Monthly Archives: March 2016

Only Authentic Community Engagement and Empowerment Can Begin to Restore Flint

A Brief History of Saint Days

So, I went down a bit of a rabbit hole this morning trying to figure out answers to what I thought were somewhat straightforward questions. First, when did people in various western European countries stop celebrating their Saints’ day – or name day, if you will – and second, how did the various reorganizations of the liturgical calendar affect name day celebrations?

I rather thought there would be plenty of information and resources to explore these questions, but I’m afraid I’ve merely found fragments.

The Catholic Church has celebrated feast days for important saints nearly since its inception. St. Martin of Tours, born in 316 in Sabaria (now Szombathely, Hungary) is thought to be the first saint – or at least the first to not die as a marytr.

Saint days quickly became a staple of the early Catholic church. As Christian Rohr has argued, these were not just days of religious observance, but were deeply seeped in the symbols and politics of their times:

When the feudal and the chivalrous system had been fully established during the High Middle Ages these leading social groups had to find an identity of their own by celebrating courtly feasts. So, they distinguished themselves from the rest of the people. Aristocratic festival culture, consisting of tournaments, courtly poetry and music, but also of expensive banquets, was shown openly to the public, representing the own personality or the own social group in general. Town citizens and craftsmen, however, were organized in brotherhoods and guilds; they demonstrated their community by celebrating common procession, such as on the commemoration day of the patron saint of their town or of their profession.

These courtly feasts were “held on high religious celebration days” – over half took place on Whitsunday. For craftsmen, Rohr points to the French city of Colmar, where “the bakers once stroke for more than ten years to receive the privilege to bear candles with them during the annual procession for the town patron.”

And, somewhere amid these deeply interwoven strands of religion, economics, and power, people began celebrating their own Saints’ day. That is, as most people shared a name with one of the saints, that saint’s feast day would have special significance for them.

It’s unclear to me exactly when or how this came about. Most references I read about these name day celebrations simply indicate that they have “long been popular.”

Name days celebrations today – though generally more secular in their modern incarnation – take place in a range of “Catholic and Orthodox countries…and [have] continued in some measure in countries, such the Scandinavian countries, whose Protestant established church retains certain Catholic traditions.”

But here’s the interesting thing: at least based on Wikipedia’s list of countries where name day celebrations are common, the practice is much more common in Eastern Orthodox countries than in Roman Catholic ones.

Now, the great East–West Schism – which officially divided the two churches – took place in 1054. My sense – though I’ve had trouble finding documentation of this – is that celebrating one’s saints’ day was a common practice in both east and west at that time. Name day celebrations do take place in the western European countries of France, Germany, and – importantly – Italy, which seems to indicate that the difference in name day celebration rates is not merely a reflection of an east-west divide.

It’s entirely unclear to me what led to this discrepancy. One theory is that this a by-product of the Reformation – during which time, at least in the UK, various laws banned Catholics from practicing.

But, I also find myself wondering about the effects of various reorganizations of the (Roman Catholic) liturgical calendar – eg, the calendar of Saint Days and other religious festivals. The calendar has been adjusted many times over the years, including as recently as 1969, when Pope Paul VI, explaining that “in the course of centuries the feasts of the saints have become more and more numerous,” wrote justified the new calendar:

…the names of some saints have been removed from the universal Calendar, and the faculty has been given of re-establishing in regions concerned, if it is desired, the commemorations and cult of other saints. The suppression of reference to a certain number of saints who are not universally known has permitted the insertion, within the Roman Calendar, of names of some martyrs of regions where the proclaiming of the Gospel arrived at a later date. Thus, as representatives of their countries, those who have won renown by the shedding of their blood for Christ or by their outstanding virtues enjoy the same dignity in this same catalogue.

Most notably and controversially, Saint Christopher was deemed to not be of the official Roman tradition, though celebration of his feast day is still permitted under some regional calendars. If you’re curious, you can read a list of the full changes made to liturgical calendar in 1969.

Many of these changes, such as the removal of Symphorosa and her seven sons, likely had little effect on anyone’s name day celebration. But, by mere probability, I would think that at some point over the years, someone had their Saint removed from the liturgy – which I imagine would probably be a rather disarming event. Though I suspect that wasn’t a big enough factor in diminishing the strength of the celebration over time.

