Monthly Archives: January 2017

why Trump fans aren’t holding him accountable (yet)

(Washington DC) Kevin Drum imagines how a Trump fan receives the president’s tweets:

You’re at home, watching the Factor, and O’Reilly is going on about the crime problem in Chicago. It’s outrageous! The place is a war zone! Somebody should do something!

Then, a few minutes later, you see Trump’s tweet. “If Chicago doesn’t fix the horrible “carnage” going on, 228 shootings in 2017 with 42 killings (up 24% from 2016), I will send in the Feds!” Damn straight, you think. They need the National Guard to set things straight there. Way to go, President Trump.

This exchange is good enough for you–on its own. You don’t really want Trump to send the feds into Chicago, whatever that might mean. If it would cost money or create a precedent for federal intervention in your town, or anything like that, you might actually be against it. But your media stream will never give you an update on whether Trump sent in the feds or what happened to the murder rate in Chicago. You are immersed in media that consists largely of bad news about places you don’t like. You are satisfied that the guy in charge shares your opinion and has announced he’s on it. He even quotes verbatim the same stats you just saw on O’Reilly. It’s a magic solution–at last.

I think more or less the same will happen as a result of Trump’s announcement today that Mexico will pay for the border wall via a 20% import tax. That is highly unlikely to occur, because Congress would have to enact the tax, and I’m guessing the economic effects would be awful if it did; but Trump’s fans will probably never get an update. They may hear about battles between the president and Congress over taxes, but those will take the form of specific insults flung from his end of Pennsylvania Ave. up to the Hill, which they will endorse. Each exchange will be an event unto itself.

I happen to think that this kind of politics has yuge political limitations for Trump. Most people already disapprove of him, and his welcome is going to wear even thinner when people’s actual lives fail to improve. In turn, massive disapproval will weaken his already shaky position. But it’s still a very dangerous situation, at best, and is very far from any reasonable model of a democracy.

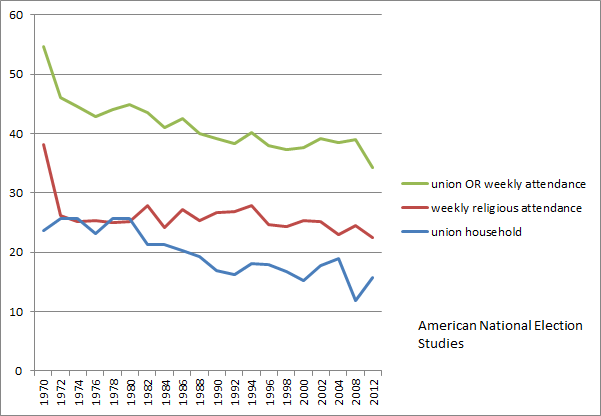

My explanation is that millions of Americans have lost all expectation that leaders will be accountable to them. At the national level, they are not getting very good results from the government that purports to represent them. At the local level, they have lost the kinds of institutions that used to depend on people like them. To reprise a graph from a recent post, here is the trend in the proportion of people who belong to a church and/or a union:

For all their flaws, these are the kinds of institutions that make promises and then have to deliver. If they fail, their members know about it and complain, act up, or walk out. A union or a church has a real covenant with its members. When people have no such expectations of accountability, they are much more likely to be satisfied because the boss just tweeted something they agreed with. Again, I think Trump’s own appeal will wear even thinner than it is now, but the underlying problem is a lack of accountable organizations in many communities.

Demanding Dignity and Respect for All My Neighbors

It’s been a dramatic week. President Trump has signed a number of Executive Orders and Memoranda which strike at the very core of what I believe.

I have been particularly disturbed by two orders signed yesterday; the first on “border security” and the other on “public safety” – phrases which are essentially Newspeak for racial bias and immigrant hatred. “Tens of thousands of removable aliens have been released into communities across the country,” one order claims.

I am ashamed to hear such hateful rhetoric coming from the President of my country.

But I am given hope by the millions of good men and women who don’t accept such false claims; who have worked and who reaffirm their work to supporting and welcoming all members of our community.

