Old Ohio Penitentiary by J. Harris Day

This semester I taught a course on crime and punishment, and in part out of competition with my colleague Seth Vannatta, I set out to give a final presentation on the dimensions of the course. This is the presentation I wrote.

Introduction

Our task was to explore the role of ethics in the law, and we began our semester worrying about standard ethical questions of responsibility and who to blame when things go wrong. The standard theories of punishment all revolve around these questions: whether we are utilitarians or contractarians, we are implicitly depending upon an account of what we owe to the criminal and to society. What’s more, the same assumptions underwrite our theories of what it is to deserve a grade (an A, an F), to deserve the love of our partners, or to deserve a particular job or a raise. This question of where to locate merit in our account of responsibility is particularly troubling, however, when someone is harmed, when a law is broken, or a right is infringed.

Simple questions of positive and common law or negligence, willfulness, and standards of care quickly morphed into a thorny metaphysical question: how can we be responsible for our acts if we could not have done otherwise, that is, if the mechanistic picture of the universe and our genetics and our society and our brains is true, and what I ate for breakfast or the crimes I commit before dinner are all predetermined?

Reactive Attitudes

The courts want to avoid such questions, but throughout the semester my contention was that they end up smuggling metaphysical accounts of agency into their descriptions of the non-culpability of children for trespass. Yet what we saw in Peter Stawson’s account of the reactive attitudes was an attempt to save responsibility, praise, and blame while jettisoning the supposedly-unavoidable metaphysical underpinnings. By redescribing blame and responsibility in terms of their own possibly-deterministic framework, Strawson allows us to say something like the following: “Maybe you could not have done other than what you have done, maybe your virtues and your vices are both unavoidable, but my reactions are no more avoidable. If you cannot be expected to have prevented your crimes, then I cannot be expected to prevent your punishment.”

This certainly appears to be a satisfying solution to the problem, because the law cannot requires a victim or a judge to achieve an inhuman level of restraint in the face of a dazzling failure of restraint in the perpetrator. Strawson’s “reactive attitudes” account comforts us by communicating just how unfair this asymmetry actually is. And yet… in beginning to spell out conditions for the defeasibility for responsibility, Strawson reiterates that not all actions and reactions are symmetrical. Under many circumstances, a victim truly does have more restraint than a perpetrator, and ought to exercise it, too. (Not just to prevent cycles of reprisal, although that certainly counts in its favor; to get beyond a mere modus vivendi to what we might mean by justice.) Even more: a judge’s capacity to see beyond the dyadic relationship of injury and blame means that she can ask questions about the overarching justice and efficacy of a punishment.

Grammatical Theories

Thus we entered what we called the “grammatical” theories of agency and responsibility. We experience our own lives through the first-person lens, as “I.” Meanwhile, we can talk about the other person in two different ways: as a second-person “you” or as a third-person “them.” And underwriting these lenses or grammatical conventions is the fact that we tend to see ourselves as agents and others as passive, to an extent that is so asymmetric and inconsistent that it is hard to believe it can be warranted. For instance, we are much more likely to explain our own failings in terms of circumstances, while we tend to describe the failings of others in terms of character, intention, or predilection. “I” fail because of events and impediments beyond my control, despite my best efforts. “You” fail because you didn’t try hard enough, you just weren’t willing to work at it; “they” fail because that’s just what they’re like, “they” are failures.

So what starts as an attempt to avoid the difficult metaphysical problems gets bogged down in our cognitive heuristics and biases. In gathering the texts we read together, I tried to duck this problem by adopting the third-person perspective, moving the course from the questions of just deserts to systematic accounts of the problem. Of course, all the intutions and issues of first-person and second-person agency and responsibility are still lurking there for you to pick up, if you like, but we’re all fascinated by the political theory and history, so I followed our collective inclinations. “Don’t blame me!” I guess I’m saying. “We are collectively responsible!”

The Republican Theory of Punishment

In order to ground our discussions of justice, we tried to transition from metaphysical and psychological accounts of freedom to the political and legal theory of liberty, that thing of which coercion and the threat of interference and violence deprives us. At about this point it began to be increasingly difficult to ignore issues of race, even in the sense of putting them off until we got to Michele Alexander’s book. So when John Braithwaite and Philip Pettit offered a theory of dominion as the equality of social status and defended it explicitly with reference to the differential “costs of victimization investigation” that African-Americans face, it became increasingly difficult to ignore the discriminatory intents and impacts of things like the death penalty.

Perhaps the most interesting insight that Braithwaite and Pettit offer is the conclusion that much punishment is simply an attempt to preserve hierarchy rather than to right an inequality. This is something we well-recognize in looking around at the race and class of those who get punished in the US, but philosophers too frequently ignore it. What’s more Braithwaite and Pettit offered us an explanation of what makes coercion and domination so difficult: not the harm or loss of utility, nor the shear loss of doing what you want to do, but the way that it harms our social standing, makes some “better than” and others “less than.” Many political philosophers have concluded that a democratic society cannot function if it is not populated by social equals. The only problem is that so many so-called democracies *do* seem to have serious social hierarchies, and as university students and faculty we inhabit an elitist institution that sets out to distinguish erudition from ignorance and good work from bad.

