Monthly Archives: February 2016

Bernie Sanders Brings Back ‘Yes We Can’ Progressivism

Bernie Sanders Brings Back ‘Yes We Can’ Progressivism

The contrast between "we" and "I" has old roots in the progressive tradition. Debates about "socialism" are a diversion -- both Sanders and Clinton have legitimate claims to be progressive. But they represent different strands of the progressive tradition: the expert tradition and the populist tradition.

Progressivism emerged in the late 19th century and early 20th century as a movement to roll back the excesses of Gilded Age capitalism. Progressives believed in a positive role for government in taming the market. They believed in the principle of social change. They valued science. They affirmed the intrinsic worth and dignity of human beings.

But as David Thelen, past editor of the Journal of American History and a leading historian of progressivism, argued in his essay "Two Traditions of Progressive Reform" and other works, beyond these general agreements were two different tendencies. One was oriented toward bureaucracy and expert decision-making; the other was more populist, focused on grassroots democracy and participation.

Donna Shalala -- longtime Hillary Clinton confidant, secretary of health and human services during President Bill Clinton's administration and now president of the Clinton Foundation -- expressed clearly the tenets of the expert tradition back in 1989, in "Mandate for a New Century," a now-famous speech she delivered as chancellor of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Shalala called upon higher education to engage with the problems of the world, from racism and sexism to environmental degradation, war and poverty. She also voiced the view that scientifically trained experts -- "a disinterested technocratic elite" -- should be at the center of decision-making. As Shalala put it:

"The idea of society's best and brightest in service to its most needy, irrespective of any particular political philosophy ... is an idea of such great elegance... We all need to see our gifted researchers set about the work that will eliminate the cripplers we face now as thoroughly, if not as swiftly, as our research eliminated juvenile rickets in the past."

Hillary Clinton's "fighting for you" channels these expert-driven ideas. It places Clinton in the role of savior of the disadvantaged and marginalized -- Shalala's "best and brightest in service to its most needy." Clinton's calls for collective effort also suggest expert consultation. "We've got to get our heads together to come up with the best answers to solve the problems so that people can have real differences in their lives," Clinton said in her concluding remarks in a debate with Sanders on February 4, 2016.

However, the democratic tradition of progressivism has long been animated by populist movements: labor union organizing, civil rights, educational reform, the struggles of farmers to keep their farms and other such crusades. Progressive intellectuals with a grassroots democratic bent like Jane Addams, John Dewey, A. Philip Randolph and Alain Locke all had strong ties to these movements. So too did Henry Wallace, Franklin Roosevelt's secretary of agriculture and then-vice president, who in 1942 delivered a speech entitled "Century of the Common Man." Wallace's speech explicitly challenged Life publisher Henry Luce's "American Century" essay of 1941, which claimed warrant for America as global policeman.

Wallace's tenure as secretary of agriculture also encompassed a little-remembered but enormous effort to democratize decision-making around how American farmland is used, from 1938 to 1941. Detailed in Jess Gilbert's 2015 book Planning Democracy, this movement showed how participatory democracy could take place with government acting as an empowering partner to its citizens -- neither savior nor enemy.

This populist, small-D democratic tradition of progressivism was revived in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. It surfaced again in the community-organizing movement of the 1970s and 1980s, which fundamentally shaped a young Barack Obama in Chicago.

Obama took the message of grassroots democracy which he had learned from community organizing to the nation in the 2008 campaign, amplifying its themes and engaging millions of people. "I'm asking you not only to believe in my ability to make change," read the campaign website. "I'm asking you to believe in yours." The message was expressed in such memorable campaign slogans as, "We are the ones we've been waiting for," drawn from a song of the freedom movement of the 1960s. And it infused Obama's field operation. As Rolling Stone reporter Tim Dickinson noted in "The Machinery of Hope," the goal was "not to put supporters to work but to enable them to put themselves to work, without having to depend on the campaign for constant guidance." "We decided that we didn't want to train volunteers," Obama field director Temo Figueroa explained to Dickinson. "We want to train organizers -- folks who can fend for themselves."