Well, that is all that I have been able to find out. I have many unanswered questions and many more which keep popping up. If you have some expertise in Catholic liturgy and have any theories or answers, please let me know. Otherwise, I suppose, it will remain another historical mystery.

Innovations in Am. Government Award Accepting Applicants

We want to make sure that our members are aware of a great opportunity for recognition in public participation from Harvard’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation – one of our NCDD member organizations.

The Ash Center operates the Innovations in American Government (IAG) Awards Program and the Bright Ideas Initiative, both of which are aimed at recognizing creative and effective governance models and disseminating ideas about promising government practices or programs. We are positive that many of the programs and initiatives that our NCDD members work on every day would make great candidates for these honors, so we encourage you to nominate a program you know about or apply yourself!

The Ash Center operates the Innovations in American Government (IAG) Awards Program and the Bright Ideas Initiative, both of which are aimed at recognizing creative and effective governance models and disseminating ideas about promising government practices or programs. We are positive that many of the programs and initiatives that our NCDD members work on every day would make great candidates for these honors, so we encourage you to nominate a program you know about or apply yourself!

The winners of the IAG Award are eligible for a $100,000 grant, and even the finalists are eligible for a grant of $10,000, so what do you have to lose? The deadline to apply is April 15th, so make sure you get started soon!

Both of these prestigious awards have a long history of recognizing leading innovations in governance. Here’s how the Ash Center describes the Innovations in American Government Award:

Since its inception in 1985, Innovations in American Government Awards has identified and celebrated outstanding examples of creative problem solving at the state, city, town, county, tribal, and territorial government level. In 1995, the Innovations Awards were expanded to incorporate innovations in the federal government. The Awards program accepts applications in all policy areas; from training employees to juvenile justice, recycling to adult education, parks to the management of debt, public health to e-governance, Innovations applicants reflect the full scope of government activity.

And here is how they describe the Bright Ideas Initiative:

…[I]n 2010 the Innovations Program launched a recognition initiative called Bright Ideas that serves to further highlight and promote creative government initiatives and partnerships so that government leaders, public servants, and other individuals can learn about noteworthy ideas and can adopt those initiatives that can work in their own communities.

Beginning with these Bright Ideas, the Innovations Program seeks to create an open collection of innovations in order to create an online community where innovative ideas can be proposed, shared, and disseminated.

For more details on eligibility requirements, selection criteria, or to apply for these awards, visit https://innovationsaward.harvard.edu/IAGAwards.cfm.

Good luck to all the applicants!

To Address Gender Equity in the Workforce, We Must Look to Higher Education

The Easter Rebellion and Lessons From Our Past

I had planned today to write something commemorating the centenary of Ireland’s Easter Rising; the quickly-crushed insurrection which paved the way for the Irish Free State.

But such reflections seem somewhat callous against the grim backdrop of current world events.

Just this weekend, a suicide bomber killed at least 70 – mostly children – in an attack on a park in Lahore, Pakistan.

I debated this morning whether to write about that instead. Whether to grieve the mounting death toll from attacks around the world, or whether to question, again, our seemingly preferential concern for places like Brussels and Paris. Or perhaps to highlight the inequities evident in such headlines as CNN’s In Pakistan, Taliban’s Easter bombing targets, kills scores of Christians.

The majority of those killed were Muslim.

Perhaps these details hardly matter; it is all of it a horror.

But if I were to write about every global tragedy, these pages would find room for little else. There is no end to suffering, no limit of atrocity.

Perhaps I should write instead about Radovan Karadzic, the former Bosnian Serb leader, who – twenty years after orchestrating the ethnic cleansing of Srebrenica – was just convicted of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity by a United Nations tribunal.

Of course, such news also serves as a reminder that Omar al-Bashir, the current, sitting president of Sudan, is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes and crimes against humanity. He is also widely considered to be a perpetrator of genocide, though the ICC demurred from making that charge. The ICC issued its arrest warrant in 2009, citing numerous crimes committed since 2003. Bashir won reelection in 2010 and again in 2015.

It is all too much.

Perhaps I should write about the Easter Rising – a notable event for my own family – after all.

In the midsts of World War I, on Easter Monday 1916, 1,600 Irish rebels seized strategic government buildings across Dublin. From the city’s General Post Office, Patrick Pearse and other leading of the rising, issued a Proclamation of the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic:

We declare the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies, to be sovereign and indefeasible. The long usurpation of that right by a foreign people and government has not extinguished the right, nor can it ever be extinguished except by the destruction of the Irish people.

