Scott Alexander has an interesting blog post that distinguishes two ways of thinking about politics:

- “Politics as mistake.” I’d put this one a little differently. The core idea is that institutions have flaws that result from their designs and the incentives that they create for participants. Sometimes institutions work well enough, but we use the word “politics” for efforts to fix them. Political action is driven by a belief that the structure and incentives of existing institutions demands change.

- “Politics as conflict”: Here the idea is that different people have different interests and ideals, so it matters who’s in charge. Politics is mostly about putting one’s own side in control of institutions.

Alexander’s post is long and I could argue that it’s a bit tilted in favor of #1, partly because the examples he cites of #2 are unnecessarily tendentious, e.g., a Baffler article on James Buchanan. Very serious people from a range of perspectives agree with #2. Still, even with a possible tilt, I find Alexander’s framework useful.

The poster child for #1 would be China. The Communist Party took control in 1949, representing a demographic group (workers and peasants) and an ideology (state communism). A fairly continuous group of leaders still runs that Party and that country. For instance, the current premier, Xi Jinping, is the son of the Party’s former propaganda chief, vice-premier, and National People’s Congress vice chair (1952-62). But the regime has shifted from radically egalitarian to rapaciously capitalist, and many grandchildren of Red revolutionaries are billionaires. I make sense of this story by discounting politics as conflict. It doesn’t matter who runs the government or what they stand for. Structures and incentives ultimately prevail. If single-party government gives the ruling cadre a chance to rack up billions, they will sooner or later rack up billions.

Roberto Mangabeira Unger has unimpeachable leftist credentials, but he faults the 20th century left for ignoring institutional structures and the incentives they create. “With few exceptions (such as the Yugoslav innovations),” he writes, “the radical left … has produced only one innovative institutional conception, the idea of the soviet or conciliar type of organization: that is to say, direct territorial and enterprise democracy.” But soviets were never seriously developed to address “practical problems of administrative and economic management,” and they have “quickly given way to forms of despotic government” (False Necessity, pp. 24-5).

On the other hand, politics as conflict (#2) makes better sense of “realignment” elections in functional democracies. When FDR won the presidency in 1932, or when the British Labour Party won in 1945, new people with new interests and new ideas took over those countries. The result was a raft of new policies and institutions. When Thatcher and Reagan won elections decades later, they reversed some of those policies and began to dismantle some of those institutions. It matters who wins the support of the majority of voters and what program they propose.

The same debate also arises in specific domains of policy. For example, people who believe in politics as conflict think that the key questions for education are what is taught and how. There are lively debates between whole language and phonics, patriotic and critical versions of American history, STEM and the humanities. To influence the outcome of these debates, we can try to persuade teachers and schools to adopt our vision of education. We can also enact favorable policies, such as legislative mandates to teach or assess in certain ways.

Meanwhile, some people believe that the important questions in education concern structures and incentives. Maybe we must pay teachers more and protect their autonomy, or assess student outcomes and hold teachers accountable, or give parents choice and let dollars flow to the schools that they choose. These are politically and ideological contrasting theses, but all presume that the way to improve education is to get the incentives right.

It’s too easy to say, but I believe it: politics is both institutional design and conflict over ideas and interests, and each aspect requires attention. Unger recommends that reformers “develop elaborate institutional incentives, a strategy for putting them into effect, and a view of social transformation to inform both their programmatic and their strategic ideas. They must also redefine their guiding ideals and their conceptions of the relation of these ideals to the aims of their political opponents. For if the real meaning of an ideal depends upon its tacit institutional background, a shift in the latter is sure to disturb the former” (pp. 20-21).

It’s a mistake to ignore incentives and assume that institutions will do what they officially promise, unless that somehow pays off for the people in charge. To assume that public schools will serve every child is like assuming a can-opener on a desert island. (Or assuming that a dictatorial party will pursue equality just because it calls itself “communist.”) But it’s also a mistake to discount ideas and ideals or to presume that the only payoffs that people care about are monetary. For the purpose of explaining social change, both incentives and ideals have power.