After Obama took office, the democratic promise of his campaign remained largely unrealized. Indeed, after becoming president, Obama's language began to shift from "we" to "I." At the news conference marking the first 100 days of his administration, Obama was asked what he intended to do as chief shareholder of some of America's largest companies. "I've got two wars I've got to run already," he laughed. "I've got more than enough to do." This shift in pronouns paralleled the deactivation of the grassroots base of Obama for America (OFA), which had powered the campaign.

As of election night 2008, OFA included some 2.5 million activists in the My.BarackObama social network, four million donors and 13 million email supporters. After the election, the organization's name shifted to "Organizing for America," at which point a fierce argument erupted among campaign leaders. Deputy campaign manager Steve Hildebrand argued that the new OFA should become an independent nonprofit. Joe Trippi, campaign manager for 2004 Howard Dean race, observed that OFA and its supporters had many independents and some Republicans and shouldn't lose its cross-partisan qualities. Finally, David Plouffe, a key architect of the 2008 campaign was put in charge of OFA. He decided to incorporate the organization as part of the Democratic National Committee.

"The move meant that the machinery of an insurgent candidate, one who had vowed to upend the Washington establishment, would now become part of that establishment, subject to the entrenched, partisan interests of the Democratic Party," observed Rolling Stone's Dickinson in "No We Can't." "It made about as much sense as moving Greenpeace into the headquarters of ExxonMobil."

Flash forward to 2016, and we find the Democratic campaign tapping into growing activism on many fronts -- from Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter to action on climate change and local development.

Bernie Sanders' core argument, that a grassroots movement will be necessary for real change, echoes the Obama 2008 message, both in its stress on participatory democracy and in its integration of a range of issues into a larger call for change -- "we" language, not "I" language. In his speech after the Iowa caucuses, Sanders said. "The powers that be... are so powerful that no president can do what has to be done alone... When millions of people come together... to stand up and say loudly and clearly, 'Enough is enough'... when that happens, we will transform this country."

Should Sanders become president, he might well pursue a broad activation of citizens. "Bernie Sanders has always identified with the populist side of progressivism," Huck Gutman, Sanders's chief of staff in the Senate from 2008 to 2012, told me.

It is still possible that Hillary Clinton could pick up themes from the Reinventing Citizenship project I coordinated with Bill Galston, deputy assistant for domestic policy to President Bill Clinton from 1993 to 1995, now of the Brookings Institution. Reinventing Citizenship proposed a number of measures to strengthen government as a partner of citizens in public problem-solving and the work of democracy.

Whatever the outcome of the contest between Clinton and Sanders, the key to real change is the people. The issues that the campaign has raised -- the power of Wall Street, economic inequality and stagnant wages, college debt, mass incarceration, universal health care, campaign finance reform, climate change and others -- will require citizen power on a large scale if fundamental change is to occur.

There are also many other, large-scale issues, crucial to the fate of the nation, that scramble partisan lines: revitalization of the democratic purpose of education; local economic development in the face of radical technological change; the drug epidemic; and reweaving the social fabric in a time of eroding community ties, to name just a few. These are enormous challenges. If the Democratic debate continues and deepens the call for citizen activation, it could well catalyze civic efforts beyond the issues of the campaign.

It is also clear that the idea of "we" has found a resonant audience especially among young people. "Sanders gives young people a place in his campaign," wrote Elisabeth Bott, one of my students from the University of Minnesota. "For so many people, politics is tainted. Sanders's campaign restores the idea that politics can be a source of change. He understands that we live in a time of change and extreme injustice and wants to change that with the help of us all."

This idea is not Sanders' alone. Politics -- by the definition of the term dating from the Greeks until the modern era -- has long involved citizens of diverse views and interests learning to work together to solve common problems, create common good and negotiate a democratic way of life. If we are to reverse the deepening mood of discouragement and powerlessness in the nation, we need wide civic involvement, amounting to a democratic awakening.