In his Order, President Trump claimed that sanctuary cities – those jurisdictions which have refused to enable a Federal witch-hunt for difference, “have caused immeasurable harm to the American people and to the very fabric of our Republic.”

I say that it is these jurisdictions which epitomize the very fabric our Republic. It is these jurisdictions which stand true to American values; who pursue the vision of a land where all people are created equal and endowed with the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

I am proud to live in a Sanctuary city, and I am proud that my mayor, Joseph Curtatone, has said in no uncertain terms that we will not waiver in this commitment. These are our neighbors.

I am also proud to serve as the vice-Chair of the board for The Welcome Project, a vibrant non-profit which builds the collective power of Somerville immigrants to participate in and shape community decisions.

In response to Wednesday’s reprehensible executive orders, The Welcome Project released the following statement this morning. And by the way, you can donate to The Welcome Project here. ___

President Donald Trump signed executive orders Wednesday attacking America’s status as a nation of immigrants. We at The Welcome Project are saddened but steadfast. We will not waiver in continuing the work our communities have entrusted us to do; building the collective power of immigrants to help shape community decisions and pursuing the American vision of liberty and justice for all.

We thank Mayor Curtatone, the Board of Aldermen, and the residents of Somerville as they continue to fight for America and support immigrants, community, and Sanctuary City status. Somerville continues to be a beacon of light and a hope for many. We know that our community only becomes stronger when all people are free to participate in it; that Sanctuary Cities are not about harboring criminals, they are about reducing crime, increasing trust between the police and the community, and offering a better future for our families.

The Welcome Project will continue to work with all members of our community, supporting all immigrants regardless of documentation status. We will stay vigilant in our mission and push for the rights of all. We will work with the immigrant community to ensure their voices are being heard. We will continue our commitment to justice, equality, and inclusion. We thank all of you for your continued support as we explore the effects these executive orders have on our organization, our constituents, and our city.

Benjamin Echevarria

Executive Director

Andreas Karitzis on SYRIZA: We Need to Invent New Ways to Do Politics

This is a time of great confusion, fear and political disarray. People around the world, including Americans afflicted by a Trump presidency, are looking for new types of democratic strategies for social justice and basic effectiveness. The imploding neoliberal system with its veneer of democratic values is clearly inadequate in an age of globalized capital.

Fortunately, one important historical episode illuminates the political challenges we face quite vividly: the protracted struggle by the Greek left coalition party SYRIZA to renegotiate its debt with European creditors and allied governments. SYRIZA’s goal was to reconstruct a society decimated by years of austerity policies, investor looting of public assets, and social disintegration. The Troika won that epic struggle, of course, and SYRIZA, the democratically elected Greek government, accepted the draconian non-solution imposed by creditors. Creditors and European neoliberals sent a clear signal: financial capital will brutally override the democratic will of a nation.

Since the Greek experience with neoliberal coercion is arguably a taste of what is in store for the rest of the world, including the United States, it is worth looking more closely at the SYRIZA experience and what it may mean for transformational politics more generally. What is the significance of SYRIZA’s failure? What does that suggest about the deficiencies of progressive politics? What new types of approaches may be needed?

Below, I excerpt a number of passages from an excellent but lengthy interview with Andreas Karitzis, a former SYRIZA spokesman and member of its Central Committee. In his talk with freelance writer George Souvlis published in LeftEast, a political website, Karitzis offers some extremely astute insights into the Greek left’s struggles to throw off the yoke of neoliberal capitalism and debt peonage. Karitzis makes a persuasive case for building new types of social practices, political identities and institutions for “doing politics."

I recommend reading the full interview, but the busy reader may want to read my distilled summary below. Here is the link to Part I and to Part II of the interview.

Karitzis nicely summarizes the basic problem:

We are now entering a transitional phase in which a new kind of despotism is emerging, combining the logic of financial competition and profit with pre-modern modes of brutal governance alongside pure, lethal violence and wars. On the other hand, for the first time in our evolutionary history we have huge reserves of embodied capacities, a vast array of rapidly developing technologies, and values from different cultures within our immediate reach. We are living in extreme times of unprecedented potentialities as well as dangers. We have a duty which is broader and bolder than we let ourselves realize.

