Monthly Archives: February 2016

Women’s Forum and Workshop for the Development of a Local Equality Action Plan for Kadikoy

Sanders dominates the Iowa youth vote

Below is CIRCLE’s press release from this morning. Additional data can be found on the website.

Young Democrats Propel Sanders to Virtual Tie in Iowa; Record-breaking Participation Among Young Republicans, who Choose Cruz, Rubio Over Trump

Medford/Somerville, MA – Youth turnout in last night’s Iowa caucuses is estimated to be 11 percent, according to youth vote experts from the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning & Engagement (CIRCLE) – the preeminent, non-partisan research center on youth engagement at Tufts University’s Jonathan M. Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service.

Highlights of the youth vote in Iowa include:

- An estimated 11.2% of eligible Iowan youth aged 17 to 29 participated in last night’s Republican and Democratic caucuses.

- On the Democratic side, the youth choice was decisive. Of the estimated 31,000 young people who participated in the Democratic caucus, 84% supported Senator Bernie Sanders, contributing to a virtual tie between Secretary Hillary Clinton and Senator Sanders.

- Young Republicans selected Senator Ted Cruz as their top candidate (with 26%), closely followed by Senator Marco Rubio (23%). Youth support for Donald Trump, which came in at approximately 20%, trailed the support he received among older Republicans.

- Since 1996, youth turnout in Iowa has exceeded 4% only twice: in 2008 (14%) and yesterday (11.2%).

- A record-breaking 22,000 young people voted in the Republican caucus.

- About 31,000 young people participated in the Democratic caucus, the second highest level since 1996 (behind 2008).

“Last night’s Iowa caucuses demonstrated the potential power of young people to shape elections,” said Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, Director of CIRCLE. “In the Democratic caucus, young voters helped to propel Senator Sanders to a virtual tie, and Republican youth broke their own record of caucus participation. One message is clear: when candidates and campaigns ask young people to participate and inspire them to get involved, they respond.”

For CIRCLE’s full Iowa caucus analysis, please see here. Throughout this election season, CIRCLE’s 2016 Election Center will offer new data products and analyses – such as a preview of youth participation in the NH primary – providing a comprehensive picture of the youth vote, both nationally and in targeted states and congressional districts across the country. You can view trend data on youth turnout via CIRCLE’s interactive maps.

Public Education as Community Work (Connections 2015)

The four-page article, Public Education as Community Work, by Connie Crockett, Phillip D. Lurie, and Randall Nielsen was published Fall 2015 in Kettering Foundation‘s annual newsletter,“Connections 2015 – Our History: Journeys in KF Research”. The three authors describe the history of how Kettering has studied the politics of education and reveal some of the challenges faced in education today.

In the article, the authors discuss how the Foundation’s founder, Charles F. Kettering had been aware from the beginning how the education of youth and the way in which public education is shaped by its community, was vital for true democracy. The challenges that Kettering identified in the 20’s, that the community must actively take part in shaping education in order for democracy to continue, are still present today. Below is an excerpt from the article. You can find Connections 2015 available for free PDF download on Kettering’s site here.

From the article…

Phil Lurie: Today, it is widely recognized that people are frustrated by the lack of influence they have on the public schools. However, there seems to be little recognition of the potential that exists in the resources outside of schools that could reinforce the work of schooling.

Phil Lurie: Today, it is widely recognized that people are frustrated by the lack of influence they have on the public schools. However, there seems to be little recognition of the potential that exists in the resources outside of schools that could reinforce the work of schooling.

Randall Nielsen: That is what makes the study of the politics of education such a vital part of the foundation’s overarching study of how to make democracy work as it should. The challenges that people face in bringing their collective resources to complementary work in the education of youth are fundamental problems of democracy.

PL: In public policy, and in studies of education, the challenge remains quite narrowly defined. Generally the problem is seen as understanding how people can be more influential in the administration of schools.

Connie Crockett: And how to get people to support the schools, somewhat without question. It is interesting to recall that the foundation’s alternative emphasis on the whole picture of an educating ecology emerged pretty early on at Kettering.

…

CC: Again, the challenge begins with seeing it as a problem of democracy, not a problem of administration of schooling. The public in Mathews’ 1996 book referred not simply to people living in a particular place, but rather to a diverse body of people willing and able to recognize and act on shared concerns. In so doing, they become a responsible public, in which people hold one another accountable to a covenant that has been legitimately decided upon. Our focus on democracy suggests that citizens need to engage one another in the fundamental challenge of choosing “how do we want to educate our youth?” This is where we remain, and we are still looking for innovators and experimenters.

The Current Focus

RN: The foundation’s studies remain focused on the implications of a simple premise. Young people are educated through experiences that occur inside and outside of schools. The educational capacity of a community is defined by the ability to put the mélange of educational resources to work in complementary ways. We explore the governance of educational resources as a fundamental challenge of democratic citizenship.