In this election, perhaps we see its beginnings.

This column was originally published in BillMoyers.com, February 17.

Bernie Sanders Brings Back ‘Yes We Can’ Progressivism

Bernie Sanders Brings Back ‘Yes We Can’ Progressivism

At Franklin Pierce, Learning to Make a Difference (Connections 2015)

The two-page article, At Franklin Pierce, Learning to Make a Difference, by Joni Doherty was published Fall 2015 in Kettering Foundation‘s annual newsletter, “Connections 2015 – Our History: Journeys in KF Research”. Doherty shares about the New England Center for Civic Life at Franklin Pierce University, and its focus on teaching and deliberation. Find the full article below, and Connections 2015 is available for free PDF download on Kettering’s site here.

From the article…

The New England Center for Civic Life at Franklin Pierce University is dedicated to the teaching, practice, and study of deliberative democracy. As director of the center, I helped align the center’s mission with that of the university. The center was founded in 1998 on the premise that engaged and deliberative communities are vital for a healthy democracy and for individuals to realize their goal of experiencing rich and fulfilling lives. Through initiatives that use deliberative democratic practices, the center creates opportunities for people to become active producers of knowledge and engaged community members. At first, our efforts were divided between community-based and campus-based work; today, about threequarters of the center’s activities are on campus. We learned that the best way to realize the center’s mission was to meet people where they are, and where we are too—on a rural, small, liberal arts college campus.

The New England Center for Civic Life at Franklin Pierce University is dedicated to the teaching, practice, and study of deliberative democracy. As director of the center, I helped align the center’s mission with that of the university. The center was founded in 1998 on the premise that engaged and deliberative communities are vital for a healthy democracy and for individuals to realize their goal of experiencing rich and fulfilling lives. Through initiatives that use deliberative democratic practices, the center creates opportunities for people to become active producers of knowledge and engaged community members. At first, our efforts were divided between community-based and campus-based work; today, about threequarters of the center’s activities are on campus. We learned that the best way to realize the center’s mission was to meet people where they are, and where we are too—on a rural, small, liberal arts college campus.

One challenge we faced was connecting the self-interested, personal goals of undergraduates, who understandably are preoccupied with doing well academically and preparing for their future professions, with the larger public good. We also faced the challenge of the workload of faculty, who teach four courses each semester. There is often little time for civic, cocurricular, or extracurricular activities.

We learned that if we were to engage these groups, we needed to become involved in their primary areas of concern. With that in mind, we began the work of integrating deliberative practices (including identifying issues on one’s own terms, and on what is held valuable; considering possible actions; and making sound judgments through weighing benefits against trade-offs) into courses and the curriculum, not as “extras” or “supplements,” but rather as activities essential for teaching and learning in a democratic society. These practices foster critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and good communication skills and are done within an environment that encourages collective learning.

Engagement through Community

These practices can foster deeper engagement through connecting course content with community life. Examples include having students participate in a deliberative forum on a community problem that is relevant to course content; creating an issue guide with various options for addressing a problem; ensuring diverse perspectives are represented in course assignments (readings, films, and so on); and presenting ethical dilemmas in ways that invite the consideration of multiple options. Because deliberative pedagogy recognizes the impact of self-interest on engagement, affirms the value of personal experiences, and takes up “real-life” problems, it integrates formal education with the “subject matter of life-experience,” which John Dewey has identified as an essential part of learning.

Our first major initiative was the Diversity and Community Project, which began in 1998. Faculty and students created guides on issues related to gender, sexual orientation, and race. We also used the National Issues Forums racial and ethnic tensions guide to situate our campus issue within a broader national context. We held annual moderator and issue-framing workshops, led class-based and campuswide forums, and began a Civic Scholars program. The project was integrated into the first-year seminar. A grant allowed us to share what we had learned with other colleges in northern New England. Over time, these activities became integral to all of the center’s programming.