But, we haven’t yet found the ways to reconfigure the “we” to really include everyone we need to fight this battle. The “we” we need cannot be squeezed into identities taken from the past – from the “end of history” era of naivety and laziness in which the only thing individuals were willing to give were singular moments of participation. Neither can the range of our duty be fully captured anymore by the traditional framing of various “anti-capitalisms”, since what we have to confront today touches existential depths regarding the construction of human societies. We must reframe who “we” are – and hence our individual political identities – in a way that coincides both with the today’s challenges and the potentialities to transcend the logic of capital. I prefer to explore a new “life-form” that will take on the responsibility of facing the deadlocks of our species, instead of reproducing political identities, mentalities and structural deadlocks that intensify them.

The Challenge of Populism to Deliberative Democracy

As populism sees a global resurgence, it is critical for our field to examine what this phenomenon means for our work. That’s why we encourage our network to give some thought to the insights offered in this piece from Lucy Parry of Participedia – an NCDD member organization. In it, Lucy examines the way citizens juries in Australia might violate core tenets of populism, and encourage us to consider how deliberative democracy – especially approaches using mini-publics – may need to evolve to avoid being delegitimized by populist challenges. You can read the piece below or find it on Participedia’s blog here.

When is a democratic innovation not a democratic innovation? The populist challenge in Australia

The following article by Participedia Research Assistant Lucy Parry was originally published by The Policy Space on October 11, 2016.

![]() Democratic innovation is burgeoning worldwide. Over 50 examples from Australia alone are now detailed on Participedia, an online global project documenting democratic innovations. In some states, ‘mini-publics’ proliferate at local and state level. South Australia in particular has wholeheartedly embraced the notion of deliberative democracy and has embarked on an ambitious raft of citizen engagement processes including several Citizens’ Juries.

Democratic innovation is burgeoning worldwide. Over 50 examples from Australia alone are now detailed on Participedia, an online global project documenting democratic innovations. In some states, ‘mini-publics’ proliferate at local and state level. South Australia in particular has wholeheartedly embraced the notion of deliberative democracy and has embarked on an ambitious raft of citizen engagement processes including several Citizens’ Juries.

According to Graham Smith (2009) a democratic innovation must (a) engage citizens over organised interests and (b) be part of the wider political process. Mini-publics operationalise these aims through convening a group of citizens who are at least broadly representative of the wider population to deliberate on a given topic.

Despite fulfilling Smith’s criteria, democratic innovations in Australia run the risk of becoming neither democratic nor innovative. Scholarly debate over mini-publics peaked over a decade ago – isn’t it time to move on? Moving on necessitates moving with the times and dealing with contemporary challenges. One such challenge is the rise of populism. Australian democratic innovations typically rely on premises that are fundamentally opposed by populism: random selection and expert knowledge. This populist challenge cannot be ignored, and theorists and practitioners must meet it together.

Inside the room

A Citizens’ Jury is a well-known mini-public format: a small(ish) group of randomly selected citizens who meet several times to deliberate on a given topic. Random selection underpins the process in two ways. It aims to produce a descriptively representative sample, making the jurors literally a ‘mini public’ (Fung 2003; Ryan and Smith 2014): a microcosm of the wider population. Random selection also relates to deliberative quality: bringing together a group of random citizens reduces the likelihood of the loudest voices dominating. As Australian research organisation newDemocracy Foundation points out, ‘governments inevitably hear from the noisiest voices who insist on being heard’; lobbyists, Single Issue Fanatics (SIFs), Not-in-my-back-yards (NIMBYs) – call them what you will. Mini-publics are designed to foster a less adversarial, more nuanced debate with a group of random citizens.