The overwhelming superiority of British artillery soon put an end to the provisional government. Over 500 people were killed; more than half were civilians. In The Rising historian Fearghal McGarry argues that Irish rebels attempted to avoid needless bloodshed, while, according to one British soldier, the British troops, “regarded, not unreasonably, everyone they saw as an enemy, and fired at anything that moved.”

During the fighting, the British artillery attacks were so intense that the General Post Office (GPO) was left as little but a burnt-out shell. As an aside, the GPO housed generations of census records and other government documents – making my mother’s efforts to recreate my family tree permanently impossible.

After the the rebellion had been crushed, fifteen people identified as leaders were executed by firing squad the following week.

This week is rightly a time of commemoration and celebration in Ireland. The brutality of the British response galvanized the Irish people – among whom the uprising had initially been unpopular. The tragedy of the Easter Rising thus led to Irish freedom and, after many more decades, ultimately to peace.

It’s a long and brutal road, but amid all the world’s horrors, confronted by man’s undeniable inhumanity to man, perhaps it is well to remember: we do have the capacity for change.

the limits of civic life

(Phoenix, AZ), While I am here today as a guest of Arizona State, I will give a version of the following talk:

The video summarizes my view of civic life in about 10 minutes. By “civic life,” I mean applying our minds, voices, and bodies to improving the world. We can do that alone, but inevitably civic life is collaborative, because individuals rarely achieve much alone and because we need other people’s opinions and perspectives to inform our goals and values.

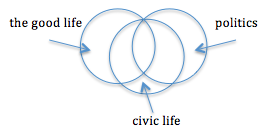

Civic life is important, but it is by no means the only important thing. It represents one circle in this Venn diagram, which also includes circles for politics–meaning all the ways that human beings govern ourselves and create a common world–and the good life.

In civic life, certain ways of interacting are possible and desirable. We can and should be highly interactive while we are in smallish groups dedicated to improving the world. We can be responsive to one another’s needs and opinions and strive act in concert.

But a good life should sometimes be solitary and inward-looking, or directed to nature or God instead of fellow citizens. And politics should sometimes involve competition instead of deliberation and cooperation. For instance, we want incumbent politicians to be regularly challenged by outsiders who criticize them and strive to unseat them. We don’t want incumbents to get too cozy with their challengers. The same is true of business competitors and contending attorneys.

In the video, I argue—and I strongly believe—that civic engagement can enrich our inner lives and offer us psychological and spiritual benefits. But so can non-civic activities, such as observing and appreciating nature, understanding and making art, or loving and caring for other people intimately. Although I think that the spiritual benefits of civic life are often overlooked—and improving our civic culture would strengthen those benefits—I still resist the argument that the good life equals civic engagement.

Here is a typically subtle case: I love to walk in the woods with my family and dog. Enjoying those loved ones in a natural setting is not a form of civic engagement. However, it is only thanks to the Massachusetts Audubon Society and our state government—and the individuals who work in or with those organizations—that the woods have been preserved and opened for us to use. The worthy activity (a family walk) is not civic, yet it depends upon other people’s civic engagement. Still, it’s far too narrow a view of nature and of intimate personal relations to reduce them to products of civic life.

By the same token, civic life doesn’t exhaust politics or offer adequate means to improve politics. Large, impersonal institutions—such as markets and companies, governments and armies, and scientific and technical disciplines—play leading roles in 21st century politics. You and I have limited leverage over these institutions. We can form opinions about what they should do, but those opinions do not always imply meaningful actions for us to take.

If the institution in question is the United States government, I have a tiny but greater-than-zero form of leverage in the form of my vote. If the institution is Coca-Cola, I can decide whether to purchase its products or not. Allocating votes and money are worthwhile acts but hardly constitute a robust civic life. And if the institution in question is the Chinese Government or the market for oil rigs, my leverage approaches zero. In the video, I say that citizens ask, “What should we do?” rather than “What should be done?” But sometimes reasonable people realize that something should be done and yet cannot find anything to do about it themselves. That is the zone of politics that lies outside of civic life in the Venn diagram above.