PL: The problem is that education remains widely seen as the singular responsibility of schools and professionals. Critical roles citizens play and need to play go unrecognized by professionals and nonprofessionals. As education has become schooling, the non-school educational assets in communities have largely disappeared from the naming and framing of public choices about issues that affect the education of youth. Thus professional educators have detached the governance of schools from the governance of the myriad non-school activities that critically affect educational outcomes. Non-school activities remain as an educational force, but they are not often the subject of citizento-citizen judgment and innovation.

RN: The resulting atrophy of educational citizenship—the shared sense that communities of people have the responsibility and power to shape the education of their youth—weakens educational outcomes and reduces public confidence in school institutions. It also weakens the popular sense of the democratic capacity to shape the futures of children. That is a fundamental threat to democracy itself.

PL: The research is now organized into two complementary areas, both studying innovations in practice. One focuses on showing the potential for the education that occurs outside of schools. The other explores way that people can bring the governance of public schooling into the larger context of the governance of all educational resources.

About Kettering Foundation and Connections

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

The Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation.

Each issue of this annual newsletter focuses on a particular area of Kettering’s research. The 2015 issue, edited by Kettering program officer Melinda Gilmore and director of communications David Holwerk, focuses on our yearlong review of Kettering’s research over time.

Follow on Twitter: @KetteringFdn

Resource Link: www.kettering.org/sites/default/files/periodical-article/Crockett-Lurie-Nielsen_2015.pdf

Three Thoughts on Iowa

- I made a series of predictions on the eve of the caucuses that turned out to be wrong. I predicted that Sanders and Trump would win; I placed some small bets on that basis. I was roundly proven wrong, even though some pundits are calling the outcome a “virtual tie” and a few delegates were apparently allocated by coin flip. I respect the Sanders campaign for trying to spin the loss as a victory, but I don’t get to collect on the bet for a virtual tie for the same reason you don’t get to move in to the White House on the basis of a virtual tie.

Now, I wasn’t really confident in either prediction (I say after the fact). I was swayed by a late poll by Ann Selzer that has had a history of being pretty good. So I’m again struck by the value of making probability forecasts rather than predictions: at best that poll shifted my uncertainty on Cruz/Trump and Clinton/Sanders a little bit towards certainty. But it’s also the case that the right attitude before the event really should have been uncertainty: some outcomes were impossible, but several outcomes were live possibilities. The goal really shouldn’t be to gloat or mope after the fact: the goal should be to update your forecasting abilities, to get better at making future predictions.

- The caucus format is deliberative. (More so for the Democrats than the Republicans, but still.) That makes polling somewhat less predictive, because polling can only measure pre-deliberative attitudes. We published a really good account of the issues with polling as a measure of “public opinion” in The Good Society a few years back: Liz Turner’s “Penal Populism, Deliberative Methods, and the Production of ‘Public Opinion’ on Crime and Punishment.” Turner argues that surveys produce only one version of the “hypothetical public” which is aggregative, generalized, individualized, and passive. It can (when properly massaged) produce a good prediction about electoral outcomes, since voting ballots, too, have become aggregative, generalized, individualized, and passive. But even mildly deliberative moments like the Iowa caucuses can lead to surprising outcomes because a very different public (no longer hypothetical) is constituted by the caucus form.

- Finally, the real problem throughout the (Republican) race has been the number of candidates who had some claim to viability. The larger the number of candidates running, the more likely you are to have Condorcet loser (the one who would win the majority of head-to-head ballots) winning the election. Large numbers of (viable) candidates make voting irrational. In Iowa, there were at least six viable Republican candidates measured by delegates, and eleven candidates received at least 1% of the vote. We can see this problem on a much smaller scale with the way that the Clinton campaign planned to use Martin O’Malley as a spoiler, to prevent Sanders from picking up delegates at the margins. That said, I haven’t seen any evidence that this ended up happening, but rather the reverse.

To Revive the American Dream, Work Locally, Work Smart, Work Together

C.A.R.O.N. – Community Alliance to Revitalize Our Neighborhood: Violence Prevention by Engaging Youth and Immigrant Families

San Luis Obispo County: Building Public Support for Needed Infrastructure

City of Vallejo Launches Third Cycle of Participatory Budgeting

we are for social justice, but what is it?

Schools and colleges, daily newspapers and broadcast television channels, and certain civic associations are prone to present themselves as neutral about politics. They say that they provide information, spaces for discussion, and opportunities to learn skills. Their students, readers, or citizen-members are free to form their own opinions.

Activists in social movements observe that these organizations are not truly neutral (but rather full of implicit values) and argue that grave current injustices require all organizations to take explicit stands.

In response, at least some of the ostensibly neutral organizations declare that they are actually against specific injustices and committed to a better society. Nowadays, they often name their positive objective as “social justice” (a phrase whose deepest historical roots are in Catholic thought). In past decades, they might have talked instead about democracy or freedom.

