We are having a passionate, complex, deeply informed discussion about race in America and related topics, such as policing.

If you believe that a deliberative democracy means one conversation that convenes representatives of all perspectives, who decide, without rancor and recrimination, what they should do next as a unified group, then the current discussion misses the standard. But I never had that ideal in mind. I always assumed that a national deliberation would result from demands and critiques and would unfold in many settings. I always assumed it would be impassioned and challenging.

In the current debate, some prominent people can be interpreted as wanting to silence their opponents. When Barack Obama called “defund the police” a “snappy slogan” that “lost a big audience,” that sounded like advice to drop the slogan. On the other hand, to equate opposition to defunding police with white supremacy could also be interpreted as silencing.

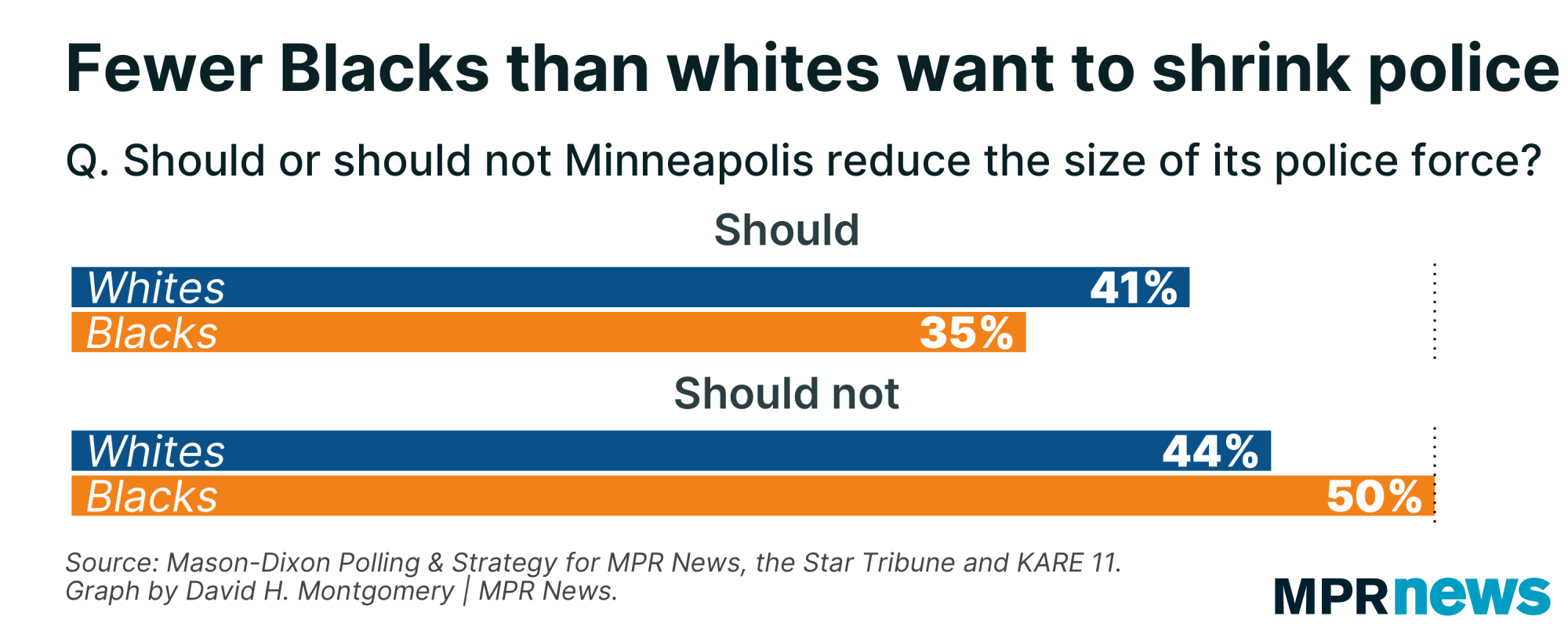

These statements do not worry me much, because they will not actually silence anyone. They are acts of free speech, not restrictions on it. And, by the way, they are probably both true. If we defeated white supremacy, we would not have to consider defunding police. Yet defunding police polls badly among constituencies that should matter, like Black people in the Twin Cities:

Although Barack Obama may not be the best messenger for a certain kind of pragmatic meliorism, telling him not to say what he thinks is just as silencing as his own statement might be. The conversation should continue–and it will. It’s not really in danger of being suppressed by anyone.

