A human is a spidery thing: digits, Appendages for sensing the currents, Good for catching, clutching, striking, stroking; An upright anemone, an antenna. A dog is a nose-delivery system, Built for forward motion with detours: A face on propulsive feet, a torpedo (Until sacked-out, done for now, recharging). Joined by the filament of a leash that Ties me to him as much as him to me, We loop through a net of scents, sounds, memories, Tugged back to the door that keeps us both safe.

NCDD Member Discount Available on TPC’s IAP2 Trainings

Now is a great time to strengthen your D&D skills and knowledge, which is why we are excited to announce the upcoming training schedule for NCDD member org, The Participation Company. TPC offers certification in the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2)‘s model, and dues-paying NCDD members get a discount on registration! You can read more about the trainings in the TCP announcement below and learn more here.

The Participation Company’s 2020-2021 Training Events

Completely revamped in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, TPC is pleased to announce that we are ready to offer on-line courses:

Completely revamped in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, TPC is pleased to announce that we are ready to offer on-line courses:

The International Association for Public Participation’s flagship Foundations Program. Module One introduces a proven method for planning effective public participation and Module Two equips students with 40+ diverse methods for accomplishing engagement objectives. Both courses are delivered in half-day sessions full of interactive exercises and opportunities to get to work with your fellow students virtually. Class size, as always, is limited to 25 students to provide the maximum opportunity to learn.

IAP2’s Foundations in Public Participation (9- 4 hour on-line sessions) Certificate Program:

- Planning for Effective Public Participation (5- 4 hour on-line sessions)

- Techniques for Effective Public Participation (4- 4 hour on-line sessions)*

*The Planning module is a prerequisite to Techniques module

- PLANNING SEP 28 – OCT 2; TECHNIQUES OCT 5 – 8

- PLANNING NOV 2 – 6; TECHNIQUES NOV 9 – 12

- PLANNING NOV 30 – DEC 4; TECHNIQUES DEC 7 – 10

- PLANNING JAN 25 – 29; TECHNIQUES FEB 1 – 4

- PLANNING FEB 22 – 26; TECHNIQUES MAR 1 – 4

- PLANNING APR 12 – 16; TECHNIQUES APR 19 – 22

- PLANNING MAY 10 – 14; TECHNIQUES MAY 17 – 20

The International Association for Public Participation’s Strategies for Dealing with Opposition and Outrage in Public Participation. This four (4)- 3 hour on-line sessions of conflict resolution training workshop builds on IAP2’s global best practices in public involvement and the work of Dr. Peter Sandman, offered in partnership with the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2).

IAP2’s Strategies for Dealing with Opposition and Outrage in Public Participation (4- 3.0 hour on-line sessions)

- STRATEGIES NOV 16 -19

The Participation Company’s new course on Building Public Trust in Government

This two (2)- 3.0 hour on-line workshop will help you and your team (re)build trust with oftentimes cynical, skeptical and oppositional citizens. Attendees will better understand and manage interactions with highly suspicious and skeptical citizens who don’t believe in government authority or the value of public service professionals. Learn more about the course or choose your date below:

TPC’s Building Public Trust in Government:

- BUILD TRUST OCT 20 – 21

For more detailed information: https://theparticipationcompany.com/training/

The Participation Company (TPC) offers discounted rates to members of AICP, ICMA, IAP2, and NCDD.

AICP members can earn Certification Maintenance (CM) credits for these courses.

discrimination boosts civic engagement

My colleagues Debbie Schildkraut and Jayanthi Mistry have published a new research brief on the Tufts Equity Research page. They find that people who feel they have experienced discrimination are more likely to be involved in civic activities like canvassing and contributing money to causes. People who have been discriminated against are also more confident in their ability to address community problems.

For example,

As figure 4 shows, as the frequency of perceived discrimination in the past 12 months increases, the likelihood of having worked with others informally to solve a community problem increases substantially. While a white or Hispanic person who has never experienced discrimination the past 12 months has only a 25% chance of this type of collaboration, a white or Hispanic person who experienced all types of discrimination frequently has a 72% chance. Black respondents show an equally impressive increase in engagement (19% to 63%)

Viewing one’s own racial or ethnic identity as important does not boost civic engagement. Neither does thinking that being American is important. However, “When people are prompted to think specifically about their relationship to a larger group and its potential power, their racial identity and American identity matter more than perceptions of discrimination in promoting civic engagement.”

