Monthly Archives: January 2017

Demographic bias in social media language analysis

Before the break, I had the opportunity to hear Brendan O’Connor talk about his recent paper with Su Lin Blodgett and Lisa Green: Demographic Dialectal Variation in Social Media: A Case Study of African-American English.

Imagine an algorithm designed to classify sentences. Perhaps it identifies the topic of the sentence or perhaps it classifies the sentiment of the sentence. These algorithms can be really accurate – but they are only as good as the corpus they are trained on.

If you train an algorithm on the New York Times and then try to classify tweets, for example, you may not have the kind of success you might like – the language and writing style of the Times and a typical tweet being so different.

There’s a lot of interesting stuff in the Blodgett et al. paper, but perhaps most notable to me is their comparison of the quality of existing language identification tools on tweets by race. They find that these tools perform poorly on text associated with African Americans while performing better on text associated with white speakers.

In other words, if you got a big set of Twitter data and filtered out the non-English tweets, that algorithm would disproportionally identify tweets from black authors as not being in English, and those tweets would then be removed from the dataset.

Such an algorithm, trained on white language, has the unintentional effect of literally removing voices of color.

Their paper presents a classifier to eliminate that disparity, but the study is an eye-opening finding – a cautionary tail for anyone undertaking language analysis. If you’re not thoughtful and careful in your approach, even the most validated classifier may bias your data sample.

Engaging Ideas – 1/13/2017

the hollowing out of US democracy

How could a celebrity with no governing experience and no grassroots infrastructure alienate and offend an outright majority of Americans, adopt positions far from the mainstream, and yet become our president?* I argue that the underlying reason is a hollowed-out democracy in which many citizens no longer expect to be represented by accountable organizations and are no longer invited to share in governing. A celebrity who offers symbolic politics has the number of followers and the level of attention that professional politicians strive to buy with their cash. In an environment of isolated citizens, he wins.

We still have plenty of voluntary associations and networks concerned with politics. But politics is a minority taste, so these groups draw a small proportion of the population. And because most of them attract members by offering a political message or agenda, they produce ideologically homogeneous groups.

We also still have very large numbers of professional advocacy organizations, but many of them are accountable to donors rather than members, and their capacity and vision come from their highly-skilled professional staff, not from citizens.

We also have some large movements that look accountable but aren’t. The Koch Brothers network, for example, employs 1,200 full-time, year-round staffers in 107 offices nationwide, more than the Republican Party. The Koch Brothers own it.

What we lack now are the kinds of organizations that I believe have been core to US civil society since the era of de Tocqueville. They offer benefits other than politics to attract members. They draw a range of people–not representative samples of the US population, but diverse groups. They give their members reasons to think politically and aggregate their political power. They create pathways to political leadership for those who become most interested. And they depend on their members’ support for survival.

In short, they offer what I’d call SPUD–Scale, Pluralism, Unity, Depth–which is the magic recipe for civic engagement.

Four traditional types of organizations that offered SPUD were unions, political parties dependent on local voluntary labor, religious congregations, and metropolitan daily newspapers. All four were imperfect, but each was much better than nothing. And they are all in bad shape today.

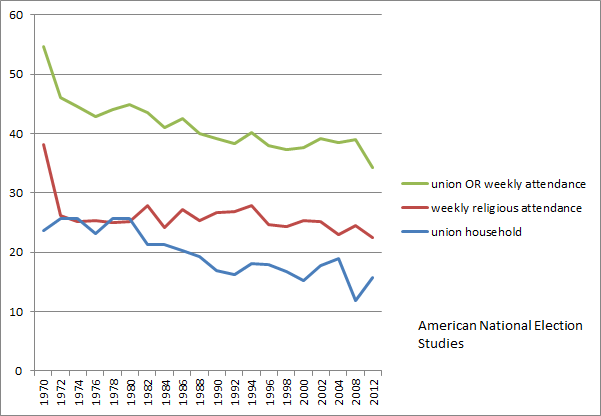

I’ve previously shown that newspapers have lost readership precipitously and parties have become loose networks of entrepreneurial politicians and donors instead of actual organizations. Unions and religious congregations have also shrunk. To illustrate those two trends, here is a new graph that shows the rates of union membership and weekly religious attendance. The top line is the proportion of adult Americans who either attend weekly services or belong to a union, or both. That proportion has dropped by twenty points, from a majority of 54.6 percent in 1970 to a minority of 34.3 percent in 2012. (By the way, I am skeptical that union membership really rose in 2012; I suspect that’s random noise.) I would look no further than this 20-point drop for the underlying conditions that yielded The Donald.

