site at www.participatorybudgeting.org/lessons-from-30-years-of-pb/.