I have observed Citizens’ Juries in the flesh and it is quite an extraordinary experience. Watching a room of disparate and diverse people evolve into a committed team negotiating technical topics like wind farm development leaves me feeling almost jubilant (I don’t get out much). When you are inside the room, watching the deliberative process at play, it really is wonderful. Australia is home to a number of practitioners including newDemocracy Foundation, DemocracyCo and Mosaic Lab, and it is undeniable that some great work is going on in Australia in this area.

But alas, the path of democracy never did run smoothly. Suffice to say that cracks begin to emerge when you are outside the room. If decisions are legitimate to the extent that they have been deliberated upon, then the decisions made by a mini-public suffer a legitimacy deficit, given the typically small group involved (Parkinson 2003). And although some recent Citizens’ Juries have sought to expand the number of participants, this diminishes the quality of dialogue (Chambers 2009). Furthermore, in the past 15 years a growing number of scholars have sought to move beyond the mini-public paradigm in deliberative democracy to tackle deliberation at the large scale – through deliberative systems (Dryzek 2009; Parkinson and Mansbridge 2012), deliberative cultures (Sass and Dryzek 2013) and deliberative societies.

Yet, the practice of deliberative democracy (in Australia at least) clings to the mini-public approach. South Australia is notable for its extensive citizen engagement yes, but is it really innovative? The Western Australian Department of Planning and Infrastructure undertook a similarly ambitious program of mini-public style engagements over a decade ago. This critique is not a reflection on the quality of democratic practice in Australia, nor is it a criticism of what goes on inside the room. It is instead a concern that further underpins the need for deliberative theorists and practitioners to work together.

Outside the room: the populist challenge

Remember those NIMBYs and SIFs that mini-publics aim to exclude through random selection? Their exclusion rests on the assumption that the quality and outcome of deliberation is better without those insistent voices. The aim is that through a process of deliberation, people will become ‘more public-spirited, more tolerant, more knowledgeable, more attentive to the interests of others, and more probing of their own interests’ (Warren 1992, p8). Producing deliberated public opinion involves weeding out weak and poorly informed arguments. Again, this is all very well if you are inside the room. If you’re outside the room, you may very well object.

And let’s face it, those objectionable voices are not going away. As Ben Moffit points out, ‘Populism, once seen as a fringe phenomenon relegated to another era or only certain parts of the world, is now a mainstay of contemporary politics across the globe’. The voices that a Citizens’ Jury wants to keep out of the room now have the room surrounded. If we continue down the mini-publics road, the very thing that allegedly legitimises mini-publics will also be its downfall. The assumptions underpinning random selection are that it is representative of the wider community; and that it facilitates better quality deliberation by bringing together everyday citizens rather than insistent voices. Whether these things are accurate or not is a moot point – what actually matters is how they are perceived by broader publics. It is sad but possibly true that for those outside the room, what goes on inside the room doesn’t matter. And I suspect that the argument that a Jury is representative and very well informed is simply not going to cut it.

Trust in the Australian political system is at a staggering low with very little trust in any level of government; mini-publics in Australia are almost invariably associated with a government body or statutory authority. Mini-publics rely on information presented by experts; populism rejects the knowledge of experts. With all the will and most independently-recruited-and-facilitated process in the world – people may just not trust it. And yet, even if there were greater trust in politics, the justification of random selection explicitly rejects populist public opinion – and vice versa. Bridie Jabour’s Guardian interviews with One Nation voters exemplifies this disconnect. One Hanson supporter is quoted as saying:

“I’m not a politician, I’m not an accountant, I’m not anybody who knows anything but I see stuff and think ‘that doesn’t look right to me’, the average Joe Blow feels things more than they actually understand or know, they feel things, they know stuff.”

The logic of randomly selected mini-publics goes against this. The question is how to respond; the populist challenge cannot simply be ignored or sneered at. Yet in a way, this is exactly what mini-publics can be perceived as doing.

The time is right

We are at a critical juncture in Australia. One option is to continue plying the mini-public trade and make extra efforts to engage more people in the process, and to better explain mini-publics to a wider audience. The question is whether we simply need to work on explaining ourselves better, or whether the populist challenge requires deeper reflection on the practice of democratic innovation and deliberative democracy. I am inclined toward the latter.