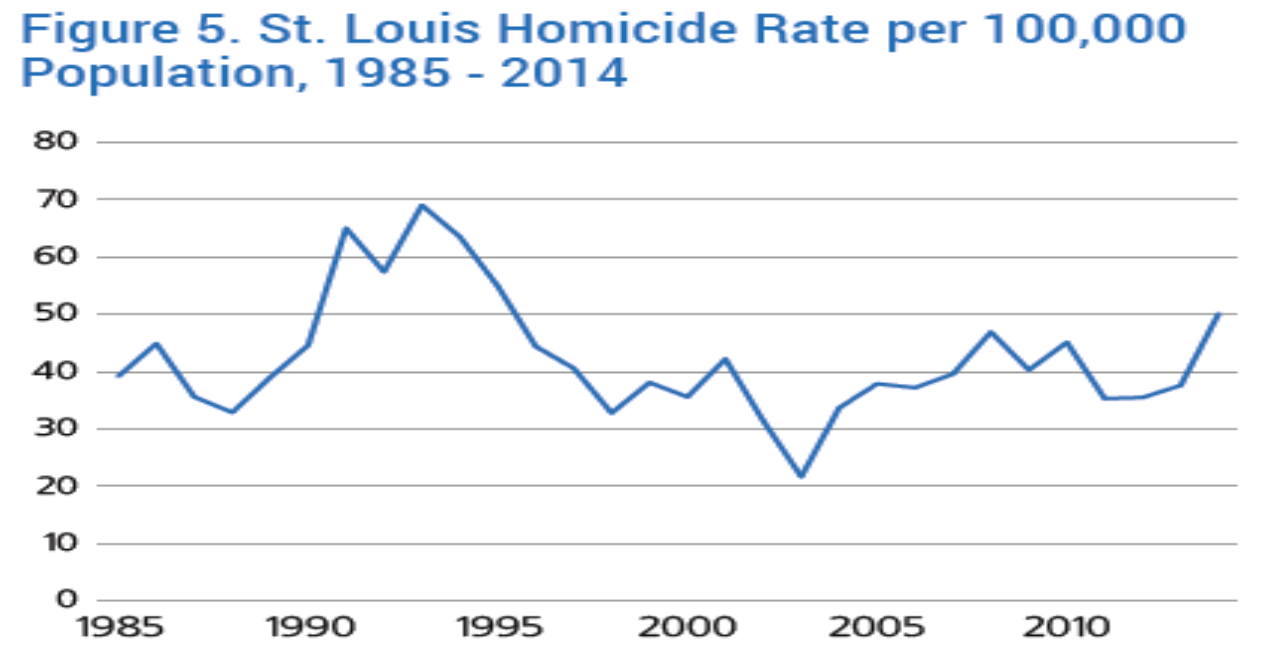

Is Deliberate Underpolicing a Problem?

Propublica thinks so: What Can Mayors Do When the Police Stop Doing Their Jobs?

Rises and falls in crime rates are notoriously hard to explain definitively. Scholars still don’t agree on the causes of a decades long nationwide decline in crime. Still, some academics who have studied the phenomenon in recent years see evidence that rising rates of violence in cities that have experienced high-profile incidents of police brutality are driven by police pullbacks. Many criminologists also cite the general deterioration of trust between the community and police, which leaves residents less likely to report crimes, call in tips or testify in court. Added to that are the dynamics that are now likely also driving a rise in violent crime, even in cities that have not witnessed recent high-profile deaths at police hands: the economic and social stresses of the pandemic lockdowns, including disruptions to illegal drug markets, and the usual seasonal rise in violence during summer.

I tend to discount the so-called “Ferguson Effect,” because the overall crime rates are already so noisy, and Michael Brown was killed while there was already a rising crime rate.