Costs and Benefits

One way to articulate the appeal of the theory of non-domination that Pettit offered is the way in which it gives us a tool to balance the costs of victimization against the costs of investigation and incarceration. But the balancing act favored just one variable, equality, and it seemed that this is not the only way to proceed. Sometimes, as in markets, equality should take a back-seat to other values, like efficiency and optimality.

In his book When Brute Force Fails, Mark Kleiman offered a different account. He suggested that given how much we spend on and lose to crime-avoidance, perhaps some large amount of criminality is simply inefficient, and we’d be better off spending even more of our scarce resources on eliminating it. What is more, he suggested, we not only need to spend more preventing crime, but we need to spend these greater resources more intelligently. (Work harder AND smarter.) Yet the real strength of his argument is not so much the cost-benefit analysis but his prescriptions: that infrequent, uncertain, and severe punishments are simply not much of a deterrent, while swift, certain, and light-but-escalating punishments could be much more effective, saving us costs to the criminal as well as the victim.

Given how much crime costs us as a society (and Kleiman includes the cost to the criminals!) there is much benefit to be had from preventing it. Yet so long as we organize our response to crime around the concept of punishment rather than prevention, we will tend to choose more severe and less effective regimes of investigation, correction, and incarceration.

Surveillance and Punishment

Despite its appeal, Kleiman’s prescriptions fall under the rubric of an increasingly surveyed disciplinary society, one that simply uses new technologies from psychology and economics to do a better job of controlling its citizenry. The justification for this increased control is that citizens desire safety and security more than they wish to be free from such disciplinary technologies, and Kleiman is undoubtedly right that that is our preference. However, we should worry.

The heart of the course was a close reading of Foucault’s book Discipline and Punish, and if his history taught us anything, it is that social knowledge always has two faces: the production of justificatory knowledge and “truths” by experts who stand to gain from their expertise, and the development of practices and techniques for the regulation and management of bodies.

Much of the first half of the semester was devoted to the production of knowledge and the progress we have made in discerning the true and the just ways of investigating and punishing. But what Foucault attempts to lay bare is the way in which our contemporary treatments of prisoners’ bodies are only intensifications of historical brutalities we think of as inhumane. The intensification follows an introverting path: we have certainly lost the stomach for the spectacle of the regicide being drawn and quartered or the criminal hung on the scaffold. But incarceration and rehabilitation, the watch-words of criminal science, take up a set of tasks related to the ordering of unruly and delinquent bodies that is much more effective but no less self-serving. We now have the tools for more power, and if Foucault is right then we will generally put these instruments to use in asserting our own advantage by dominating others.

Both the concerns about social hierarchies and the recognition of the radically racialized form that incarceration and punishment take in the US suggest that “our own advantage” may include my students and I, but it is unlikely to include the majority of black people and it is unlikely to include the majority of people without college degrees. Recognizing the power that our knowledge allows us does not mean that we can necessarily bend that power to our wills; it is much more likely that it will continue to accrue advantages for us even if we try to betray it, just a rich person’s Capital continues to make money even if they purport to be egalitarian communists.

Punitive Isolation and Bare Life

Deepening our understanding of the techniques of imprisonment, we read essays (including a great one by Lisa Guenther) on the horrors of solitary confinement and the sometimes bewildering Homo Sacre by Giorgio Agamben on the forms of exclusion that seem to have a permanent place in our prison system.

If Agamben is right, then these new forms are all a part of an overarching paradigm, that of the reduction of human beings to their mere physicality and biology. This political movement towards reduction transforms flourishing into survival, and it does it in a way that has been continuously experimented with since the first colonists started to round South African natives into “concentration camps” for ease of management. When those colonial overlords returned home to Europe, they brought their techniques of domination with them, and so in that sense the Holocaust was Europe’s chickens coming home to roost, a “boomerang effect” by which European Jews reap what European capitalists sow.

Biopolitics is a form of legal sovereignty in which “modern man” is a depicted as “an animal whose politics calls his existence as a living being into question” but it makes sense only as a development of the totalitarian interpenetration of politics and private life. The modern sovereign no longer decides between ‘letting his subjects live or making them die,’ rather he chooses to ‘make them live or let them die.’ Thus he distinguishes the form of a power that disciplines its subjects and channels their activity from one that simply responds to infractions with infrequent but grotesque punishments.

Trying to spell out exactly how these new techniques and knowledges serve the purpose of domination is something of a challenge precisely because they are still in the experimental stage, still being contested. In the absence of opposition, however, they have been allowed to remain in unquestioned use for far too long. The very nature of bare life and isolation means that the contestation that would normally be working through these techniques and forcing them to receive some form of justification has been slow to form even among those academics who are supposedly most opposed to domination and who purport to ally themselves always and everywhere with the downtrodden and silenced. Let me suggest one reason, at least, why you should think that there is still work to do.

Agamben suggests that we ought to see ourselves in solidarity with the least of us; the immigrants and refugees, those without rights. No doubt he is motivated by the idea that the rightless are marked by the fact that they rise in status when they have committed a crime, because only then are they granted procedural rights (like the right to a trial) and recognized within the legal framework. In practice, however, it may be more effective to view prisoners through the lens of the nomos of the camp.