Another example of curricular integration, and one that connects courses across the disciplines, is the Art and Dialogue Project, which focused on a different issue for each of its five years. Our first project, in 2010, explored a water-related environmental issue. In following years, we took on other challenges, including respect (or lack thereof ) in public life. This project includes creating a public participatory art installation, which, along with concerncollecting sessions, is part of how we name and frame the issue, and convening forums. It culminates in a multimedia celebration that has included video, music, light and sound installations, and storytelling. This is not a programmatic sequence of individual performances, but one in which the public (in this case, students) are cocreators of a deliberative public exchange. It is a way for students to transform the everyday routines of college life into one in which they are the primary actors and agents for change.

As one of the university’s primary community liaisons, the center also partners with towns and local residents on projects. Because they do not follow academic schedules, faculty and student involvement tends to be episodic, and having a full-time, year-round director ensures the necessary continuity. In “Rindge 2020: Mapping Our Future,” town officials from Rindge, university faculty, and local residents framed the issue, wrote a guide, held forums, and implemented several actions. Another example, “Citizens Seeking Common Ground,” involved residents in a school district that spanned two towns. The group held a series of dialogues to work out a way of addressing a six-year impasse on the need for new or improved school facilities.

About Kettering Foundation and Connections

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

Each issue of this annual newsletter focuses on a particular area of Kettering’s research. The 2015 issue, edited by Kettering program officer Melinda Gilmore and director of communications David Holwerk, focuses on our yearlong review of Kettering’s research over time.

Follow on Twitter: @KetteringFdn

Resource Link: www.kettering.org/sites/default/files/periodical-article/Doherty_2015.pdf

Pluribus Project Seeks Narrative Projects & Ideas to Fund

We strongly encourage our NCDD members to take note that the Aspen Institute’s Pluribus Project is calling for projects and ideas aimed at changing the national narrative about citizen participation that it wants to fund with grants of up to $50,000, and we know many of our members could be eligible. All are encouraged to apply for this great opportunity, but the deadline is March 15th, so don’t delay! Read more in the Pluribus Project’s announcement below or find the original here.

Pluribus Project Narrative Collaboratory: Open Call For Fundable Projects

Our nation’s founders envisioned a republic in which the people would be the ultimate source of power. Today, however, a pervasive cultural narrative – across the right and the left – tells Americans it is pointless to participate in civic life because the game is rigged and their voices just don’t matter. At the Pluribus Project, we believe that it’s time to counter this dominant negative narrative and to displace it with a storyline of citizen empowerment so that Americans can begin to see that change is possible and how to become a part of it.

Our nation’s founders envisioned a republic in which the people would be the ultimate source of power. Today, however, a pervasive cultural narrative – across the right and the left – tells Americans it is pointless to participate in civic life because the game is rigged and their voices just don’t matter. At the Pluribus Project, we believe that it’s time to counter this dominant negative narrative and to displace it with a storyline of citizen empowerment so that Americans can begin to see that change is possible and how to become a part of it.

The reality is that many Americans in communities across the country are finding ways to come together and create real change. They may be a minority but they are not uncommon and they are still noticeably absent from the mainstream conversation. That’s why we created the Narrative Collaboratory, a platform for generating and propagating new narratives of citizen voice and efficacy, coupled with the tools of power and action that others can use. Think of it as a venture platform to seed experiments in media, storytelling, organizing, and experience design.

We are now announcing an Open Call for experiment and project ideas. We intend to select and support multiple proposals that creatively and effectively spread narratives of citizen power. Selected projects will be eligible for financial support, ranging from $5,000 to $50,000, from the Pluribus Project, and will be featured to additional donors and potential supporters through various media and events including the Aspen Ideas Festival.

Ultimately, we believe that with a sense of collective purpose, some trial and error, and the ingenuity of the many (that’s you), there is real opportunity right now to reinvent our civic reality, and to help create a more representative and responsive democracy.

