We recently started reading a terrific interview series from the talented team at Collaborative Services on public participation lessons they have learned in the last year, and we wanted to share their insights with the NCDD community. The first interview in the series features the reflections of NCDD supporting member Amy Lenzo of the World Café - an organization whose founders are also NCDD founding members. You can read the interview below, or find the original on Collaborative Services’ blog by clicking here.

The World Café: We Are Wiser Together

You may have heard the saying “If you’re not at the table, you’re probably on the menu.” Meaning if you aren’t actively participating, then you’re probably the topic being discussed or getting ready to be figuratively eaten. All the more reason to pull up a seat and actively engage in the discussions that matter to you.

Participating in large groups can be difficult, but one organization has developed a unique approach to make it easier for people just like you to be at the table for important civic discussions.

This week we start our series on successful public participation hearing from Amy Lenzo, the Director of World Café Learning Programs. The inspiration for the World Café came from a gathering of twenty academic and corporate leaders one rainy day at the home of World Café founders, Juanita Brown and David Isaacs. Since the rain prevented the group from starting their day on the patio, Brown and Isaacs set up make-shift café tables in their living room using TV tables fit with white easel paper as table cloths and vases with flowers as an alternative setting for their guests to gather for coffee and breakfast upon their arrival for their second day of key strategic dialogue on the field of Intellectual Capital.

Soon, and without any prompting, Brown and Isaacs noticed the small groups becoming deeply engaged in conversation and writing their thoughts and comments on the paper table cloths. Forty-five minutes later the suggestion was made for one host from each small group to stay at their table and for the rest of the members to move to different tables as a way for everyone to learn what had come out of the conversations happening in the other groups. From there the room was alive, the guests were excited and engaged, and the World Café method was born.

The World Café method emphasizes the importance of creating a comfortable environment to draw people in. Just as with Brown and Isaacs’ group of academic and corporate leaders, small round tables with checkered tablecloths and vases with flowers help create the feeling of being at a café and make participating feel as easy as conversing over a cup of coffee with friends. Having a hospitable and inviting environment is important, especially when discussions have the potential to get heated.

The World Café method has resonated with cultures around the world, helping to establish a global common ground for public participation. This week we will learn more about the World Café’s global community and its method and process for successful public participation.

- — -

How is the World Café approach different from traditional approaches to public engagement efforts?

The World Café is based on the premise that we are wiser together than any of us are alone, so it’s all about participation, and welcoming diversity so that we can learn from each other. It’s not a “top-down” communication process – each voice is valued equally and the focus is on sensing the “collective wisdom” that can exist between us when we really listen to each other and pay attention to the patterns that emerge within our conversations.

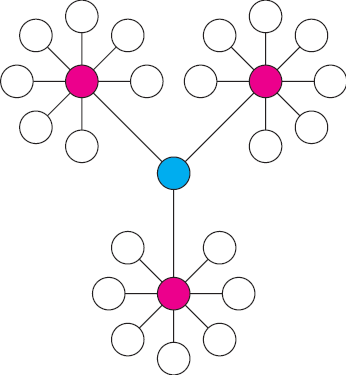

Another unique characteristic of the World Café process is its capacity for both intimacy and scale.

World Cafes can engage very large numbers of people – They have been done successfully with many thousands of people – without losing the sense of intimacy and depth that 20-minute table conversations with no more than 4 people at a table can foster. It’s amazing how deep these table conversations can be even among strangers, while the rotating rounds of conversation & whole group harvest give participants an experience of the larger picture.

Credit: The World Café Flickr

Is there an ideal use of the World Café approach or can it be applied to all public gatherings?

Well, there are situations where the World Café is not the best approach – when the group is less than 12 people, say, or when the result of the conversation is already known, e.g. when you just want to get information across. But when you have more than 12 people and there is respect for the innate capacity of people to address what is most important to them, the World Café can work well for any event, be it community-based and public or private including corporate, organizational, and institutional.

The World Café is based on seven design principles. How were these principles developed?

The World Café process itself happened spontaneously in response to particular circumstances during an international gathering of Intellectual Capital pioneers at Juanita Brown’s home. Subsequently, when it was clear that something extraordinary had happened that day, Juanita and colleagues Finn Voltoft and David Isaacs, with help from many others, embarked upon a serious investigation to find out exactly what conditions led to the experience and research whether or not the experience could be replicated. The result of this research gave rise to the formulation of the seven World Café design principles, which form the basis for World Café practice.

Is one or some of the principles more integral to fostering meaningful conversations? Or do they all play an equal part?