The New Jim Crow

One concept we did not discuss in our class in much detail is race solidarity and race treason. But when we turned to Michelle Alexander’s book it became obvious just how difficult such a discussion might be. Having made a persuasive case for the differential intention and impact of the current system of mass incarceration, Alexander then asks her readers, who she assumes will be bourgeois African-Americans like my students, to engage in a radical act of political solidarity. Rather than putting our hope in a Black president, Alexander suggests that quietly celebrating civil rights victories from fifty years ago while enjoying the benefits of what she calls the “Racial Bribe” is a kind of racial treason: selling out the majority of African-Americans for the spoils of white supremacy by becoming complicit in it. In contrast, she suggests that true opposition to white supremacy will require a rejection of the racial bribe and a laser-focus on the policies currently at work in the domination of African-Americans.

We started this class asking what sort of punishment we owe to the criminal: at the conclusion, Alexander proposed that what we owe to the criminal is solidarity. I suspect that this is a difficult proposal to accept. I do not know how to make the case any stronger than she made it, so I will simply quote Baldwin, as she does:

these men are your brothers—your lost, younger brothers. And if the word integration means anything, this is what it means: that we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it. For this is your home, my friend, do not be driven from it; great men have done great things here, and will again, and we can make America what it must become. It will be hard, but you come from sturdy, peasant stock, men who picked cotton and dammed rivers and built railroads, and, in the teeth of the most terrifying odds, achieved an unassailable and monumental dignity. You come from a long line of great poets since Homer. One of them said, The very time I thought I was lost, My dungeon shook and my chains fell off…. We cannot be free until they are free.

Yet as a white professor of African-American students, I cannot quite countenance her proposals, like when she took to the pages of the New York Times calling for a plea-bargain strike, suggesting that everyone accused of a crime act in solidarity to force the courts to a halt: “Go to Trial: Crash the Justice System.”

“What would happen if we organized thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of people charged with crimes to refuse to play the game, to refuse to plea out? What if they all insisted on their Sixth Amendment right to trial? Couldn’t we bring the whole system to a halt just like that?”

I tend to think this kind of collective action is unworkable, in part because it puts the responsibility to act on people who are risking very serious jail time if they proceed.

However, the key focus of this proposal is not only to increase demand for lawyers and judges beyond the point the system can handle, but also to increase the demand for jurors so that we must actually face what we have collectively done. Right now almost no criminal can afford to take advantage of his supposed constitutional right to a jury trial. We do everything in our power to coerce them not to use that right, and the results are spectacularly unjust even if every one of them is guilty. As a result, most citizens don’t have to face up to the decision-making a jury trail entails. That’s part of why mass incarceration is of so little interest to most people: out of sight, out of mind. At least a plea-bargain strike would put citizens back in the drivers’ seat. When we get tired enough of jury duty, perhaps we will vote to decriminalize some of the things that are taking us away from our work and families. But so long as we can leave the job to prosecutors, we’ll likely continue to vote for tougher laws and more “tools in the arsenal of prosecutors,” which is an arms race prosecutors have long since won.

Throughout the course we saw a very diverse set of authors arguing that something akin to an abolution of incarceration was required. I didn’t always realize that a text could be read in that way, but it was a running theme. It’s almost impossible to imagine, now; yet I think that these unimaginable things are often what most needs philosophical work. Why not imagine a world where almost 2% of our fellow citizens are in some way dominated by the criminal justice system? Why not imagine a world where we regularly isolate prisoners, depriving wrongdoers of the social bonds that would be required to reenter society?

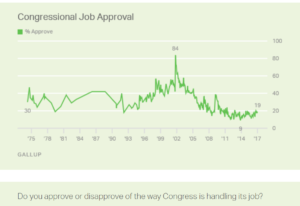

Yet mistrust did not begin recently. Except for a brief moment of post-9/11 patriotism, the US Congress has rarely been very popular in the modern era. Meanwhile, other indicators of mutual trust among citizens that have recently been quite low are on the rise, like those charted by Robert Putnam and the National Conference on Citizenship, which found in 2010 that in 2008 and 2009 only 46% of Americans talk with their neighbors and only 35% of Americans participate in community groups and organizations. Yet that number is on the rise: a follow-up study for the year 2011 found that 65.1% of Americans did favors or helped out their neighbors, and 44.1% of Americans were active in civic, religious, or school groups.

Yet mistrust did not begin recently. Except for a brief moment of post-9/11 patriotism, the US Congress has rarely been very popular in the modern era. Meanwhile, other indicators of mutual trust among citizens that have recently been quite low are on the rise, like those charted by Robert Putnam and the National Conference on Citizenship, which found in 2010 that in 2008 and 2009 only 46% of Americans talk with their neighbors and only 35% of Americans participate in community groups and organizations. Yet that number is on the rise: a follow-up study for the year 2011 found that 65.1% of Americans did favors or helped out their neighbors, and 44.1% of Americans were active in civic, religious, or school groups.