SELECTION CRITERIA

Promise: All projects should show great promise to counter the pervasive, disheartening narrative that discourages citizens from engaging in their democracy. We are looking for platforms for experimentation that can generate or propagate new, durable, and contagious narratives of citizen power and efficacy.

A Diversified Portfolio: We are looking for projects that are diverse in type. Some may be media ventures, involving traditional journalism, digital media, or social media. Some might be organizing initiatives. Others might political ideation ventures. Some may even be hybrids. All projects must be non-partisan, and we prefer projects that are trans-partisan.

Scalable with a proof of concept: We are structure-agnostic – meaning that we will consider both for-profits and nonprofits. We generally prefer ventures with demonstrated proof of concept and a clear plan for reach and sustained impact. All funded ventures will be required to enter into a formal written agreement with the Pluribus Project, committing to use grant funds for specific purposes—including the charitable and educational ends—outlined in their proposal.

SELECTION PROCESS

Applications are due March 15, 2016. We will choose a set of projects to fund by April 15 and these projects will be implemented through the calendar year.

Applications will be reviewed and evaluated by a team of experts in civic engagement, innovation, and investment. The final portfolio will be financed at the discretion of the Pluribus Project Narrative Collaboratory team, who will receive advice and input of the experts engaged throughout the process.

TO APPLY

Please answer the following questions. Email your answers to narrative@pluribusproject.org. You may also include relevant attachments. The deadline for applications is March 15, 2016.

(1) Describe the narrative project or experiment. What exactly are you are doing, or do you plan to do, in order to generate or propagate new, durable, and contagious narratives of citizen power and efficacy? (500 words max.)

(2) How will you use the money and why will your project benefit from this investment? (250 words max.)

(3) What results have you achieved to date (if applicable), and what results do you anticipate for the next year? (250 words max.)

(4) Please provide brief bios for each core team member.

You can find the original version of this Pluribus Project announcement at www.pluribusproject.org/news/narrative-collaboratory-open-call.

A Quick Look at Three Ways to Approach Picture Analysis

As educators, we are always looking for new ways to approach our content and engage our students. A few weeks ago, the FJCC had the pleasure of providing professional development to teachers in Highlands County, a small rural county here in Florida very similar to where your humble blog host spent much of his early career. While there, I had the chance to speak with Holly Ard. Holly basically functions as the social studies specialist in the district while still teaching her own classes, and does excellent work.

One of the most difficult tasks for students to do, particularly at the lower grades, is to interpret primary sources, especially visual sources. While we stress the importance of primary sources, we often fail to actually provide teachers or students with the tools necessary to use them! This, in a time when disciplinary literacy has re-emerged as an important element of social studies teacher education thanks in part to the C3 Framework. Holly has attempted to address this issue by integrating a Picture Analysis Strategy. The strategy she uses is aimed at students of differing ability levels, and in talking with her, it seems to work well in engaging students with somewhat difficult content!

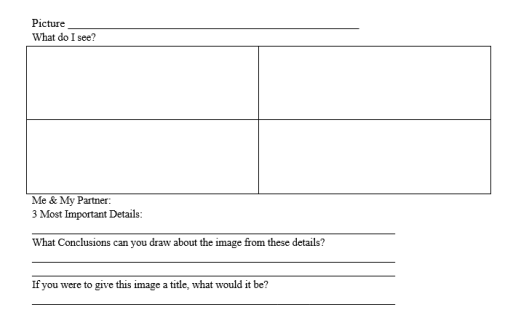

Working with partners, students individually break down the image, using the guide below. Note that the four ‘boxes’ represent the four quadrants of the image, a popular approach for image analysis. Having students create a title for the image does a nice job getting to the Common Core/Florida Standards expectation that students should be able to summarize text of all kinds. What else is a good a title than a really short and really strong summary of text?