The challenge that populism poses should be seized as a catalyst to re-think the practice of deliberative democracy in Australia. Mini-publics are one of many worthy options; deliberative democracy is a far broader church – and democratic innovation even more so. Randomly selected mini-publics are not a cure-all. At best, they are an important piece embedded in a broader democratic process. At worst, they are a viable threat to the practice of deliberative democracy itself.

You can find the posting of this article on the Participedia blog at www.participedia.net/en/news/2016/11/13/when-democratic-innovation-not-democratic-innovation-populist-challenge-australia.

Understanding Immigration

Social Movements and Leadership

In his autobiography, appropriately titled The Long Haul, activist and educator Myles Horton writes about the leadership of social movements. While great charismatic leaders serve an important galvanizing role and go down in history as the leader of the movement, the real power of a social moment is that it multiplies leadership – it turns the people themselves into leaders.

He tells the story of a elderly black woman who started a Citizen School. She heard the idea somewhere, figured it out, and taught a few other people how to do it as well. She had no idea Citizen Schools were happening all over. It was simply an idea which she could pick up and make her own. Horton writes:

It’s only in a movement that an idea is often made simple enough and direct enough that I can spread rapidly. Then your leadership multiplies very rapidly, because there’s something explosive going on. Please see that other people not so different from themselves do things that they thought could never be done. They’re emboldened and challenged by that step into the water, and once the get in the water, it’s as if they’ve never not been there.

assessing the charge of respectability politics

“Respectability politics” is a valuable term of criticism. Apparently, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham coined it in 1993. It refers to a strategy of trying to look “better” in the eyes of the dominant group in order to be accepted and make progress. Since respectability politics puts unjust and impossible burdens on the marginalized, we should diagnose and try to avoid it.

At the same time, successful social movements do try to look better. An appearance of moral or spiritual discipline and excellence–“Worthiness” –is an asset that social movements can build and use for political purposes, along with “Unity,” “Numbers,” and “Commitment” (WUNC, for short). They claim higher ground because that’s a powerful strategy.

Also, democratic social movements demand that their own members–previously excluded from civic life–be treated as full citizens. True citizens display values and commitments that are not very common in any population: for example, they are actively engaged with public issues and concerned for the common good. Therefore, in asserting a right to be full citizens, social movements often try to embody values that are better than what they see around them; they try to “Be the change.”

My friend Harry Boyte has saved the Program Notes from the 1963 March on Washington, which says, among other things: “In a neighborhood dispute there may be stunts, rough words, and even hot insults. But when a whole people speaks to its government, the dialogue and the action must be on a level reflecting the worth of that people and the responsibility of that government.”

I don’t think that message should be labeled “respectability politics.” The point of the Program Notes was not to look better to White people. The point was to live up to high expectations chosen and embraced by the Black leaders of the March. The movement redefined respectability–indeed, excellence–on its own terms.

For example, it’s traditional for a crowd at a march or rally to hear a famous and excellent singer. That is one way to display both worthiness and unity. At the 1963 March, Mahalia Jackson filled this traditional role when she sang, “I’ve Been ‘Buked, and I’ve Been Scorned.” The difference was that she sang an old gospel song about her own people. This was a performance designed to move and inspire Whites (and others) as well as African Americans, yet she didn’t sing a “White” song to obtain their support.

Likewise, Dr. King’s speech was aimed at a majority-White and overwhelmingly Christian nation, but his specific style of prophetic oratory was uniquely African American. One of the achievements of an effective social movement is an expansion or redefinition of respectability–but not an abandonment of respectability as an ideal.

It’s hard to redefine and consistently demonstrate respectability within a mass movement that is voluntary and democratic. People will join with all kinds of agendas and styles, and they have a right to that diversity. Some will make choices that look bad to others. Enemies of the movement will emphasize the outliers: for example, FoxNews showed footage of last Friday’s anarchists to illustrate Saturday’s vast and peaceful women’s marches. Still, I think the women’s marches represented “worthiness” to an extraordinary degree, and that is a basis for optimism about the next few years.