Every World Café design principle is a key element within the set. They can be used individually as powerful aids to meaningful conversation, and there are many synergies among them, but when the seven design principles are utilized in concert together they create the conditions whereby something truly extraordinary can occur.

Tell us more about the World Café online community. When did this start and how has it evolved over the years?

The international network of people using the World Café has grown exponentially ever since the World Café method was introduced. This growth was organic – largely through experience or word of mouth – and steady. Within a few years there were more than a thousand people engaging in conversation about their experiences hosting or participating in World Café. At that point, the World Café Community Foundation commissioned the first online community platform to support these conversations within what we have come to call a “community of practice.”

Credit: World Café

Online platforms have changed and been re-designed, but the number of people in the World Café online community continues to grow. There are currently almost 4,500 members from every continent, and almost every country in the World Café online community platform and over 2,000 in a Linkedin group. In addition, people all over the world share their World Café photos on Flickr and participate in a variety of other social media conversations online.

The actual number of practitioners and those who have experienced a World Café is of course many, many times higher. And now, as our online learning programs expand (we’re launching a new Masters Level course in World Café and Appreciative Inquiry with Fielding Graduate University in the Fall 2014 term), the numbers of actively engaged new practitioners continue to grow exponentially.

You’ve coined the term “conversational leader.” Can you explain the responsibilities of a conversational leader and what processes they should follow to successfully engage their participants?

We didn’t coin the term – World Café host Carolyn Baldwin did – but we have continued to evolve and develop the idea. Juanita Brown and Tom Hurley wrote a wonderful article on this subject, which is available as a free download on our website. Basically, the idea is that conversational leaders recognize conversation as a core meaning-making process and consciously create opportunities for meaningful conversation to occur in their organizations, as well as fruitfully utilize the results of those conversations.

The World Café approach is used by organizations and educational institutions around the world. What are some of the best examples of this approach in action that you have seen?

There are so many! We have an impact map on the World Café website with some great examples but I think one of the most striking was a World Café hosted in Tel Aviv. It was a reasonably ambitious event from the beginning – planned and set up as an outdoor World Café to engage up to 4,000 Israelis in a political and social conversation about transforming their country for the better – but according to reports from the hosts and other media, over 10,000 people showed up!

Why do you think this approach resonates with so many different cultures?

Conversation is a core human activity. We all do it; it’s fundamental to our nature, whatever our culture. We all crave the opportunity to be heard as we speak to others about things that really matter to us, and it is always moving to hear what really matters to others. Being part of a World Café conversation where there is a truly diverse set of participants – all of whom are welcomed and their perspectives valued – can be a life-changing experience.

An example of graphic recording from the Reno Climate Change Café.

(Credit: The World Café Flickr)

Graphic recording (capturing people’s idea’s and expressions in words, images and color – as they are being spoken) is recommended as part of the World Café approach. While recording the input received is a valuable practice, and many times a requirement for most public engagement opportunities, how does graphic recording benefit the participant?

From my perspective it’s the participant that gains most of all by having a graphic listener/recorder present as part of the World Café hosting team! Professional graphic facilitators are trained in ways that make them very valuable in capturing the essence of what is being shared during the harvesting process, but they are also invaluable collaborators for things like finding the right questions to help participants cut to the heart of the issue. During the harvest, having their words and ideas faithfully reflected is very powerful for the participant who has shared them, and seeing the collective meaning literally take form in front of the group is very valuable for the whole group – a fabulous fulfillment of the 7th World Café principle to “share collective discoveries.”

Which strategies could our readers take with them to help them become better communicators?

I think the main skill we can all develop in becoming better communicators is that of deep listening. And by deep listening I mean not just listening to understand another person’s point of view, although that can be very valuable in and of itself, but listening for what we can learn from the differences in perspective we hear. In other words, stepping outside of our own opinion in order to listen and learn from diverse points of view. That skill or strategy alone could not only make us better communicators, but it might even change the world for the better.

- — -

Thank you Amy for sharing your insights and for working to change the world for the better.

This interview is part of a blog series from Collaborative Services, Inc. - a public outreach firm in San Diego, California that brings people together from their individual spheres and disciplines to improve communities and help people adapt to an ever-changing world. The firm uses inter-disciplinary efforts to manage and provide services in stakeholder involvement, marketing and communications, and public affairs. The firm’s award-winning services have spanned the western region of the United States from Tacoma, Washington to the Mexico Port of Entry.

We thank Collaborative Services for allowing NCDD to learn along with them, and we encourage our members to visit their blog by clicking here. You can find the original version of the above article at www.collaborativeservicesinc.wordpress.com/2014/01/16/the-world-cafe-we-are-wiser-together.