*The echo of Hamilton was inadvertent but seemed apt once I noticed it.

NCDD’s Year in Numbers: 2016

2016 was an important year for the dialogue & deliberation community, and a very active one for NCDD!

The following end-of-year infographic highlights NCDD’s impact and activity during the past twelve months, including activity at our national conference, on our website, listservs, events, and new and exciting efforts. Our sincere thanks to NCDD co-founder Andy Fluke for his fabulous design work!

Thanks to our fabulous community for engaging with us in so many ways in 2016! We look forward to continuing this important work with you all in 2017.

Please share this post with others you think should know there’s an amazing community of innovators in public engagement and group process work they can tap into or join!

In addition to sharing this post and/or just the image above, feel free to download the print-quality PDF.

Conto Partecipo Scelgo. Il Bilancio partecipativo del Comune di Milano [Milan Participatory budget]

Bringing Community College Faculty to the Table

Workshop: Public Engagement Strategy in Sacramento

The Knowledge Economy and (Ab)use of Symbols

I’m taking a Network Economics class this semester, and we’ve reasonably begun by reading The Use Knowledge in Society – in which Hayek addresses the economic problem of information scarcity.

The economic problem faced by society, Hayek argues, is that “the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form, but solely as dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess.” That is, the problem is “how to secure the best use of resources known to any members of society, for ends whose relative importance only these individuals know.”

Hayek, of course, sees this problem as one which is best solved by the free market – by decentralization of economic decisions. On its face, his argument makes a lot of sense: “If we can agree that the economic problem of society is mainly one of rapid adaptation to changes in the particular circumstances of time and place, it would seem to follow that the ultimate decisions must be left to the people who are familiar with these circumstances, who know directly of the relevant changes and of the resources immediately available to meet them. We can’t expect that this problem will be solved by first communicated all this knowledge to a central board which, after integrating all knowledge, issues its orders. We must solve it by some process of decentralization.”

There is a lot of Hayek’s argument that I agree with. In the civic space, we often talk about the danger of expertise – technical knowledge is valuable and important, but reducing a community problem to a technocratic solution overlooks the expertise of the people themselves. No expert, no matter how well educated, can parachute into a community they know nothing about and successfully solve it’s problems without engaging community solutions.

But I don’t follow Hayek’s jump – just because a purely technocratic solution is clearly bad it does not necessarily follow that a purely populist solution is therefore good.

Hayek praises the pricing system of the open market as a mechanistic marvel – as an emergent behavior which continually tends towards the equilibrium of an instantaneous time and context. In other words, pricing becomes a tool for coordination, a “mechanism for communicating information.” It operates as “a kind of symbol” ensuring that “only the most essential information is passed on and only to those concerned.”

This is a inspiring description of market pricing, but it obscures the problems with such an approach – namely, it is unclear just how much people know and how much of that information is accurate.

Hayek’s invocation of ‘symbols’ immediately makes me think of Lippmann’s work – symbols can be powerful tools for coordination, but they are also props for propaganda and manipulation.

John Dewey describes the positive impact of symbols, writing, “Events cannot be passed from one to another, but meanings may be shared by means of signs. Wants and impulses are then attached to common meanings. They are thereby transformed into desires and purposes, which, since they implicate a common or mutually understood meaning, present new ties, converting a joint activity into a community of interest and endeavor. Thus there is generated what, metaphorically, may be termed a general will and social consciousness: desire and choice on the part of individuals in behalf of activities that, by means of symbols, are communicable and shared by all concerned.”

The problem, as Lippmann points out, is that elites are too easily able to manipulate those signs and symbols – to manufacture a shared experience and expectation which comes, not truly from the knowledge possessed by individuals, but which are myths designed solely to fulfill elite’s goals.

Promoting Inclusion, Equity and Deliberation in a National Dialogue on Mental Health

The 15-page article, Promoting Inclusion, Equity and Deliberation in a National Dialogue on Mental Health, was written by Tom Campbell, Raquel Goodrich, Carolyn Lukensmeyer, and Daniel Schugurensky, and published in the Journal of Public Deliberation: Vol. 12: Iss. 2. In the article, the authors share their experiences with the project, “Creating Community Solutions” (CCS), in which six organizations partnered to better understand how the public is engaged around mental health. By implementing three engagement strategies, CCS sought to shift the social norms around mental health and work to improve the inclusivity of how individuals and communities are engaged.

Read an excerpt of the article below and find the PDF available for download on the Journal of Public Deliberation site here.