Opinions about any specific case will differ, but we can look at a sign, slogan, or statement; at a whole episode, like Saturday’s marches; or at a movement composed of many such episodes, and assign it to a category:

- Problematic respectability politics, when the movement adopts norms that exclude some people in order to gain support.

- Neutral respectability, when the movement just happens to be respectable in many people’s eyes, without adjusting its rhetoric or strategies or excluding anyone.

- Pursuit of excellence: whether by displaying self-sacrifice or by singing as well as Mahalia Jackson (or in many other ways), a movement presents itself as more than respectable. Most people cannot meet this ideal, but it becomes a resource for the whole movement. Maybe only Gandhi is starving himself, but we are all satyagrahis if we support him.

- Shifting the border of respectability in productive ways. For example, wearing a pink pussy hat on Saturday was a way of rebuking the utterly disreputable new president with a sly and kid-friendly answer. In my view, the hats were fully respectable, but in a way that shifted respectability slightly.

- Unhelpfully un-respectable politics, such as the anarchists’ window-breaking on Friday or (arguably) Madonna’s speech at the March.

My main point is that the choices are not just 1 or 5. Some movements fill the other categories, and all are options.

Trump, Trust, and Civic Renewal

- Citizens must trust their government if they are to invest it with responsibility.

- Trust between citizens is a good measure of civic capacity.

- Trust in institutions is a requirement for collaboration.

After the last few days, it seems obvious that we are headed for an alternative set of arrangements where a less trusting press and a less trusted Executive Branch part ways. I have a hard time seeing the upside of this divorce for progressive goals: since government needs trust to accomplish a lot of its goals, citizens with good reason to mistrust their government are very likely to respond by handing that government less responsibility. That will frustrate populists but not laissez-faire elites. Thus, less trust seems to be likely to increase the uptake of libertarian and neo-liberal ideas.

In some ways that’s the best case scenario: incompetence also lends itself to side deals and rent-seeking. We can end up with the minimal state via incompetence quite easily, but we could also keep the larger state but replace its technocratic reasons with pure regulatory capture and clientism. Think Tammany Hall or Mexico’s Partido Revolucionario Institucional.

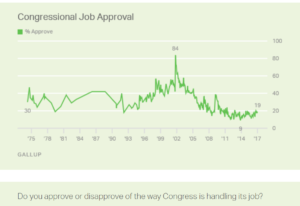

Yet mistrust did not begin recently. Except for a brief moment of post-9/11 patriotism, the US Congress has rarely been very popular in the modern era. Meanwhile, other indicators of mutual trust among citizens that have recently been quite low are on the rise, like those charted by Robert Putnam and the National Conference on Citizenship, which found in 2010 that in 2008 and 2009 only 46% of Americans talk with their neighbors and only 35% of Americans participate in community groups and organizations. Yet that number is on the rise: a follow-up study for the year 2011 found that 65.1% of Americans did favors or helped out their neighbors, and 44.1% of Americans were active in civic, religious, or school groups.

Yet mistrust did not begin recently. Except for a brief moment of post-9/11 patriotism, the US Congress has rarely been very popular in the modern era. Meanwhile, other indicators of mutual trust among citizens that have recently been quite low are on the rise, like those charted by Robert Putnam and the National Conference on Citizenship, which found in 2010 that in 2008 and 2009 only 46% of Americans talk with their neighbors and only 35% of Americans participate in community groups and organizations. Yet that number is on the rise: a follow-up study for the year 2011 found that 65.1% of Americans did favors or helped out their neighbors, and 44.1% of Americans were active in civic, religious, or school groups.

I would be remiss if I did not point out at that the Women’s Marches on Washington and elsewhere in the US brought out more than 1% of Americans. That’s a mass movement by any standard, to have so many women and men marching on a single day. Every indication is that this was the largest organized protest in the history of the US. Organizing and expanding that group is a major task, but it is one that will both require and create trust.