Further, if you want to know whether you are changing the world for the better, you must rely on a range of evidence. It’s useful to observe people’s behavior under constraints. For example, price signals tell you what people value, given what they have. That kind of analysis falls under Alexander’s “politics as mistake” heading (although the word “mistake” is a bit misleading; it’s really politics as engineering). However, evidence from behavior is always insufficient, because you must also decide what means and ends are good. Unless you arrogantly assume that you can answer that question by yourself, you must listen to other perspectives. And that necessitates “politics as conflict.”

See also how to tell if you’re doing good; the visionary fire of Roberto Mangabeira Unger; school choice is a question of values not data.

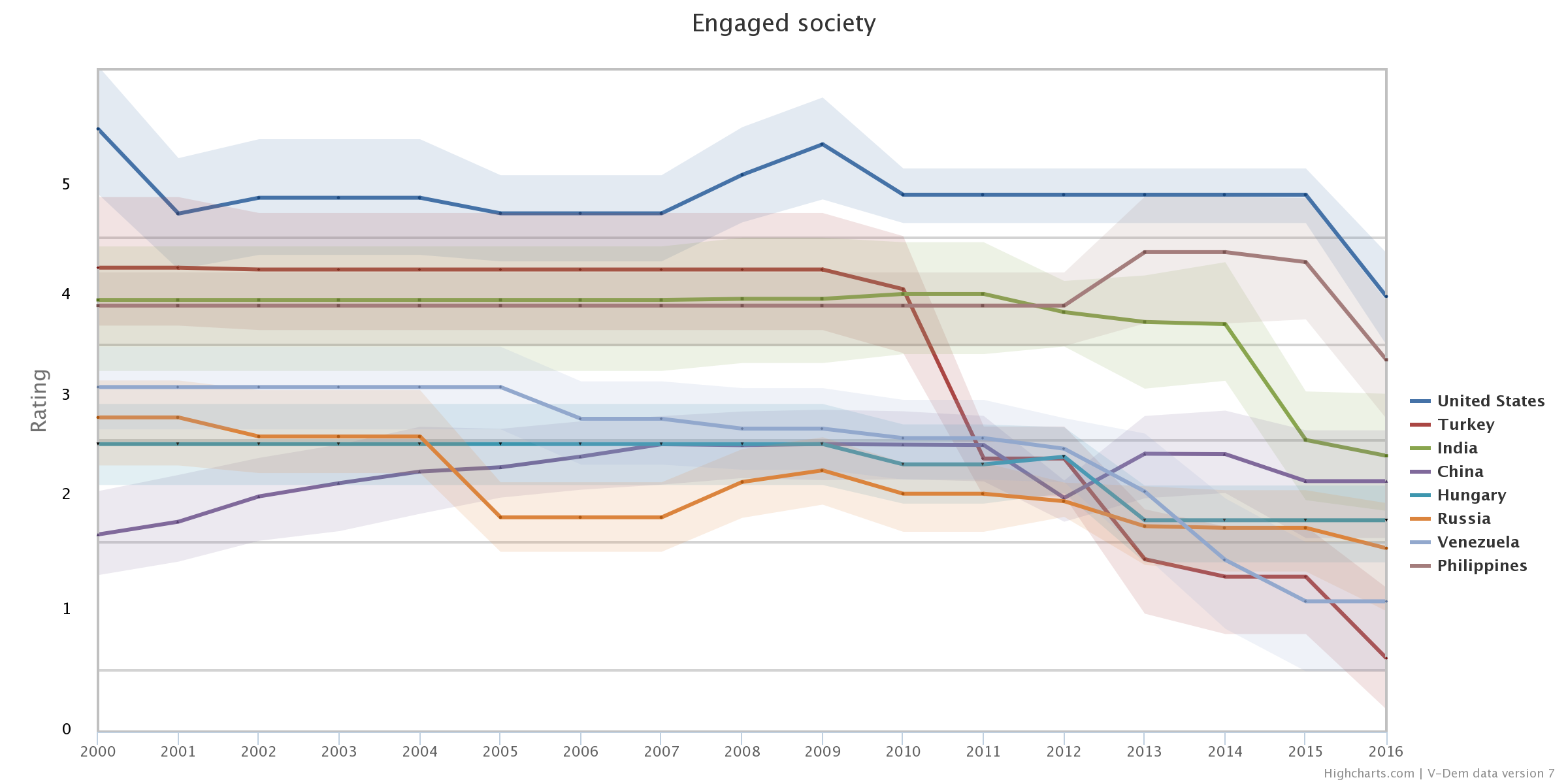

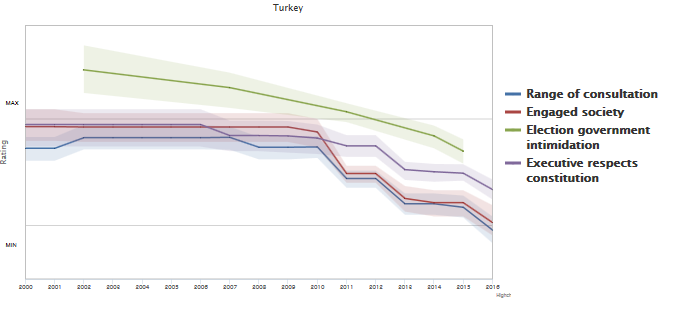

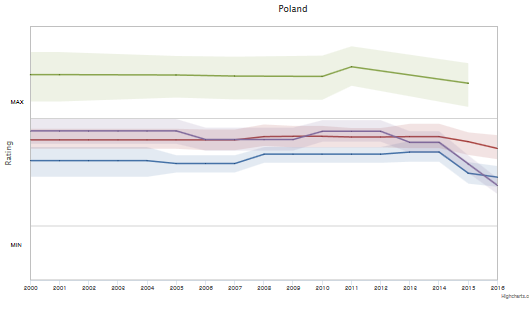

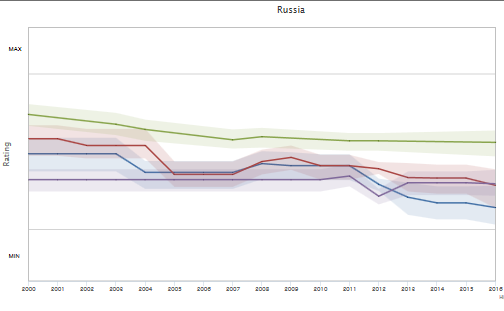