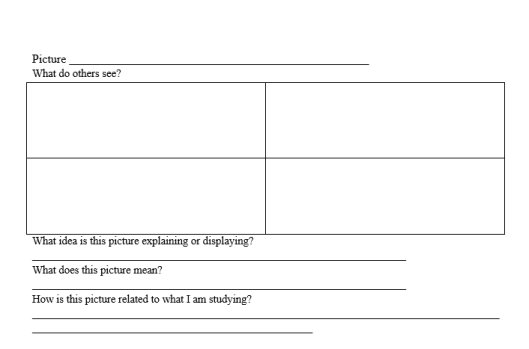

Another way to approach image analysis is seen below. This version of the analysis template can be done with a partner or individually. I appreciate how it seeks to have students connect it directly to what they are learning. Relations between content and context is important.

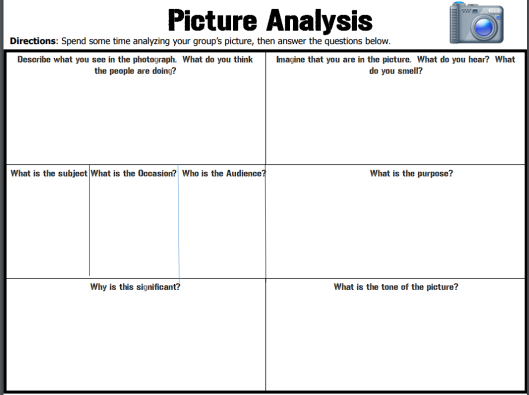

I especially love this version of the picture analysis activity, which may be most useful for paintings or photographs of a perhaps persuasive bent.

Thanks, Holly, for sharing these approaches. We look forward to more goodness from you!

By the way, if you are looking for resources in Civics or History that can help kids with primary sources, I encourage you to check out the Stanford History Education Group!

Mimicking Deliberation

In 1950, pioneering computer scientist Alan Turing described an “imitation game” which has since come to be known as the Turing Test. The test is a game played between three agents: two humans and a computer. Human 1 asks a series of questions; human 2 and the computer respond.

The game: human 1 seeks to correctly identify the human respondent while human 2 and the computer both try to be identified as human.

Turing describes this test in order to answer the question: can machines think?

The game, he argues, can empirically replace the posed philosophical question. A computer which could successfully be regularly be identified as human based on its command of language would indeed “think” in all practical meanings of the word.

Turing goes on to address the many philosophical, theological, and mathematical objections to his argument – but that is beyond the scope of what I want to write about today.

Regardless of the test’s indication for sentience, it quickly became a sort of gold standard in natural language processing – could we, in fact, build a computer clever enough to win this game?

Winning the game, of course, requires a detailed and nuanced grasp of language. What orders are properly appropriate for words? What elements of a question ought a respondent repeat? How do you introduce new topics or casually refer to past topics? How do you interact naturally, gracefully engaging with your interlocutor?

Let’s not pretend that I’ve fully mastered such social skills.

In this way, designing a Turing-successful machine can be seen as a mirror of ideal speaking. The winner of the Turing game, human or machine, will ultimately be the player who responds most properly – accepting some a nuanced definition of “proper” which incorporates human imperfection.

This makes me wonder – what would a Turing Test look like specifically in the context of political deliberation? That is, how would you program ideal dialogue?

Of course, the definition of ideal dialogue itself is much contested – should each speaker have an exactly measured amount of time? Should turn-taking be intentionally delineated or occur naturally? Must a group come to consensus and make a collective decision? Must there be an absence of conflict or is disagreement a positive signal that differing views are being justly considered?

These questions are richly considered in the deliberation literature, but it takes on a different aspect somehow in the context of the Turing Test.

Part of what makes deliberative norms so tricky is that people are, indeed, so different. A positive, safe, productive environment for one person may make another feel silenced. There are intersecting layers of power and privilege which are impossible to disambiguate.

But programming a computer to deliberate is different. A machine enters a dialogue naively – it has no history, no sense of power nor experience of oppression. It is the perfect blank slate upon which an idealized dialogue model could be placed.

