Monthly Archives: December 2016

Epson printer customer care number UK

Most Popular Posts from 2016

“That man who has nothing to lose:” Black Americans and Superfluousness

Long before white Americans felt like their society had abandoned them, Black Americans knew the feeling. Just like whites do today, some Black Americans responded to earlier superfluousness by “clinging to guns and religion” to use Barack Obama’s famous analysis. (cf. Kinsley gaffe) Here’s James Baldwin, describing the Nation of Islam:

“I’ve come,” said Elijah, “to give you something which can never be taken away from you.” How solemn the table became then, and how great a light rose in the dark faces! This is the message that has spread through streets and tenements and prisons, through the narcotics wards, and past the filth and sadism of mental hospitals to a people from whom everything has been taken away, including, most crucially, their sense of their own worth. People cannot live without this sense; they will do anything whatever to regain it. This is why the most dangerous creation of any society is that man who has nothing to lose. You do not need ten such men—one will do. And Elijah, I should imagine, has had nothing to lose since the day he saw his father’s blood rush out—rush down, and splash, so the legend has it, down through the leaves of a tree, on him. But neither did the other men around the table have anything to lose. –James Baldwin, “Down At The Cross: Letter from a Region in my Mind“

Baldwin was no fan of Elijah Muhammed’s movement, but he tries to understand it and he seems to sympathize. And what he calls out in these lines is an overriding sense of loss–one that can justify any effort or sacrifice to overcome. That loss of worth, which Baldwin wants to depict as something much deeper than “self-esteem,” is tied not to airy questions of recognition but to material harms and embodied injuries: frisks and kicks by “legitimate” authority that go unanswered, murdered fathers that go unmourned by white society.

Baldwin even interprets the turn to Islam as a turn away from Christianity’s whiteness–from the forgiveness that it seems constantly to demand from white supremacy’s victims.

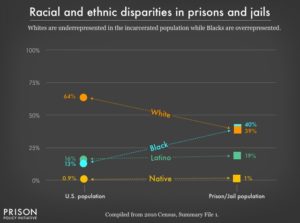

Today I know more Black Muslims than Arab ones, but mostly they’re imprisoned. And that, too, is a form of superfluousness: of the 2.3 million people incarcerated in the US, 40% are Black, even though Blacks make up only 13% of the population.

It’s hard not to see imprisonment of African-Americans as primarily a reaction to their enforced superfluousness. Labor market prejudices create a circumstance where unemployment rates for African-Americans are roughly double the rates for whites, at every education level. My students believe (and I agree) that the War on Drugs is largely a war on Black participation in the black labor market. (Recall the Ice Cream truck war of the summer which helps explain how police and the courts can make black markets less or more violent.) It’s an attempt to foreclose available forums for Black entrepreneurship. It’s notable that as marijuana legalization proceeds state-by-state it begins in white places, and the new profits and businesses are primarily white-owned.

To be rendered superfluous is a particularly odd phenomenon, and at least in the formulation I’ve lately been thinking about, it seems uniquely tied to relative deprivations of status and respect. I want to believe that respect and recognition matter less than life or health. We all have things we could lose, and honor is the least of these.

But that’s simply not how people act. Flourishing matters to most people more than survival, and flourishing requires a community of esteem. It requires reputation and character assessments, it requires that the agents of the state give you equal protection and don’t target you as a unique threat.

Some parts of Black America responded to superfluousness by clinging to god and guns, but for the most part African-Americans responded by becoming the center of cultural attention. There’s little argument that Black culture simply is American culture at this point, as almost all of our distinctively American institutions and cultural traditions are shot-through with Blackness even if it is unacknowledged. Baldwin charged that even myths of Black laziness or violence serve an important function in White America: they are our “fixed star” and moving out of their place of subordination would shake our “heaven and earth… to their foundations.”

Yet whites don’t seem to be willing to create their own economies of esteem in this way. Something–perhaps supremacy itself–has rendered them too lazy, too dependent on long-lost tradition and long-gone cultural victories. Consider Katherine Cramer’s formulation: rural Wisconsinites resent that the urban centers have deprived them of “power, money, and respect.” But they’re simply wrong: they’ve seen no real deprivations of power or money compared to Black Americans. It’s certainly true that they receive less respect than they used to get, less deference and less cultural attention. But this is a downfall from absolute supremacy and literal enslavement–enforced by rule of law. We have a long way to go before we aren’t still reaping what WEB Du Bois called “psychic wages” of white supremacy. (I prefer to call them psychic dividends, since it’s important that they are not a reward for work, but rather like a racial trust fund.)