All of this suggests a rebalancing of trust and energy that is not so much progressive as local and civic. What we’re seeing today is a loss of trust in traditionally trustworthy institutions. Yet I wonder whether this mistrust may have something like a pneumatic quality, where losses of trust in one place are matched by increases elsewhere. It’s possible in the worst regimes to destroy trust everywhere–this is one way that totalitarian regimes operate–but there may be some net-positive transfers at the margin in our as-yet democratic society.

This move to the local is sometimes equated with conservative ideology, because of the long-standing equation of states rights arguments with conservatism. But localism can work to the advantage of progressive cities, too, if the same principles are applied equitably. (They may not be.) More than anything else, the current political climate shifts the kinds of solutions for which our fellow citizens will reach. Rather than hoping to make change at the national level, we must organize our political lives around more local efforts. Rather than seeking assistance from state institutions we must organize and act ourselves.

I have seen four specific projects suggested that I’d like to endorse:

- Replacing defunded programs: we should commit to privately fund programs cut by the Trump administration using any tax cuts that result. That means that if he follows through on the plan to cut school lunches or the National Endowment for the Arts, we should commit to meet the need. It will be much harder to replace Planned Parenthood, however, without state legislatures that can commit to meet any federal shortfalls.

- Replace lost federal regulations: The biggest cities rival many small countries as sources of carbon emissions and and as sites of action to slow climate change, so if the EPA cannot act, those cities must overcome free-rider problems to act on their own. If crucial aspects of the Affordable Care Act are eliminated, we should organize within our states and municipalities to replace them. If immigrants and refugees are threatened, we must protect them and act privately. The same goes for LGB (and especially T!) rights.

- Rejoin forgotten civic associations: I’m not a Christian, but atheism tends towards civic isolation. That’s why the first thing I did after the election was go to a Quaker Meeting. I also subscribed the New York Times after spending the last five years avoiding its paywall. And I’m signing up for Teen Vogue, too.

- Reinvigorate local party politics for both parties: Very few people participate in party politics. Very few people vote in primaries and local elections. Very few people trust either political party. It’s time to fix that. Here’s how Keith Ellison, candidate for DNC chair, describes one fix:

The real idea is not the big events. The real idea is the canvassing, the door knocking, the calling. Then the other thing we do is we continually ask people to help us. We’re asking people, “There’s a vote coming up. What do you think? There’s a vote coming up. What’s your opinion? Sign up on this petition. Sign up on that petition.” People are constantly feeling like they’re partnering with me as the member of Congress from their district.

Both parties can gain strength by becoming more inclusive and engaged. And when they do that, they’ll both serve their constituents–us–better. I continue to believe that partisanship has reduced our efficacy as citizens. But as the Big Sort continues, parties may be the best remedy for the harm they have done.

When is Deliberation Democratic?

The 14-page article, When is Deliberation Democratic?, was written by David Moscrop and Mark Warren, and published in the Journal of Public Deliberation: Vol. 12: Iss. 2. In the article, the authors theorize on how deliberative democracy operates in relation to equality and equity. They lift up two features that are of particular importance to pre-deliberative democracy: popular participation and agenda-setting, that must be paid attention to by theorist and practitioners. Deliberative democratic processes shape and are shaped by these two features, popular participation- how people show up and express their voice, and agenda-setting- how concerns are shaped into issues. The authors offer suggestions on responding to the challenges of equality and equity to democratic deliberation.

Read an excerpt of the article below and find the PDF available for download on the Journal of Public Deliberation site here.

From the article…

“Deliberative democracy” is a compound term. In both theory and practice, it connects deliberative influence through reason-giving, reciprocity, and publicity to a family of political systems that broadly enable popular control of the state and government through empowerments such as voting, petitioning, and contesting, as well as the electoral and judicial systems that enable them. These empowerments are democratic when they are distributed to, and usable by, those affected by collective decisions in ways that are both equal and equitable.

