We encourage our members to give some thought to the piece below written by NCDD Supporting Member Matt Leighninger for Public Agenda. In it, Matt reflects on evidence that is beginning to show that democratic innovation can actually decrease social inequality and have many other positive effects, and he proposes a series of critical questions for future research into how we can amplify those benefits. Read Matt’s piece below or find the original here.

To reduce economic inequality, do we need better democracy?

When people have a say in the decisions that affect their lives, they will be better off economically as well as politically.

When people have a say in the decisions that affect their lives, they will be better off economically as well as politically.

This idea has intrigued community development experts, foundation executives, public officials and academic researchers for many years. It has also animated some of the work people and governments are undertaking to address inequality, both in the United States and (especially) in the Global South.

But can a participatory democracy lead to greater economic opportunity? We are just beginning to amass evidence that this idea is true, understand how and why it works, and figure out how to make it happen better and faster.

Over the last two decades we have witnessed a quiet revolution in how governments and other institutions engage the public. Public officials, technologists, engagement practitioners, community organizers and other leaders have developed hundreds of projects, processes, tools and apps that boost engagement.

While they differ in many ways, these strategies and resources have one common thread: they treat citizens like adults rather than the clients (or children) of the state. They give people chances to connect, learn, deliberate, make recommendations, vote on budget or policy decisions, take action to solve public problems or all of the above. The principles behind these practices embody and enable greater political equality.

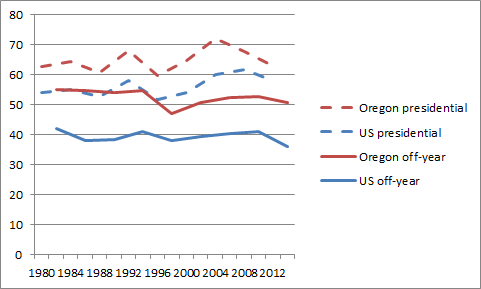

This wave of experimentation has produced inspiring outcomes in cities all over the world, but it has been particularly productive in Brazil and other parts of the Global South, where engagement has been built into the way that many cities operate. In these places, it is increasingly clear that when people have a legitimate voice in the institutions that govern their communities, and when they have support through various kinds of social and political networks, their economic fortunes improve.

The best-documented cases come from cities in Brazil, where Participatory Budgeting and other forms of engagement have been built into a much more robust “civic infrastructure” than we have in most American cities. In other words, people in these places have a wider variety of ways to participate on a broader range of issues and decisions. Their chances for engagement include online opportunities as well as face-to-face meetings. Many are social events as much as political ones: people participate because they get to see their neighbors and feel like they are part of a community, in addition to being able to weigh in on a public decision.

In these cities, the gap between rich and poor has narrowed, much more so than in similar cities without vibrant local democracies. In addition, governments are more likely to complete planned projects; public finances are better managed and less prone to corruption; people exhibit increased trust in public institutions and are more likely to pay their taxes; public expenditures are more likely to benefit low-income people; public health outcomes, such as the rate of infant mortality, have improved; and poverty has been reduced.

The connection between democratic innovation and greater economic equity raises many questions ripe for research:

Does short-term engagement yield long-term impacts?

Most of the engagement work in the United States and other countries of the Global North have come in the form of temporary efforts to address a public issue or policy decision. They have produced outcomes of their own, but due to their short-term nature, they seem unlikely to have shifted long-term challenges like inequality. But this is a hypothesis rather than a well-supported conclusion. We might shed light on this question by assessing the long-term impacts of such processes – for example, projects like Horizons, in which thousands of people in hundreds of small towns in the Pacific Northwest worked together to address rural poverty.

Do stronger networks from sustained engagement boost economic opportunity?

Sustained engagement seems to strengthen community networks, so that people may be more likely to find jobs or find supports that help them work, such as child care or transportation. How much does this “social capital” effect explain the effects of participation on inequality?

What is the role of data and transparency in reducing inequality?

Tiago Peixoto of the World Bank argues that annual participatory budgeting processes make a greater impact on inequality when the data on local inequality are made public, and when local officials and participatory budgeting organizers emphasize those numbers as a key goal of the process. In other words, when people focus regularly on equality data, they are better able to ensure that the process reduces inequality. While participatory budgeting has been proliferating across the United States, the role of inequality data is not as strong in the American processes.

Does engagement in the private sector boost local economies or public-sector engagement?

Workplaces have also used engagement tools and processes to help people learn, connect with colleagues, make decisions and improve how they work. In fact, it may be true that in some cases, private institutions are more responsive and participatory than public ones. In some cases, high levels of engagement in the workplace seem to have spilled over into the community, creating “more robust forms of community engagement.” Some business leaders clearly feel that workplace engagement enhances the productivity of their firms – does it also enhance the state of the local economy? Should we be considering engagement in the private sector as we explore ways to advance it in the public sector?

Is it important to explicitly acknowledge racial and cultural differences in engagement efforts?

Many engagement processes, especially in the United States, have focused on the role of race in public life, especially in areas like policing and immigration. The knowledge gained through engaging citizens around issues of cultural difference helped inform how practitioners organize engagement on other issues. To what extent have engagement efforts in other countries addressed race, and how important is it to explicitly address cultural difference in any attempt to promote participation and reduce inequality?

What can public institutions do to integrate engagement internally and support sustained engagement externally?

How can public institutions, including local governments and K-12 school systems and state and federal institutions such as Congress, incorporate more productive engagement practices and principles in the way they operate? How can these entities work with foundations, universities, businesses, nonprofit organizations and other groups to support more sustained, efficient and powerful opportunities of public participation?

These are ambitious questions. But if we are serious about reducing inequality, at home and abroad, practitioners and researchers should be taking a broader view of what we are learning about democracy and what we might do to improve it.

You can find the original version of this Public Agenda blog post at www.publicagenda.org/blogs/to-reduce-economic-inequality-do-we-need-better-democracy#sthash.RPWmYRS7.dpuf.

![]() Balancing Act is a tool for learning about public budgets and the choices elected officials face in the budgeting process. It allows participants to try allocating funds – expressing their priorities and preferences – but also requires them to balance spending and revenue. Balancing Act brings people and government officials closer together in an informed conversation about what priorities are in everyone’s best interests. Because it is online, it is accessible to anyone at anytime and is far more convenient than a traditional public meeting or budget hearing.

Balancing Act is a tool for learning about public budgets and the choices elected officials face in the budgeting process. It allows participants to try allocating funds – expressing their priorities and preferences – but also requires them to balance spending and revenue. Balancing Act brings people and government officials closer together in an informed conversation about what priorities are in everyone’s best interests. Because it is online, it is accessible to anyone at anytime and is far more convenient than a traditional public meeting or budget hearing.![]()

Tech Tuesdays are a series of learning events focused on technology for engagement. These 1-hour events are designed to help dialogue and deliberation practitioners get a better sense of the online engagement landscape and how they can take advantage of the myriad opportunities available to them. You do not have to be a member of NCDD or IAP2 to participate in this event.

Tech Tuesdays are a series of learning events focused on technology for engagement. These 1-hour events are designed to help dialogue and deliberation practitioners get a better sense of the online engagement landscape and how they can take advantage of the myriad opportunities available to them. You do not have to be a member of NCDD or IAP2 to participate in this event.