How much should that matter? In my heart, I want to believe that people with a surplus of money, power, and respect should share. And I want to believe that it’s not a finite resource, that more souls can and will produce more of each if they’re not forced into superflousness. I think of Malcolm X, whose industriousness and self-invention could not be halted or stultified by racism or even Elijah Muhammed’s theocratic nonsense, only assassinated. But that’s where my analysis is probably wrong: when people have the money and power, they’re well-placed to demand the respect or punish its absence.

Robert Macfarlane: How Language Reconnects Us with Place

I have come to realize that language is an indispensable portal into the deeper mysteries of the commons. The words we use – to name aspects of nature, to evoke feelings associated with each other and shared wealth, to express ourselves in sly, subtle or playful ways – our words themselves are bridges to the natural world. They mysteriously makes it more real or at least more socially legible.

What a gift that British nature writer Robert Macfarlane has given us in his book Landmarks! The book is a series of essays about how words and literature help us to relate to our local landscapes and to the human condition. The book is also a glossary of scores of unusual words from various regions, occupations and poets, showing how language brings us into more intimate relations with nature. Macfarlane introduces us to entire collections of words for highly precise aspects of coastal land, mountain terrain, marshes, edgelands, water, “northlands,” and many other landscapes.

In the Shetlands, for example, skalva is a word for “clinging snow falling in large damp flakes.” In Dorset, an icicle is often called a clinkerbell. Hikers often call a jumble of boulders requiring careful negotiation a choke. In Yorkshire, a gaping fissure or abyss is called a jaw-hole. In Ireland, a party of men, usually neighboring farmers, helping each other out during harvests, is known as a boon. The poet Gerard Manley Hopkins called a profusion of hedge blossom in full spring a May-mess.

You get the idea. There are thousands of such terms in circulation in the world, each testifying to a special type of human attention and relationship to the land. There are words for types of moving water and rock ledges, words for certain tree branches and roots, words for wild game that hunters pursue. There are even specialized words for water that collects in one’s shoe – lodan, in Gaelic – and for a hill that terminates a range – strone, in Scotland.

Such vocabularies bring to life our relationship with the outside world. They point to its buzzing aliveness. There is a reason that government bureaucracies that “manage” land as "resources" don’t use these types of words. Their priority is an institutional mastery of nature, not a human conversation or connection with it.

Looking Back at NCDD 2016 and What Has Happened Since

The 2016 National Conference on Dialogue & Deliberation brought together 350 innovators in dialogue and deliberation to discuss the conference theme of Bridging Our Divides. Over the course of three days we discussed how to tackle some of today’s toughest divides, including partisan, racial, economic, and more. For a recap of the conference in numbers, see our earlier blog post.

The 2016 National Conference on Dialogue & Deliberation brought together 350 innovators in dialogue and deliberation to discuss the conference theme of Bridging Our Divides. Over the course of three days we discussed how to tackle some of today’s toughest divides, including partisan, racial, economic, and more. For a recap of the conference in numbers, see our earlier blog post.

Since the conference, NCDD has been producing and gathering media that captures our time together and the stories of our work. And, we’ve been following up on the conversations that happened at the conference and continuing the important work that began or was renewed in our time together.

Sharing the Stories of the Conference

At NCDD 2016 Keith Harrington of Shoestring Videos recorded our plenary sessions as well as short videos of participants. Keith is in the process of producing several videos, and has shared with us the following two videos:

Panel on Philanthropy and Fundraising

Mark Gerzon of the Mediators Foundation moderated a discussion among a panel of philanthropists about the constraints and opportunities facing our field’s efforts to bring people together across divides. Panelists shared their experiences funding bridge building efforts and answered participant questions about how we can all be better advocates for our work.

Panel on Journalism and Public Engagement

Peggy Holman of Journalism that Matters moderated a panel discussion among journalists, discussing both their work in engaging the public and discussing the opportunities they see for public engagement practitioners to partner with journalists.