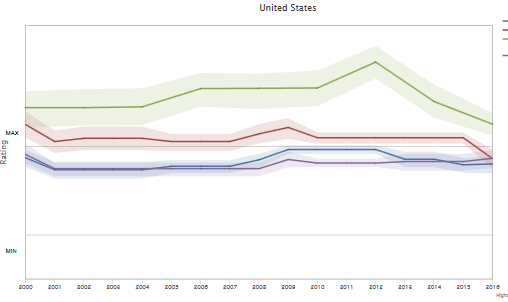

The pattern is less pronounced but similar in Poland since 2011.

The pattern is less pronounced but similar in Poland since 2011.

Róbert Bjarnason, from the nonprofit

Róbert Bjarnason, from the nonprofit  Tech Tuesdays are a series of learning events from NCDD focused on technology for engagement. These 1-hour events are designed to help dialogue and deliberation practitioners get a better sense of the online engagement landscape and how they can take advantage of the myriad opportunities available to them. You do not have to be a member of NCDD to participate in our

Tech Tuesdays are a series of learning events from NCDD focused on technology for engagement. These 1-hour events are designed to help dialogue and deliberation practitioners get a better sense of the online engagement landscape and how they can take advantage of the myriad opportunities available to them. You do not have to be a member of NCDD to participate in our