In the video and almost all my work, I emphasize that “small groups of thoughtful and committed citizens” have the capacity and responsibility to change large systems. I began my professional career helping to advocate for political reform as a research associate at Common Cause, and while I worked there, Common Cause was losing its membership base due to the shrinkage of American civil society that Robert Putnam would soon diagnose in “Bowling Alone” (1995). I came to think that American politics was corrupt because citizens were not adequately organized and active, and I have spent the subsequent two decades working on civic engagement as a precondition for better government. Still, political reform eludes us in the face of hostile Supreme Court decisions, technological developments, and tenacious political opposition. When reform does come, it may be because of a massive scandal or a well-placed leader, not directly because of active citizens. In some other countries and in global markets, the scope for civic life is even narrower than it is in the US.

To discount the importance of citizens in politics is cynical, but to imagine that intentional civic action is all of politics is naive. To the extent we can, we should work to expand the overlap, so that civic life is more politically influential as well as more spiritually rewarding. But I think we will always be left with two hard questions (among others):

- How should we think and act and feel when bad systems are genuinely beyond our control? The Stoic and classical Indian answer was: seek equanimity and acceptance. Epictetus advised: “For if the essence of the good lies in what we can achieve, then there is no space for ill-will or jealousy. Rather, for yourself, don’t strive to be a general or an office-holder or a leader/consul, but to be free. The only road to that is contempt for things not in your power [XIX].” I am unsatisfied with that answer, because I think we have responsibilities to the world even when we cannot see a direct way to address its problems. But what are those responsibilities, exactly? And …

- When an aspect of the good life conflicts with civic responsibilities, how should we choose between them?

DOJ Community Relations Service is Hiring Conciliators

Last week, Grande Lum – the former director of the Dept. of Justice’s Community Relations Service (CRS) and a keynote speaker at NCDD 2014 – shared on an announcement on our NCDD Discussion Listserv about a couple job openings at the CRS that we wanted to mention here, too.

The CRS is hiring for Conciliation Specialists, and we encourage our NCDD members to apply or share about the opportunity with people in your networks. The CRS seeks to serve as a neutral convener and mediator for communities dealing with conflict, and we know that some of our members would make great additions to their national staff.

The CRS is hiring for Conciliation Specialists, and we encourage our NCDD members to apply or share about the opportunity with people in your networks. The CRS seeks to serve as a neutral convener and mediator for communities dealing with conflict, and we know that some of our members would make great additions to their national staff.

Here’s how the CRS describes the positions:

Are you interested in a rewarding and challenging career? Join the U.S. Department of Justice!

The Department of Justice (DOJ), Community Relations Service (CRS) is seeking to hire highly qualified Conciliation Specialists for various Regional Offices. CRS has responsibility for assisting state and local units of government, private and public organizations, and community groups with preventing and resolving racial and ethnic tensions, incidents, and civil disorders, and in restoring racial stability and harmony.

You can find the job announcements at www.usajobs.gov/GetJob/ViewDetails/431163900 and

www.usajobs.gov/GetJob/ViewDetails/431163900. But the deadline to apply is Monday, April 4th, so if you think you’re a good fit for this position, be sure to apply soon!

Good luck to all the applicants!

Společenská burza

Case: Společenská burza

Populism and Democracy

Yesterday, I discussed some of the concerns Walter Lippmann raised about entrusting too much power to “the people” at large.

Such concerns are near blasphemy in a democratically-spiritual society, yet I consistently find myself turning towards Lippmann as a theorist who eloquently raises critical issues which, in my view, have yet to be sufficiently addressed.

At their worst, Lippmann’s arguments are interpreted as rash calls for technocracy: if “the people” cannot be trusted, only those who are educated, thoughtful, and qualified should be permitted to voice public opinions. In short, political power should rightly remain with the elites.

I find that to be a misreading of Lippmann and a disservice to the importance of the issues he raises.

In fact, Lippmann’s primary concern was technocracy – the governing of an elite caring solely for their own interests and whose power ensured their continued dominion. Calling such a system “democracy” merely creates an illusion of the public’s autonomy, thereby only serving to cement elites’ power.

I do not dispute that Lippmann finds “the public” wanting. He clearly believes that the population at large is not up to the serious tasks of democracy.

But his charges are not spurious. The popularity of certain Republican candidates and similarly fear-mongering politicians around the world should be enough to give us pause. The ideals of democracy are rarely achieved; what is popular is not intrinsically synonymous with what is Good.

This idea is distressing, no doubt, but it is worth spending time considering the possible causes of the public failures.