From the article…

The ability to make progress on the nation’s mental health crisis has been limited not only by inadequate resources but also by the difficulty of addressing underlying discrimination, stigma, and cultural barriers. Indeed, some populations are especially vulnerable and underserved by mental health services. To begin, young people have high rates of mental health problems and low rates of seeking help; three-quarters of mental health problems begin before the age of 24. Second, common mental health disorders are twice as common among individuals with low incomes, and there is a strong correlation between mental illness, poverty, and crime. Third, communities of color tend to experience a greater burden of mental and substance-use disorders, most often due to limited access to care, inappropriate care, and higher social, environmental, and economic risk factors. Fourth, LGBTQ youth are sometimes rejected by their families and peers, and experiencing bullying and bias can lead to anxiety, depression, drug use, and suicide. The stigma associated with mental illness often leads to reluctance to find help. It has been reported that up to 60 percent of individuals with mental illness do not seek treatment and services (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015).

The scarcity of safe environments in many communities to acknowledge mental health challenges and to address them systemically has limited the ability to create new solutions. Prior efforts to engage marginalized populations in mental health deliberations have not always shown positive results. For instance, in a study on the engagement of mental health service users/survivors in deliberative democracy, Barnes (2002) examined how notions of “legitimate participants” were constructed within official discourse and argued that the emphasis on rational debates could have excluded the emotional content of the experience of living with mental health problems from deliberation about mental health policy. A related study, conducted by Hughes (2016), on a deliberative system that connected federal policymakers with the disability community found that the discourse of the government agency failed to engage with social difference as a resource for inclusion and collaboration, reinforced stigma around disability, and excluded underrepresented groups. In this context, the project “Creating Community Solutions” (CCS) aimed to change social norms around mental health, reduce discrimination, and bring forward more inclusive opportunities for community engagement. Gastil (2014) contended that scholars in the field of public deliberation must produce not only rigorous research but also field reports that help reformers and public officials refine their methods of public engagement. By discussing CCS and its three engagement strategies, we hope to provide useful information and insights to public officials and practitioners interested in large-scale, solution-oriented public engagement projects.

Blending Deliberative Methods and Designing for Inclusion

Led by the National Institute for Civil Discourse, six deliberative democracy organizations partnered to launch Creating Community Solutions (CCS). A unique aspect of this project was the willingness and ability of the six organizations to collaboratively design the initiative using the strengths of each one to reach communities and to take the program to a national scale. The design included three main strategies. The first was Lead Cities, with mayor-initiated, in-depth deliberative conversations using town hall meetings and neighborhood outreach in six cities. The second, Community Conversations, varied in length and were held in every state in the country. The third, Text Talk Act, used text messaging as a method to get young people talking about mental health. Common to all strategies was a consistent set of topics and questions, a website with supporting resources, outreach into neighborhoods and affected populations to include individuals not traditionally part of the mental health system, and a prioritization process for developing recommendations to respond to mental health challenges.

The three strategies relied on small group discussions facilitated by discussion guides and other materials. These materials included factual information on mental health problems, challenges to key cultural populations, the importance of early identification and treatment, and key questions related to the mental health field. While the larger town hall meetings brought a more representative sample of the local population and generated longer conversations, the addition of community conversations and texting platforms enabled CCS to create more inclusive participation of various segments of the population and to achieve a national reach. Indeed, CCS wanted to build a nationwide conversation but also sought to approach it in a way that would allow voices not normally heard in the discussion of mental health to be considered and acted upon. This effort was guided by three main goals. The first was to reach deeply into selected lead cities with an outreach process that included a representative sample of the population and an oversample of youth and affected communities. The second was to reach broadly across the country by supporting community initiatives to ensure that conversations were held in every state. The third was to reach young people directly by utilizing their preferred communication practices through a readily accessible texting platform.

These strategies were relevant because conversations on mental health often attract the “usual suspects.” In many situations, stakeholder groups are among the first to sign up and take a prominent role, especially if they know that a national audience and local leaders are listening. While the design team understood that providers and experienced stakeholders would want to attend, CCS limited the number of mental health providers and registered participants to ensure a representative sampling of the demographics of the whole community. Through extensive outreach and the use of a questionnaire in the registration process, organizers were able to monitor the representative nature of the participants and achieve a truly community-wide conversation to hear how ordinary citizens wanted to see the system changed. As Michels (2011) noted, inclusion is often best achieved by engaging citizens through social networks, providing open access to forums, and striving to attract participants who are representative of the community as a whole.

Download the full article from the Journal of Public Deliberation here.

About the Journal of Public Deliberation

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen friendly form.

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen friendly form.

Follow the Deliberative Democracy Consortium on Twitter: @delibdem

Follow the International Association of Public Participation [US] on Twitter: @IAP2USA

Resource Link: www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol12/iss2/art8/