This question is important because when trying to conceive of ideal dialogue run the risk of making a dangerous misstep. In the days when educated white men were the only ones allowed to participate in political dialogue, ideal dialogue was easier. People may have held different views, but they came to the conversation with generally equal levels of power and with similar experiences.

In trying to broaden the definition of ideal dialogue to incorporate the experiences of others who do not fit that mold, we run the risk of considering this “other” as a problematizing force. If we could just make women more like men; if we could make people of color “act white,” then the challenges of diverse deliberation would disappear.

No one would intentionally articulate this view, of course, but there’s a certain subversive stickiness to it which has a way of creeping in to certain models of dialogue. A quiet, underlying assumption that “white” is the norm and all else must change to accommodate that.

Setting out to program a computer changes all that. It’s a dramatic shift of context which belies all norms.

Frankly, I hardly know what an ideal dialogue machine might look like, but – it seems a question worth considering.

Dialogues Across Differences: An Introduction to Reflective Structured Dialogue

This partial-day workshop, Dialogues Across Differences: An Introduction to Reflective Structured Dialogue, from Public Conversation Project and has been developed over the last two decades. The dialogue process established in this training creates an opportunity to transform communication between participants who have conflict. Below is the description from Public Conversations Project and check out if there are upcoming workshop dates here on their site.

About the workshop…

Summary:

25 years ago, Public Conversations Project created a unique approach to dialogue that promoted connection and curiosity between those who saw one another as the enemy. Our approach has transformed conflicts across the country and the world – but its principles are widely applicable for everyday conversation. An intentional communication process can help individuals, organizations and communities build trust, enhance resilience for addressing future challenging issues, and have constructive conversations with those they otherwise “wouldn’t be caught dead with.”

Learning Objectives:

- Learn basic theory and practice of Public Conversations’ relationship-centered approach to better communication and dialogue.

- Achieve shared, clear, and mutually understood purpose in a conversation.

- Design a framework for a constructive conversation that will encourage people to participate fully, listen actively, and enhance empathy.

- Stimulate self-discovery and curiosity about the “other” through questions that promote connection, curiosity and caring.

Results:

As a result of this workshop, you will be equipped to:

- Communicate with self-confidence about difficult or divisive topics.

- Break destructive communication habits like avoidance, silence, or reactive responses, enabling those in a conversation to feel truly listened to.

- Design conversations, dialogues, or meetings with clear purpose, full participation, and a structure for moving forward.

- Employ effective and satisfying communication exercises in a broad range of personal and professional settings.

Who might participate:

- Executives in the nonprofit, public, or private sectors interested in shifting the culture of communication in their workplace.

- Managers seeking to lead more constructive conversations with a divided, frustrated, or distracted team.

- Clergy looking to broach a challenging concept with their congregation or internal leadership.

- Consultants in strategic communications, strategic planning, or organizational development exploring new ways to improve client relations.

- Administrators seeking to encourage collaboration between departments.

Accreditation:

This workshop is approved for 6 clock hours for national certified counselors, Massachusetts licensed mental health counselors, MA licensed marriage and family therapists, and New Hampshire pastoral psychotherapists. Credits are accepted by the NH Board of Mental Health Practice for all licensed NH mental health professionals. For more information, please see our workshop policies. Public Conversations Project is an NBCC-Approved Continuing Education Provider (ACEP™) and may offer NBCC-approved clock hours for events that meet NBCC requirements. The ACEP solely is responsible for all aspects of the program.

For more information, please contact us at training[at]publicconversations[dot]org or 617-923-1216 ext. 10.

About Public Conversations Project

Public Conversations Project fosters constructive conversation where there is conflict driven by differences in identity, beliefs, and values. We work locally, nationally, and globally to provide dialogue facilitation, training, consultation, and coaching. We help groups reduce stereotyping and polarization while deepening trust and collaboration and strengthening communities.

Follow on Twitter: @pconversations

Resource Link: www.publicconversations.org/workshop/dialogue-across-differences-introduction-reflective-structured-dialogue