ProPublica acknowledge this evidence, but then cites anecdotes from Baltimore to raise the problem anew:

But the post-consent-decree pullback did not result in a rise in violent crime in the city, whose homicide rate remained very low compared with other large cities. In this, the city is representative of a broader trend, according to two recent de-policing studies. Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri at St. Louis, and Joel Wallman, the director of research for the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, examined the impact of arrest rates in 53 large cities on homicide rates from 2010 to 2015. They found that arrests, especially for less serious crimes such as loitering, public intoxication, drug possession and vagrancy, had already been dropping over that period, even prior to the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014. And they found that in nearly all of those cities, the declining arrest rates did not result in higher rates of violence. To put it another way: Over the first half of the past decade, many cities shifted away from the “broken windows” style of policing popularized in New York under former Mayor Rudy Giuliani, but even as they did so, violent crime continued to decline in most places, as it has since the early 1990s.

Here are the anecdotes about Baltimore:

In Baltimore in 2015, the underpolicing was so conspicuous that even some community activists who had long pushed for more restrained policing were left desperate as violence rose in their neighborhoods. “We saw a pullback in this community for over a month where it was up to the community to police the community. And quite frankly, we were outgunned,” the West Baltimore community organizer Ray Kelly told me in 2018. In fact, the violence got so out of hand — a 62% increase in homicides over the year before — that even some street-level drug dealers were pleading for greater police presence: One police commander, Melvin Russell, told New York magazine in 2015 that he’d been approached by a drug dealer in the same area where Gray had been arrested, who asked him to send a message back to the police commissioner. “We know they still mad at us,” the dealer said. “We pissed at them. But we need our police.”

I think there’s good reason to be skeptical (beyond the self-serving motivated reasoning inherent in a police commander’s report of a drug dealer’s plea): aggregate crime levels are a noisy phenomenon, and they’re unusually responsive to the agencies that are charged both with monitoring them and lowering them. We know precincts in NYC would “juke the stats” and we also know that a lot of crime is inexplicably random, or tied to the efforts of third parties. So if there are two cities where police pullback was associated with subsequnce increases in violent crime, and hundreds of cities where it wasn’t, it looks irresponsible of ProPublica to write this article, even if it’s ultimately a sympathetic one.

There’s some historical justification for this view, as well:

The Week Without Police: What We Can Learn from the 1971 NYC Police Strike

Over the course of the five day strike, there was no apparent increase in crime throughout the city. In fact, the only real differences noted by reporters were an increase in illegally parked cars and people running red lights, the actions of opportunistic motorists. Richard Reeves, writing for the New York Times, said “New Yorkers— ‘a special breed of cats’…went about their heads‐down business. There was no crime wave, no massive traffic jams, no rioting.” Some attributed all of this to Police Commissioner Patrick V. Murphy’s “visible presence” strategy of deploying superior officers and detectives in patrol cars in heavily populated areas, like Times Square. Others simply attributed it to the cold. However, the strike brought to light another very real possibility: maybe the city was able to function as normal with a much smaller number of police officers.

In New York, major crime complaints fell when cops took a break from ‘proactive policing’

Each week during the slowdown saw civilians report an estimated 43 fewer felony assaults, 40 fewer burglaries and 40 fewer acts of grand larceny. And this slight suppression of major crime rates actually continued for seven to 14 weeks after those drops in proactive policing — which led the researchers to estimate that overall, the slowdown resulted in about 2,100 fewer major-crimes complaints.

Here’s the underlying 2017 study. (Here’s where I predicted these results in 2014.)