One account puts this blame on the people themselves: people, generally speaking, are too lazy, stupid, or short sighted to properly execute the duties of a citizen. This would be a call for some form of technocratic or meritocratic governance – perhaps those who don’t put in the effort to be good citizens should be plainly denied a voice in governance.

Robert Heinlein, for example, suggests in his fiction that only those who serve in the military should be granted the full voting rights of citizenship. “Citizenship is an attitude, a state of mind, an emotional conviction that the whole is greater than the part…and that the part should be humbly proud to sacrifice itself that the whole may live.”

Similarly, people regularly float the idea of a basic civics test to qualify for voting. You aren’t permitted to drive a car without proving you know the rules of the road; you shouldn’t be allowed to vote unless you can name the branches of government.

Such a plan may seem reasonable on the surface, but it quickly introduces serious challenges. For generations in this country, literacy tests have been used to disenfranchise poor voters, immigrants, and people of color. And even if such disenfranchisement weren’t the result of intentional discrimination – as it often was – the existence of any such test would be biased in favor of those with better access to knowledge.

That is – those with power and privilege would have no problems passing such a test while our most vulnerable citizens would face a significant barrier. To make matters worse, these patterns of power and privilege run deeply through time – a civics test for voting quickly goes from a tool to encourage people to work for their citizenship to a barrier that does little but reinforce the divide between an elite class and non-elites.

And this gives a glimpse towards another explanation for the public’s failure: perhaps the problem lies not with “the people” but with the systems. Perhaps people are unengaged or ill-informed not because of their own faults, but because the structures of civic engagement don’t permit their full participation.

Lippmann, for example, documented how even the best news agencies fail in their duty to inform the public. But the structural challenges for engagement run deeper.

In Power and Powerlessness, John Gaventa documents how poor, white coal miners regularly voted in local elections – and consistently voted for those candidates supported by coal mine owners. These were often candidates who actively sought to crush unions and worked against workers rights. Any fool could see they did not have the interest of the people at heart…but the people voted for them anyway, often in near-unamous elections.

To the outsider, these people seem stupid or lazy – the type whose vote should be taken away for their own good. But, Gaventa argues, to interpret that is to miss what’s really going on:

Continual defeat gives rise not only to the conscious deferral of action but also to a sense of defeat, or a sense of powerlessness, that may affect the consciousness of potential challengers about grievances, strategies or possibilities for change….From this perspective, the total impact of a power relationship is more than the sum of its parts. Power serves to create power. Powerlessness serves to re-enforce powerlessness.

In the community Gaventa studied, past attempts to exercise political voice dissenting from the elite had lead to people loosing their jobs and livelihoods. If I remember correctly, some had their homes burned and some had been shot.

It had been some time since such retribution had been taken, but Gaventa’s point is that it didn’t need to be. Elites had established their control so thoroughly, so completely, that poor residents did what was expected of them without hardly a thought. They didn’t need to be threatened so rudely; their submission was complete.

Arguably, theorists like Lippmann see a similar phenomenon happening more broadly.

If you are deeply skeptical of the system, you might believe it to be set up intentionally to minimize the will of the people. In the States at least, our founding fathers were notoriously scared of giving “the people” too much power. They liked the idea of democracy, but also saw the flaws and dangers of pure democracy.

In Federalist 10, James Madison argued:

From this view of the subject it may be concluded that a pure democracy, by which I mean a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert result from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths. Theoretic politicians, who have patronized this species of government, have erroneously supposed that by reducing mankind to a perfect equality in their political rights, they would, at the same time, be perfectly equalized and assimilated in their possessions, their opinions, and their passions.

To give equal power to all the people is to set yourself up for failure; to leave nothing to check “an obnoxious individual.”

Again, there is something very reasonable in this argument. I’ve read enough stories about people being killed in Black Friday stampedes to know that crowds don’t always act with wisdom. And yet, from Gaventa’s argument I wonder – do the systems intended to check the madness of the crowd rather work to re-inforce power and inequity; making the nameless crowd just that more wild when an elite chooses to whip them into a frenzy?

Perhaps this system – democracy but not democracy – populism but not populism – is self-reinforcing; a poison that encourages the public – essentially powerless – to use what power they have to support those crudest of elites who prey on fear hatred to advance their own power.

As Lippmann writes in The Phantom Public, “the private citizen today has come to feel rather like a deaf spectator in the back row …In the cold light of experience he knows that his sovereignty is a fiction. He reigns in theory, but in fact he does not govern…”