Sharing More Personal Stories

Sharing More Personal Stories

In addition to video, for the first time ever at an NCDD conference we offered participants the chance to record stories and conversation in an audio room, run by sound designer Ryan Spenser. We recorded several conversations that would become our first episodes of our new NCDD Podcast. Check it out on iTunes, SoundCloud, and Google Play. Our first episodes are now live:

- Listen to Barbara Simonetti, NCDD’s Board Chair, and myself discuss her metaphor for the D&D field as a utility

- Hear the story of Conversation Café from co-creator Susan Partnow and past steward Jacquelyn Pogue, as they speak with NCDD Resource Curator Keiva Hummel about the process and their hopes for it under NCDD’s stewardship

Stories of bridging our divides were shared throughout the conference – in workshops, informal gatherings, and particularly in our first plenary session where we asked all participants to share a story of a time they witnessed divides being bridged.

We welcome additional stories of how you or those you are working with are bridging divides. In particular, we’d love to have people share using our Storytelling Tool. Using the tool gives NCDD the details for a great case story that we can share on our blog, so your story is shared with more people!

Last but not least, last week we shared our Storify page – take a look at that for a great recap of the social media activity during the conference, along with great photos and quotes!

Continuing this Work

Lots of inspiration was drawn from our time with you all at NCDD 2016, and we have been working to continue to address the needs and desires that arose at the conference. Some of the ways we’ll continue to do that include:

- The Race, Police and Reconciliation Discussion List: The racial divide was a central part of the conference theme. Many workshops addressed this divide and we heard from three panelists in our first plenary about their work in this area (video coming soon!). Many participants expressed a desire to connect with others on this work, and so NCDD has launched a discussion listserv for folks interested in connecting with one another. So far, more than one hundred of you have joined! Learn more here and then join the listserv.

- Our #BridgingOurDivides campaign: NCDD has continued our conversation at the conference over the past several months through our #BridgingOurDivides campaign. We’ve been sharing information and resources on social media and the blog. We also hosted a call for our community to talk about our post-election work. We’ll keep this conversation going in 2017, as this work is more important than ever.

The Emerging Leaders Initiative: NCDD has worked hard to bring students and youth to our conferences in 2014 and 2016, and in between we have been talking with these young and emerging leaders about how to get them involved in NCDD. This has all culminated in our new Emerging Leaders Initiative, which we’ll be more formally launching in 2017. We need to foster long-term resilience for the field of dialogue & deliberation, and we can do that best by intentionally cultivating our field’s next generation of leadership.

The Emerging Leaders Initiative: NCDD has worked hard to bring students and youth to our conferences in 2014 and 2016, and in between we have been talking with these young and emerging leaders about how to get them involved in NCDD. This has all culminated in our new Emerging Leaders Initiative, which we’ll be more formally launching in 2017. We need to foster long-term resilience for the field of dialogue & deliberation, and we can do that best by intentionally cultivating our field’s next generation of leadership.

We had such a great time at NCDD 2016 connecting and re-connecting with you all and discussing how we can continue to do this important work of bridging our divides in today’s world. Let’s use what has been generated from the conference and continue to build upon it – our communities and our country need dialogue and deliberation right now.

Vallejo: A model for broader engagement in participatory budgeting

winter break

As friends know, I’ve been blogging almost daily here since Jan. 8, 2003 (with 3,313 posts so far). I usually try to rotate among political analysis, social theory, and some cultural commentary. While I expected Clinton to win the 2016 election, I looked forward to reducing the frequency of my topical political posts. Barack Obama is a leader for whom I feel unique regard and emotional commitment. I thought that once his eight years were over, I’d try to go a bit deeper into theory, while the US political system entered a period of–as I expected then–stalemate. Instead, on Nov. 8, we experienced the civic nightmare of a Trump victory. For the first time in nearly 14 years of blogging, I have focused essentially on one question every day: how to respond? Although this remains a comparatively low-traffic site, it saw enormous growth compared to any time in its history. Particularly popular posts (by my standards) have been:

- how to respond?

- time for civil courage

- separating populism from anti-intellectualism

- why political science dismissed Trump and political theory predicted him, revisited

- should civic educators modify their neutral stance?

- pluralist populism

- to beat Trump, invest in organizing

We are about to take a family vacation, and I am also feeling the need for a mental break–not to retreat from political engagement (much as I would like to be able to consider that option), but to regroup and consider how to be most useful. Thus I am signing off until Jan. 2. Happy holidays!