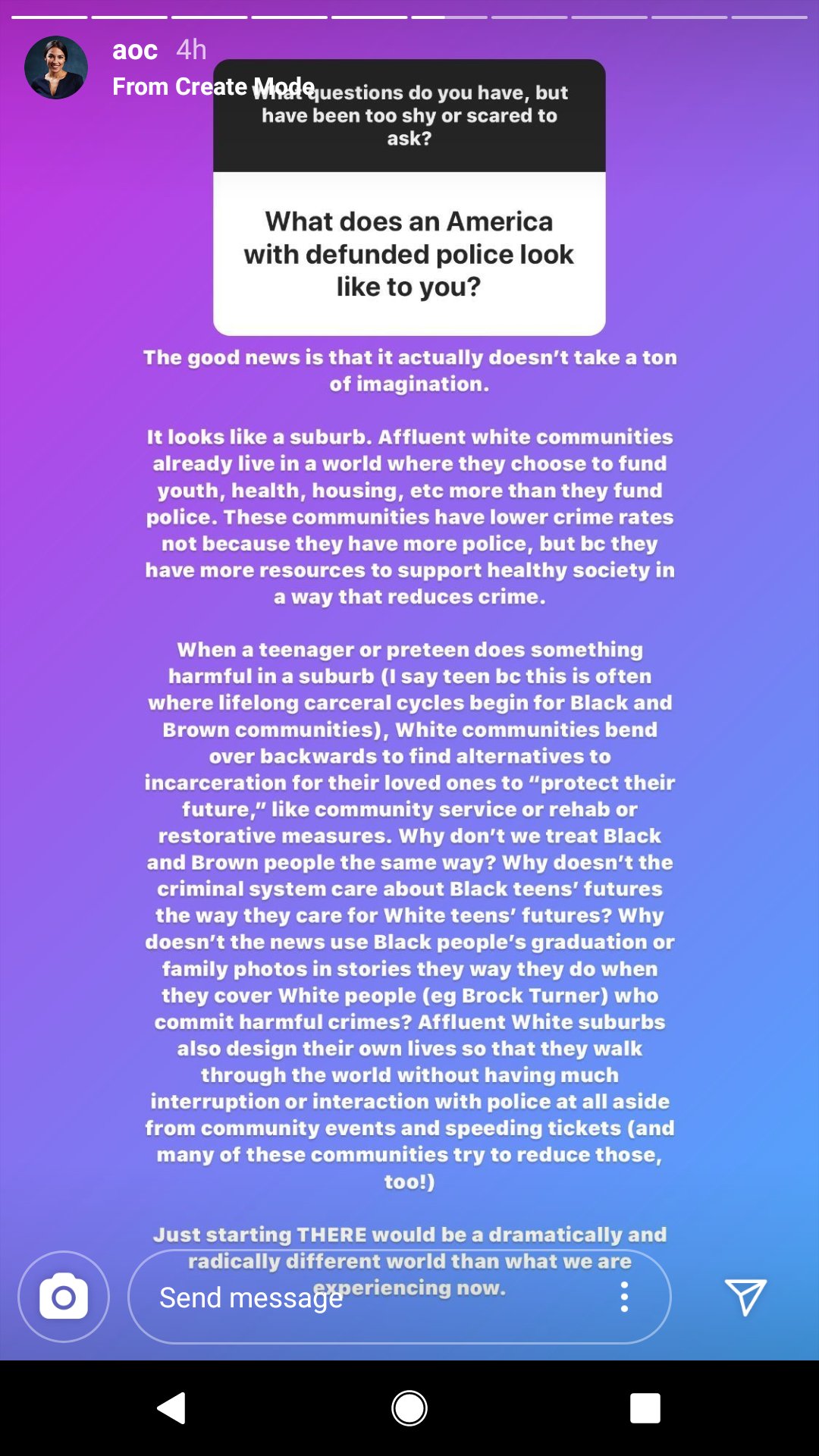

At the same time, the version of policing reform that’s most commonly endorsed by leftist politicians like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is one where the simultaneous over- and under-policing of African-American communities is understood to be part of the same phenomenon, and corrected together such that Black Americans finally receive the same treatment as middle-class whites.

If the ideal of policing abolitionists is that we should all have responsive, service-oriented police, then a very good way to get there would be community control boards. My colleague Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò has argued that this could just as easily be abolitionist as reformist:

By taking public control over the police who handle the bulk of arrests, we act before other parts of the system can get involved. Without community control, abolition just means asking a larger set of white supremacist institutions to restructure a smaller set. Instead, we are asking our neighbors.

where have we already seen second waves of COVID-19?

I’m definitely not an epidemiologist, so take this post with thousands of grains of salt. But I am trying to think about whether we should expect a major second wave of COVID-19.