While deliberative influence is best protected and incentivized by democratic political systems, not all deliberation is democratic, and not all approaches to democracy are deliberative. We should distinguish and relate these terms: we need to differentiate the practice of deliberation from the contexts of democratic enablements and empowerments in which it occurs. We can then focus on the pre-deliberative conditions that will enable or limit the extent to which deliberation is democratic. Two pre-deliberative democratic features stand out as particularly important in this context: popular participation—how individuals come to have standing and voice as participants, and agenda setting—how concerns come to be defined as issues. We further argue that since deliberation typically occurs downstream from agenda-setting, and since popular participation both shapes and is shaped by this practice, theorists and practitioners of deliberative democracy should pay close attention to each feature well before deliberation begins.

To make this case, we first theorize the democratic dimensions of deliberative democracy through the concepts of equity and equality. Second, we focus on agenda-setting and popular participation as important, though not exclusive, pre-deliberative determinants of equality and equity during deliberation. Finally, we offer suggestions about how theorists and practitioners of deliberative democracy might think about responding to the challenges generated by the tension between equality and equity prior to democratic deliberation.

Equality, Equity, and Deliberative Democracy

Deliberation can be separated from democracy conceptually and practically. There can be deliberation that is not democratic and democratic practices that are not deliberative. For instance, Rawls (2001) considered the United States Supreme Court to be a pre-eminent deliberative body. But the Supreme Court has an agenda that is limited by judicial process and—though an important part of a democratic system—is remote from democratic control. There are also democratic practices that are not deliberative. These include practices such as aggregate voting and purely strategic uses of words and images in political campaigns.

At a high level of abstraction, we can conceive of the “democratic” part of deliberative democracy as comprised of equality in opportunities for participation, and equity in processes and outcomes. Within the context of democratic theory, equality almost always refers constitutionally to rights and empowerments that attach to citizenship—equal rights to vote, equal protections for speech and association, equal standing before the law, and equal supports for social precursors of participation, such as education. These equal rights and empowerments are justified by moral equality; each person is morally worthy and possessed of equal moral dignity, and assumed to be capable of self-government (Dahl, 1999). In a democracy, these rights, empowerments, and moral assumptions attach to each individual equally, simply by virtue of their citizenship. They do so regardless of actual social and economic inequalities, or inequalities of capacity. They belong to individuals whether or not they are able to make use of them. Finally, these kinds of rights and empowerments are relative to the political units through which they are organized; their effectiveness is conditioned by the control governments exercise over an issue, and by the ways political systems enable citizens to participate in the kinds of control a government might exercise, including (for example) electoral system design.

Equity is a different matter. While equality operates through distributions of rights and empowerments that attach to citizenship, equity requires that each person is given his or her due according to circumstance. Equity considerations draw attention to the highly variable ways in which individuals are situated within social relationships, and to the duties and obligations that individuals have to one another as co-dependents within collectivities. That is, equity reflects considerations of social justice (Pettit, 2012; Rawls, 2001). Thus, while equality may be said to operate on a simple principle—equal provision of formal empowerments and protections—equity is more demanding and less amenable to formalization, as it requires attentiveness to the circumstances of each individual. Ideally, equality enables equity: equal distribution of empowerments such as votes, rights, and opportunities for voice should enable citizens to press for equity, to place equity claims on the agenda, and to deliberate about what equity requires in the many different kinds of locations that comprise collectivities of interdependent equals. Equality, properly understood, ought to move a society toward equity: when equal empowerments underwrite voice, then deliberative mechanisms should enable finer-grained attentiveness to historical injustices, persistent prejudices, and highly variable starting places in life. But because these kinds of circumstances affect the ways in which citizens are able to use their equalities, questions of equity may also be pre-deliberative; precisely those who are relatively disadvantaged may need additional support, organization, or representation in order to have their voices included in deliberative processes.

Who Gets to Deliberate and about What?

When we convert these ideals into more substantive questions of deliberative democracy, two questions stand out: How are issues placed on deliberative agendas? And who gets to deliberate?

Download the full article from the Journal of Public Deliberation here.

About the Journal of Public Deliberation

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen friendly form.

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen friendly form.

Follow the Deliberative Democracy Consortium on Twitter: @delibdem

Follow the International Association of Public Participation [US] on Twitter: @IAP2USA

Resource Link: www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol12/iss2/art4/