But although some things are obviously unjust, reasonable people disagree profoundly about what constitutes a positive vision of social justice, and why. Thus–I contend–virtually all of the valuable debate that occurred under the aegis of self-described neutral organizations recurs within organizations that declare themselves for “social justice” without providing a detailed definition of that phrase.

The return of debate is not in itself a bad thing; politics is about persistent disagreement, which responsible citizens can embrace and even enjoy. But it is somewhat naive to expect that a commitment to a vague ideal of social justice will bring consensus. And it is a shame if that expectation leads to disillusionment.

In our current time, this is the main pattern I observe: educational, journalistic, and civic associations strongly proclaim neutrality in response to what appears an uncivil and polarized political debate, and then activists demand that they take a stand in response (mainly) to climate change or domestic US racism. Those are matters of grave concern and they have generated social movements that are particularly effective at influencing schools and colleges, the media, and local associations (much more so than governments or corporations). In decades past, opposition to US foreign policy and war played similar roles in challenges to neutrality.

But if there is any doubt that people can be committed to something called “social justice,” abhor the same specific injustices, and yet disagree about the very definition of “justice,” consider the current debates between #BlackLivesMatter and Sen. Sanders, #BlackLivesMatter and Secretary Clinton, or Clinton and Sanders.

Those three people/movements place themselves on the left, but the debate about social justice is certainly broader than that, even if the phrase currently has leftish resonances. In an interview with Eric Liu for a project that Eric and I conducted together, Mark Meckler, who had founded Tea Party Patriots, called the police presence in Ferguson “outrageous.” He acknowledged the salience of racism but mainly viewed police violence as an example of a government depriving individuals of liberty. “The state has a lot of power and only recently it is outwardly manifesting that power in costumes and equipment that demonstrate military might. … That is not of society, by and for society; that is against society.” A democratic socialist might agree with much of that and yet read Ferguson more as a story of disinvestment in industrial cities and the failure of our economy to value workers. I’ve quoted Julius Jones of #BlackLivesMatter as a proponent of a third view: that anti-Black racism is a fundamental chord in American history. Note that all of these positions could simultaneously be true, yet the proponents must disagree about solutions. More government? Less government? Remedies targeted at race? At class? Any of those could constitute “social justice.”

To have a theory of justice, you need principles and a way of ranking or adjudicating among them. Maybe equality is one of your principles, but equality of what? (Opportunity, status, power, welfare?) Equality for whom? (All the students who are already in your classroom or at your college? All major demographic groups within America? All American individuals? All human beings?)

And even if equality–defined in a particular way–is a very high principle for you, what about freedom (which comes in at least six different and incompatible forms), sustainability, security, creativity, innovation, community, rule of law, tradition, diversity, prosperity, and efficiency? A reasonable view of social justice is surely an amalgam of many of these principles, reflecting tradeoffs and rankings. We develop such views in part by reflecting on what is bad about the status quo and what we have learned about practical solutions that work. (For instance, we wouldn’t advocate equality of education if we thought that schools were a waste of time.) Thus a theory of justice typically rests on a narrative about the failures and the successes of our society so far. All of that–the narrative, the assessment of actual institutions, the abstract principles, and their ranking–is contestable.

An organization can claim that it is thoroughly neutral, just a platform for its members to debate what is right. Or it can assert that it is for social justice, and then its members will debate what is right. The difference matters–a bit. A claim of perfect neutrality is inevitably false and distracting. A commitment to social justice can usefully raise the question, “What is justice?”

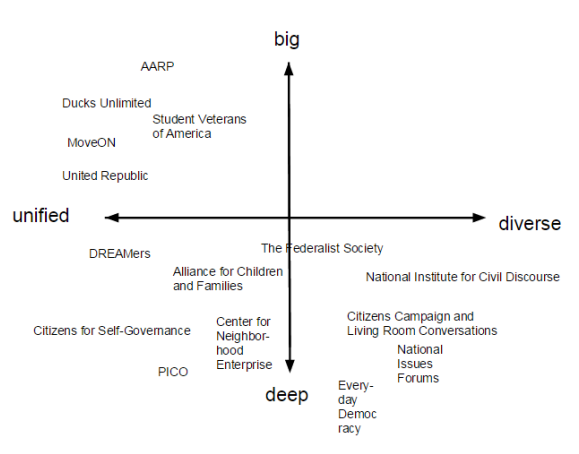

The choice remains how specifically to define the content of social justice. Organizations face choices between ideological diversity and unity and between scale (attracting lots of people) and depth (intensively relating to their members). The more precisely an organization defines its objective, the less hospitable it is to diversity but the more it can achieve unity and advance an agenda. The smaller it is, the better it can work through disagreements, but the bigger it is, the more influence it can have.

I think that organizations that strive to be ideologically diverse and also relatively big are relatively weak and scarce today. Universities and schools and large civic associations can fill that quadrant. It won’t hurt for them to declare themselves for “social justice,” but they would be wise to invite a genuinely diverse debate about what social justice is.