Andrew Atkeson, Karen Kopecky, Tao Zha look at the 23 countries and 25 states with the highest death tolls and find a consistent pattern for all of them. One clear peak has been followed by “relatively slow growth or even shrinkage of daily deaths from the disease.” These are illustrations of the classic pattern:

There is enormous variation in the death rate at the peak. For instance, at their respective peaks, 24 people per million died each day in Belgium, versus 0.27 per million in New Zealand. Yet most states and countries–and all the ones included by Atkeson, Kopecky, and Zha–look similar 20-30 days after the peak. Belgium, for example, has had less than one daily death per million since June 12.

However, some countries and states do not exhibit this pattern. I have found pretty clear evidence of second peaks in Croatia, Iran, Israel, Japan, and Turkey, plus Idaho, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

I included the USA in the graph because it also shows two humps (the second smaller than the first). However, disaggregating US data to the state level suggests that there were simply two batches of states that had one peak each. At the state level, the only true second peaks that I see are in Idaho, Louisiana, and Mississippi. There are also some cases, like Australia, in which you can see a second peak if you squint–but the death rate has never been high. And there are countries, like Ukraine, that seem to wobble upward slowly without peaking,

Reading Atkeson, Kopecky, and Zha, one might guess that most badly-afflicted countries have accomplished impressive declines by implementing interventions. That is not such good news, since these policies are costly and hard to sustain. But it would be surprising if all the jurisdictions in their sample accomplished the same outcome in 20-30 days despite applying divergent policies. There is some chatter that these places have reached herd immunity, but I am convinced by Howard Forman and others that’s not what’s happening. Still there could be a strong tendency for COVID-19 to taper off for other reasons, which might offer good news.

It could also be the case that we simply haven’t seen many second waves yet. When you play Russian Roulette, things often go fine for a while, but the game always ends the same. Possibly places like Turkey and Croatia and Idaho and Louisiana demonstrate that we’re all at risk of a resurgence at a random moment.

Some European countries have recently reported increases in cases, although not deaths. Perhaps this is only because of increased testing rates–but then again, why is testing becoming more common unless rising numbers of people are experiencing symptoms? Deaths may follow.

In any event, I am searching and waiting for more information about the actual second waves. Why have they happened and what can we learn from their experiences?

Some EXCELLENT Free or Low Cost Professional Developments for Civics and Government!

Are you looking for some useful virtual professional development that can help you teach about elections and prepare for Constitution Day? Be sure to check out these excellent PDs being offered by some excellent providers! Thanks to the inestimable Mary Ellen Daneels for giving a heads up about these.

This virtual conference is provided by the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and man, it looks FANTASTIC!

TEACHING ABOUT THE 2020 ELECTIONS

Teaching about elections is one of the best opportunities to prepare young people for political engagement. This conference helps educators teach about electoral politics in a way that is engaging, respectful to all points of view, and supported by the best and most current information.

WHAT TO EXPECT

The Teaching About the 2020 Elections Conference is an exciting opportunity for K-12 teachers and administrators to:

- Learn about important election-related issues

- Access resources that support instruction and enhance student learning

- Be introduced to national civic education programs and their curricula

Politics can be divisive, confusing, and challenging to approach. This conference will help educators find ways to ensure their students can discuss these sensitive and important topics with care, knowledge, and facts.

PROGRAM DETAILS

When: September 26, 2020, 9:00 a.m.–2:45 p.m. CDT

Where: Online

AND CHECK OUT THE LINEUP OF ALL STARS!

Check out the page for more information. It’s only ten dollars!

Another great opportunity comes to us around a book, Faultlines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws that Affect Us Today, by Cynthia and Sanford Levinson

Join co-authors Cynthia and Sanford Levinson in a conversation with moderator Mary Ellen Daneels about FAULT LINES IN THE CONSTITUTION to help prepare for Constitution Day lessons this year!

They’ll be discussing today’s most timely and urgent topics, including the Presidential election, Coronavirus, protests, and more — all as they relate to the Constitution.

This virtual conversation will

You can learn more about this event here! And, good news for teachers, the book has a graphic novel edition coming out.

Civics in Real Life: Labor Day

The newest Civics in Real Life is now available! We take a break from our election series to share a look at Labor Day, and how it reflects civic engagement and civic life!