Concerns about polarization and echo chambers are valid. When people talk only to others who agree, they can fail to learn, they may weaken their own influence, and they can encourage the spread of false information. However, we wouldn’t want to go too far in the opposite direction. If everyone (or a representative sample of everyone) is involved in the same discussion, then it will have a white, suburban plurality and it will marginalize ostensibly radical ideas, like defunding the police. The conversation is richer if it unfolds in many different settings with different majorities.

If you want to make policing more equitable in the short term, then you are probably better off advocating police accountability plus social services, not defunding cops. But not everyone should promote short-term ameliorative solutions. Some people should pose more fundamental questions, like “Do we need police at all?” Note, however, that if you pose this question, you should expect to hear the answer “Yes, we do” from a lot of people, not just conservative whites. And if Barack Obama tells you that the slogan polls badly–well, surely he’s entitled to that view.

Deliberative democracy was never supposed to be cool and calm, and if you can’t take the heat, stay out of the kitchen. My only desire would be for more prominent presentations of more concrete and compelling alternatives. How would a safe community without any police actually work? On the other hand, how does an accountable and equitable police force function?

It might feel like a burden to have to spell out alternatives–with tradeoffs, costs, enforcement mechanisms, and contingency plans–but that’s what self-governing people do. The great Ernesto Cortés, Jr. says:

Most people have an intuitive grasp of Lord Acton’s dictum about the tendency of power to corrupt. To avoid appearing corrupted, they shy away from power. But powerlessness also corrupts — perhaps more pervasively than power itself. So IAF leaders learn quickly that understanding politics requires understanding power.

I wonder whether some of the strongest proponents of abolishing the police are actually pessimistic about that ever happening. They may endorse the syllogism: All racist societies have unjust police; America is a racist society; therefore, America police will (always) be unjust. This logic is fundamentally disempowered. If you think that you don’t have to show what a police-free community would look like, then you are acting powerless in a corrupting way. In fact, everyone has the power to envision and present alternatives.

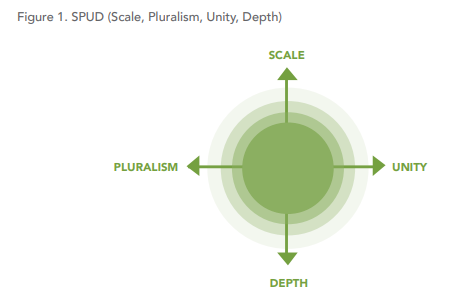

I have been advocating what I call the SPUD framework for assessing movements. In this framework, “S” stands for scale: movements should strive to recruit large numbers of individuals and groups, because they have more power if they are large. “P” stands for pluralism: movements are more effective and learn and react better if they encompass people with diverse perspectives, backgrounds, and social roles. “U” stands for unity: movements must come together behind shared demands at any given time, or else they can’t make effective demands. And “D” stands for depth: movements must help their participants to grow in knowledge, skill, experience, and wisdom.

The Movement for Black Lives has achieved almost unprecedented scale. It also demonstrates impressive depth, at least among its core members. Like all movements, it is pulled between pluralism and unity, and that tension can be fruitful. It would be a mistake to move all the way to the unity pole by excluding a robust and diverse debate about matters like criminal justice. Yet it makes sense to try to project unity and even to try to marginalize certain positions that would undermine the movement’s unity. People are always free to exit if they don’t like the mainstream of a movement; large numbers of exits serve as a form of regulation. Meanwhile, the society as a whole needs an even larger and more plural discussion of the same topics, enriched by more than one social movement.

And all of that is more or less what we are seeing. I take a generally positive view of the present debate as an example of deliberative democracy, even though, like everything human beings do, it leaves room for improvement.

See also: some remarks on Elinor Ostrom and police reform; on the phrase: Abolish the police!; “The Role of Social Movements in Fostering Sounder Public Judgment,” and “Habermas with a Whiff of Tear Gas: Nonviolent Campaigns and Deliberation in an Era of Authoritarianism“

By Andrew D. Sommers

By Andrew D. Sommers Celebrating Partnerships that Strengthen America

Celebrating Partnerships that Strengthen America