Meanwhile, as a reminder, our election season series continues as we explore national party conventions and the role that they play in presidential elections.

Presidential Nominating Conventions

Another new one in our election series explores voter registration. Did you know that every state has different expectations for voter registration, and some communities even let non-citizens and 16 year olds vote in local elections?

Voter Registration

As a reminder, so far our topics this fall have explored

Elections

Voting Rights

Voting Rights

These will be updated once a week throughout the school year, addressing or relating to current events and civic concepts, without necessarily directly connecting to any particular state standards and benchmarks. We hope you find these one page resources useful!

You can find an overview of the ones from spring here! These are all still available over on Florida Citizen.

taxing and spending are more compatible with democratic values than regulation is

Democratic governments can choose what and how much to tax and how to spend the resulting revenue without undermining essential aspects of good governance: accountability, representativeness, rule of law, transparency, public deliberation, and the ability to learn from experience. In fact, better governance tends to accompany higher government spending.

Regulation is more difficult to square with democratic values and other aspects of good governance. Complex regulatory systems create tensions with democracy and other political values, which I briefly explore below.

This is why I am hopeful about proposals like the Green New Deal, which promise to address profound crises by taxing and spending. Insofar as we must also address the climate crisis by regulating (which may be necessary), we’ll face more difficult tradeoffs between ends and means–between essential environmental outcomes and improving our politics.

In any republic, whether a true democracy or not, we must know who the decision-makers are and what they do in order to hold them accountable. We must be able to predict the consequences of their actions to plan our own behavior, thus gaining a reasonable level of control and responsibility.

These two principles imply that state decisions should be made by finite groups of clearly identified actors, e.g., the 535 Members of Congress and the President, acting on the record. Their policies should be as clear, uncomplicated, and durable as possible. As Madison writes in Federalist 62:

The internal effects of a mutable policy are … calamitous. It poisons the blessings of liberty itself. It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood: if they be repealed or revised before they are promulg[at]ed, or undergo such incessant changes, that no man who knows what the law is to-day, can guess what it will be to-morrow.

Taxation is compatible with these principles. A tax usually requires a recorded vote in Congress and the president’s signature, so we know who enacted it. Although there can be some ambiguity and unpredictability about who ultimately pays–companies try to pass their taxes on to consumers–you often know if you are paying a tax. You can decide if you think it’s worth it.

Regulation can also be compatible with these principles. If Congress banned automatic weapons, that would be a clear regulation for which representatives could be held accountable. No one can be sure of its downstream consequences, such as its effects on the homicide rate. But the direct effect is very clear: companies must stop selling automatic weapons to consumers.

However, regulations often violate these principles. In a complex society, regulations that are designed to maximize outcomes (such as safety or efficiency) will be complicated, and they will have to change frequently to keep pace with changes in society. Congress cannot write such regulations. It is composed of too few people with too little time and expertise. Congress almost inevitably delegates its regulatory power to regulators. Those people are often dedicated, underpaid civil servants. Yet they are anonymous and numerous, and they have interests and biases that are hard to know, let alone control. They can write regulations to benefit incumbent companies and industries and to discourage competition. Special interests can capture the regulatory process. Meanwhile, Congress has every incentive to take credit for the declared intentions of a law while delegating the tough choices to regulators, thus dodging responsibility. A particularly common move is to pass a law that requires incompatible outcomes–like safety and economic efficiency–and then complain about the actual regulations.

To be sure, taxes can also be designed in ways that are complex, mutable, opaque, and biased in favor of incumbent interests. The federal tax code is 2,600 pages long, with too many exemptions and loopholes. However, the Code of Federal Regulations is 186,374 pages long, or 72 times as long. Several times as many pages are added to the CFR each year (including under Trump) than comprise the entire tax code.

Big differences in quantity (like a 72-to-one ratio in page numbers) can turn into qualitative differences. Taxing and spending are more transparent and predictable than regulation.

I vote for parties and candidates who are relatively favorable to both regulation and taxing-and-spending. Often those interventions promote equity and the public good. I understand them as components of a mixed or pluralist political economy, which is the kind I support.

Nevertheless, it is always important to consider the costs and risks of good things. For the drawbacks of taxation and regulation, it’s worth reading or rereading classical liberals/libertarians and public choice theorists. I believe they offer stronger arguments against regulation than against taxation. Their concerns are especially relevant when the regulatory state lacks both legitimacy and actual capacity. Then the odds are low that agencies will achieve clear victories as they address complex public problems. Their impact is likely to be ambiguous and contested, at best. Under these circumstances, it is much more promising to raise revenues and purchase solutions that all can see.

See also: on government versus governance, or the rule of law versus pragmatism; on the Deep State, the administrative state, and the civil service; The truth in Hayek; how a mixed economy shapes our mentalities; China teaches the value of political pluralism; better governments tend to be bigger; A Civic Green New Deal; and the Green New Deal and civic renewal.

Medialab Prado: Applying the Open Source Ethic to Civic Innovation

Improbable as it seems, there is actually a vibrant citizens’ research and development lab for innovation in civic life and culture. It has its own building, funding from the city of Madrid, and robust participation from activists, academics, techies, artists, policy experts and ordinary citizens.

Welcome to Medialab Prado in Madrid, Spain. It’s a very special institution that explores new forms of commoning on various tech platforms and systems. Billing itself as a “collective intelligence laboratory for democratic participation,” the lab pursues a wide-ranging agenda of R&D with great brio. In this moment of great danger to democracy, I find it inspiring that a serious, progressive-minded institution is boldly prowling the frontiers of experimental practice.

To showcase some of the amazing work that Medialab Prado does, I interviewed Marcos García, the lab’s artistic director, for Episode #7 of my podcast Frontiers of Commoning. Marcos is a wonderfully gracious fellow who exudes a reassuring calm despite a formidable responsibility in overseeing many ambitious, speculative projects. Let me offer a brief, incomplete tour.

An open data project is exploring new ways to use shareable databases in creative, public-spirited ways. The “Follow the Food” workshop, for example, investigated how to tell data-driven stories through journalism. It developed data visualizations about the food system so that people can better understand where their food comes from, and how and why that systems works the way it does.

The “Eating Against Collapse” project is trying to imagine scenarios that can get us beyond the current, unsustainable agro-industrial food model. Organizers solicited proposals for new models of agricultural production and distribution, and then ran a prototyping workshop for two weeks, along with an international seminar on the work, a public presentation of the prototypes, and an exhibition of them.

Medialab Prado also hosts a citizen-science lab to “help make scientific research more democratic and transversal, ensuring it encompasses a range of perspectives.” Its DITOs project – “Doing It Together” -- is a pan-European network aimed at fostering citizen participation in environmental sustainability and biodesign.

The accent of so much of Medialab Prado’s work is open participation and exploration. How can we develop innovative ways of meeting civic needs? A participatory budgeting project, for example, focuses on empowering citizens to make their own choices in allocating local government budgets.

A recent “Taxi Experiment” brought together cab drivers with their families, users, and community members to explore how the experience of riding in a taxi could be improved. Drivers learned more about the needs of riders with disabilities, for example, and an app was designed to improve the service that cabs could offer.

Now Medialab Prado is trying to go global with its civic incubation model. In September and October, it will be hosting a MOOC course (in Spanish) on “how to grow your own citizen laboratory and build networks of cooperation.” The idea is to foster very localized citizen innovation labs, even in rural areas, by helping people learn how to host prototyping workshops, use helpful digital tools, issue open calls to identify projects and collaborators, and run communication plans, mediation, documentation, evaluation, etc.

The lab hopes that this effort will result in an international collective of distributed citizen laboratories. An English version of the course may be offered in 2021. More about it here.

A recurrent theme of Medialab Prado projects is to serve as “a listening tool to see what people want,” as García puts it. “We provide a neutral, comfortable space for people that is useful at the municipal level,” said García. When people are invited to participate, share what’s on their minds, and are given tools to self-organize in a welcoming, supportive environment, some remarkable new ideas emerge. The process amounts to applying the open source ethic to civic contexts.

Medialab Prado is helping citizens and society evolve together in more thoughtful ways. “A big question we should always be asking ourselves,” said García, “is how we want to be living together. In a way, the prototypes that people are making [at the Medialab] have to do with that question.”

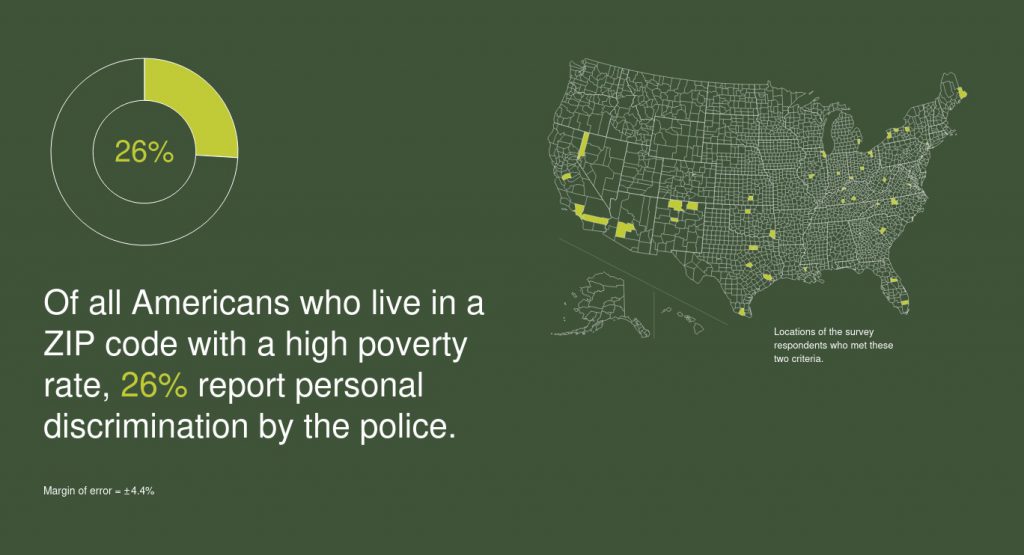

police discrimination, race, and community poverty

Our new Equity in America website shows that more than a quarter of Americans who live in high-poverty ZIP codes report having been personally mistreated by the police. That is 10 points higher than the rate in high-income communities.

Zooming in on the map shows that many of the people in our survey who live in high-poverty ZIP codes and who reported police discrimination reside in smaller cities or towns. Chicago, Miami, Queens (NY) and Los Angeles each supply one person in our survey who met these criteria, but so does my hometown of Syracuse, NY, Aurora, CO, and Spokane, WA, for example.

So I formed the hypothesis that living in a low-income, smaller community might be a risk factor for police discrimination. I tested that hypothesis with a binomial logistic regression, treating being discriminated against by the police as a yes-or-no matter. This is a similar method that might be used to predict being hired for a job or getting a disease. These issues are very different morally, but we can use the same math.

For possible predictors, I considered race, gender, education, age, English-language proficiency, household income, housing type, county-level income (not self-reported, but from Census data), and any mental health diagnosis.

It should not surprise anyone that being African American is the major risk factor. If we include any police discrimination, being Black raises the odds of being mistreated by the police almost five-fold (4.6 times), and that result is statistically significant at any level. If you exclude discrimination that happened far in the past, being Black still raises the odds threefold (2.955 times).

Identifying as female cuts your odds in half or better. More education helps, to a statistically significant yet modest degree. (This implies that highly educated African Americans have almost the same risk as those with little schooling.) The risk declines with age, but that pattern just misses being statistically significant, as does the risk from being Latino. Having a low family income, not speaking English well, reporting mental health issues, and living in an apartment rather than a house are not significant predictors. Neither is living in a poor ZIP code or a town or rural area as opposed to a city.

In short, my hypothesis about community factors was not correct–the race and gender of the individual is what matters. However, it remains true that a lot of police discrimination occurs in smaller, low-income communities, and that has implications for how we should address this grievous problem.

See also: Two-thirds of African Americans know someone mistreated by police, and 22% report mistreatment in past year; more data on police interactions by race; insights on police reform from Elinor Ostrom and social choice theory; and explore the dimensions of equity and inequity in the USA.